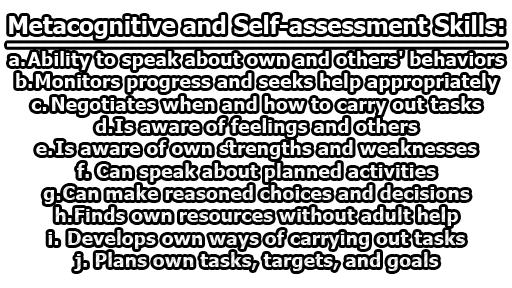

Different Aspects of Metacognitive and Self-assessment Skills:

Metacognitive and self-assessment skills are essential for success in all aspects of life, including academics, career, and personal growth. These skills involve the ability to think critically and reflect on one’s own thinking, emotions, and behaviors. Individuals who possess strong metacognitive and self-assessment skills can monitor their own progress, set goals, and make adjustments to their learning strategies as needed. Below are some examples that illustrate the different aspects of metacognitive and self-assessment skills:

a. Ability to speak about own and others’ behaviors: A student who possesses this skill can reflect on their own behavior and that of their peers in group work. They can identify instances where they or their peers were not contributing to the task and think of ways to improve.

b. Monitors progress and seeks help appropriately: A student who possesses this skill can monitor their own learning progress and identify areas where they need help. For instance, if they are struggling to understand a concept, they can seek assistance from a teacher or peer.

c. Negotiates when and how to carry out tasks: A student who possesses this skill can negotiate when and how to carry out a task. For instance, if they are part of a group project, they can discuss and agree on the best approach to take in completing the task.

d. Is aware of feelings and others: A student who possesses this skill is aware of their own emotions and that of others. They can use this awareness to manage their emotions and communicate effectively with others.

e. Is aware of own strengths and weaknesses: A student who possesses this skill is aware of their own strengths and weaknesses. For instance, they may be strong in math but weak in writing. They can use this awareness to set goals and improve in areas where they are weak.

f. Can speak about how they have done something or what they have learned: A student who possesses this skill can articulate how they have done something or what they have learned. For instance, they can explain the steps they took to solve a math problem or describe the main ideas of a book they have read.

g. Can speak about planned activities: A student who possesses this skill can articulate what they plan to do and how they plan to do it. For instance, they can explain the steps they will take to complete a project and the resources they will use.

h. Can make reasoned choices and decisions: A student who possesses this skill can weigh the pros and cons of different options and make decisions that are in their best interests. For instance, they can choose to study for a test instead of going out with friends because they understand the consequences of their actions.

i. Engages in independent cooperative activities with peers: A student who possesses this skill can work effectively with others to achieve shared goals. For instance, they can work with their peers to complete a group project, taking on different roles and responsibilities to ensure success.

j. Initiates activities: A student who possesses this skill can initiate activities on their own. For instance, they can come up with project ideas, start a club or organization, or take the lead in organizing an event. They have the motivation and drive to take action and make things happen.

k. Finds own resources without adult help: A student who possesses this skill can find their own resources without relying on adult help. For instance, they can conduct research online, reach out to experts in the field, or use their own network to find the information or support they need. They are resourceful and independent in their learning and problem-solving.

l. Develops own ways of carrying out tasks: A student who possesses this skill can develop their own ways of carrying out tasks. For instance, they can experiment with different strategies for studying or completing assignments until they find what works best for them. They are creative and flexible in their approach to learning and problem-solving.

m. Plans own tasks, targets, and goals: A student who possesses this skill can plan their own tasks, targets, and goals. For instance, they can set realistic deadlines for completing assignments, break down larger projects into smaller manageable tasks, and prioritize their workload to ensure they are making progress toward their goals. They can use self-reflection and feedback from others to adjust their goals and strategies as needed. Additionally, they can develop strategies to stay motivated and focused on their goals, such as rewarding themselves for achieving milestones along the way.

In conclusion, Metacognitive and self-assessment skills are crucial for students to succeed in academic and personal pursuits. These skills enable students to monitor their own progress, reflect on their learning, identify their strengths and weaknesses, set goals, and develop strategies to achieve those goals. Moreover, they allow students to be independent learners, take ownership of their learning, and make reasoned choices and decisions. When students possess these skills, they are better equipped to face challenges, adapt to changing circumstances, and persevere through difficulties. Overall, developing Metacognitive and self-assessment skills can lead to a more fulfilling and successful academic and personal life.

References:

- Flavell, J. H. (1976). Metacognitive aspects of problem-solving. In L. B. Resnick (Ed.), The nature of intelligence (pp. 231-235). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19(4), 460-475.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(3), 329-339.

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. Routledge.

- Pintrich, P. R. (2002). The role of metacognitive knowledge in learning, teaching, and assessing. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 219-225.

- Brown, A. L. (1978). Knowing when, where, and how to remember: A problem of metacognition. In R. Glaser (Ed.), Advances in instructional psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 77-165). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906-911.

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (1994). Self-regulation of learning and performance: Issues and educational applications. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Assistant Teacher at Zinzira Pir Mohammad Pilot School and College