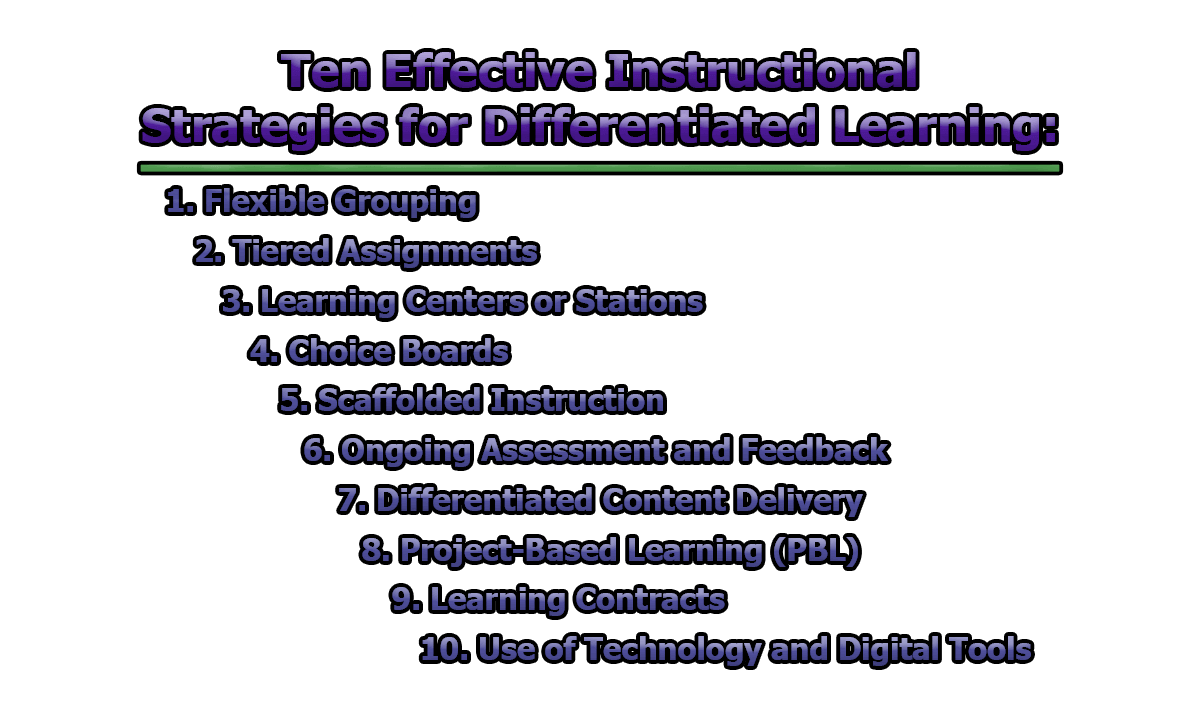

Ten Effective Instructional Strategies for Differentiated Learning:

Differentiated learning is an educational approach that tailors instruction to meet the diverse needs, skills, and interests of individual students. It recognizes that students have varying levels of readiness, learning preferences, and paces at which they absorb information. As such, educators must employ varied instructional strategies to create inclusive, equitable learning environments. Below is an exploration of ten effective instructional strategies for differentiated learning.

1. Flexible Grouping: Flexible grouping is a strategic approach to organizing students into various groups that change in composition and purpose over time. Unlike static ability grouping, where students are consistently placed based on skill level, flexible grouping allows movement based on formative assessments, interests, learning preferences, or task requirements. According to Tomlinson (2014), this approach prevents labeling and offers students multiple opportunities to work with peers of varying strengths and perspectives, which fosters collaboration and social learning.

In practice, a teacher might initially group students by reading level to work on a comprehension task. Later in the week, those same students might be grouped heterogeneously to complete a cross-disciplinary project. This variability enhances peer modeling and encourages mutual support. Gregory and Chapman (2013) emphasize that flexible grouping increases student engagement by ensuring tasks are neither too easy nor too difficult for any given group.

Moreover, research suggests that this strategy helps address both academic and social-emotional needs. Students gain confidence as they find themselves in different roles—sometimes leaders, sometimes learners—which aligns with Vygotsky’s (1978) social constructivist theory, emphasizing the value of social interaction in cognitive development.

2. Tiered Assignments: Tiered assignments are tasks designed at varying levels of complexity and abstraction to accommodate students’ diverse readiness levels, while still focusing on the same essential learning objectives. This method allows students to approach content in ways that are appropriately challenging for them, ensuring that all students are working towards mastery but through differentiated paths (Tomlinson, 2017).

For example, in a unit on persuasive writing, all students might be asked to write a persuasive piece, but the scaffolding, format, and topic difficulty may vary. One tier might use sentence starters and prompts to guide argument structure, while another group constructs arguments independently and incorporates counterarguments. A third tier might analyze multiple persuasive texts before creating an original piece supported by research. This ensures that no student is left behind or held back.

Heacox (2012) highlights that tiered assignments support higher-order thinking for advanced learners while reinforcing foundational skills for those needing more support. The key is ensuring that all tiers are respectful, equally engaging, and connected to the same learning goals.

3. Learning Centers or Stations: Learning centers are physical or virtual spaces in a classroom where students rotate among different tasks or activities, each targeting specific skills, concepts, or learning modalities. This structure is ideal for accommodating different intelligences and providing students with varied ways to engage with content (Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). The stations often include independent, collaborative, and teacher-guided tasks, allowing for real-time differentiation.

For instance, in a middle school science classroom studying plant biology, one center may involve dissecting a flower (kinesthetic), another watching a video on photosynthesis (visual), a third creating a concept map (spatial), and a fourth discussing environmental impact on plant life with the teacher (interpersonal/verbal). This variety not only meets diverse learning needs but also maintains engagement and fosters autonomy.

McCarthy (2014) argues that learning stations enhance motivation and reduce passive learning by encouraging movement and self-direction. Additionally, they enable the teacher to work closely with small groups for targeted instruction while others are meaningfully engaged.

4. Choice Boards: Choice boards are graphic organizers that offer students a range of activity options to demonstrate their understanding or engage with content in a way that suits their learning preferences. These boards typically feature a grid of tasks, with students choosing a certain number of activities, often in a tic-tac-toe or menu format. According to Wormeli (2006), offering students choices not only respects their individual learning styles but also increases ownership, motivation, and creativity.

A teacher might create a choice board for a literature unit where students select from options such as designing a book cover, composing a song related to the theme, writing a character diary, or developing a digital presentation. Each task aligns with the unit objectives but caters to different intelligences and skills (e.g., artistic, musical, linguistic, digital).]

Gregory and Chapman (2013) note that choice boards can be adapted for readiness levels by offering “mild,” “medium,” and “spicy” versions of tasks to increase or decrease cognitive demand. Importantly, all choices must be equally rigorous and tied to learning targets to maintain academic integrity while offering personalization.

5. Scaffolded Instruction: Scaffolding is a temporary support mechanism that helps learners achieve tasks they cannot complete independently but can accomplish with guidance. It draws directly from Vygotsky’s (1978) concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which identifies the difference between what a learner can do alone and what they can do with support. As learners gain skills and confidence, scaffolds are gradually removed, leading to independent mastery.

In the classroom, scaffolding may take many forms—modeling processes, using sentence frames, offering guiding questions, or breaking tasks into manageable steps. For example, in a high school history class, students writing a research paper may first analyze sample essays, then receive a graphic organizer to outline their ideas, followed by peer and teacher feedback before submitting the final draft.

Fisher and Frey (2013) emphasize that effective scaffolding involves a gradual release of responsibility—from teacher modeling to guided practice to independent work. This technique is especially effective for English language learners, students with learning disabilities, and those encountering new or complex material, as it builds confidence and capability without overwhelming them.

6. Ongoing Assessment and Feedback: Ongoing assessment, also known as formative assessment, is a continuous process of collecting evidence of student learning in order to adjust instruction in real time. Unlike summative assessments that evaluate learning at the end of a unit, formative assessments help teachers identify individual progress, strengths, and learning gaps as they occur (Black & Wiliam, 2009). This approach is foundational to differentiated instruction because it informs decisions about grouping, pacing, and task design.

In a differentiated classroom, a teacher might use exit tickets, quick quizzes, think-pair-share activities, or journal reflections to gauge understanding. For example, after a lesson on fractions, a math teacher could give a short formative quiz, then review responses to determine which students need reteaching and which are ready to move on. This ensures that instruction is responsive and data-driven.

Tomlinson (2014) argues that formative assessment is not an interruption of instruction—it is instruction. Moreover, providing timely and constructive feedback based on formative assessments helps students reflect on their learning and set goals for improvement (Brookhart, 2017). Regular feedback boosts student agency and allows for differentiated support where needed.

7. Differentiated Content Delivery: Differentiated content delivery involves presenting the same learning objectives through multiple formats, such as texts, videos, discussions, demonstrations, and digital media. This strategy respects differences in students’ learning styles, language proficiencies, and sensory preferences (Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). For example, when teaching about climate change, a teacher might offer a choice of reading an article, watching a documentary clip, or exploring an interactive online simulation.

The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework supports this approach by encouraging educators to provide multiple means of representation (CAST, 2018). This is particularly important in diverse classrooms where students may have auditory processing issues, visual impairments, or limited language proficiency. Offering varied content formats ensures accessibility and fosters equity.

Research confirms that providing diverse entry points to content not only improves comprehension but also sustains motivation, especially among students with disabilities and English language learners (Hall, Meyer, & Rose, 2012). Effective differentiation of content acknowledges that one size does not fit all in education.

8. Project-Based Learning (PBL): Project-Based Learning (PBL) is a student-centered strategy in which learners acquire knowledge and skills by working on complex, real-world problems or challenges over an extended period. PBL is inherently differentiable because it allows students to explore topics of interest, work at their own pace, and contribute according to their strengths (Larmer, Mergendoller, & Boss, 2015).

In a high school economics class, students might develop business proposals addressing local community needs, conducting research, interviewing stakeholders, and presenting solutions. Each student can assume a role suited to their skills—researcher, designer, presenter, or writer—thus promoting personalized engagement and deeper learning.

Grant and Branch (2005) found that PBL supports higher-order thinking and intrinsic motivation. The open-ended nature of projects allows teachers to differentiate expectations, resources, and levels of complexity while keeping all students anchored to the same essential question or objective. Furthermore, PBL fosters 21st-century skills like collaboration, communication, and problem-solving, which are crucial in differentiated classrooms.

9. Learning Contracts: Learning contracts are formal or informal agreements between the teacher and the student that outline individualized learning goals, processes, and deadlines. This strategy is especially effective for promoting self-directed learning, accommodating different paces, and giving students autonomy over their learning path (Tomlinson, 2017).

A middle school student who excels in science might use a learning contract to complete an independent inquiry project on renewable energy, setting their own timeline and deliverables, with teacher guidance provided through scheduled check-ins. Meanwhile, another student might use a contract to focus on improving core science vocabulary and concepts through targeted practice and assessments.

According to Knowles (1984), learning contracts are rooted in adult learning theory (andragogy), which stresses autonomy, goal-setting, and responsibility—principles that can be adapted for adolescent learners as well. Learning contracts build accountability and allow for personalized pacing, especially useful in classrooms with a wide range of abilities and motivations.

10. Use of Technology and Digital Tools: Technology is a powerful enabler of differentiated instruction. Digital tools allow for personalized learning experiences through adaptive content, interactive simulations, and real-time feedback. Platforms such as Google Classroom, Khan Academy, Nearpod, and Edmodo can offer assignments at varying levels of difficulty, provide multiple representations of content, and facilitate asynchronous learning.

For example, a language arts teacher might use a learning management system to assign different texts to students based on Lexile levels, pair them with text-to-speech features, or allow audio submissions for writing assignments. Students can move through content at their own pace and revisit challenging concepts as needed.

According to Basham, Hall, Carter, and Stahl (2016), educational technology supports Universal Design for Learning principles and enhances equity for students with disabilities or diverse learning preferences. It also empowers teachers to monitor progress and customize instruction through data analytics, making technology a cornerstone of effective differentiation.

It is apparent that differentiated instruction is essential for creating inclusive and effective learning environments that meet the needs of all students. By employing these ten strategies—flexible grouping, tiered assignments, learning centers, choice boards, scaffolding, ongoing assessment, varied content delivery, project-based learning, learning contracts, and technology integration—educators can ensure that each student receives the support and challenge they need to succeed.

References:

- Basham, J. D., Hall, T. E., Carter, R. A., Jr., & Stahl, W. M. (2016). An operationalized understanding of personalized learning. Journal of Special Education Technology, 31(3), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162643416660835

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

- Brookhart, S. M. (2017). How to give effective feedback to your students (2nd ed.). ASCD.

- (2018). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

- Fisher, D. and Frey, N. (2013). Better Learning through Structured Teaching: A Framework for the Gradual Release of Responsibility. 2nd Edition, ASCD, Alexandria.

- Grant, M. M., & Branch, R. M. (2005). Project-Based Learning In a Middle School: Tracing Abilities Through The Artifacts of Learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 38(1), 65–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2005.10782450

- Gregory, & Chapman, C. (2013). Differentiated Instructional Strategies: One Size Doesn’t Fit All (3rd ed.). Corwin.

- Hall, T. E., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. H. (2012). Universal design for learning in the classroom: Practical applications. Guilford Press.

- Heacox, D. (2012). Differentiating Instruction in the Regular Classroom. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing. (e-book) https://www.freespirit.com/files/original/Differentiating-Instruction-Regular-Classroom-preview-1.pdf

- Knowles, M. S. (1984). The adult learner: A neglected species (3rd ed.). Gulf Publishing.

- Larmer, J., Mergendoller, J. R., & Boss, S. (2015). Setting the standard for project-based learning. ASCD.

- McCarthy, J. (2014). 3 Ways to plan for diverse learners: What teachers do. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/differentiated-instruction-ways-to-plan-john-mccarthy

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). ASCD.

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2017). How to differentiate instruction in academically diverse classrooms (3rd ed.). ASCD.

- Tomlinson, C. A., & Imbeau, M. B. (2010). Leading and Managing a Differentiated Classroom. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wormeli, R. (2006). Fair isn’t always equal: Assessing & grading in the differentiated classroom. Stenhouse Publishers.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College