The research design refers to the overall plan or strategy for conducting a research study. It outlines the framework of the entire research process, including the research question, hypothesis, data collection and analysis methods, and overall approach. Research design is a crucial aspect of conducting any research project as it serves as a blueprint for researchers to follow to ensure that the research is valid, reliable, and replicable. The research design also helps to ensure that the data collected is relevant and can be used to draw meaningful conclusions about the research question being investigated. There are many different research designs, including experimental designs, observational studies, surveys, and case studies, among others. Each research design has its strengths and weaknesses, and researchers must choose the design that is best suited for their research question and objectives. In the rest of this article, we will explore the types of research designs and how to choose a research design.

Definitions of Research Design:

Here are some definitions of research design:

“Research design refers to the blueprint or plan that outlines the procedures and methods to be used in a research study.” (Babbie, 2020)

“Research design is the structure that guides the researcher in the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting observations.” (Trochim & Donnelly, 2006)

“Research design is the plan and structure for the investigation of a problem or issue.” (Creswell, 2018)

“Research design is the framework for the collection and analysis of data that will be used to answer a research question or test a hypothesis.” (Johnson & Christensen, 2014)

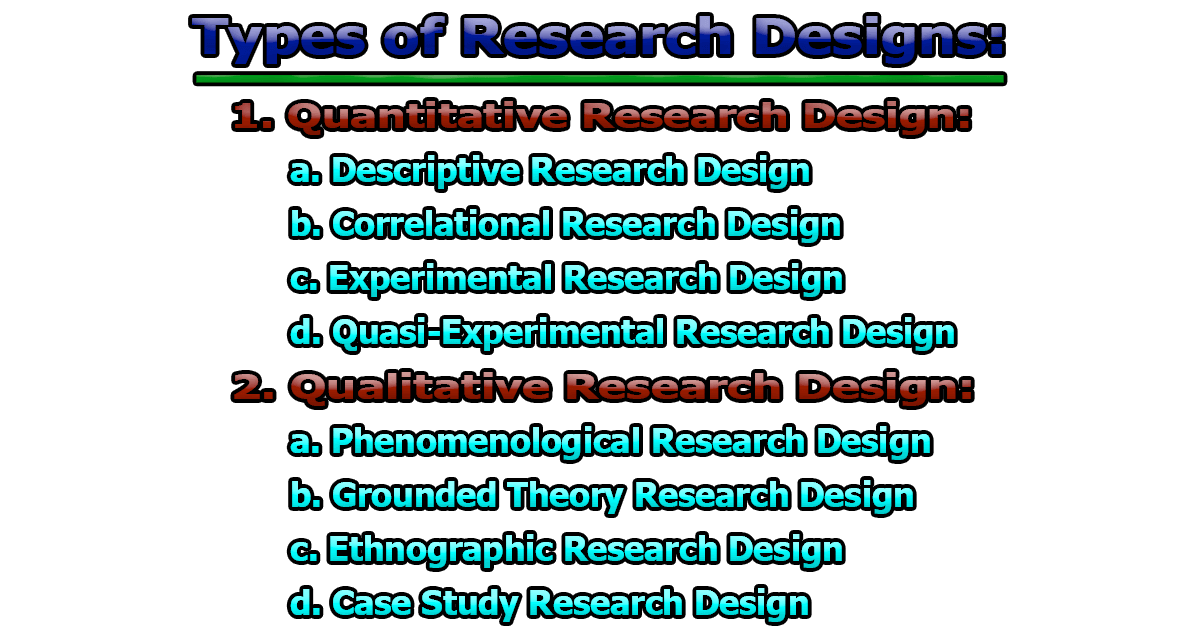

Types of Research Designs:

Understanding the different kinds of research designs is crucial since it ensures that your strategy is appropriate for your research aims, objectives, and questions as well as the resources available to you. Without a clear big-picture notion of how you’ll construct your research, you face the possibility of potentially making methodology decisions that fall out of position, particularly those related to sampling, data collection, and data analysis. Here we’ll explain the most common types of research design for both qualitative and quantitative research projects, whether that is for a full dissertation or thesis, or a smaller research paper or article.

1. Quantitative Research Design: Quantitative research is a structured approach used to collect and analyze numerical data to identify patterns, test theories, and make predictions. It is grounded in the positivist paradigm, which assumes that reality is objective and can be measured using statistical tools (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). This method is commonly used in the social sciences, health, education, and other fields that require empirical evidence to support hypotheses.

Quantitative research designs are broadly categorized into four main types: descriptive, correlational, experimental, and quasi-experimental. Each of these designs serves a different purpose and varies in terms of the level of control, manipulation, and causal inference.

a. Descriptive Research Design: Descriptive research is often the first step in quantitative inquiry. It aims to describe the characteristics of a population, phenomenon, or situation without attempting to determine cause-and-effect relationships (Babbie, 2020). This type of research is useful for developing a detailed profile of variables as they naturally occur.

Key Features:

- Focuses on “what is” rather than “why” or “how”

- Variables are not manipulated

- Often used in needs assessments, demographic studies, and institutional evaluations

Example: A university might conduct a survey to determine how often students use digital library resources. The results may show that 70% of students prefer using online databases over physical books. This information helps institutions plan services without inferring why those preferences exist (Gay, Mills, & Airasian, 2012).

Common Methods:

- Surveys and questionnaires

- Observational studies

- Document analysis

Descriptive research contributes foundational knowledge for later hypothesis testing or comparative studies.

b. Correlational Research Design: Correlational research examines the relationships between two or more variables to determine whether and how they are associated. It does not involve manipulation of variables but rather observes them as they naturally occur. The goal is to measure the direction and strength of relationships using statistical techniques (Privitera, 2024).

Key Features:

- Determines the degree and direction of relationships

- No random assignment or manipulation

- Can identify predictive relationships but not causation

Example: A researcher may study the correlation between students’ GPA and the number of hours they spend in the library each week. A positive correlation would indicate that more library usage is associated with higher GPAs, but this does not prove that library usage causes academic success (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Statistical Tools:

- Pearson’s r for linear relationships

- Spearman’s rho for ordinal data

- Regression analysis for prediction

Correlational designs are especially valuable in educational and social science research where ethical or practical constraints limit experimentation.

c. Experimental Research Design: Experimental research is considered the gold standard for determining causal relationships. It involves manipulating an independent variable and measuring its effect on a dependent variable, with participants randomly assigned to experimental and control groups (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). This randomization helps control for confounding variables and enhances internal validity.

Key Features:

- Random assignment to groups

- Manipulation of variables

- Control of extraneous factors

- High internal validity

Example: Suppose researchers want to test the effectiveness of a new online information literacy course. Students are randomly divided into two groups: one uses the new course, while the other uses traditional instruction. After four weeks, both groups take the same assessment, and scores are compared to evaluate the intervention’s effectiveness (Cook & Campbell, 1979).

Components:

- Pre-test and post-test measurements

- Use of control/placebo groups

- Laboratory or controlled settings

Because of its rigorous nature, experimental research is often used in the health sciences, psychology, and educational testing.

d. Quasi-Experimental Research Design: Quasi-experimental research is similar to experimental design, but lacks random assignment, often due to ethical, logistical, or practical limitations. Researchers still manipulate an independent variable but must work with pre-existing groups (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). As a result, internal validity is lower, and confounding variables are more difficult to control.

Key Features:

- Involves intervention or manipulation

- No randomization

- Often conducted in real-world settings

Example: A university library implements a new mobile app to support students at one campus, while another campus continues using the standard web interface. Researchers compare usage statistics and student feedback from both campuses. Although the groups weren’t randomly assigned, the study still provides valuable insights into the app’s effectiveness (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Design Variants:

- Nonequivalent group design

- Time-series design

- Pre-test/post-test with non-random groups

Quasi-experiments are commonly used in educational reform evaluations, institutional programs, and policy impact studies where randomized control is not feasible.

Summary Comparison:

| Design Type | Manipulation | Random Assignment | Purpose | Causality |

| Descriptive | No | No | Describe variables | No |

| Correlational | No | No | Examine relationships | No |

| Experimental | Yes | Yes | Determine cause-and-effect | Yes |

| Quasi-Experimental | Yes | No | Estimate causal effects in real-world contexts | Partial |

2. Qualitative Research Design: Qualitative research is an approach that seeks to understand human experiences, social processes, and cultural meanings through rich, descriptive data. Rather than relying on numerical data, qualitative research emphasizes depth over breadth, using open-ended methods such as interviews, observations, and document analysis to explore how individuals interpret their lived realities (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Although qualitative research encompasses a variety of designs, this section focuses on the “Big 4” designs that are widely recognized and applied across academic disciplines: phenomenological design, grounded theory design, ethnographic design, and case study design.

a. Phenomenological Research Design: Phenomenology focuses on exploring how individuals perceive and experience a specific phenomenon, aiming to uncover the essence of that experience. Rooted in the philosophical work of Edmund Husserl, phenomenology emphasizes bracketing—suspending the researcher’s biases to fully grasp participants’ perspectives (Moustakas, 1994).

Key Features:

- Investigates lived experiences

- Small sample sizes (often 5–25 participants)

- In-depth interviews as primary data source

- Focus on essence or meaning of the experience

Example: A researcher interested in understanding the emotional and cognitive experiences of academic librarians during the transition to digital services might conduct in-depth interviews with several librarians, aiming to extract common themes of stress, adaptation, and professional identity (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Analytical Process:

- Identifying significant statements

- Clustering into themes

- Describing “what” and “how” participants experienced the phenomenon

Phenomenology is ideal when the goal is to understand the subjective human experience behind a particular event, behavior, or condition.

b. Grounded Theory Research Design: Grounded theory is used when a researcher aims to generate or discover a theory grounded in the data collected from participants. Developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967), this design is highly systematic and involves constant comparison of data to build theoretical categories and relationships.

Key Features:

- Theoretical sampling (selecting participants to build theory)

- Data collection and analysis occur simultaneously

- Use of coding: open, axial, and selective

- Ends with the generation of a substantive or formal theory

Example: A study investigating how university staff adapt to smart library technologies might use grounded theory to develop a model explaining the phases of technological adaptation and resistance among faculty and library personnel (Charmaz, 2014).

Analytical Process:

- Open coding (initial categorization)

- Axial coding (relating categories)

- Selective coding (forming the core theory)

Grounded theory is particularly suitable when no existing theory adequately explains the process under investigation.

c. Ethnographic Research Design: Ethnography involves the immersive study of people and cultures in their natural environments, aiming to understand the social meanings, behaviors, language, and rituals of a specific cultural group (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2019). Rooted in anthropology, ethnography requires prolonged engagement and participant observation.

Key Features:

- Conducted in natural settings

- Participant observation and field notes

- Focus on shared patterns and meanings within a culture

- Researcher becomes part of the setting (“participant-observer”)

Example: An ethnographic study of student behavior in a university library might involve observing daily routines, informal rules, and communal spaces over several months to understand how students co-create learning cultures (Fetterman, 2020).

Data Collection Methods:

- Field notes

- Interviews

- Audio/visual recordings

- Artifact analysis

Ethnography is best when the research aims to deeply understand the norms and practices of a group from an insider’s perspective.

d. Case Study Research Design: Case study research focuses on a bounded system, such as a person, organization, event, or program, and investigates it in-depth within its real-life context (Yin, 2018). It may include multiple sources of data and is often used to explore “how” and “why” questions.

Key Features:

- Bounded by time, place, or activity

- Utilizes multiple data sources (interviews, documents, observations)

- Can be single-case or multiple-case

- Focused on depth rather than generalizability

Example: A researcher might conduct a case study on the implementation of a smart library system at a specific university, examining administrative decisions, staff training, student reactions, and technical challenges over a one-year period (Stake, 1995).

Types of Case Studies:

- Intrinsic: Understanding a unique or interesting case

- Instrumental: Using the case to understand a broader issue

- Collective: Multiple cases studied to explore a phenomenon

Case studies are especially useful when exploring complex systems where the context is integral to understanding the subject.

Summary Comparison:

| Design Type | Focus | Sample Size | Data Collection | Outcome |

| Phenomenology | Lived experiences | Small | In-depth interviews | Description of essence |

| Grounded Theory | Social processes and theory | Moderate | Interviews, memos | Generation of a new theory |

| Ethnography | Cultural patterns and behaviors | Large (group) | Observation, field notes | Cultural interpretation |

| Case Study | In-depth understanding of a case | Varies | Multiple sources | Contextual analysis |

How to Choose a Research Design:

With a wide range of potential research designs available—each tailored to different objectives and methodologies—it is understandable to feel uncertain about selecting the most appropriate one. Choosing the right research design is a critical step that directly affects the validity, feasibility, and outcome of a study. While numerous decision-making frameworks exist, the following key factors can guide researchers in making informed, practical choices.

1. Data Type (Qualitative or Quantitative): The first and most fundamental decision is determining whether your study will rely on qualitative or quantitative data. This distinction shapes every subsequent methodological decision. Quantitative research involves collecting numerical data to test hypotheses and identify statistical relationships (Creswell & Creswell, 2018), whereas qualitative research seeks to understand meanings, experiences, and perspectives through textual or visual data (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Attempting to apply a quantitative research design to qualitative data (or vice versa) is methodologically inappropriate and will undermine the coherence of your study. Therefore, clarity about the nature of your data is a necessary first step.

2. Research Aim(s) and Question(s): Your research aim and questions should directly inform the research design. For example, if your objective is to generate theory from participants’ experiences, a grounded theory design would be suitable (Charmaz, 2014). Conversely, if you aim to measure relationships between independent and dependent variables, an experimental or correlational quantitative design would be more appropriate (Gay, Mills, & Airasian, 2012).

According to Yin (2018), “how” and “why” questions often lend themselves well to case study or qualitative approaches, while questions asking about relationships, impacts, or differences are generally more amenable to quantitative methods. Therefore, always ensure your research design is aligned with the purpose of the inquiry.

3. Time Constraints: The amount of time available for conducting the study is a practical constraint that cannot be overlooked. Certain research designs, such as ethnography or longitudinal studies, require extended fieldwork and repeated observations over time (Fetterman, 2019). If your project has a short timeline—for example, a single academic term or semester—then a more time-efficient design, such as a descriptive survey or a case study, may be more feasible.

Choosing a time-intensive method without the temporal bandwidth to execute it thoroughly can result in superficial data collection and weak analysis, ultimately affecting the credibility of your findings (Marshall & Rossman, 2016).

4. Resource Availability: Resources—such as equipment, funding, personnel, access to participants, and software—also play a pivotal role in determining the feasibility of certain research designs. For instance, experimental research often requires access to specialized labs, controlled environments, or measurement tools, which may not be readily available to all researchers (Campbell & Stanley, 1963).

Similarly, qualitative interviews or focus groups demand significant time, transcription services, and ethical considerations, especially when dealing with vulnerable populations (Tracy, 2019). Before settling on a research design, it is essential to audit the resources you have versus those you would need, and assess whether the gap is bridgeable.

5. Risk Management and Feasibility: A key aspect of research design selection is risk assessment. Projects that rely heavily on uncertain factors—such as hard-to-access populations, extremely large samples, or external collaborations—carry a higher chance of failure. While ambitious designs may offer rich insights, it is often more prudent to select a simpler design that you can execute effectively within your given constraints (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

A well-executed basic methodology typically yields stronger academic outcomes than a complex but poorly implemented one. Furthermore, having contingency plans for potential setbacks (e.g., participant drop-out, technology failure) can safeguard the continuity of the research.

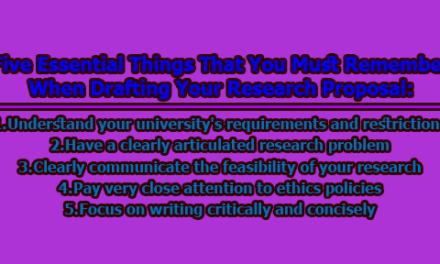

Steps to Choosing a Research Design:

Selecting an appropriate research design is a critical phase in the research process. A well-aligned design ensures that the study can effectively address its research questions, generate meaningful results, and withstand academic scrutiny. The process of choosing a research design involves several interrelated steps, each of which guides the researcher toward methodological coherence and feasibility. Below is a step-by-step approach to making this important decision.

Step 1: Clarify the Research Problem: Before any methodological decisions can be made, the research problem must be clearly defined. This includes identifying the knowledge gap your study intends to fill, the context of the issue, and why the problem is worth investigating.

A well-defined research problem serves as the foundation upon which all design choices are built (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Guiding Questions:

- What is the issue or phenomenon you are investigating?

- Who is affected, and in what context?

- Why is it important to study this?

A vague or overly broad problem will lead to an unfocused design. Narrowing your problem is essential for choosing a targeted and manageable research strategy.

Step 2: Define the Research Objectives and Questions: Once the research problem is clarified, the next step is to articulate precise research objectives and questions. These elements frame what the study aims to achieve and directly influence whether a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods design is appropriate.

Research questions should drive the design, not the other way around (Yin, 2018).

Example:

- If your research question asks “What are the experiences of…”, a qualitative approach may be suitable.

- If your question asks “Does X affect Y…”, a quantitative design may be more appropriate.

Step 3: Determine the Nature of the Data: At this stage, determine whether your study requires numerical data (quantitative) or textual/visual data (qualitative), or a combination of both.

Quantitative:

- Focuses on measurement, frequency, causality

- Requires numerical analysis

- Uses structured instruments like surveys or tests

Qualitative:

- Explores meaning, experience, and interpretation

- Uses interviews, observations, and artifacts

- Aims for depth over breadth

“Quantitative methods are appropriate for testing theories, while qualitative methods are more suited for building them” (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Step 4: Match Design to Research Type: After choosing between qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods, select the specific design that best fits your research aim.

For Quantitative:

- Descriptive: To report characteristics or frequencies

- Correlational: To examine relationships

- Experimental: To determine cause-effect under controlled conditions

- Quasi-experimental: To examine cause-effect in natural settings without randomization

For Qualitative:

- Phenomenology: To explore lived experiences

- Grounded Theory: To develop theory from data

- Ethnography: To study cultural groups in natural settings

- Case Study: To explore a bounded system or case in-depth

Each design has strengths and limitations, so alignment with your research aim is crucial (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Step 5: Evaluate Time and Resource Constraints: Next, assess the practical realities of your research project, including time, access to participants, technical tools, and funding.

- Do you have enough time to conduct interviews or experiments?

- Do you have access to the required population or equipment?

- Are you able to transcribe, code, or statistically analyze your data?

“Feasibility is as important as academic rigor” (Patton, 2015).

If your resources are limited, it may be more realistic to choose a less complex design that can still effectively address your research question.

Step 6: Consider Ethical and Access Issues: Ethical considerations also impact research design. For example, studies involving vulnerable populations, sensitive topics, or intrusive interventions require more rigorous ethical planning and institutional approvals.

- Will you need informed consent?

- Are there confidentiality concerns?

- Is the study intrusive or high-risk?

Ethical feasibility should be assessed early in the design phase (Tracy, 2020).

Step 7: Plan for Validity, Reliability, and Trustworthiness: Each research design must ensure rigor through methodological quality.

For Quantitative:

- Validity: Does the study measure what it intends to?

- Reliability: Are measurements consistent?

For Qualitative:

- Credibility: Are findings believable from the participant’s perspective?

- Transferability: Can findings be applied elsewhere?

- Dependability: Are findings consistent and replicable?

“Designing for trustworthiness is key to credible qualitative research” (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Step 8: Justify Your Design Choice: Finally, be prepared to justify your chosen design both theoretically and practically. Explain how your research questions, data needs, and constraints led you to this decision.

A strong rationale demonstrates that your design:

- Aligns with your research aims

- Is appropriate for your data type

- Is feasible within your constraints

- Meets standards of academic rigor

A well-justified design enhances the credibility and persuasiveness of your research proposal or thesis (Marshall & Rossman, 2016).

In conclusion, research design plays a vital role in determining the success and validity of a study. Understanding the different types—both quantitative and qualitative—and their specific purposes allows researchers to select the most appropriate framework for their inquiry. By aligning the research design with the study’s aims, questions, data type, and practical constraints, researchers can ensure a coherent and effective research process that produces valuable and credible outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is a research design, and why is it important?

A research design is the overall plan or blueprint for conducting a study. It outlines how the research will be carried out, including how data will be collected, analyzed, and interpreted. A well-chosen design helps ensure the study addresses the research problem effectively and that the findings are valid and reliable.

How do I know whether to use qualitative or quantitative research?

The choice between qualitative and quantitative research depends on your research goals and the type of data you need:

- Use qualitative research if you aim to explore experiences, meanings, or processes.

- Use quantitative research if you want to measure variables, test hypotheses, or examine relationships numerically.

If your study requires both, a mixed methods approach might be appropriate.

Can I combine qualitative and quantitative approaches in one study?

Yes, you can. This is called a mixed methods design. It allows you to draw on the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative approaches. For example, you might start with interviews to explore a topic and then follow up with a survey to measure what you discovered.

What is the difference between a research method and a research design?

- A research design is the overall structure or strategy for your study.

- A research method refers to the specific techniques you use to gather and analyze data, such as interviews, surveys, experiments, or observations.

Design is the “what” and “why,” while methods are the “how.”

Which design is best for developing theory from data?

If your goal is to build a theory directly from your data, a grounded theory design is a good choice. It helps you explore patterns, categories, and emerging ideas that form the basis of new theoretical insights.

How do time and resources affect the choice of research design?

Your available time, budget, and access to participants or tools can significantly impact your design choice. For instance, a large-scale experiment or ethnographic study may not be feasible if you’re on a tight schedule or lack resources. Always choose a design that is realistic and achievable given your circumstances.

What design should I use for studying a single organization or group in depth?

A case study design is ideal for exploring a single unit—such as an organization, community, or individual—in rich detail. It allows you to look at a wide range of factors and gain deep insight into the specific context.

Is it acceptable to change my research design mid-project?

While not recommended, sometimes it’s necessary to adjust your design if circumstances change—such as difficulty accessing participants or collecting data. If you do change your design, be sure to clearly document and explain why.

How can I ensure the quality of my study?

Focus on ensuring your study is methodologically sound:

- In quantitative research, aim for valid and reliable measurements.

- In qualitative research, ensure your findings are credible, dependable, and well-supported by the data.

Good planning, transparent procedures, and careful analysis all contribute to high-quality research.

What are the most common mistakes when choosing a research design?

Some common pitfalls include:

- Choosing a design without clearly defining your research questions

- Using a design that doesn’t match your data type

- Underestimating the time or resources required

- Overcomplicating the study when a simpler approach would be more effective

- Failing to justify or explain your choice of design

Careful planning and critical thinking are key to avoiding these issues.

References:

- Babbie, E. (2020). The Practice of Social Research (15th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Campbell, D. T., Stanley, J. C., & Gage, N. L. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Cook, T.D. and Campbell, D.T. (1979) Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

- Creswell, J.W. and Creswell, J.D. (2018) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage, Los Angeles.

- Creswell, J.W. and Poth, C.N. (2018) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing among Five Approaches. 4th Edition, SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Fetterman, D. (Ed.) (2020). Ethnography: Step-by-Step. (Vols. 1-0). SAGE Publications, Inc., https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071909874

- Gay, L.R., Mills, G.E. and Airasian, P.W. (2012) Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Application. 10th Edition, Pearson, Upper Saddle River.

- Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine.

- Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2019). Ethnography (4th ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1512034/ethnography-principles-in-practice-pdf

- Johnson, B. and Christensen, L. (2014) Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches. 5th Edition, SAGE Publications, London.

- Lincoln, Y.S. and Guba, E.G. (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, 289-331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

- Marshall, C. and Rossman, G. (2016) Designing Qualitative Research. 6th Edition, SAGE, Thousand Oaks.

- Moustakas, C. E. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Privitera, G. J. (2024). Statistics for the behavioral sciences (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Patton, M. (2015) Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 4th Edition, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Trochim, W.M. and Donnelly, J.P. (2006) The Research Methods Knowledge Base. 3rd Edition, Atomic Dog, Cincinnati, OH.

- Tracy, S. J. (2019). Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College