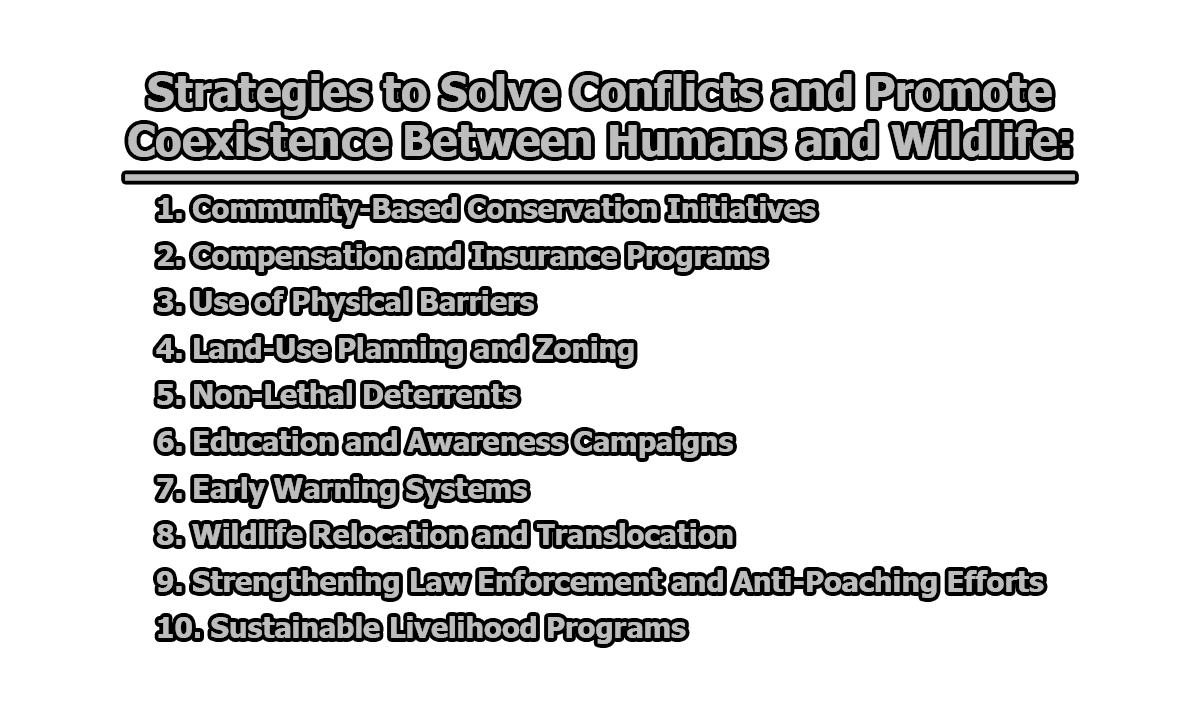

Strategies to Solve Conflicts and Promote Coexistence Between Humans and Wildlife:

Human-wildlife conflict (HWC) occurs when the activities of humans and wildlife negatively affect each other. With growing human populations and expanding development, natural habitats are increasingly encroached upon, leading to more frequent conflicts. These conflicts can result in damage to property, loss of livelihoods, injury or death to both humans and animals, and a decrease in biodiversity. Addressing these issues is crucial for maintaining healthy ecosystems and supporting human communities. Here, we will explore some of the essential strategies to solve conflicts and promote coexistence between humans and wildlife.

1. Community-Based Conservation Initiatives: Involving local communities in wildlife conservation is a powerful strategy for reducing conflicts. By giving local people a stake in the benefits of conservation—whether through tourism, employment, or sustainable harvesting of resources—they are more likely to view wildlife as an asset rather than a threat. Community-based conservation initiatives often involve local decision-making, allowing communities to have control over how wildlife is managed in their area.

Example: In Namibia, communal conservancies allow local communities to manage wildlife, including revenues generated from tourism. These programs have reduced poaching and promoted coexistence by providing economic benefits tied to wildlife (Weaver & Petersen, 2008).

2. Compensation and Insurance Programs: Compensation programs are designed to reimburse individuals for losses caused by wildlife, such as the loss of livestock, crops, or infrastructure. These programs help to mitigate the financial burden placed on people who live in proximity to wildlife, reducing their motivation to harm animals in retaliation. Insurance schemes further reduce the financial risk to individuals by covering potential future damages caused by wildlife.

Example: In Kenya, a compensation scheme for farmers who lose livestock to lions has helped reduce retaliatory killings of the big cats, promoting greater tolerance of their presence (Gooden et al., 2009). Similarly, in India, crop insurance programs reimburse farmers for damage caused by elephants and other wildlife.

3. Use of Physical Barriers: Physical barriers, such as fences, walls, and trenches, can be effective in keeping wildlife out of areas where they might cause harm to people or property. Electrified fences, in particular, are widely used to protect farms and villages from large animals such as elephants and carnivores.

Example: In Botswana, electrified fences have been successful in reducing crop damage caused by elephants. These barriers prevent animals from entering agricultural lands, thereby reducing conflict (Graham et al., 2010).

Additionally, beehive fences in parts of Africa have been used to deter elephants, as elephants are naturally afraid of bees. This method not only protects crops but also generates honey as an additional source of income for farmers.

4. Land-Use Planning and Zoning: Effective land-use planning helps to designate areas for human activities and wildlife habitats, reducing the overlap where conflict is most likely to occur. This includes creating buffer zones, wildlife corridors, and designated grazing areas that limit human-wildlife interactions. Wildlife corridors are particularly important as they allow animals to migrate between habitats without crossing human-dominated landscapes.

Example: In Tanzania, the establishment of wildlife corridors between national parks has helped reduce human-wildlife conflict by allowing animals to move safely through designated areas rather than straying into farms or villages (Kideghesho, 2016).

5. Non-Lethal Deterrents: Non-lethal deterrents are tools or techniques that discourage wildlife from entering human spaces without causing them harm. These include using bright lights, loud noises, or chemical repellents to keep animals away from homes, farms, and villages. Such methods can be particularly useful in protecting crops from herbivores and livestock from predators.

Example: In Kenya, farmers have successfully used noise-making devices and lights to deter lions and hyenas from attacking their livestock. In India, chili and beehive fences have been used to deter elephants from raiding crops, providing a non-lethal and sustainable solution (King et al., 2011).

6. Education and Awareness Campaigns: Educating communities about wildlife behavior, conservation, and ways to prevent conflict is critical for fostering coexistence. Awareness campaigns can help people understand the ecological importance of wildlife, change negative perceptions of animals, and teach conflict prevention techniques.

Example: In Nepal, education campaigns in communities living near national parks have raised awareness about the importance of conserving endangered species like tigers and rhinos, while also teaching people how to avoid conflict with these animals (Thirgood et al., 2005).

7. Early Warning Systems: In areas where human-wildlife conflict is frequent, early warning systems can be implemented to alert people when wildlife is nearby. These systems use technology like GPS tracking, drones, or sensors to monitor animal movements and inform local communities in real-time, giving them enough time to take preventive measures.

Example: In Kenya, the Lion Guardians program uses GPS collars to track lions and alert herders when lions are approaching livestock. This system has reduced livestock losses and retaliatory killings of lions (Dolrenry et al., 2014).

8. Wildlife Relocation and Translocation: Relocating or translocating problematic wildlife to less conflict-prone areas can be an effective, albeit temporary, solution. Translocation is used in cases where individual animals, such as elephants or large carnivores, repeatedly come into conflict with humans.

Example: In India, elephants that have repeatedly raided crops are relocated to forest reserves where they are less likely to come into contact with humans, thereby reducing conflict in agricultural areas (Fernando et al., 2008).

9. Strengthening Law Enforcement and Anti-Poaching Efforts: Strengthening the enforcement of wildlife protection laws is essential in reducing illegal activities that contribute to human-wildlife conflict. Anti-poaching efforts not only protect endangered species but also help reduce conflict by maintaining healthy wildlife populations within designated conservation areas, rather than allowing them to roam freely into human settlements.

Example: In many African countries, increased patrols, better equipment, and stronger legal frameworks have helped reduce poaching, which indirectly reduces human-wildlife conflict by keeping animals within protected areas (Treves & Karanth, 2003).

10. Sustainable Livelihood Programs: Providing alternative sources of income to communities living near wildlife habitats is a long-term solution to reducing human-wildlife conflict. By reducing dependency on agriculture or livestock—which are often the focus of conflict—people can pursue more sustainable livelihoods that are less likely to put them in conflict with wildlife.

Example: In many African countries, eco-tourism programs provide employment opportunities for locals, allowing them to benefit from wildlife without the need for agriculture in conflict-prone areas. In some communities, sustainable harvesting of natural resources, such as honey or medicinal plants, provides an alternative to farming (Weaver & Petersen, 2008).

It is apparent that Human-wildlife conflict is a complex issue that requires a multi-faceted approach to resolve. The strategies discussed here—ranging from community-based conservation and compensation programs to the use of technology and non-lethal deterrents—are helping promote peaceful coexistence between humans and wildlife. These efforts not only protect human livelihoods but also ensure the long-term survival of wildlife populations. By implementing and refining these strategies, governments, conservation organizations, and communities can work together to reduce conflicts and support biodiversity conservation in areas where human and wildlife populations coexist.

References:

- Dolrenry, S., Hazzah, L., & Frank, L. (2014). Conservation and monitoring of a persecuted African lion population by Maasai warriors. Conservation Biology, 28(4), 1107–1117. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12244

- Fernando, P., Wikramanayake, E., Weerakoon, D., Jayasinghe, L. K. A., Gunawardena, M., & Janaka, H. K. (2008). Ranging behavior of the Asian elephant in Sri Lanka. Mammalian Biology, 73(1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2007.07.007

- Graham, M. D., Notter, B., Adams, W. M., Lee, P. C., & Ochieng, T. N. (2010). Patterns of crop-raiding by elephants in Laikipia, Kenya, and the management of human-elephant conflict. Conservation Biology, 24(4), 883–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01375.x

- Kideghesho, J. R. (2016). Co-existence between the traditional societies and wildlife in Western Serengeti, Tanzania: Its relevance in contemporary wildlife conservation efforts. Biodiversity and Conservation, 15(14), 3489–3511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-0827-6

- King, L. E., Douglas-Hamilton, I., & Vollrath, F. (2011). Beehive fences as effective deterrents for crop-raiding elephants: Field trials in northern Kenya. African Journal of Ecology, 49(4), 431–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2011.01275.x

- Gooden, B., French, K., Turner, P. J., & Downey, P. O. (2009). Impact threshold for an alien plant invader, Lantana camara L., on native plant communities. Biological Conservation, 142(11), 2631-2641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2009.06.012

- Thirgood, S., Woodroffe, R., & Rabinowitz, A. (2005). The impact of human-wildlife conflict on human lives and livelihoods. In R. Woodroffe, S. Thirgood, & A. Rabinowitz (Eds.), People and wildlife: Conflict or coexistence? (pp. 13-26). Cambridge University Press.

- Treves, A., & Karanth, K. U. (2003). Human-carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conservation Biology, 17(6), 1491–1499. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2003.00059.x

- Weaver, C. L., & Petersen, T. (2008). Namibia communal conservancies: A review of their successes and challenges. Parks, 18(2), 63-75.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College