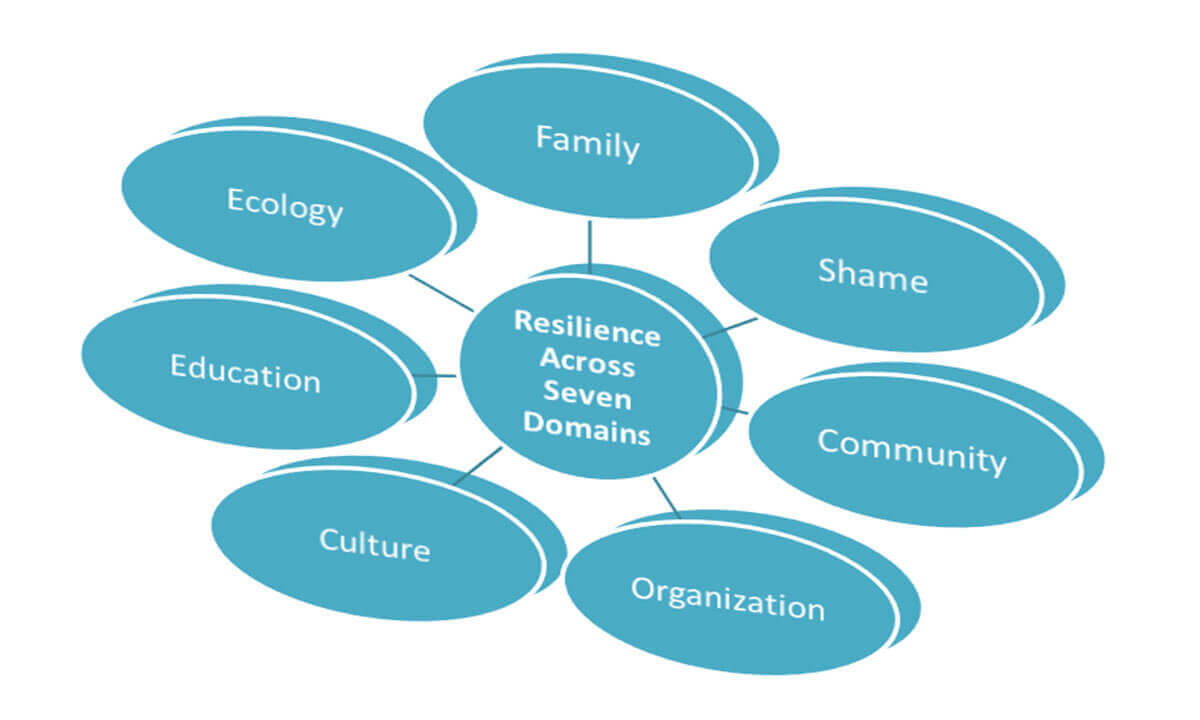

Resilience Across Seven Domains:

Resilience has emerged as one of the most significant concepts in contemporary research across psychology, sociology, education, organizational studies, and environmental science. At its essence, resilience refers to the ability to adapt, recover, and continue functioning in the face of adversity. It is often associated with an individual’s inner strength or coping mechanisms, yet resilience extends far beyond the individual level. Families, communities, organizations, cultural groups, educational systems, and even ecosystems all display unique forms of resilience that depend on their available resources, shared values, and the stressors they face. This broader perspective challenges the idea that resilience is solely a personal trait. Instead, it emphasizes resilience as a collective and systemic process. A family learning to reorganize after a crisis, a community rebuilding following a disaster, a cultural group sustaining its heritage under pressure, or an ecosystem regenerating after a disturbance are all examples of resilience manifested in distinct domains. Recognizing these different expressions of resilience helps us see it not only as a survival mechanism but also as a source of renewal, identity, and strength. In what follows, this article examines resilience across seven domains: family, shame, community, organizational, cultural, educational, and ecological. Each section explores the meaning of resilience in that context, the mechanisms that sustain it, and examples that illustrate its role in human and natural systems. The discussion concludes by drawing connections between these domains and highlighting the ways in which resilience is woven into the fabric of life itself.

- Family Resilience: Family resilience refers to the ability of family systems to adapt, connect, and recover during times of adversity. Walsh (2007) explains that this process does not simply involve avoiding conflict or minimizing hardship but relies on communication, cohesion, and shared values that allow families to reorganize when crises occur.

Families frequently encounter challenges such as illness, financial instability, migration, or the loss of loved ones. In these moments, resilience emerges through collective adjustment. When one family member loses employment, others may provide additional support, whether through financial contributions, emotional encouragement, or the assumption of new responsibilities. Such flexibility ensures that the family continues to function despite external disruption.

Communication plays a central role in family resilience. Families that speak openly about their struggles, validate each other’s emotions, and create an atmosphere of trust are better positioned to endure adversity. In addition, family rituals and shared traditions, such as regular gatherings, celebrations, or religious practices, act as stabilizing forces that reinforce unity during unstable times.

An example can be seen in families affected by chronic illness. Parents and children often adapt routines, responsibilities, and emotional roles in order to maintain stability. Instead of allowing the illness to fragment relationships, resilient families may grow stronger by cultivating empathy, patience, and deeper bonds. Research suggests that these proactive qualities of resilience enable families not only to recover from crises but also to emerge stronger and more cohesive than before.

- Shame Resilience: Shame is one of the most powerful and painful emotions, often associated with feelings of inadequacy or rejection. Shame resilience refers to the process by which individuals move through shame in ways that foster growth rather than collapse. Brown (2006) explains that shame resilience depends on self-awareness, empathy, and authentic connection with others.

The first step in building shame resilience is acknowledging the presence of shame rather than denying it. When individuals are able to recognize shame, they create space for reflection and understanding. The second step involves cultivating empathy, both toward oneself and toward others. Empathy counteracts the isolating nature of shame by fostering compassion and acceptance. Finally, connection is crucial. Shame often thrives in secrecy, but when individuals share their experiences with trusted friends, mentors, or support groups, they realize they are not alone in their struggles.

A practical illustration of shame resilience occurs in educational settings. A student who fails an exam may initially feel unworthy or inferior. Without resilience, that student might withdraw, internalize negative beliefs, or even give up on their goals. With shame resilience, however, the student interprets the failure as an opportunity to learn, seeks guidance from teachers, and maintains motivation to improve. In this way, shame becomes a stepping stone rather than a barrier.

Shame resilience highlights the emotional dimension of resilience more broadly. It demonstrates that resilience is not only about external adaptation but also about internal processes that allow individuals to confront difficult emotions with courage, empathy, and connection.

- Community Resilience: Communities, like individuals and families, face adversity that can threaten their stability and survival. Community resilience is defined by FEMA (2021) as the ability of communities to withstand disruptions, recover effectively, and maintain cohesion while preserving essential functions.

Communities face a wide range of challenges, including natural disasters, public health crises, and economic or political instability. For instance, after earthquakes or floods, entire communities often display resilience through cooperative recovery efforts. Neighbors provide shelter and resources to one another, local organizations coordinate relief, and leaders ensure that critical needs such as food, water, and medical care are met.

Community resilience depends on several interrelated factors. Social networks allow members to support one another and mobilize quickly in times of crisis. Strong leadership and inclusive governance inspire confidence and facilitate coordinated action. Access to essential resources ensures that communities can sustain themselves during disruption. Cultural identity and collective narratives provide a sense of continuity and belonging that helps people find meaning even in the midst of loss.

A global example can be seen in the COVID-19 pandemic. Across the world, communities organized mutual aid initiatives to provide food, supplies, and support for vulnerable populations. Such efforts demonstrated that resilience is not only about surviving crisis but also about strengthening relationships and building systems that will endure future challenges.

Community resilience is therefore both reactive and proactive. It involves the ability to respond to immediate crises and the foresight to prepare for future ones. In doing so, communities transform adversity into opportunities for renewal and collective strength.

- Organizational Resilience: Organizations are also subject to pressures that can disrupt their functioning. Organizational resilience is the capacity of an institution to withstand challenges, adapt quickly, and continue providing services or fulfilling its mission. Leadership, culture, and communication are central elements of this form of resilience (Walsh College, 2023).

Modern organizations face economic volatility, rapid technological changes, and global disruptions. Resilient organizations are able to adapt through innovation, reorganization, and learning. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many companies, universities, and non-profit organizations demonstrated resilience by shifting to digital platforms, adopting flexible work arrangements, and finding creative ways to serve their stakeholders.

Effective leadership is at the heart of organizational resilience. Leaders who communicate clearly and transparently build trust, while those who encourage participation and collaboration foster adaptability. Organizational culture also plays a decisive role. Workplaces that promote flexibility, innovation, and collective purpose are better equipped to navigate uncertainty. Strong communication systems ensure that all members are informed and engaged, reducing confusion and maintaining coordination during times of disruption.

Organizational resilience is not only about survival. It is also about growth and transformation. Institutions that use crises as opportunities to learn and improve are more likely to thrive in the long term. They develop new capacities, strengthen their culture, and emerge more sustainable than before.

- Cultural Resilience: Cultural resilience refers to the ability of cultural groups to sustain their identity, traditions, and values in the face of adversity. Ungar (2012) emphasizes that cultural resilience ensures continuity and meaning across generations, even when communities are subjected to displacement, discrimination, or globalization.

Cultural resilience is vividly illustrated in Indigenous communities that have preserved their languages, rituals, and histories despite centuries of colonization and oppression. These practices are not only markers of survival but also expressions of dignity and strength. They provide a sense of belonging and reinforce collective identity, which in turn sustains individuals and communities in challenging times.

Immigrant communities also display cultural resilience. When families relocate to new environments, they often face pressures to assimilate. Yet many succeed in balancing adaptation with preservation by maintaining cultural traditions while engaging with new social realities. This dual process of adaptation and continuity is a hallmark of resilience.

Cultural resilience demonstrates that resilience is not simply about recovering from crisis but also about sustaining identity and meaning. By holding onto practices, values, and narratives that affirm belonging, cultural groups ensure that adversity does not erase but instead strengthens their collective existence.

- Educational Resilience: Education is a domain where resilience is both deeply personal and socially significant. Educational resilience refers to the capacity of students to succeed academically despite exposure to significant adversity. According to Martinez and Dukes (2020), educational resilience is supported by personal motivation, strong relationships, and supportive institutional environments.

Students face challenges such as poverty, discrimination, family instability, or political unrest. Yet many demonstrate resilience by maintaining academic performance and pursuing their goals in spite of these obstacles. Relationships with teachers, mentors, and peers often provide encouragement and guidance that make resilience possible. When educators create inclusive environments, offer consistent support, and foster high expectations, they contribute directly to student resilience.

Examples of educational resilience are visible in students who continue their studies despite social disruptions. During periods of conflict or campus unrest, some students manage to excel academically, drawing upon determination and support networks. Their resilience is not simply a personal achievement but also a testament to the impact of supportive relationships and effective institutions.

Educational resilience carries implications for broader society. Students who overcome adversity often become leaders and innovators who are better prepared to navigate complex challenges in adulthood. Thus, resilience in education not only benefits individuals but also strengthens communities and societies as a whole.

- Ecological Resilience: Resilience is not confined to human systems. Ecological resilience refers to the ability of ecosystems to recover from disturbances while maintaining their essential structures and functions (Holling, 1973).

Natural systems are constantly subjected to disruptions such as climate change, pollution, and deforestation. A resilient ecosystem can adapt to such disturbances without collapsing into an entirely different state. Forests that regrow after wildfires, coral reefs that recover after bleaching, or wetlands that restore themselves after flooding are all examples of ecological resilience.

Ecological resilience is critical to human survival because it underpins essential services such as food production, water purification, and climate regulation. When ecosystems lose biodiversity or are pushed beyond their adaptive limits, their resilience diminishes, creating risks for both the environment and human communities.

Promoting ecological resilience requires conservation efforts, sustainable practices, and global cooperation. By protecting biodiversity and maintaining ecological balance, societies can ensure that natural systems continue to sustain life for future generations.

Reflection on Resilience in Action:

Resilience across these domains reveals both diversity and interconnectedness. Families demonstrate resilience through cohesion, individuals show it by navigating shame, communities express it through cooperation, organizations practice it through adaptability, cultures preserve it through identity, students embody it through academic success, and ecosystems illustrate it through regeneration.

These examples confirm that resilience is both universal and context specific. It is universal because all systems contain the potential for recovery and adaptation. It is context specific because the way resilience manifests depends on the unique challenges, values, and resources of each setting. Understanding resilience in this multidimensional way allows us to appreciate its presence in everyday life and to cultivate it more deliberately.

In conclusion, Resilience is far more than an individual trait. It is a layered, dynamic, and relational process that manifests in families, communities, organizations, cultural groups, educational systems, and ecosystems. Family resilience highlights the importance of communication and cohesion. Shame resilience emphasizes emotional awareness and empathy. Community resilience demonstrates the strength of collective action. Organizational resilience shows the value of leadership and culture in navigating uncertainty. Cultural resilience ensures continuity of identity and meaning. Educational resilience empowers students to achieve despite adversity. Ecological resilience secures the sustainability of the natural systems on which life depends.

By expanding our perspective, we begin to see resilience everywhere. It exists in households that support each other, in communities that rebuild after disaster, in organizations that transform disruption into innovation, in cultural groups that preserve meaning across generations, in students who persevere against the odds, and in ecosystems that regenerate after disturbance. Understanding resilience across domains not only deepens our appreciation of human and natural strength but also provides essential guidance for creating more sustainable, compassionate, and adaptive societies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What does resilience mean across different domains?

Resilience across domains refers to the ability to adapt, recover, and sustain functioning in the face of adversity, whether at the level of individuals, families, organizations, communities, or ecosystems. Each domain expresses resilience differently depending on its resources, values, and context.

How is family resilience different from individual resilience?

Family resilience focuses on the collective capacity of family members to support one another, adapt to changes, and maintain cohesion during times of difficulty. Individual resilience, by contrast, emphasizes personal coping strategies and internal strengths.

Why is shame resilience important for personal growth?

Shame resilience enables individuals to confront and work through feelings of shame with self-awareness, empathy, and connection. This process prevents destructive self-judgment and encourages growth, healing, and stronger relationships.

What role does community resilience play in society?

Community resilience ensures that groups of people can respond effectively to crises, such as natural disasters or social disruptions, while maintaining trust, cohesion, and essential services. Resilient communities are often better equipped to rebuild and support their members during recovery.

How do organizations build resilience?

Organizations build resilience through strong leadership, effective communication, and a culture that prioritizes adaptability and innovation. When organizations learn from challenges and integrate these lessons into future planning, they strengthen their long-term sustainability.

What are examples of cultural resilience in practice?

Examples of cultural resilience include Indigenous communities preserving languages, rituals, and traditions despite historical oppression, as well as immigrant groups maintaining cultural identity while adapting to new environments. These practices sustain identity and belonging in the face of adversity.

How can students develop educational resilience?

Students can develop educational resilience through motivation, goal setting, and strong relationships with supportive teachers, mentors, and peers. Schools that create inclusive and encouraging environments also play a critical role in helping students overcome barriers to academic success.

Why is ecological resilience essential for humanity?

Ecological resilience ensures that ecosystems can adapt and regenerate after disturbances, maintaining essential services such as food production, clean water, and climate regulation. Without ecological resilience, both environmental stability and human well-being are at risk.

Can resilience in one domain influence another?

Yes, resilience is interconnected across domains. For instance, strong family resilience can support educational resilience in children, while resilient communities can foster cultural and organizational resilience. These connections highlight the importance of viewing resilience as part of a broader system.

How can individuals contribute to resilience in their communities or organizations?

Individuals can contribute by fostering trust, maintaining open communication, supporting others, and participating in collective problem solving. Small actions, such as offering help during crises or promoting inclusive practices, can strengthen resilience at larger scales.

References:

- Brown, B. (2006). Shame resilience theory: A grounded theory study on women and shame. Families in Society, 87(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3483

- (2021). Community resilience indicator analysis. Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/community-resilience

- Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 4, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

- Martinez, R., & Dukes, R. (2020). Resilience in education: Factors supporting academic success among at-risk students. Educational Researcher, 49(4), 263–274.

- Ungar, M. (2012). Social ecologies and their contribution to resilience. In M. Ungar (Ed.), The social ecology of resilience (pp. 13–32). Springer.

- Walsh, F. (2007). Traumatic loss and major disasters: Strengthening family and community resilience. Family Process, 46(2), 207–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00205.x

- Walsh College. (2023). What is organizational resilience? https://walshcollege.edu/career-services/professional-development/what-is-organizational-resilience/

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College