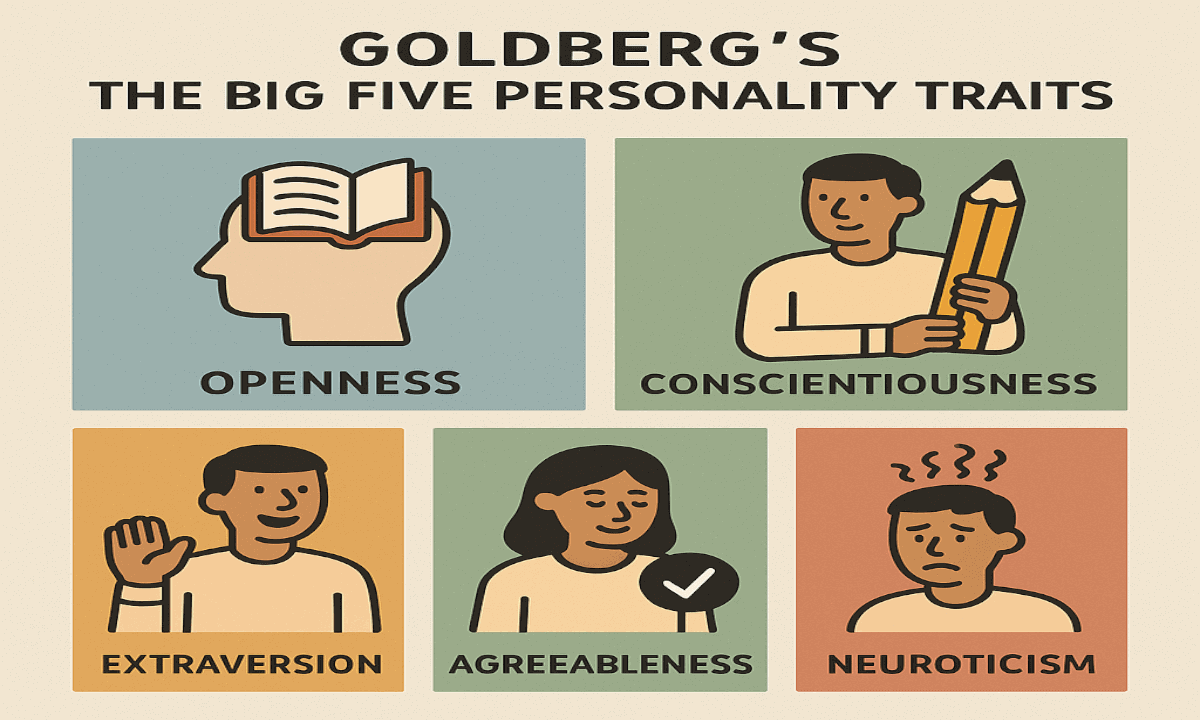

Goldberg’s the Big Five Personality Traits:

Goldberg’s the Big Five Personality Traits model offers a comprehensive framework for understanding human personality through five broad dimensions: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. These traits have been shown to predict a wide range of behaviors, emotions, and social relationships, making the model a valuable tool across fields such as therapy, coaching, human resources, and education. Despite occasional critiques, the Big Five model remains a robust and widely adopted approach in psychological research and practice.

My own fascination with the extraordinary mental and physical capacities of endurance athletes led me to consider personality as a crucial factor in their success. In particular, my PhD research identified openness to experience as a key predictor of high performance in such individuals, likely due to their willingness to embrace new challenges and experiences (Sutton, 2019). However, openness represents just one dimension of a more complex personality system. The remaining traits—conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—also play significant roles in shaping human behavior, thoughts, and interpersonal dynamics. These traits can also evolve over time, influenced by both internal dispositions and external life events (Zhang et al., 2024; Stahlmann et al., 2023). This article explores the Big Five personality trait model and examines its potential impact across various life domains.

What Are the Big Five Personality Traits?

Some researchers have attempted to explain human behavior through the lens of a single dominant trait. However, the prevailing view in psychology supports a multi-trait approach, recognizing that numerous dimensions of personality influence how individuals think, behave, and relate to others (Gross, 2020). Among the many personality taxonomies developed over time, the Big Five personality trait model stands out as the most extensively researched and widely cited (Larsen et al., 2017).

Also known as the five-factor model, the Big Five provides a robust framework for understanding personality differences across individuals and cultures. It is grounded in the belief that personality significantly shapes cognitive, emotional, and behavioral tendencies (Allen et al., 2013). The model is commonly represented by the mnemonic OCEAN, which stands for Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (Larsen et al., 2017). Early proponents of this model include Paul Costa and Robert McCrae (1976; 1992), along with Lewis Goldberg (1993), whose foundational work helped cement the Big Five as a core model in personality psychology.

The following table, inspired by their research, outlines each of the five personality traits and contrasts typical characteristics of individuals who score high versus low on each dimension (Cooper, 2021):

| Trait | High Scorers | Low Scorers |

| Openness to Experience | Emotionally sensitive and tolerant, imaginative, novelty seeking | Shallow, unsophisticated, lacking in perception |

| Conscientiousness | Motivated to achieve, self-disciplined, thinks before acting, orderly | Careless, unreliable, sloppy |

| Extraversion | Warm, seeks excitement, assertive, outgoing | Passive, reserved, introverted |

| Agreeableness | Cooperative, straightforward, modest, trusting | Cold, hostile, selfish |

| Neuroticism | Anxious, self-conscious, angry, impulsive, hostile | Calm, even-tempered |

Interestingly, high levels of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness are often associated with positive descriptions. In contrast, lower levels of neuroticism tend to be viewed favorably (Gross, 2020). Nevertheless, it is important to understand that the influence of each trait—and its perceived benefit—depends on both its intensity and the context in which it is expressed (Cooper, 2021; Gross, 2020).

How the Big Five Model Matters in Everyday Life:

Personality plays a fundamental role in shaping our experiences, decisions, and interactions—not only at the individual level but also within the groups and communities we inhabit. Understanding the Big Five personality traits provides valuable insight into why we behave the way we do and how these tendencies influence our everyday lives.

- Personality Influences Individual and Group Behavior: The Big Five personality traits significantly impact how individuals think, feel, and act, both on a personal and social level (Gross, 2020).

- Personality Differences Have Biological and Environmental Roots: Studies of identical twins suggest that up to 50% of individual differences in the Big Five traits are heritable, while the remaining variation is shaped by environmental factors, including upbringing and life experiences (Workman & Reader, 2015).

- Personality Traits May Have Evolutionary Advantages: Evolutionary psychologists argue that personality diversity supported human survival. For example, extraverted individuals may have been more inclined to explore and find resources during times of scarcity, while conscientious individuals may have been better at managing resources during abundance (Buss, 2009; Buss, 2016; Workman & Reader, 2015).

- Personality Traits Shape Daily Decisions and Long-Term Outcomes: Traits such as openness influence creativity and willingness to try new experiences; conscientiousness supports discipline and goal-setting; extraversion affects sociability and assertiveness; agreeableness impacts relationship building; and neuroticism relates to emotional stability (Cooper, 2021).

- High Neuroticism May Be Linked to Mental Health Risks: Individuals who score high in neuroticism are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and emotional instability, whereas lower neuroticism is associated with emotional resilience (Cooper, 2021).

- Personality Affects Major Life Choices: The Big Five traits influence career selection, relationship quality, health behaviors, and even financial decision-making (Gross, 2020; Cooper, 2021).

- Emotional Intelligence Complements Personality Traits: According to Goleman (2006), understanding one’s emotions and those of others enhances self-motivation, resilience, impulse control, and social functioning—areas that go beyond static personality traits and enable adaptive behavior.

- Situational Contexts Modify Trait Expression: The effectiveness of any personality trait depends on its intensity and the situation. For instance, high conscientiousness is generally beneficial, but in overly rigid contexts it may hinder flexibility (Cooper, 2021; Gross, 2020).

The Big Five model offers a powerful framework for understanding the diverse ways in which personality traits manifest and affect our lives. Combined with emotional intelligence, this understanding empowers us to make informed choices, enhance our well-being, and build more effective personal and professional relationships.

Big Five Personality Tests:

Over the years, psychologists and researchers have developed various tools to measure the five dimensions of the Big Five personality framework. Among the most recognized and empirically validated tools are the Big Five Inventory (BFI) and the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R). However, other notable instruments, such as Goldberg’s Adjective Scale, also contribute meaningfully to personality assessment.

1. Big Five Inventory (BFI): Developed by Lewis Goldberg in 1993, the Big Five Inventory is one of the most widely used tools for assessing the Big Five traits: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (Goldberg, 1993). The BFI consists of 44 statements that respondents rate on a Likert scale, typically ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. It evaluates the five traits across 30 underlying facets (six for each trait), providing a nuanced profile of personality.

Facets Measured in the BFI:

- Extraversion vs. Introversion:

- Gregariousness (sociability)

- Assertiveness

- Activity level

- Excitement-seeking

- Positive emotions

- Warmth

- Agreeableness vs. Antagonism:

- Trust

- Straightforwardness

- Altruism

- Compliance

- Modesty

- Tender-mindedness

- Conscientiousness vs. Impulsiveness (or Lack of Direction):

- Competence

- Orderliness

- Dutifulness

- Achievement-striving

- Self-discipline

- Deliberation

- Neuroticism vs. Emotional Stability:

- Anxiety

- Angry hostility

- Depression

- Self-consciousness

- Impulsiveness

- Vulnerability

- Openness to Experience vs. Closedness to Experience:

- Ideas (abstract thinking)

- Fantasy (imagination)

- Aesthetics (appreciation of art and beauty)

- Actions (adventurousness)

- Feelings (emotional awareness)

- Values (open-mindedness)

The BFI remains widely used in academic and applied psychology due to its brevity, reliability, and comprehensiveness.

2. NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R): Originally created by Paul Costa Jr. and Robert McCrae in the 1970s, the NEO Personality Inventory began by measuring just three of the five personality traits—neuroticism, extraversion, and openness. Later revisions, most notably in 1992, expanded the inventory to include all five traits, thus aligning it with the full Big Five framework (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Gross, 2020). Subsequent updates in 1990, 2005, and 2010 continued to refine the inventory for research and clinical use.

The most comprehensive version of the test, the NEO PI-R, consists of 240 items and evaluates the same 30 personality facets as the BFI, but in significantly more detail. It is ideal for:

- Clinical assessments

- Psychological research

- Career and counseling settings

For those seeking a more concise measure, the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) offers a 60-item version, focusing on the five broad domains rather than their sub-facets.

Importantly, the NEO PI-R:

- Can be self-administered

- Requires only a sixth-grade reading level

- Does not require a trained professional for scoring

3. Goldberg’s Adjective Scale: Another notable assessment tool is Goldberg’s Adjective Scale, which offers both a 50-item and a shorter 25-item version. Unlike the BFI and NEO PI-R, which use statements or full sentences, this test uses single adjectives commonly associated with personality traits.

Respondents rate how accurately each adjective describes them on a scale from 0 (Not at all accurate) to 4 (Extremely accurate). This tool is especially useful in survey-based and time-constrained contexts.

Sample adjectives include:

- Negative traits: Sluggish, Hostile, Sad, Careless, Shy, Nervous

- Positive traits: Happy, Kind, Lively, Assertive

- Neutral or context-dependent: Touchy, Introverted

This adjective-based approach provides a quick, intuitive measure of personality that is still grounded in the Big Five model.

The Big Five personality framework is supported by several well-developed and validated tests, each suited to different needs and contexts. The Big Five Inventory and NEO PI-R offer in-depth, research-based insights, while Goldberg’s Adjective Scale presents a simpler, adjective-based alternative. Whether for academic, clinical, or personal development purposes, these tools contribute significantly to our understanding and application of personality psychology.

Dissecting the Research & Validity of the Five-Factor Model:

The Big Five personality trait model—comprising openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—has become a cornerstone of contemporary personality psychology. Its prominence stems from a robust body of research, repeated validation across cultures and languages, and continued utility in both academic and applied settings.

Origins and Development: The roots of the Five-Factor Model can be traced to the lexical hypothesis, which posits that key personality characteristics are encoded in language. Based on this idea, Lewis Goldberg (1993) selected 1,710 descriptive trait terms derived from an earlier study and had college students rate themselves on each. The analysis of these ratings helped isolate consistent patterns that clustered into five broad personality domains.

In parallel, Paul Costa and Robert McCrae (1976) took a different approach by analyzing intercorrelations among existing personality inventories. Their work aimed to unify disparate psychological trait models. Through extensive factor analysis, they converged on the same five core traits, which were later confirmed through additional psychometric testing across diverse populations and languages (Larsen et al., 2017).

Empirical Support and Replication: Despite early criticisms that the selection of five traits seemed arbitrary, the model has since been extensively replicated using different populations and methodologies over several decades. Studies using both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses consistently arrive at the five core dimensions, even when carried out in non-Western cultures, supporting the model’s cross-cultural validity (Larsen et al., 2017).

The five-factor structure has also been found to be relatively stable over time, particularly in adulthood, although the expression of traits may vary depending on environmental factors and life stages.

Methods of Assessment: To establish its reliability, researchers employed two main self-rating techniques:

- Single-word adjectives: Participants scored themselves on traits like “organized,” “warm,” or “imaginative”—a simple but powerful approach based on lexical descriptors.

- Full-sentence statements: Individuals responded to items such as “My life is fast paced” or “I often feel anxious”, allowing for more nuanced reflection and contextual interpretation.

Both methods showed strong consistency in identifying the five major traits across different instruments, reinforcing the robustness of the model.

Facets (The Nuanced Layers): Beyond the five main dimensions, the Five-Factor Model incorporates facets or sub-traits that provide finer-grained insights into individual differences. For example:

- Openness includes facets like imagination, aesthetics, and openness to new values.

- Conscientiousness includes order, self-discipline, and achievement striving.

- Extraversion comprises assertiveness, sociability, and excitement-seeking.

- Agreeableness reflects trust, altruism, and compliance.

- Neuroticism covers anxiety, hostility, and vulnerability.

These facets allow researchers and practitioners to distinguish between individuals who may share a high-level trait score but differ in the specific ways that trait manifests.

While no personality model is without limitations, the Five-Factor Model continues to stand on a strong foundation of empirical research and widespread validation. From Goldberg’s lexical analysis to Costa and McCrae’s psychometric refinements, the Big Five traits represent a scientifically supported framework that is both practically useful and theoretically sound.

Applying the OCEAN Personality Traits in Professional Contexts:

While the Big Five personality trait model—often abbreviated as OCEAN for Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism—provides rich insights into human behavior at an individual level, it also serves as a powerful tool in professional environments. Professionals across various domains, including therapy, coaching, human resources, and education, have increasingly adopted this model to inform practices and improve outcomes.

A. Therapy and Clinical Psychology: Understanding a client’s personality profile can be foundational in building a strong therapeutic alliance. In clinical settings, knowledge of where a client falls within each trait spectrum enables therapists to tailor therapeutic approaches to the client’s disposition. For example, individuals high in neuroticism may be more prone to emotional instability and benefit from interventions focused on emotional regulation, while those low in openness might need more structured approaches to explore alternative thought patterns or behaviors.

According to Dobson and Dozois (2021), therapists who utilize personality profiles in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can foster deeper empathy and alignment with client needs, thereby improving client engagement and enhancing treatment outcomes. For instance, therapy with a highly conscientious client may focus on reducing perfectionistic tendencies, while interventions for those low in agreeableness might address interpersonal conflicts or empathy deficits.

B. Coaching and Personal Development: In coaching contexts—whether executive, life, or performance coaching—awareness of personality traits allows for the development of individualized growth plans. Coaches can use the Big Five framework to identify personality strengths and potential growth areas that influence a client’s leadership style, work habits, communication patterns, and emotional resilience.

Greenberg (2016) emphasizes that each of the five traits can serve as a developmental asset. For example:

- High conscientiousness can be cultivated to enhance goal-setting and productivity.

- Elevated extraversion may support networking, leadership, and public-facing roles.

- Low agreeableness, while sometimes challenging, can be addressed through activities designed to improve empathy, negotiation skills, and emotional intelligence.

In this way, coaching becomes not just reactive but proactive, helping individuals leverage their personalities for improved performance and self-awareness.

C. Human Resources and Organizational Psychology: The Big Five model is widely applied in human resources (HR), particularly in areas such as personnel selection, leadership development, and team building. Pre-employment personality assessments based on the OCEAN traits help HR professionals align candidates with specific job requirements, organizational culture, and team dynamics.

For instance, roles requiring structure and attention to detail may favor candidates high in conscientiousness, while extraversion might be beneficial for sales or client-facing roles. High agreeableness can be crucial in roles involving teamwork, while low neuroticism is often associated with emotional stability and resilience under pressure.

According to Jain et al. (2024), the use of personality assessments in recruitment can increase employee-job fit, improve job satisfaction, reduce turnover, and enhance organizational performance. Furthermore, understanding team members’ personality profiles can facilitate conflict resolution, collaboration, and role delegation.

D. Education and Learning Environments: In educational settings, personality traits can significantly influence both teaching styles and learning outcomes. Educators who understand their students’ personality profiles can adopt differentiated instruction strategies that align with their learners’ preferences and cognitive styles.

For instance, students high in openness to experience may thrive in exploratory, discussion-based environments, whereas conscientious learners may prefer structured syllabi and clear objectives. Teachers may need to provide additional motivation and scaffolding for students low in extraversion or high in neuroticism, who may struggle with participation or stress management.

Poropat (2009) found a strong association between conscientiousness and academic performance, suggesting that this trait is a better predictor of academic success than traditional intelligence measures. Similarly, Çağataylı and Çelebi (2021) highlight the growing interest in how personality traits affect learning outcomes, motivation, and self-regulation. This research supports efforts to personalize pedagogy and implement adaptive learning systems that cater to diverse learner profiles.

The application of the Big Five personality traits across professional fields underscores their practical relevance and versatility. From improving therapeutic rapport and coaching effectiveness to optimizing talent management and enhancing educational experiences, the OCEAN model provides a scientifically grounded framework for understanding and supporting human behavior in complex real-world settings.

Common Challenges and Critiques of the Big Five Personality Trait Model:

While the Big Five personality trait model—also known as the Five-Factor Model (FFM)—has achieved global recognition and widespread application in psychology, education, human resources, and clinical settings, it is not without its limitations. Scholars and practitioners have raised several significant critiques concerning the model’s scope, applicability, theoretical foundations, and methodological robustness.

i. Limited Scope (Does Not Fully Capture Human Personality): One of the primary criticisms is that the Big Five model does not encompass the entire complexity of human personality. It describes broad, stable traits but neglects other essential characteristics that many psychologists consider integral to personality. For instance, honesty and humility, which are strongly linked to prosocial behavior and moral reasoning, are notably absent from the Big Five.

As a result, an alternative model—the HEXACO model—was developed. This six-factor model includes the additional domain of Honesty-Humility, offering a potentially more comprehensive perspective (Cooper, 2021). Advocates argue that this sixth trait better captures ethical behavior, sincerity, and fairness, which are not explicitly addressed in the traditional Big Five framework.

ii. Cultural Limitations (Questionable Cross-Cultural Validity): Another key critique is the question of generalizability across different cultures. Although the Big Five traits have been validated in various countries and languages, some studies suggest that the importance or expression of specific traits may differ significantly across cultural contexts.

For instance, the trait of extraversion may carry different social implications in collectivist cultures (where group harmony is prioritized) compared to individualist cultures (which value assertiveness and independence). Similarly, neuroticism may manifest differently in societies that vary in their emotional expression norms (Cooper, 2021; Gross, 2020).

While proponents of the model argue that the Big Five are universal at a structural level, critics point out that the interpretation, social value, and behavioral expression of these traits can vary widely. This raises concerns about the cultural fairness of personality assessments based on the model (Larsen et al., 2017).

iii. Fixed vs. Dynamic (The Model Overemphasizes Stability): Although the Big Five traits are often described as relatively stable over time, critics argue that the model contributes to a misconception that personality is fixed. In reality, personality is dynamic and malleable, especially across the lifespan. Major life events such as trauma, illness, or personal growth experiences can significantly influence a person’s personality traits.

Recent longitudinal research supports the idea that personality can and does change. For instance, individuals often become more agreeable and conscientious and less neurotic with age (Thornton et al., 2023). Moreover, personality can shift in response to deliberate efforts, such as those made in therapy, or due to environmental factors like social roles and responsibilities.

Therefore, critics urge caution when using the model to make long-term predictions or assumptions about an individual’s behavior based solely on trait scores.

iv. Descriptive, Not Explanatory (Lacks Underlying Psychological Mechanisms): The Big Five model is often described as descriptive rather than explanatory. That is, while it categorizes observable patterns of behavior, it does not explain why individuals develop certain traits or how these traits interact with cognitive and emotional processes.

This limitation has implications for both theory and practice. For instance, knowing that a person is low in conscientiousness may help predict certain behaviors (e.g., procrastination), but it does not explain what caused that trait to develop or how it might be altered through intervention. As such, the model offers limited insight into the psychological mechanisms that drive personality development and change (Larsen et al., 2017).

v. Reliance on Self-Report Measures (Subject to Bias and Distortion): The majority of Big Five assessments rely on self-report questionnaires, which introduce several potential sources of error. Individuals may intentionally or unintentionally misrepresent themselves due to social desirability bias, lack of self-awareness, or mood-related distortions at the time of assessment.

For example:

- A job applicant may exaggerate their conscientiousness to appear more employable.

- An individual suffering from depression might underreport their extraversion or emotional stability.

Such limitations raise concerns about the validity and reliability of the results, especially when used in high-stakes contexts such as recruitment or diagnosis. While methods such as peer reports and behavioral assessments can complement self-report tools, these are less commonly used due to practical constraints (Gross, 2020; Cooper, 2021).

While the Big Five personality trait model remains one of the most influential frameworks in psychology, it is important to recognize and critically assess its limitations. Issues related to trait coverage, cultural sensitivity, assumed stability, lack of explanatory depth, and methodological weaknesses suggest the need for cautious application and ongoing refinement. Researchers and practitioners alike are encouraged to consider complementary models and multi-method approaches to gain a more nuanced and complete understanding of personality.

Helpful Assessments for Practitioners:

While the Big Five Personality Trait Model remains a foundational framework in understanding core aspects of human behavior and personality, practitioners often benefit from incorporating additional tools and assessments that provide deeper insights into specific emotional, cognitive, and behavioral domains. These tools can be especially helpful for tailoring interventions, promoting self-awareness, and facilitating client growth across various age groups and therapeutic goals.

1. Understanding Self-Confidence: This assessment is particularly useful for teens, adolescents, and adults who are struggling with self-image and identity issues. It helps individuals:

- Explore the roots of their self-doubt.

- Evaluate their current levels of self-belief.

- Identify situations where their confidence tends to rise or fall.

By encouraging introspection, the tool assists in recognizing internal strengths and external barriers that impact self-confidence. Practitioners can use the results to develop personalized strategies for building resilience, reinforcing positive self-talk, and setting achievable goals.

2. Things I Like About Me: A simple yet impactful tool, this worksheet encourages individuals to identify and articulate their positive qualities, which is especially helpful for:

- Clients with low self-worth.

- Children and adolescents who may struggle with identity formation.

- Individuals experiencing depression or negative self-perceptions.

By shifting focus from deficits to strengths, this activity supports the development of a more balanced and compassionate self-view. It can also serve as a conversation starter in therapy sessions and reinforce positive thinking habits.

3. The Self-Esteem Checkup: This assessment targets the concept of self-esteem, defined as one’s perception of their inherent worth and capabilities. It provides insights into:

- How individuals view themselves in social, emotional, and academic contexts.

- The degree of self-love, self-respect, and internal validation they possess.

- Areas of strength versus areas requiring support.

Therapists can use the results to design interventions that promote empowerment, reduce self-criticism, and develop a healthier internal dialogue. The checkup is also useful in tracking changes in self-esteem over time as therapy progresses.

4. Anxiety Record: An anxiety record is a structured journaling tool that allows clients to capture instances of anxiety by recording:

- The triggering situation or thought.

- The physical and emotional reactions experienced.

- The coping strategies used (or lack thereof).

- The aftermath or resolution of the episode.

This tool is especially beneficial for clients dealing with generalized anxiety, social anxiety, or panic disorders. It promotes awareness of anxiety patterns, identifies common triggers, and supports the implementation of CBT-based coping techniques, such as cognitive restructuring or grounding.

5. Self-Consciousness Scale: This self-assessment tool helps clients reflect on their level of self-awareness and social sensitivity. It typically assesses:

- Public self-consciousness (how one believes others perceive them).

- Private self-consciousness (internal reflection on one’s thoughts and emotions).

- Social anxiety or discomfort in group settings.

Understanding where a client falls on this scale allows practitioners to:

- Address shyness, fear of judgment, or performance anxiety.

- Promote assertiveness training or exposure-based therapies.

- Help clients build self-compassion and realistic social perspectives.

6. Labeling Your Feelings: Especially useful for children and adolescents, this exercise encourages clients to:

- Develop emotional vocabulary.

- Accurately label and name feelings they might not fully understand.

- Reflect on why they are feeling a certain way and what might have triggered it.

This activity is fundamental in emotional intelligence development and is often used in play therapy, art therapy, and trauma-informed practices. It fosters emotional literacy, improves communication, and strengthens interpersonal relationships.

7. Basic Needs Satisfaction in General Scale: Rooted in Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), this scale assesses the extent to which individuals feel their basic psychological needs are being met across three dimensions:

- Autonomy (the need to feel in control of one’s actions),

- Competence (feeling capable and effective), and

- Relatedness (feeling connected and valued by others).

Practitioners use this assessment to:

- Understand client motivation and well-being.

- Identify unmet needs contributing to emotional distress, disengagement, or burnout.

- Design interventions that aim to restore balance and psychological fulfillment in daily life.

Subsequently, while the Big Five model offers a robust structure for understanding personality traits, these complementary assessments allow practitioners to explore more nuanced emotional and psychological dimensions. They can be especially useful in:

- Therapy (for emotional insight and trauma processing),

- Coaching (for goal-setting and personal development),

- Education (to support social-emotional learning),

- Youth work and parenting (for promoting emotional intelligence in children).

Using a multi-method, holistic approach enhances the effectiveness of interventions and ensures that clients are understood and supported as whole individuals, not just through a trait-based lens.

Finally, we can say that throughout history, humanity has been driven by the fundamental question: Who am I? In the modern era, psychological science has brought us closer than ever to understanding the complex interplay of traits that shape who we are as individuals. Among the various models developed to explain human personality, the Big Five Personality Trait Model has emerged as one of the most researched, robust, and widely accepted frameworks.

Pioneered by figures such as Paul Costa Jr. and Robert McCrae (1976) and supported by decades of empirical research, the Big Five—Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism—provide a multidimensional understanding of individual differences that is both practical and theoretically grounded (Cooper, 2021). Often remembered through the acronym OCEAN, this model offers valuable insights into how personality influences human thoughts, emotions, and behavior across diverse life domains, including education, therapy, workplace dynamics, and personal development (Gross, 2020; Larsen et al., 2017).

For professionals dedicated to enhancing individual and collective wellbeing—whether in therapeutic, educational, organizational, or coaching contexts—the Big Five model serves as a vital tool. Familiarity with its dimensions and associated assessments enables practitioners to tailor interventions, foster self-awareness, and ultimately support more meaningful personal and professional growth.

In an ever-evolving world, a deeper understanding of personality is not merely academic—it is essential. The Big Five model continues to offer a powerful lens through which we can understand ourselves and others more fully, enhancing both our relationships and the outcomes of the work we do.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What are the Big Five personality traits?

The Big Five personality traits—often remembered by the acronym OCEAN—are five broad dimensions used to describe human personality. They include:

- Openness to Experience: Reflects imagination, creativity, curiosity, and openness to new ideas and experiences. People high in openness tend to enjoy art, adventure, and new experiences, while those low in openness may prefer routine and familiarity.

- Conscientiousness: Represents a person’s level of organization, responsibility, and dependability. Highly conscientious individuals are disciplined, goal-oriented, and detail-focused, whereas those lower in this trait may be more spontaneous or careless.

- Extraversion: Relates to how outgoing and social a person is. Extraverts are energetic, talkative, and assertive. They enjoy being around people and often seek excitement. Introverts, by contrast, tend to be more reserved, independent, and prefer solitude.

- Agreeableness: Refers to how cooperative, kind, and compassionate someone is toward others. People high in agreeableness are typically empathetic and trustworthy, while those lower on this trait may be more skeptical, competitive, or challenging.

- Neuroticism: Measures emotional stability and how prone someone is to negative emotions. High neuroticism can mean a person experiences anxiety, mood swings, or irritability, while low neuroticism indicates calmness and emotional resilience.

Where did the Big Five model come from?

The model was developed through the work of several researchers, notably Paul Costa and Robert McCrae (1976; 1992), and Lewis Goldberg (1993), who helped establish and refine the five-factor structure through lexical and statistical analysis.

How are the Big Five traits measured?

Personality traits in the Big Five model are commonly measured through self-report questionnaires. These questionnaires typically ask individuals to rate how much they agree or disagree with various statements or how well certain adjectives describe them. Based on responses, scores are calculated for each of the five traits, giving a profile of the person’s personality. Some assessments are detailed and include many items, while others are shorter and used for quick insights.

Can personality traits change over time?

Yes, personality is not entirely fixed. While many aspects remain stable, especially in adulthood, research shows that personality traits can and do shift over time. Life experiences, major life changes, personal growth efforts, and aging can all influence how traits develop. For example, people often become more conscientious and emotionally stable as they grow older.

Is the Big Five model used around the world?

The Big Five has been studied across many countries and cultures and is widely recognized globally. However, how traits are expressed and interpreted can vary between cultures. Some researchers argue that additional traits might be needed to fully capture personality in certain cultural settings, but the Big Five remains one of the most universal models used today.

How is the Big Five model used in real life?

The model is applied in many practical settings, including:

- Mental health and therapy: Therapists use personality profiles to tailor their approach to individual clients.

- Career coaching and development: Coaches help clients understand their strengths and areas for improvement.

- Hiring and human resources: Employers use personality assessments to match people to roles where they are most likely to succeed.

- Education: Teachers can adapt their teaching strategies based on students’ personality-driven learning preferences.

Understanding someone’s personality can help improve communication, teamwork, and personal relationships.

Is the Big Five the only way to understand personality?

No. While it is one of the most researched and reliable models, there are other personality frameworks as well. These include the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the HEXACO model, and trait theories like Eysenck’s three-factor model. Each has different applications, and some are more popular in specific settings like business or counseling.

How accurate are Big Five personality tests?

Big Five tests are considered scientifically robust, especially when using validated and well-developed questionnaires. However, like all self-report assessments, their accuracy depends on the honesty and self-awareness of the person taking the test. People may unintentionally overestimate or underestimate certain traits, or their responses may be influenced by how they want to be perceived.

References:

- Allen, M. S., Greenlees, I., & Jones, M. V. (2013). Personality in sport: A comprehensive review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 184–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2013.769614

- Buss, D. M. (2009). How can evolutionary psychology successfully explain personality and individual differences? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(4), 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01138.x

- Buss, D. M. (2016). Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Çağataylı, M., & Çelebi, E. (2021). Estimating academic success in higher education using big five personality traits, a machine learning approach. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, 47(2), 1289–1298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-021-05873-4

- Cooper, C. (2021). Individual differences and personality. Routledge.

- Costa Jr, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1976). Age differences in personality structure: A cluster analytic approach. Journal of Gerontology, 31(5), 564–570. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/31.5.564

- Costa Jr, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI): Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Costa Jr, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1995). Domains and facets: Hierarchical personality assessment using the Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 64(1), 21–50. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_2

- Dobson, K. S., & Dozois, D. J. (2021). Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies. The Guilford Press.

- Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. The American Psychologist, 48(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26

- Goleman, D. (2006). Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books.

- Greenberg, L. S. (2016). Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings. American Psychological Association.

- Gross, R. D. (2020). Psychology: The science of mind and behaviour. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Jain, D., Sangwan, S. R., & Kumar, A. (2024). Hyper-personalized employment in urban hubs: Multimodal fusion architectures for personality-based job matching. Neural Computing and Applications. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-024-10587-3

- Larsen, R., Buss, D., Wismeijer, A., & Song, J. (2017). Personality psychology: Domains of knowledge about human nature. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Poropat, A. E. (2009). A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014996

- Stahlmann, A. G., Hopwood, C. J., & Bleidorn, W. (2023). Big five personality traits predict small but robust differences in civic engagement. Journal of Personality, 92(2), 480–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12838

- Sutton, J. (2019). Psychological and physiological factors that affect success in ultra-marathoners (Doctoral thesis, Ulster University). Retrieved March 3, 2025 from https://pure.ulster.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/psychological-and-physiological-factors-that-affect-success-in-ul

- Thornton, O. R., Li, W., Cole, H., & Cólon, I. (2023). Borderline personality disorder and neuroplasticity: A review. International Neuropsychiatric Disease Journal, 19(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.9734/indj/2023/v19i2367

- Workman, L., & Reader, W. (2015). Evolutionary psychology: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Zhang, W., He, L., Chen, Y., & Gao, X. (2024). The relationship between big five personality traits and fear of missing out: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 230, 112788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.112788

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College