How Background Information Influences Reading Understanding:

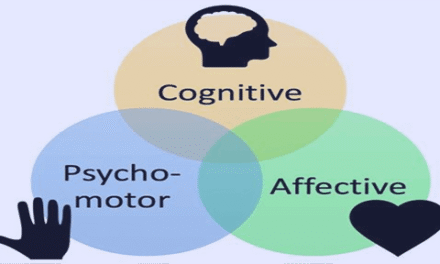

Reading comprehension is a complex cognitive process that involves the interaction between the reader’s prior knowledge, language skills, and text characteristics. One crucial factor that significantly impacts this process is background information. Background information refers to the reader’s pre-existing knowledge and experiences that shape their understanding of a given text. It plays a vital role in decoding meanings, making inferences, and connecting ideas while reading. This article delves into the multifaceted relationship between background information and reading comprehension, exploring how background information influences reading understanding. By examining the cognitive mechanisms involved and providing practical implications, we can gain valuable insights into enhancing reading comprehension strategies.

The Role of Background Information in Reading Comprehension:

Background information serves as a foundation upon which new information is processed and integrated. When readers encounter a text, they actively connect the presented information with their existing knowledge. This connection enables them to form a coherent mental representation of the text’s content. Without relevant background knowledge, the process of comprehension can be hindered, leading to confusion, misinterpretation, and incomplete understanding.

Activation of Prior Knowledge:

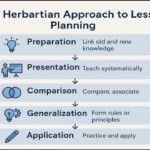

Background information acts as a cognitive scaffold that aids in the activation of prior knowledge. As readers engage with a text, their existing schema—mental frameworks of knowledge—related to the subject matter are activated. These schemata guide the reader’s expectations and help predict the direction of the text. For example, someone with a strong background in history will better understand a historical novel by accurately interpreting the cultural and historical context.

Inference and Interpretation:

Effective reading comprehension often involves making inferences—drawing logical conclusions that are not explicitly stated in the text. Background information plays a critical role in this process. Readers use their prior knowledge to fill in gaps and make connections between ideas. For instance, if a text mentions “Eiffel Tower” without further description, a reader with background knowledge of Paris can infer that the text is referring to the iconic landmark in France.

- The Essence of Inference and Interpretation: Inference and interpretation involve going beyond the literal text to uncover implied meanings, make predictions, and grasp subtle nuances. While reading, readers use their background knowledge and context clues to fill in gaps and create a cohesive mental representation of the content.

- Making Connections: Readers link information within the text to their prior knowledge, allowing them to draw conclusions and infer relationships between ideas.

- Identifying Themes: Inference and interpretation help uncover the underlying themes, messages, and motifs that authors weave into their narratives.

- Predicting Outcomes: Readers use clues from the text to predict future developments, fostering a sense of anticipation and engagement.

- The Role of Background Information: Background information acts as a critical foundation for inference and interpretation. A reader’s existing knowledge, experiences, and cultural awareness provide the necessary context to make accurate inferences.

- Cultural Context: Background knowledge of cultural norms and practices helps readers understand characters’ actions and motivations in culturally rich narratives.

- Domain-specific Knowledge: In texts involving technical or specialized subjects, readers with relevant background knowledge can infer meanings that might elude those without such expertise.

- Challenges and Benefits: While inference and interpretation enrich reading comprehension, they also present challenges:

- Ambiguity: Authors often employ ambiguity to evoke multiple interpretations. While this adds depth, readers must navigate uncertainty.

- Misinterpretation: Inference involves assumptions that can lead to misinterpretations. A reader’s background knowledge might guide them toward unintended conclusions.

However, the benefits of developing inference and interpretation skills outweigh these challenges:

- Critical Thinking: These skills cultivate critical thinking by encouraging readers to question, analyze, and engage with the text on a deeper level.

- Engagement: Inference and interpretation promote active engagement, transforming reading from a passive absorption of information into an interactive exploration of ideas.

- Practical Strategies for Cultivating Inference and Interpretation: Readers and educators can employ various strategies to enhance inference and interpretation skills:

- Questioning: Encourage readers to ask questions while reading. What do they predict will happen next? How do characters’ motivations align with their actions?

- Discussion: Engage in group discussions that explore various interpretations. Hearing diverse viewpoints challenges assumptions and broadens understanding.

- Textual Evidence: Teach readers to support their inferences with evidence from the text. This practice sharpens analytical skills and reinforces conclusions.

- Literary and Non-literary Texts: Inference and interpretation are equally applicable to both literary and non-literary texts:

- Literary Texts: Inference brings out the symbolism, metaphors, and allegories that enrich literary works, inviting readers to explore layers of meaning.

- Non-literary Texts: These skills are valuable in informational texts too. Readers infer cause-and-effect relationships, author biases, and intended messages.

- Lifelong Skill Development: Inference and interpretation are skills that evolve over time:

- Wide Reading: Exposure to diverse genres and authors hones the ability to detect patterns, conventions, and subtle hints.

- Reflection: Regularly revisiting texts and analyzing one’s initial inferences fosters a deeper understanding of the complexity of interpretation.

Vocabulary and Terminology:

Background information significantly influences vocabulary comprehension. Readers familiar with specialized terminology related to the topic being discussed are more likely to correctly interpret and understand the text. A lack of relevant background knowledge can lead to confusion and misinterpretation of domain-specific vocabulary.

- Vocabulary’s Impact on Comprehension: Vocabulary is the cornerstone of language comprehension. The words used in a text carry specific meanings, and readers must be familiar with these meanings to fully understand the content. A robust vocabulary enhances comprehension by:

- Decoding Words: Familiar words are quickly recognized and processed, allowing readers to focus on understanding the overall message rather than struggling with individual word meanings.

- Inferencing: A rich vocabulary enables readers to infer the meanings of unfamiliar words based on context, leading to a more complete understanding of the text.

- Precision: Well-chosen vocabulary helps authors convey precise meanings and nuances, which readers with a strong vocabulary can appreciate.

- Domain-specific Terminology: Texts in various disciplines often include specialized terminology specific to those fields. Familiarity with domain-specific terms is essential for comprehending technical, scientific, or academic content.

- Scientific Literature: Readers with a background in science can readily grasp the terminology used in research papers and scientific articles, facilitating their comprehension of complex concepts.

- Legal Documents: Legal texts are laden with specialized jargon that only those trained in law can fully understand, highlighting the importance of background knowledge in specific fields.

- Challenges in Vocabulary Comprehension: Challenges related to vocabulary and terminology can impede reading comprehension, particularly for readers with limited prior exposure to certain words or concepts:

- Limited Vocabulary: Readers with a limited vocabulary might struggle to grasp the full meaning of a text, leading to misinterpretations or a shallow understanding.

- Cultural Barriers: Vocabulary can carry cultural connotations that may not translate accurately across languages or cultures. These barriers can hinder comprehension for non-native speakers.

- Practical Implications for Enhancing Vocabulary and Terminology: Empowering readers to develop a strong vocabulary and grasp domain-specific terminology requires a combination of strategies and approaches:

- Context Clues: Encourage readers to rely on context clues to infer the meanings of unfamiliar words. This fosters critical thinking and a deeper understanding of how language works.

- Vocabulary-building Activities: Engage readers in activities that introduce new words and concepts. These can include word games, vocabulary exercises, and exposure to a wide range of texts.

- Reading Widely: Expose readers to diverse genres, topics, and writing styles. This exposure not only broadens their vocabulary but also introduces them to various linguistic nuances.

- Digital Tools and Resources: In the digital age, various tools and resources can aid readers in enhancing their vocabulary and terminology comprehension:

- Dictionaries and Thesauruses: Online dictionaries and thesauruses provide quick access to word meanings, synonyms, and antonyms, helping readers expand their vocabulary.

- Language Learning Apps: Language learning apps offer interactive ways to learn new words, practice pronunciation, and reinforce vocabulary through quizzes and games.

- Lifelong Learning: Vocabulary and terminology development is an ongoing process. Readers can continue to expand their language skills throughout their lives by:

- Reading Regularly: Reading a variety of materials—books, articles, newspapers—exposes readers to new words and usage patterns.

- Note-taking: Jotting down unfamiliar words and their meanings while reading creates a personal vocabulary bank for future reference.

- Cultivating Curiosity: Encourage readers to explore unfamiliar topics and engage with challenging content. This curiosity-driven approach naturally exposes them to new vocabulary.

Cultural and Contextual Understanding:

Cultural and contextual cues are essential for grasping the nuances of a text. Background information encompassing cultural norms, historical events, and societal contexts aids in understanding the underlying meanings and connotations. Readers from different cultural backgrounds might interpret a text differently based on their unique experiences and knowledge.

- Cultural Nuances: Cultural nuances encompass the intricate elements of a society’s values, beliefs, customs, and behaviors. Readers from different cultural backgrounds bring their unique experiences and perspectives to their reading, which can either enrich or complicate the comprehension process.

- Idioms and Phrases: Cultural expressions, idioms, and sayings are often deeply rooted in specific cultural contexts. A reader unfamiliar with these expressions might struggle to grasp their intended meanings.

- Social Norms: Characters’ actions and interactions in a story can be interpreted differently based on cultural norms. What is considered polite or rude, acceptable or taboo, varies across cultures.

- Historical and Societal Contexts: Historical and societal contexts provide the backdrop against which a text’s events unfold. Readers with a solid understanding of the relevant historical and societal factors can more accurately interpret the motivations, conflicts, and themes within a text.

- Historical Novels: A reader familiar with the historical events of a particular era can appreciate the authenticity of a historical novel’s setting and characters.

- Political Satire: Understanding the political climate of a certain time period helps readers grasp the satire and commentary embedded in political literature.

- Cross-cultural Interpretation: Readers from diverse cultural backgrounds might interpret a text differently due to their distinct reference points. A word, phrase, or symbol that holds significance in one culture may carry a different meaning—or no meaning at all—in another.

- Religious Symbols: Religious symbols and references can be deeply meaningful to some readers while being entirely unfamiliar or even misunderstood by others.

- Geography and Place Names: Readers with knowledge of a specific geographical area might connect more deeply to texts that reference their homeland.

- Empathy and Connection: Cultural and contextual understanding facilitates empathy and connection between readers and characters. When readers comprehend the cultural factors shaping a character’s experiences, they can better empathize with their struggles, desires, and decisions.

- Global Literature: Exposure to literature from different cultures encourages readers to step into the shoes of characters from diverse backgrounds, fostering empathy and cross-cultural understanding.

- Broadened Horizons: Engaging with texts set in different countries or time periods broadens readers’ horizons and nurtures their appreciation for the diversity of human experiences.

- Practical Implications: Educators and learners can implement strategies to enhance cultural and contextual understanding, promoting more effective reading comprehension:

- Diverse Reading Lists: Curate reading materials that represent a variety of cultures, languages, and historical contexts. This exposure helps readers expand their perspectives and appreciate different viewpoints.

- Discussion and Reflection: Encourage readers to engage in discussions about cultural and contextual influences on texts. This reflective practice deepens comprehension and encourages critical thinking.

- Research and Exploration: Encourage readers to explore the cultural and historical context of a text before and after reading. This research can provide valuable insights into the motivations and meanings behind the content.

The Interaction of Background Information with Textual Features:

The process of reading comprehension is a dynamic interaction between the reader’s background information and the various features embedded within a text. These textual features, such as style, tone, structure, and language use, influence how readers interpret and understand the content. The interplay between background information and these textual elements is a complex dance that significantly impacts the overall comprehension experience.

- Style and Tone: The style and tone of a text play a pivotal role in shaping the reader’s emotional and intellectual response. A reader’s background information can heavily influence how they perceive and respond to the style and tone of a text. For instance:

- A reader with a background in literature might appreciate and understand the nuances of a text that employs intricate metaphors and symbolism.

- Readers familiar with formal academic writing may be more attuned to the tone of objectivity and authority in scholarly articles.

- Background knowledge affects how readers perceive humor, sarcasm, irony, and emotional cues in the text. Without an understanding of cultural or contextual references, a reader might misinterpret a humorous statement, leading to confusion or even offense.

- Language Use and Vocabulary: The language used in a text, including its vocabulary and sentence structure, can either facilitate or hinder comprehension depending on the reader’s background knowledge. Readers with a broad vocabulary and familiarity with domain-specific terms will have an easier time understanding complex texts. However, readers without such background knowledge may struggle to grasp the intended meanings.

- A reader well-versed in medical terminology will readily understand a scientific paper on a medical breakthrough.

- On the other hand, a reader without a background in law might find legal documents challenging due to their specialized language.

- Structure and Organization: The structure and organization of a text guide readers through the content and highlight key points. A reader’s background knowledge influences their ability to navigate and extract meaning from this structure. For example:

- A reader familiar with the structure of a research paper (abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion) will quickly locate and comprehend specific information.

- In narrative texts, readers with background knowledge of storytelling conventions can better anticipate plot developments and understand character motivations.

- Cultural and Historical References: Many texts include cultural and historical references that enhance meaning and depth. A reader’s background knowledge significantly affects their ability to grasp these references. A historical event, literary allusion, or cultural symbol can carry layers of meaning that resonate differently based on the reader’s familiarity:

- A reader knowledgeable about Greek mythology will recognize the significance of references to gods and myths in a novel.

- Readers from different cultures may interpret a historical reference differently due to variations in their background information.

- Figurative Language and Imagery: Authors often use figurative language and imagery to convey abstract concepts and evoke emotions. A reader’s background knowledge contributes to their ability to decipher and appreciate these elements. Consider:

- A reader with a background in art might appreciate and interpret metaphors involving color and composition more deeply.

- Readers with cultural background knowledge can relate to metaphors rooted in specific cultural contexts.

- Genre-specific Conventions: Different genres have their own conventions and expectations. A reader’s familiarity with these conventions greatly influences how they engage with the text. For instance:

- A reader accustomed to reading scientific articles will know to look for citations, data, and methodology in a research paper.

- A background in detective fiction helps readers navigate clues, red herrings, and narrative twists in mystery novels.

Challenges and Limitations in Leveraging Background Information for Reading Comprehension:

While the role of background information in enhancing reading comprehension is undeniable, it’s important to acknowledge the challenges and limitations that can arise when relying on prior knowledge. These challenges can impact the accuracy, objectivity, and inclusivity of comprehension processes. By understanding and addressing these potential drawbacks, educators and learners can develop more effective strategies for leveraging background information.

1. Confirmation Bias: Confirmation bias is a cognitive bias that leads individuals to seek out and interpret information in a way that confirms their pre-existing beliefs or assumptions. When readers rely heavily on their background knowledge, they may unintentionally filter out information that contradicts their existing understanding. This can lead to an incomplete or skewed interpretation of the text, hindering the pursuit of unbiased comprehension.

Mitigation: Encourage readers to approach texts with an open mind, actively seeking out information that challenges their assumptions. Incorporate diverse perspectives and sources of information to foster a well-rounded understanding of the topic.

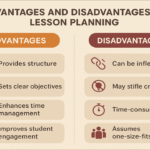

2. Varied Levels of Background Knowledge: Readers come from diverse backgrounds and have varying levels of exposure to different subjects and experiences. A text that assumes a certain level of background knowledge can alienate readers who lack that knowledge, leading to confusion and disengagement. Conversely, texts that overly simplify concepts to cater to a wide audience can bore and frustrate readers with more advanced knowledge.

Mitigation: Authors and educators should strike a balance between providing sufficient context for newcomers to the subject while offering insights or nuances that can engage readers with more advanced background knowledge. Additionally, fostering an inclusive learning environment where learners can share their diverse perspectives can enhance comprehension for everyone.

3. Potential Misinterpretations: Readers with different backgrounds may interpret the same text in multiple ways due to their unique cognitive schemata. The same metaphor, analogy, or cultural reference might be understood differently based on individual experiences. This can lead to miscommunication and misunderstandings, particularly in discussions or collaborative settings.

Mitigation: Encourage readers to engage in reflective discussions where they explore different interpretations. Encourage them to unpack their assumptions and explain their thought processes, promoting a deeper understanding of how background information influences their comprehension.

4. Narrowed Focus: When readers possess extensive background knowledge in a particular field, they may become excessively focused on specific aspects of a text that align with their expertise. This focus could lead them to overlook broader themes or connections within the text, limiting their overall comprehension.

Mitigation: Encourage readers to periodically step back and assess the text from a broader perspective. Engage in activities that encourage exploration of unfamiliar or peripheral concepts to expand the scope of comprehension.

5. Evolving Knowledge: Background knowledge is not static; it evolves over time with new experiences and learning. As a result, what was once relevant and accurate might become outdated or insufficient. Relying solely on past knowledge without updating it can lead to misconceptions or inaccuracies in comprehension.

Mitigation: Promote a growth mindset where readers recognize the value of continuous learning. Encourage them to stay informed about developments in various fields to ensure that their background knowledge remains relevant and accurate.

6. Cross-cultural Differences: Cultural differences can significantly impact the interpretation of texts. Readers from diverse cultural backgrounds may not share the same background knowledge or cultural references, leading to misunderstandings or misinterpretations.

Mitigation: When dealing with cross-cultural communication, authors and educators should be mindful of potential cultural gaps. Providing additional context for cultural references or using universally understood examples can help bridge these gaps.

Practical Implications for Enhancing Reading Comprehension:

Enhancing reading comprehension through the effective utilization of background information involves a combination of strategies aimed at activating prior knowledge, building a diverse foundation of background knowledge, encouraging critical thinking, and providing contextual support. These practical implications can be applied in educational settings, self-directed learning, and even professional contexts to improve overall reading understanding.

- Activating Prior Knowledge: Activating prior knowledge is a fundamental step in preparing readers for effective comprehension. By helping readers connect new information to what they already know, educators and learners can improve retention and understanding. Here’s how:

- Pre-reading Activities: Before diving into a text, engage learners in discussions, brainstorming sessions, or short quizzes related to the topic. This primes their cognitive schema and prepares them to process the upcoming content.

- KWL Charts: Use KWL (Know-Want to Know-Learn) charts to encourage students to list what they already know about a topic, what they want to know, and what they have learned after reading. This structure promotes the activation of prior knowledge and sets a purpose for reading.

- Building Background Knowledge: To enhance comprehension across diverse subjects, it’s essential to build a strong foundation of background knowledge. This can be achieved through intentional instruction and exposure to various domains of knowledge:

- Interdisciplinary Learning: Encourage learners to explore topics beyond their immediate interests. Incorporate interdisciplinary projects that expose them to new subjects and broaden their horizons.

- Vocabulary Development: Systematically teach domain-specific vocabulary to ensure readers have the necessary language tools to comprehend complex texts. Frequent exposure to new words and their meanings aids in understanding and retention.

- Encouraging Critical Thinking: Promoting critical thinking about the relationship between background knowledge and text content helps readers become more discerning and nuanced in their interpretations:

- Comparative Analysis: Encourage readers to compare their existing knowledge with the information presented in the text. This practice helps them identify gaps, contradictions, or biases in their understanding.

- Identifying Assumptions: Have readers reflect on their assumptions and biases while reading. Encourage them to consider how their background knowledge might be influencing their interpretations.

- Providing Contextual Support: Authors and educators can play a significant role in enhancing comprehension by offering context that aids readers in understanding complex or unfamiliar subjects:

- Clear Definitions: When introducing new terminology, provide clear and concise definitions within the text or through footnotes. This reduces the cognitive load and prevents readers from getting stuck on unfamiliar words.

- Visual Aids: Incorporate visuals, such as diagrams, maps, or infographics, to visually represent concepts and relationships. Visual aids provide additional context and facilitate understanding.

- Cultural and Historical Context: For texts that involve cultural or historical references, provide a brief background to ensure readers comprehend the significance of these elements.

- Real-world Applications: Applying these practical implications in educational, personal, and professional contexts can lead to significant improvements in reading comprehension:

- Classroom Settings: Educators can design lesson plans that incorporate pre-reading activities, encourage cross-disciplinary exploration, and stimulate critical thinking. These strategies create an interactive and engaging learning environment.

- Self-directed Learning: Self-learners can actively seek out diverse sources of information, challenge their assumptions, and reflect on how their background knowledge shapes their understanding. This approach cultivates a habit of metacognition, leading to deeper comprehension.

- Professional Reading: In professional settings, individuals can apply these strategies to better understand complex documents, reports, and research papers. Critical evaluation of their background knowledge and contextual understanding ensures accurate interpretation.

In conclusion, the influence of background information on reading comprehension is profound and multifaceted. It shapes the way readers interact with texts, guiding their understanding, interpretation, and inference-making processes. Recognizing the intricate interplay between background knowledge and textual content can empower educators and learners to optimize reading comprehension strategies. By actively cultivating a rich and diverse foundation of background knowledge, readers can enhance their ability to engage with texts across various subjects and genres. As we continue to explore the complexities of the human mind and its interaction with written language, a deeper understanding of how background information influences reading comprehension will undoubtedly contribute to more effective communication and learning.

Frequently Asked Questions [FAQs]:

What is reading comprehension?

Reading comprehension is the ability to understand, interpret, and make meaning from written texts. It involves actively engaging with the content, connecting it to prior knowledge, making inferences, and grasping the deeper meanings conveyed by the author.

Why is reading comprehension important?

Reading comprehension is essential for effective communication, learning, and critical thinking. It enables readers to extract information, analyze arguments, and engage with various types of texts, from academic articles to fictional stories.

How does background information influence reading comprehension?

Background information serves as the foundation for understanding a text. It helps activate prior knowledge, aids in making connections, allows for inferencing, and contextualizes cultural references. Readers’ existing experiences and knowledge greatly impact how they interpret and engage with content.

How can educators enhance students’ reading comprehension?

Educators can foster reading comprehension by incorporating strategies such as pre-reading activities to activate prior knowledge, encouraging discussions to explore different interpretations, and promoting critical thinking through analysis of text elements.

What role does vocabulary play in reading comprehension?

Vocabulary is essential for understanding the meanings of words within a text. A robust vocabulary enables readers to decode text efficiently, infer meanings from context, and engage with specialized terminology.

How does making inferences contribute to comprehension?

Making inferences involves drawing conclusions based on available information. It helps readers uncover implied meanings, predict outcomes, and bridge gaps within a text, resulting in a deeper understanding of the content.

How does cultural understanding impact reading comprehension?

Cultural understanding allows readers to interpret the nuances, context, and references within a text accurately. It aids in comprehending cultural norms, historical allusions, and societal influences that contribute to the author’s intended meaning.

What are some practical strategies for improving reading comprehension?

Strategies include activating prior knowledge before reading, asking questions to stimulate engagement, seeking diverse reading materials to broaden perspectives, and practicing inferencing and critical thinking through discussions.

Can reading comprehension be improved over time?

Absolutely. Reading comprehension is a skill that can be developed and refined through consistent practice, exposure to varied texts, active engagement, and a willingness to reflect on and refine one’s reading strategies.

How do digital resources support reading comprehension?

Digital tools such as online dictionaries, language learning apps, and e-books offer immediate access to word meanings, interactive learning opportunities, and tools to engage with texts, enhancing vocabulary and comprehension skills.

Is reading comprehension important in non-literary contexts?

Yes, reading comprehension is crucial in both literary and non-literary contexts. It aids in understanding technical documents, news articles, scientific research, legal texts, and any other written content that conveys information or ideas.

Can background information lead to biased interpretations?

Yes, relying solely on background knowledge can lead to confirmation bias, where readers only seek information that aligns with their existing beliefs. It’s important to be aware of potential biases and consider multiple viewpoints.

How can readers navigate texts with domain-specific terminology?

Readers can enhance their understanding of domain-specific terminology by actively learning key terms, seeking definitions within the text or through supplementary resources, and exploring related materials to build a strong foundation of knowledge.

Can readers with different cultural backgrounds interpret texts differently?

Absolutely. Cultural backgrounds influence readers’ interpretations based on their unique experiences and perspectives. Readers from different cultures may interpret references, themes, and connotations differently, highlighting the richness of diverse viewpoints.

Can children develop reading comprehension skills early on?

Yes, children can begin developing reading comprehension skills at an early age. Encouraging interactive reading, discussing stories, asking questions, and exposing them to a variety of genres and topics all contribute to skill development.

How can one become a better reader overall?

Becoming a better reader involves consistent practice, a wide range of reading materials, active engagement with texts, reflecting on one’s understanding, seeking diverse perspectives, and maintaining a curious and open-minded approach to learning.

Is there a relationship between reading comprehension and critical thinking?

Yes, reading comprehension and critical thinking are closely interconnected. Effective comprehension involves analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information from a text, which are key components of critical thinking skills.

Can reading comprehension be improved through self-directed learning?

Absolutely. Engaging in self-directed learning, exploring diverse topics, actively reflecting on readings, and seeking out challenging materials can all contribute to enhancing reading comprehension skills.

How does context influence vocabulary comprehension?

Context provides clues to the meanings of unfamiliar words within a text. By understanding the context in which a word is used, readers can infer its meaning and contribute to their overall comprehension.

Can practicing reading comprehension lead to better writing skills?

Yes, practicing reading comprehension can positively impact writing skills. Reading exposes writers to different writing styles, vocabulary usage, and effective communication strategies, contributing to their ability to express ideas coherently and effectively.

References:

- Adcock, D., & Davies, S. (2012). Comprehensive assessment of reading strategies. Cheltenham, VIC: Haer Hawker Brownlow Education.

- Adcock, D., & Krensky, J. (2012). Strategies to achieve reading success. Cheltenham, VIC: Hawker Brownlow Education.

- Alexander, P. A., & Jetton, T. L. (2000). Learning from text: A multidimensional and developmental perspective. Handbook of Reading Research, 3(1), 285–310.

- Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In Psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 8, pp. 47–89). Stirling, Scotland: Elsevier.

- Barnes, M. A., Dennis, M., & Haefele-Kalvaitis, J. (1996). The effects of knowledge availability and knowledge accessibility on coherence and elaborative inferencing in children from six to fifteen years of age. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 61(3), 216–241.

- Beck, I. L., & McKeown, M. G. (1991). Research directions: Social studies texts are hard to understand: Mediating some of the difficulties. Language Arts, 68(6), 482–490.

- Beck, I. L., Omanson, R. C., & McKeown, M. G. (1982). An instructional redesign of reading lessons: Effects on comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 17(4), 462–481.

- Berkowitz, S., & Taylor, B. (1981). The effects of text type and familiarity on the nature of information recalled by readers. In M. Kamil (Ed.), Directions in reading: Research and instruction (pp. 157–161). Washington, DC: National reading Conference.

- Best, R. M., Floyd, R. G., & McNamara, D. S. (2008). Differential competencies contributing to children’s comprehension of narrative and expository texts. Reading Psychology, 29(2), 137–164.

- Borges, A. T. (1999). Como evoluem os modelos mentais. Ensaio Pesquisa em Educação em Ciências (Belo Horizonte), 1(1), 66–92.

- Cain, K., & Oakhill, J. V. (1999). Inference making ability and its relation to comprehension failure in young children. Reading and Writing, 11(5/6), 489–503.

- Cain, K., Oakhill, J. V., Barnes, M. A., & Bryant, P. E. (2001). Comprehension skill, inference-making ability, and their relation to knowledge. Memory & Cognition, 29(6), 850–859.

- Callahan, D., & Drum, P. A. (1984). Reading ability and prior knowledge as predictors of eleven and twelve year olds’ text comprehension. Reading Psychology, 5(1–2), 145–154.

- Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1), 5–51.

- Cervetti, G. N., & Wright, T. S. (2020). The role of knowledge in understanding and learning from text. Handbook of Reading Research, 5, 237–260.

- Cervetti, G. N., Wright, T. S., & Hwang, H. (2016). Conceptual coherence, comprehension, and vocabulary acquisition: A knowledge effect? Reading and Writing. An Interdisciplinary Journal, 29(4), 761–779.

- Chiesi, H. L., Spilich, G. J., & Voss, J. F. (1979). Acquisition of domain-related information in relation to high and low domain knowledge. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18(3), 257–273.

- Connor, M. C. ,Dombek, J., Crowe, E. C., Spencer, M., Tighe, E. L., Coffinger, S., Zargar, E., Petscher, Y. (2017). Acquiring science and social studies knowledge in kindergarten through fourth grade: Conceptualization, design, implementation, and efficacy testing of content-area literacy instruction (CALI). Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(3), 301–319.

- Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1997). Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 934–935.

- Dewitz, P.,Carr, E., &Patberg, J. (1987). Effects of inference training on comprehension and comprehension monitoring. Reading Research Quarterly, 22(1), 99–121.

- Dochy, F., Segers, M., & Buehl, M. M. (1999). The relation between assessment practices and outcomes of studies: The case of research on prior knowledge. Review of Educational Research, 69(2), 145–186.

- Dole, J. A., Nokes, J. D., & Drits, D. (2009). Cognitive strategy instruction. In S. E. Israel & G. G. Duffy (Eds.), Handbook of research on reading comprehension. New York: Routledge New York.

- Elleman, A. M. (2017). Examining the impact of inference instruction on the literal and inferential comprehension of skilled and less skilled readers: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(6), 761–781.

- Ericsson, K. A., & Kintsch, W. (1995). Long-term working memory. Psychological Review, 102(2), 211–245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.211

- Freebody, P., & Anderson, R. C. (1983). Effects of vocabulary difficulty, text cohesion, and schema availability on reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 18(3), 277–294.

Assistant Teacher at Zinzira Pir Mohammad Pilot School and College