The Transformational Power of Student-centered Learning in the Classroom:

The transformational power of student-centered learning in the classroom is a beacon of hope in modern education. This pedagogical approach shifts the traditional paradigm of passive learning, making the student the central figure in their educational journey. By emphasizing active engagement, autonomy, collaboration, authentic assessment, and reflection, student-centered learning not only enhances academic outcomes but also fosters critical thinking, self-directed learning, and a lifelong love for learning. In this article, we will explore the theoretical foundations, key principles, benefits, challenges, and practical strategies of student-centered learning. By doing so, we will illuminate how this approach has the potential to revolutionize education and empower students to become confident, motivated, and resourceful learners.

Section-1: Definition of Student-Centered Learning:

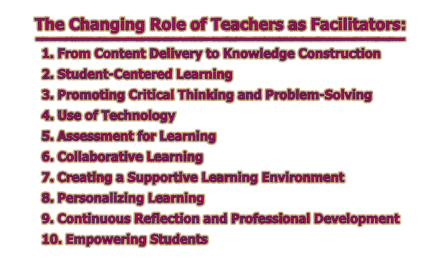

Student-centered learning, from a pedagogical standpoint, can be defined as an instructional approach that places the student at the heart of the learning process, granting them a central role in shaping their educational journey (Bransford et al., 2000). In this paradigm, the teacher transitions from the traditional role of the knowledge transmitter to that of a facilitator, guiding and supporting students as they actively engage with the learning material. Here, the emphasis is not solely on absorbing information but on fostering critical thinking, problem-solving skills, autonomy, and a sense of ownership over one’s learning (Kolb, 1984; Knowles, 1980). Student-centered learning recognizes that each learner is a unique individual with distinct needs, preferences, and strengths, thus promoting personalized learning experiences (Dewey, 1938). It also incorporates collaborative learning opportunities, where students work together, share ideas, and learn from one another, mirroring the collaborative nature of knowledge creation in the real world (Vygotsky, 1978). In essence, student-centered learning is a transformative educational approach that seeks to empower learners, preparing them not just for academic success but for a lifetime of curiosity, adaptability, and self-directed growth (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

Section-2: Theoretical Foundations of Student-Centered Learning:

Student-centered learning is grounded in several educational theories that emphasize the importance of active engagement, learner autonomy, and the social context of learning. These theories provide a theoretical framework for understanding why student-centered approaches are effective in promoting deep and meaningful learning. Some of the key theories include:

2.1 Constructivism: Constructivism, notably advanced by prominent scholars such as Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, posits that learners are not passive receivers of knowledge but active constructors of their understanding (Piaget, 1952; Vygotsky, 1978). In the context of student-centered learning, this theory underscores the idea that students actively build their knowledge by interacting with their environment and processing information based on their prior experiences and pre-existing schemas (Bransford et al., 2000).

Constructivist principles guide instructional practices in student-centered classrooms by emphasizing the importance of experiential learning and hands-on exploration. Teachers serve as facilitators, guiding students in constructing their own understanding through inquiry-based activities, problem-solving tasks, and collaborative projects (Dewey, 1938). This constructivist framework aligns seamlessly with the student-centered philosophy, as it empowers learners to take ownership of their learning by actively constructing meaning from the content.

2.2 Social Constructivism: Building upon the foundation of constructivism, social constructivism posits that learning is not only an individual endeavor but also a social process that occurs through interaction with others (Vygotsky, 1978). This theory underscores the importance of collaborative learning, where students engage in dialogue, discussions, and cooperative activities to co-construct knowledge and understanding (Bruner, 1990).

In student-centered classrooms, social constructivist principles come to life through various collaborative learning strategies (Johnson & Johnson, 1994). Group work, peer teaching, and collaborative projects provide students with opportunities to interact, share ideas, and negotiate meaning collectively. By working together, students not only deepen their understanding of the subject matter but also develop essential communication, teamwork, and problem-solving skills, fostering a holistic and socially contextualized approach to learning.

2.3 Experiential Learning: Experiential learning, as formulated by David Kolb, posits that learning is a cyclical process involving concrete experiences, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (Kolb, 1984). This theory emphasizes the value of hands-on, real-world experiences in the learning process and highlights the significance of reflection and active application of knowledge.

Student-centered learning environments often incorporate experiential elements to engage students in meaningful learning experiences. For instance, problem-solving tasks, simulations, field trips, and project-based activities encourage students to actively engage with content, reflect on their experiences, derive abstract concepts, and apply their learning to practical situations (Kolb & Kolb, 2005). Such experiential learning opportunities align closely with the principles of student-centered learning, as they promote active engagement, critical thinking, and the development of practical skills.

2.4 Self-Determination Theory: Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by Deci and Ryan (1985), posits that individuals have innate psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Within the context of student-centered learning, this theory underscores the importance of honoring students’ autonomy by allowing them to make choices about their learning, fostering competence through self-directed exploration, and promoting relatedness through collaborative activities.

Student-centered approaches align closely with SDT by prioritizing students’ autonomy and agency in their learning journeys (Reeve, 2006). In these environments, students have the freedom to choose topics, projects, or learning pathways that resonate with their interests and needs. This autonomy not only enhances motivation but also empowers students to take responsibility for their learning process, cultivating a sense of ownership and self-determination (Deci & Vallerand, 1991).

2.5 Andragogy (Adult Learning Theory): Malcolm Knowles’ theory of andragogy focuses on the unique characteristics and needs of adult learners (Knowles, 1980). While initially formulated for adult education, the principles of andragogy have been adapted for student-centered learning in various educational contexts. These principles emphasize self-directed learning, learner experience, and the application of knowledge to real-world situations.

In student-centered classrooms, andragogical principles are often applied to promote self-directed inquiry and experiential learning (Merriam, Caffarella, & Baumgartner, 2012). Students are encouraged to take an active role in shaping their learning experiences, drawing upon their prior knowledge and experiences to make meaningful connections with the content. This approach recognizes that students, regardless of age, thrive when they are actively engaged in their learning process and when the content is relevant and applicable to their lives.

Section-3: Key Principles of Student-Centered Learning:

Student-centered learning is guided by a set of core principles that distinguish it from traditional teacher-centered approaches. Principles promote active engagement, autonomy, collaboration, authentic assessment, and metacognition among students. Let’s explore the key principles of student-centered learning:

3.1 Active Engagement: Active engagement is at the core of student-centered learning, aligning with constructivist theories that emphasize learning as a dynamic, participatory process (Bransford et al., 2000). In student-centered classrooms, active engagement is fostered through a variety of pedagogical strategies, such as problem-based learning (Savery & Duffy, 1995), inquiry-based activities (Harwell & Elton, 2016), and interactive simulations (Heron & Belford, 2016). These approaches encourage students to be actively involved in constructing their own knowledge, promoting deep understanding and long-term retention of concepts (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). Through active engagement, students become more than passive recipients of information; they become active agents in their own learning journey.

3.2 Autonomy and Choice: The principle of autonomy and choice in student-centered learning draws inspiration from the theory of self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 1985). In such environments, students are given the freedom to make meaningful decisions about their learning. This could involve selecting topics of interest, determining the pace of their learning, or choosing from various learning resources and assignments (Reeve, 2006). By granting students agency in their education, educators nurture intrinsic motivation and a sense of ownership over the learning process. Autonomy not only empowers students but also acknowledges their unique learning styles and preferences (Knowles, 1980). As a result, they become more self-directed and accountable learners.

3.3 Collaboration and Peer Learning: Collaboration and peer learning are hallmarks of student-centered classrooms and align closely with the principles of social constructivism (Vygotsky, 1978). In these settings, students work together in groups or pairs, engaging in active discourse, sharing ideas, and collectively constructing knowledge (Johnson & Johnson, 1994). Collaborative activities, such as group projects, debates, and peer teaching, not only deepen students’ understanding of content but also enhance their interpersonal skills (Slavin, 1996). Through collaboration, students gain exposure to diverse perspectives, learn effective communication, and develop crucial teamwork skills, all of which are highly transferable to real-world scenarios (Dillenbourg, 1999).

3.4 Authentic Assessment: Authentic assessment in student-centered learning is firmly rooted in the belief that assessment should mirror real-world challenges and tasks (Wiggins, 1990). Instead of relying solely on traditional standardized tests, student-centered classrooms employ a diverse range of assessment methods (Moss & Brookhart, 2009). These include project-based assessments, where students demonstrate their understanding through creative projects or problem-solving tasks (Thomas, 2000); presentations that require students to communicate their knowledge effectively (Gibbs, 2010); portfolios showcasing a body of work over time (Cambridge, 2010); and performance-based assessments that evaluate practical skills and application (Darling-Hammond & Snyder, 2000). Authentic assessment not only provides a more accurate measure of students’ capabilities but also prepares them for the complexities of the real world.

3.5 Reflection and Metacognition: Reflection and metacognition are integral components of student-centered learning that align with the principles of self-regulation and self-awareness (Zimmerman, 2000). These principles encourage students to engage in critical self-reflection, assessing their own learning processes and strategies (Schön, 1987). Activities such as journaling (Moon, 1999), self-assessment (Boud & Falchikov, 1989), and peer feedback (Topping, 2003) prompt students to think deeply about their own learning experiences. Metacognitive strategies enable learners to set goals, monitor their progress, and adapt their strategies as needed (Pintrich, 2002). This reflective dimension of student-centered learning not only enhances academic performance but also cultivates lifelong learning skills, as students become more adept at evaluating and optimizing their own learning.

Section-4: Benefits of Student-Centered Learning:

Implementing student-centered learning in the classroom can lead to a wide range of benefits for both students and educators.

4.1 Enhanced Learning Outcomes: Student-centered learning consistently demonstrates its potential to enhance learning outcomes. Research indicates that when students actively engage with the content, make meaningful choices in their learning, and collaborate with peers, they tend to achieve better academic results (Bransford et al., 2000). Active participation in problem-solving, discussions, and hands-on activities promotes deeper understanding and long-term retention of knowledge (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). As a result, students are better prepared to apply what they have learned in real-world contexts, which is a hallmark of effective learning.

4.2 Improved Student Motivation: One of the key advantages of student-centered learning is its capacity to bolster student motivation. The autonomy and agency that students gain in such environments align with self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985). When students have a say in their learning and can make choices that reflect their interests and goals, they become more intrinsically motivated to excel (Reeve, 2006). This intrinsic motivation leads to increased effort, persistence, and a positive attitude toward learning. It also reduces the reliance on external rewards, such as grades, as the primary motivators for academic achievement.

4.3 Development of Critical Thinking Skills: Critical thinking skills are essential for success in the 21st century, and student-centered learning plays a pivotal role in nurturing these skills. Through problem-based learning (Savery & Duffy, 1995), inquiry-based activities (Harwell & Elton, 2016), and authentic assessments (Wiggins, 1990), students are encouraged to think critically and apply their knowledge to solve complex problems (Thomas, 2000). They learn to analyze information, synthesize ideas, and develop creative solutions. As a result, student-centered classrooms cultivate students who are adept critical thinkers, and well-equipped to face the challenges of an ever-evolving world.

4.4 Promotion of Lifelong Learning: Student-centered learning fosters a love for learning that extends beyond the classroom. When students are actively engaged in their education, see its relevance to their lives, and have the skills to direct their learning, they are more likely to become lifelong learners (Deci & Ryan, 1985). They develop the curiosity and self-directed learning skills necessary to pursue knowledge and skills independently throughout their lives. This lifelong learning mindset is a valuable asset in a world where knowledge and technology continually evolve.

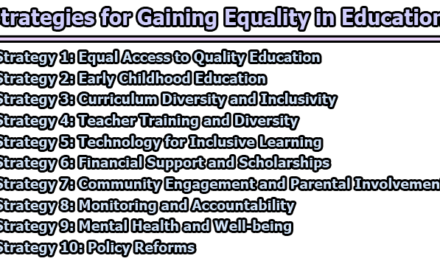

4.5 Fostering Inclusivity and Diversity: Student-centered approaches can be tailored to meet the diverse needs and backgrounds of students. By providing multiple learning pathways, resources, and opportunities for student choice (Knowles, 1980), educators can accommodate different learning styles, abilities, and interests (Tomlinson, 2003). This inclusivity promotes equity in education, ensuring that all students have access to a meaningful and personalized learning experience. In student-centered classrooms, diversity is celebrated as a source of richness and different perspectives, enriching the overall learning environment (Vygotsky, 1978).

4.6 Teacher Satisfaction: Teacher satisfaction is another positive outcome of student-centered teaching. Educators who witness their students taking ownership of their learning, making meaningful connections, and experiencing growth and development often report increased job satisfaction (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012). The sense of accomplishment derived from facilitating students’ educational journeys can lead to greater professional fulfillment. Moreover, the shift from the role of a knowledge transmitter to that of a facilitator of learning can be personally rewarding for teachers (Bransford et al., 2000).

Section-5: Challenges and Concerns in Implementing Student-Centered Learning:

While student-centered learning offers several advantages, it is not without its challenges and concerns. Educators considering the adoption of student-centered approaches should be aware of the following issues:

5.1 Resistance to Change: Resistance to change is a common challenge when transitioning from traditional teacher-centered methods to student-centered learning approaches. Educators and students alike may be comfortable with established classroom routines and roles. The shift toward student-centered learning can be perceived as a disruption (Fullan, 2007). Educators may fear losing control over the classroom, and students might resist taking on more active roles in their learning. Overcoming this resistance often requires professional development, ongoing support, and a gradual transition that allows both teachers and students to adapt (Laurillard, 2013).

5.2 Time and Resource Constraints: The implementation of student-centered learning can demand additional time and resources. Creating diverse learning materials, designing activities, and providing individualized support can be time-intensive (Barkley et al., 2014). Furthermore, schools and institutions may need to invest in training programs for educators and provide access to technology and learning resources (OECD, 2018). Addressing time and resource constraints often involves careful planning, collaboration, and creative solutions to make the best use of available resources.

5.3 Assessment Dilemmas: Traditional assessment methods may not align with the principles of student-centered learning. Student-centered approaches often involve authentic assessments, such as project-based assessments or portfolio assessments (Wiggins, 1990). Educators may grapple with the challenge of ensuring the validity and reliability of these assessments while also promoting authentic evaluation of students’ skills and knowledge (Huba & Freed, 2000). Balancing these conflicting demands can be complex but is essential for accurately gauging student achievement.

5.4 Balancing Student Autonomy and Guidance: Balancing student autonomy with the guidance provided by teachers is a delicate endeavor. While student-centered learning promotes autonomy, it does not mean abandoning students to navigate their learning journey entirely on their own. Educators must strike the right balance between offering guidance, support, and scaffolding when needed, and allowing students the freedom to make choices and take ownership of their learning (Zimmerman, 2000). Achieving this balance requires careful instructional design and continuous monitoring of students’ progress.

5.5 Addressing Diverse Learning Styles: Students come to the classroom with diverse learning styles, preferences, and needs (Tomlinson, 2003). Designing activities and resources that accommodate this diversity can be challenging. Student-centered learning aims to provide flexibility, but it may not always fully address the individual needs of every student. Educators must be attentive to these differences and be prepared to offer additional support or adaptations when necessary (Tomlinson, 2003). Personalization and differentiation strategies can help make student-centered learning more inclusive.

Section-6: Practical Strategies for Implementing Student-Centered Learning:

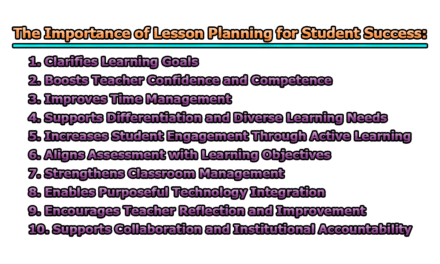

To effectively implement student-centered learning in the classroom, educators can employ a variety of practical strategies which encompass classroom management, instructional design, technology integration, assessment, and ongoing evaluation. Here are some practical approaches to consider:

6.1 Creating a Supportive Classroom Environment:

- Establish Clear Expectations: Clearly communicate your expectations for behavior, participation, and responsibilities within the student-centered classroom (Brookfield & Preskill, 2016). Setting clear guidelines helps create a structured and respectful learning environment.

- Foster a Growth Mindset: Encourage students to adopt a growth mindset, where they view challenges and mistakes as opportunities for learning and improvement (Dweck, 2006). This mindset promotes resilience and a positive attitude toward learning.

- Build a Sense of Community: Cultivate a sense of belonging and trust in the classroom by creating a positive and inclusive atmosphere (Tinto, 1997). Students should feel comfortable sharing their ideas and collaborating with their peers.

- Provide Feedback and Support: Offer constructive and timely feedback to guide students’ progress and provide support when they face challenges (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Feedback is a crucial component of the learning process.

- Encourage Self-Regulation: Teach students self-regulation skills, such as goal setting, time management, and self-assessment (Zimmerman, 2000). These skills empower students to take control of their learning.

6.2 Designing Relevant and Engaging Learning Activities:

- Start with the End in Mind: Begin by defining clear learning objectives and outcomes to guide the design of learning activities (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). This ensures that activities align with desired learning goals.

- Offer Choice and Autonomy: Provide students with choices regarding topics, projects, or learning pathways to accommodate their interests and preferences (Reeve, 2006). Choice enhances motivation and engagement.

- Incorporate Active Learning: Design activities that require students to actively engage with the content through problem-solving, discussions, debates, or hands-on experiments (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). Active learning promotes deeper understanding.

- Use Real-World Scenarios: Integrate real-world problems and scenarios into the curriculum to make learning relevant and practical (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989). Authentic contexts enhance the application of knowledge.

- Encourage Peer Collaboration: Create opportunities for students to work together, share ideas, and learn from one another through collaborative projects and group discussions (Johnson & Johnson, 1994). Peer collaboration fosters diverse perspectives and teamwork skills.

6.3 Leveraging Technology as a Tool:

- Explore Digital Resources: Utilize a wide range of digital resources, including educational websites, simulations, and multimedia materials, to enhance learning experiences (Prensky, 2001). Technology can provide access to diverse learning materials.

- Implement Blended Learning: Blend traditional classroom instruction with online or asynchronous components to provide flexibility and personalized learning opportunities (Garrison & Kanuka, 2004). Blended learning caters to different learning styles.

- Foster Digital Literacy: Teach students how to use technology responsibly and effectively for research, collaboration, and communication (Ribble & Bailey, 2007). Digital literacy is a crucial 21st-century skill.

- Use Learning Management Systems (LMS): Implement an LMS platform to facilitate communication, assignment submission, and progress tracking (Bates & Sangrà, 2011). LMS systems streamline the management of student-centered activities.

6.4 Providing Adequate Feedback and Guidance:

- Offer Formative Assessment: Use formative assessment methods, such as quizzes, surveys, and peer assessments, to provide feedback during the learning process (Black & Wiliam, 1998). Formative assessment guides students’ progress.

- Encourage Self-Assessment: Teach students to evaluate their own work and set goals for improvement (Boud & Falchikov, 1989). Self-assessment promotes metacognition and self-directed learning.

- Provide Individualized Support: Recognize that students may require different levels of support, and offer guidance accordingly (Tomlinson, 2003). Individualized support addresses diverse needs.

- Scaffold Learning Experiences: Gradually release responsibility to students as they become more proficient and confident in their abilities (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976). Scaffolding helps students transition to greater independence.

6.5 Assessing Student Learning Effectively:

- Use Diverse Assessment Methods: Employ a variety of assessment approaches, including project-based assessments, portfolios, presentations, and self-assessments, to align with student-centered learning principles (Brown & Knight, 1994). Diverse assessments capture different facets of learning.

- Align Assessments with Objectives: Ensure that assessments measure the desired learning outcomes and competencies identified in the objectives (Gronlund & Brookhart, 2009). Alignment promotes assessment validity.

- Emphasize Authentic Assessment: Design assessments that mirror real-world tasks and challenges, allowing students to demonstrate their understanding in meaningful contexts (Wiggins, 1990). Authentic assessment enhances relevance.

- Promote Peer Assessment: Encourage students to evaluate and provide feedback to their peers, fostering a sense of shared responsibility for learning (Topping, 2003). Peer assessment promotes self-reflection.

6.6 Evaluating the Impact of Student-Centered Approaches:

- Collect Feedback: Gather feedback from both students and educators to assess the effectiveness of student-centered strategies and identify areas for improvement (Barkley et al., 2014). Feedback informs instructional adjustments.

- Analyze Learning Outcomes: Compare student performance and outcomes in student-centered classrooms with those in traditional settings to gauge the impact (Prince & Felder, 2006). Outcome analysis provides evidence of effectiveness.

- Reflect and Adapt: Continuously reflect on classroom practices, make adjustments based on feedback and evidence, and refine instructional strategies (Schön, 1987). Reflective practice is essential for ongoing improvement.

Section-7: Case Studies of Successful Implementation:

To illustrate the practical application of student-centered learning, let’s explore several case studies of successful implementation in different educational settings:

7.1 Flipped Classroom Model:

Case Study: In a high school biology class, the teacher adopted the flipped classroom model to engage students in active learning. Students were assigned video lectures and readings to review before coming to class. During class, they worked in small groups to conduct experiments and engage in discussions related to the pre-assigned content. The teacher acted as a facilitator, providing guidance and answering questions as needed. This approach led to improved student engagement and deeper understanding of biology concepts (Bergmann & Sams, 2012).

Benefits:

- Increased student engagement during in-class activities.

- Opportunities for personalized learning and self-pacing.

- Enhanced teacher-student interaction during face-to-face sessions.

Challenges:

- Requires a shift in instructional planning and materials development.

- Students need access to resources outside of class, such as technology and internet connectivity (Bishop & Verleger, 2013).

7.2 Problem-Based Learning (PBL):

Case Study: At a medical school, the curriculum incorporated problem-based learning (PBL) to prepare future physicians. Students were presented with clinical cases and tasked with identifying the underlying medical issues, conducting research, and proposing treatment plans. PBL sessions encouraged active inquiry, critical thinking, and collaboration among students. Graduates of this program were found to be better at diagnosing complex cases and had strong problem-solving skills (Barrows & Tamblyn, 1980).

Benefits:

- Encourages inquiry and problem-solving skills.

- Fosters teamwork and communication skills.

- Aligns with authentic assessment methods (Savery & Duffy, 1995).

Challenges:

- Requires careful selection of relevant and engaging problems.

- May initially be challenging for students unfamiliar with self-directed learning.

7.3 Project-Based Learning (PBL):

Case Study: In an elementary school, a science teacher implemented project-based learning (PBL) to explore environmental sustainability. Students were tasked with researching local environmental issues, proposing solutions, and designing projects to address them. Projects included creating a school garden and organizing a community clean-up day. Through these projects, students not only gained a deep understanding of environmental science but also developed a sense of responsibility for their community and the environment (Thomas, 2000).

Benefits:

- Promotes deeper understanding through application.

- Encourages creativity and innovation.

- Develops time management and project management skills.

Challenges:

- Requires significant planning and coordination (Larmer & Mergendoller, 2010).

- Assessment can be complex, as it often involves multiple components (Ertmer & Simons, 2005).

7.4 Peer Teaching and Peer Assessment:

Case Study: In a college psychology course, peer teaching and peer assessment were integrated into the learning process. Students were divided into pairs and tasked with teaching a specific psychological concept to their peers. Afterward, students assessed each other’s teaching effectiveness and provided feedback. This approach not only reinforced students’ understanding of the material but also developed their communication and teaching skills. Peer assessment encouraged thoughtful reflection and improved the quality of teaching (Boud & Feletti, 1991).

Benefits:

- Encourages active engagement and deeper understanding.

- Develops communication and teaching skills.

- Promotes a sense of shared responsibility for learning (Falchikov & Goldfinch, 2000).

Challenges:

- May require training and guidance for students to provide effective feedback.

- Ensuring fairness and consistency in peer assessment can be challenging (Topping, 1998).

7.5 Inquiry-Based Learning:

Case Study: In a middle school science class, inquiry-based learning was used to explore scientific concepts. Students were encouraged to ask questions, conduct experiments, and research topics of interest. They had the freedom to choose their research questions and methods. This approach sparked curiosity and led to deeper exploration of scientific principles. Students developed research and critical thinking skills as they pursued their inquiries (Harlen & Qualter, 2004).

Benefits:

- Cultivates curiosity and a love of learning.

- Develops research and information literacy skills.

- Encourages independent thinking and problem-solving.

Challenges:

- May require guidance to help students frame research questions effectively.

- Assessment can be less structured and may involve varied outcomes (National Research Council, 2000).

In conclusion, in the quest to nurture agile and empowered learners, the transformational power of student-centered learning in the classroom stands as a beacon of hope. As we conclude this exploration, it is evident that this pedagogical shift, rooted in sound educational theories, offers a promising path forward. The benefits are substantial, from improved academic outcomes to the cultivation of critical thinking and self-motivation. Yet, it is not without its challenges, calling for the dedication and adaptability of educators. Nevertheless, the vision of education where students are not just recipients of knowledge but active participants in their learning journey is one that holds the promise of a brighter future. Embracing student-centered learning is not just an educational strategy; it is an investment in the transformation of individuals and society as a whole.

References:

- Barrows, H. S., & Tamblyn, R. M. (1980). Problem-Based Learning: An Approach to Medical Education. Springer Publishing Company.

- Barkley, E. F., Major, C. H., & Cross, K. P. (2014). Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty. Jossey-Bass.

- Bates, A. W., & Sangrà, A. (2011). Managing Technology in Higher Education: Strategies for Transforming Teaching and Learning. Jossey-Bass.

- Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2012). Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE).

- Bishop, J. L., & Verleger, M. A. (2013). The Flipped Classroom: A Survey of the Research. In ASEE National Conference Proceedings (Vol. 30, No. 9, pp. 1–18).

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards Through Classroom Assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139–148.

- Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports.

- Boud, D., & Falchikov, N. (1989). Quantitative Studies of Student Self-Assessment in Higher Education: A Critical Analysis of Findings. Higher Education, 18(5), 529–549.

- Boud, D., & Feletti, G. (1991). The Challenge of Problem-Based Learning (2nd ed.). Kogan Page.

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. National Academy Press.

- Brookfield, S. D., & Preskill, S. (2016). The Discussion Book: 50 Great Ways to Get People Talking. Jossey-Bass.

- Brown, A. L., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42.

- Brown, G., & Knight, P. (1994). Assessing Learners in Higher Education. Routledge.

- Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of Meaning. Harvard University Press.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Snyder, J. (2000). Authentic Assessment of Teaching in Context. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(5–6), 523–545.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Plenum Publishing Corporation.

- Dillenbourg, P. (1999). Collaborative Learning: Cognitive and Computational Approaches. Pergamon.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. Kappa Delta Pi.

- Ertmer, P. A., & Simons, K. D. (2005). Scaffolding Teachers’ Efforts to Implement Problem-Based Learning. International Journal of Learning, 12(4), 319–328.

- Falchikov, N., & Goldfinch, J. (2000). Student Peer Assessment in Higher Education: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Peer and Teacher Marks. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 287–322.

- Fullan, M. (2007). The New Meaning of Educational Change (4th ed.). Teachers College Press.

- Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended Learning: Uncovering Its Transformative Potential in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(2), 95–105.

- Gibbs, G. (2010). Using Assessment to Support Student Learning. Leeds Metropolitan University.

- Gronlund, N. E., & Brookhart, S. M. (2009). How to Write and Use Instructional Objectives (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Harwell, M., & Elton, L. (2016). Inquiry-Based Learning: Designing a Course and PBL (Problem-Based Learning) Scenario. Journal of STEM Education, 17(3), 15–22.

- Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School. Teachers College Press.

- Harlen, W., & Qualter, A. (2004). The Teaching of Science in Primary Schools (4th ed.). David Fulton Publishers.

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

- Huba, M. E., & Freed, J. E. (2000). Learner-Centered Assessment on College Campuses: Shifting the Focus from Teaching to Learning. Allyn & Bacon.

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1994). Learning Together and Alone: Cooperative, Competitive, and Individualistic Learning (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Prentice Hall.

- Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 193-212.

- Knowles, M. S. (1980). The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy. Cambridge Adult Education.

- Laurillard, D. (2013). Rethinking University Teaching: A Conversational Framework for the Effective Use of Learning Technologies (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Larmer, J., & Mergendoller, J. R. (2010). Project Based Learning Handbook: A Guide to Standards-Focused Project Based Learning for Middle and High School Teachers. Buck Institute for Education.

- Merriam, S. B., Caffarella, R. S., & Baumgartner, L. M. (2012). Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Moon, J. A. (1999). Reflection in Learning and Professional Development: Theory and Practice. Kogan Page.

- Moss, C. M., & Brookhart, S. M. (2009). Advancing Formative Assessment in Every Classroom: A Guide for Instructional Leaders. ASCD.

- National Research Council. (2000). Inquiry and the National Science Education Standards: A Guide for Teaching and Learning. National Academies Press.

- (2018). Schooling Redesigned: Towards Innovative Learning Systems. OECD Publishing.

- Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. International Universities Press.

- Pintrich, P. R. (2002). The Role of Metacognitive Knowledge in Learning, Teaching, and Assessing. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 219–225.

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6.

- Prince, M., & Felder, R. M. (2006). Inductive Teaching and Learning Methods: Definitions, Comparisons, and Research Bases. Journal of Engineering Education, 95(2), 123–138.

- Reeve, J. (2006). Experiencing Self-Determination in the Classroom: The Influence of Teaching Style, Student Autonomy, and Teacher’s Autonomy Support. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(2), 209–218.

- Ribble, M., & Bailey, G. D. (2007). Digital Citizenship in Schools: Nine Elements All Students Should Know. International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE).

- Savery, J. R., & Duffy, T. M. (1995). Problem-Based Learning: An Instructional Model and Its Constructivist Framework. Educational Technology, 35(5), 31–38.

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. Jossey-Bass.

- Thomas, J. W. (2000). A Review of Research on Project-Based Learning. Autodesk Foundation.

- Tinto, V. (1997). Classrooms as Communities: Exploring the Educational Character of Student Persistence. Journal of Higher Education, 68(6), 599–623.

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2003). Fulfilling the Promise of the Differentiated Classroom: Strategies and Tools for Responsive Teaching. ASCD.

- Topping, K. J. (2003). Self and Peer Assessment in School and University: Reliability, Validity, and Utility. Psychology Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wiggins, G. (1990). The Case for Authentic Assessment. ERIC Clearinghouse on Tests, Measurement, and Evaluation.

- Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining Self-Regulation: A Social Cognitive Perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College