Extinction in psychology refers to the gradual weakening and eventual disappearance of a conditioned response when reinforcement is no longer provided. The concept, rooted in classical and operant conditioning, has been explored by various theorists and researchers, each offering unique perspectives on its mechanisms and implications. In the rest of this article, we will explore extinction in psychology and factors that influence extinction behavior.

Extinction in Psychology:

Ivan Pavlov (1927) first described extinction in classical conditioning, observing that when a conditioned stimulus (CS) repeatedly appears without the unconditioned stimulus (US), the conditioned response (CR) diminishes. Pavlov attributed extinction to the weakening of neural connections. However, he also noted that extinction does not erase learning entirely, as spontaneous recovery can occur, wherein the conditioned response reappears after a rest period (Pavlov, 1927). This finding suggested that extinction is not unlearning but rather the formation of new inhibitory associations.

B.F. Skinner (1938) extended the concept of extinction to operant conditioning, emphasizing that behaviors decrease when reinforcement is removed. He demonstrated that when a behavior that had been previously reinforced stops receiving reinforcement, the frequency of that behavior gradually declines. Skinner also introduced the concept of “extinction bursts,” where behavior temporarily increases in intensity before diminishing. This perspective underscores the role of reinforcement schedules in determining how resistant a behavior is to extinction (Skinner, 1938).

Rescorla and Wagner (1972) developed a mathematical model to explain extinction as a reduction in associative strength between stimuli. They argued that extinction does not erase prior learning but rather updates expectations about reinforcement. According to their model, extinction occurs because the conditioned stimulus no longer predicts the unconditioned stimulus, leading to a recalibration of associative strength (Rescorla & Wagner, 1972). This model has been influential in understanding how predictions and expectations influence learning and behavior.

Bouton (2004) proposed that extinction is a form of new learning rather than the unlearning of a response. He argued that extinction is highly context-dependent, meaning that an extinguished response can return if the context changes, a phenomenon known as the renewal effect. This perspective aligns with findings that suggest memories of extinction and conditioning coexist, and that extinction does not erase previous learning but instead introduces competing memories (Bouton, 2004). This has important implications for therapeutic interventions, such as exposure therapy for anxiety disorders, where contextual factors may influence the return of fear.

Modern neuroscience research has linked extinction processes to specific brain structures, including the prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Bouton et al. (2021) found that the prefrontal cortex plays a key role in inhibiting conditioned responses during extinction, while the amygdala is involved in encoding fear-related memories. Their research suggests that extinction is an active process requiring inhibitory control rather than mere forgetting (Bouton et al., 2021). This perspective has guided treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other anxiety-related conditions by targeting brain mechanisms involved in extinction learning (Quirk & Mueller, 2008).

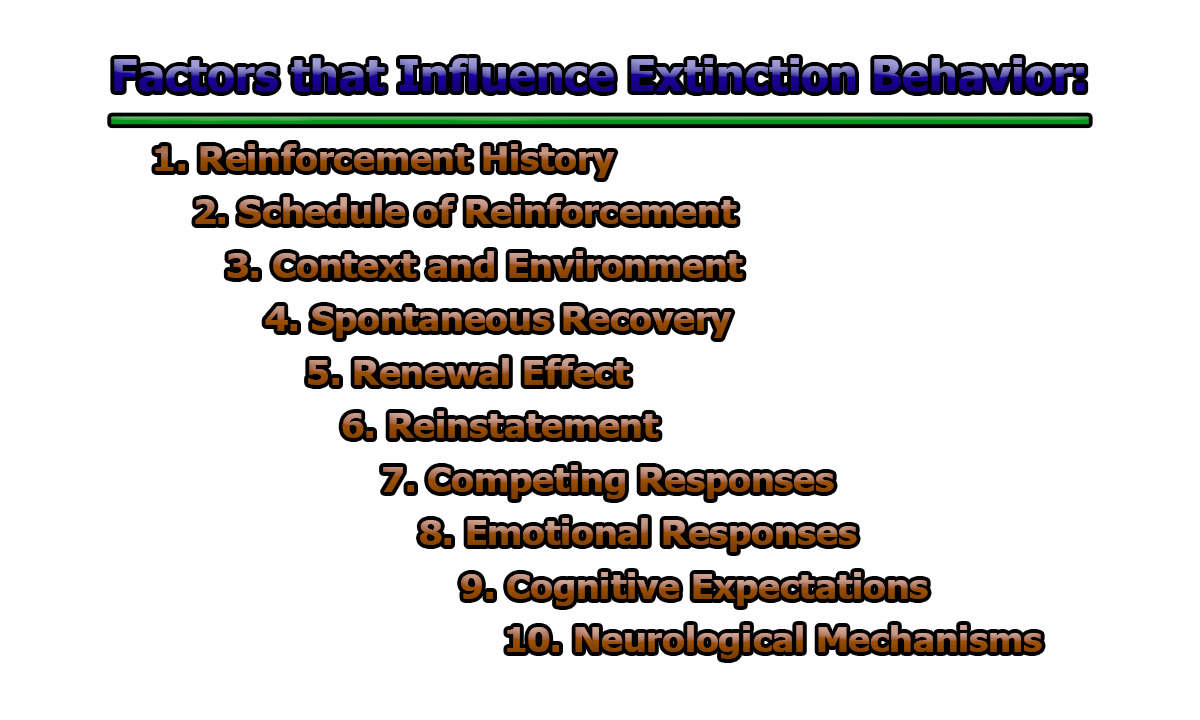

Factors that Influence Extinction Behavior:

There are several factors that influence the process of extinction in both classical and operant conditioning. Some of the essential factors are:

1. Reinforcement History: The duration and consistency of reinforcement play a crucial role in extinction. Behaviors that have been reinforced over long periods develop strong associative bonds, making them more resistant to extinction. In contrast, behaviors reinforced sporadically or for shorter durations tend to weaken more quickly when reinforcement ceases. Research by Lerman and Iwata (1996) indicates that behaviors with a strong reinforcement history require a higher number of extinction trials to diminish completely, making intervention strategies more challenging.

2. Schedule of Reinforcement: The schedule under which reinforcement was delivered significantly affects extinction. Behaviors maintained by continuous reinforcement (i.e., receiving a reward after every response) tend to extinguish more rapidly when reinforcement is removed. In contrast, behaviors reinforced on intermittent schedules—especially variable-ratio schedules (e.g., gambling, lottery participation)—are highly resistant to extinction. Nevin (1988) describes this as “behavioral momentum,” where behaviors persist despite a lack of reinforcement due to their historical reinforcement pattern. This principle is often leveraged in habit formation and addiction studies.

3. Context and Environment: Extinction is heavily influenced by environmental cues. The context in which extinction occurs may serve as a retrieval cue, affecting whether the extinct behavior re-emerges when the context changes. For example, a behavior that is extinguished in a clinical therapy setting may return when the individual returns to their home environment. Bouton (2004) emphasized that extinction is not merely unlearning but a new learning process that is context-dependent, meaning the behavior may reappear in different settings where extinction was not practiced.

4. Spontaneous Recovery: Extinction does not permanently erase learned behaviors; instead, responses may re-emerge after a time delay, a phenomenon known as spontaneous recovery. Pavlov (1927) observed that even after extinction, conditioned responses could return unexpectedly. This suggests that the original learning remains intact, but is suppressed rather than eliminated. Understanding spontaneous recovery is crucial for clinical applications, such as relapse prevention in addiction therapy, where extinguished cravings can suddenly return.

5. Renewal Effect: Closely related to context dependency, the renewal effect describes the reappearance of an extinguished behavior when an individual is placed in a different environment from where extinction training occurred. For example, a fear response that was extinguished in a therapist’s office may resurface when the individual encounters a similar stimulus in a new setting. Bouton et al. (2012) found that this effect occurs because extinction learning is tied to specific environmental cues, making generalization across different settings a challenge.

6. Reinstatement: Reinstatement refers to the reappearance of an extinguished response when the unconditioned stimulus (US) is reintroduced. Rescorla (1997) demonstrated that even a single exposure to the original reinforcement or unconditioned stimulus could bring back the conditioned response. This phenomenon is particularly relevant in cases of trauma and addiction, where a single exposure to a stressor or drug-related cue can lead to a full-blown relapse. Understanding reinstatement is key to designing interventions that minimize the risk of response recovery.

7. Competing Responses: Extinction is more effective when alternative behaviors are reinforced in place of the targeted behavior. This principle is widely used in applied behavior analysis, where differential reinforcement strategies teach individuals new behaviors that serve the same function as the extinguished behavior. Doughty et al. (2007) found that reinforcing an alternative response reduces the likelihood of the original behavior re-emerging, thereby increasing the effectiveness of extinction-based interventions.

8. Emotional Responses: The process of extinction often induces strong emotional reactions, such as frustration, aggression, or anxiety, particularly if the behavior was highly reinforced. Azrin et al. (1966) found that when reinforcement was suddenly removed, individuals and animals exhibited aggressive outbursts before extinction took full effect. This highlights the role of emotional regulation in extinction and the importance of managing frustration-related behaviors in therapeutic settings.

9. Cognitive Expectations: Expectations play a vital role in how quickly a behavior is extinguished. If an individual strongly believes that reinforcement will continue despite evidence to the contrary, extinction may be delayed. Tolman (1948) introduced the concept of cognitive maps, suggesting that organisms develop expectations about reinforcement based on past experiences. When those expectations are violated, they may resist extinction or take longer to adjust their behavior.

10. Neurological Mechanisms: Extinction is not just a behavioral process; it involves complex neural mechanisms. The prefrontal cortex is critical for inhibitory control and suppressing learned responses, while the amygdala is involved in fear-related learning and emotional processing. Bouton et al. (2021) demonstrated that extinction training leads to increased activity in the prefrontal cortex, which helps suppress the original response. Disruptions in these neural pathways, such as those seen in anxiety disorders and PTSD, can make extinction more difficult, reinforcing the need for targeted interventions like exposure therapy (Quirk & Mueller, 2008).

It is apparent that extinction is a complex process influenced by multiple psychological, cognitive, and neurological factors. While it serves as a mechanism for modifying behavior, its effectiveness depends on reinforcement history, context, emotional reactions, and the role of competing responses. Modern research emphasizes that extinction does not erase learned behaviors but instead introduces new learning that competes with prior conditioning. This insight is particularly significant for clinical applications, such as exposure therapy for anxiety disorders, addiction treatment, and behavioral modification programs. A deeper understanding of extinction and its influencing factors allows for more effective therapeutic and educational interventions, ultimately contributing to better behavioral outcomes.

References:

- Azrin, N. H., Hutchinson, R. R., & Hake, D. F. (1966). Extinction-induced aggression. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 9(3), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1966.9-191

- Bouton, M. E., Winterbauer, N. E., & Vurbic, D. (2012). Context and extinction: Mechanisms of relapse in drug self-administration. In M. Haselgrove & L. Hogarth (Eds.), Clinical applications of learning theory (pp. 103–133). Psychology Press.

- Bouton, M. E., Maren, S., & McNally, G. P. (2021). Behavioral and Neurobiological Mechanisms of Pavlovian and Instrumental Extinction Learning. Physiological Reviews, 101(2), 611–681. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00016.2020

- Bouton, M. E. (2004). Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning & Memory, 11(5), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.78804

- Doughty, A. H., da Silva, S. P., & Lattal, K. A. (2007). Differential resurgence and response elimination. Behavioural Processes, 75(2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2007.02.025

- Lerman, D. C., & Iwata, B. A. (1996). Developing a technology for the use of operant extinction in clinical settings: An examination of basic and applied research. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29(3), 345–382. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1996.29-345

- Nevin, J. A. (1988). Behavioral momentum and the partial reinforcement effect. Psychological Bulletin, 103(1), 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.1.44

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Oxford University Press.

- Quirk, G., & Mueller, D. (2008). Neural Mechanisms of Extinction Learning and Retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301555

- Rescorla, R. A. (1997). Spontaneous recovery after Pavlovian conditioning with multiple outcomes. Animal Learning & Behavior, 25(1), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03199028

- Recorla, R. A., & Wagner, A. R. (1972). A Theory of Pavlovian Conditioning: Variations in the Effectiveness of Reinforcement and Nonreinforcement. In A. H. Black, & W. F. Prokasy (Eds.), Classical Conditioning II: Current Research and Theory (pp. 64-99). New York: Appleton- Century-Crofts.

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Tolman, E. C. (1948). Cognitive maps in rats and men. Psychological Review, 55(4), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061626

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College