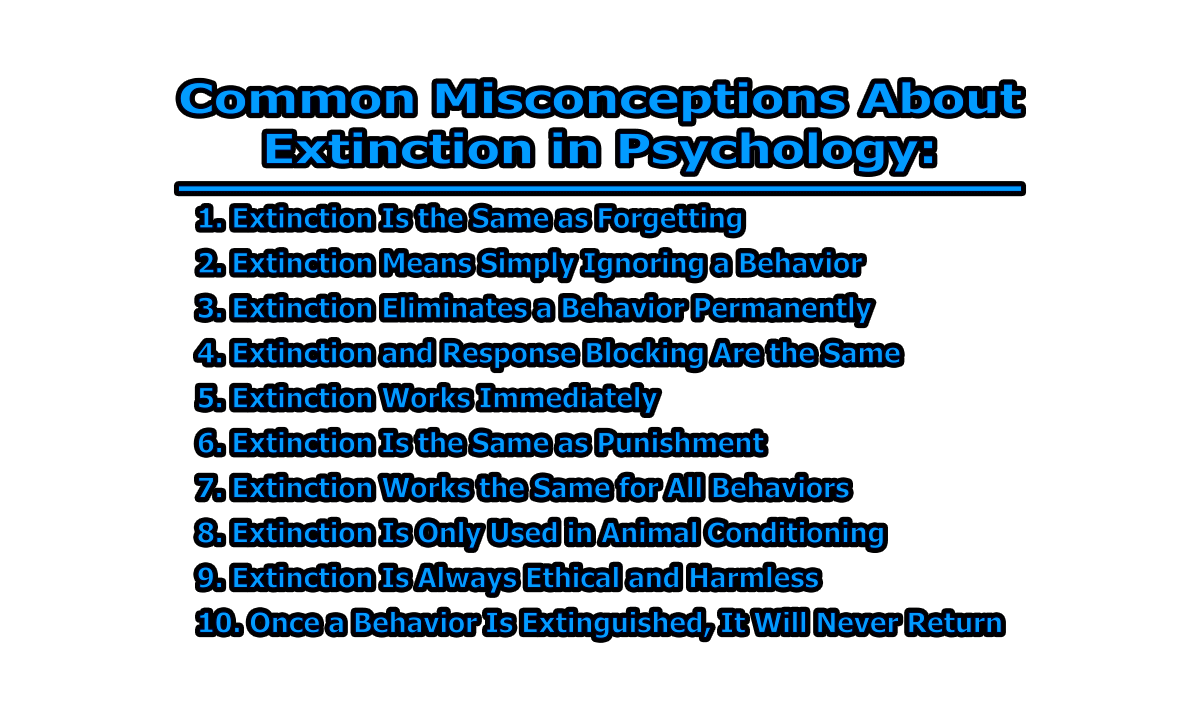

Common Misconceptions about Extinction in Psychology:

Extinction, in behavioral psychology, refers to the gradual weakening and disappearance of a conditioned response when reinforcement is no longer provided (Pavlov, 1927; Skinner, 1938). This principle plays a crucial role in various psychological interventions, including behavior modification, therapy, and education. Despite its significance, extinction is often misunderstood. Many misconceptions persist, leading to ineffective applications in real-world settings. This article aims to clarify 10 common misconceptions about extinction in psychology by examining research-based insights into this fundamental concept.

1. Extinction Is the Same as Forgetting:

One of the most widespread misconceptions about extinction is that it is simply forgetting a previously learned behavior. In reality, extinction does not erase a learned behavior from memory; rather, it suppresses the response through new learning (Bouton, 2004).

The Difference Between Extinction and Forgetting: Forgetting occurs when a learned behavior weakens over time due to a lack of retrieval or practice. It is a passive process, meaning that the individual does not actively engage in unlearning the behavior (Rescorla, 2004).

Extinction, on the other hand, is an active learning process where a behavior stops occurring because reinforcement is no longer provided (Pavlov, 1927; Skinner, 1938).

Spontaneous Recovery (A Key Indicator That Extinction Is Not Forgetting): A key reason extinction is not the same as forgetting is the phenomenon of spontaneous recovery. Spontaneous recovery occurs when an extinguished behavior unexpectedly reappears after some time, even though no reinforcement has been given (Bouton, 2002). This shows that the original learning is still present, but a new learning process (extinction) is temporarily suppressing it.

Example: Imagine a dog that has been conditioned to salivate at the sound of a bell because it was previously paired with food (classical conditioning). If the bell is repeatedly presented without food, the dog eventually stops salivating—this is extinction. However, after a break, the dog may unexpectedly start salivating again when it hears the bell. This is spontaneous recovery, proving that the learned association was never forgotten—it was merely suppressed (Rescorla, 2004).

2. Extinction Means Simply Ignoring a Behavior:

Another common myth is that extinction is nothing more than ignoring an unwanted behavior until it disappears. While ignoring can be one aspect of extinction, the process is much more complex. Extinction requires identifying and eliminating the reinforcer that maintains the behavior (Lerman & Iwata, 1996).

Why Ignoring Alone Is Not Always Effective: Ignoring only works if the behavior is being reinforced by attention (Iwata et al., 1994). However, many behaviors are maintained by different types of reinforcement, such as:

- Tangible reinforcement – A child may tantrum not just for attention but to gain access to a toy. Ignoring alone will not work if the toy continues to be given.

- Escape reinforcement – A student may act out to avoid doing homework. Ignoring the behavior will not work if the student is still allowed to skip homework.

- Sensory (automatic) reinforcement – Some behaviors, like nail-biting or self-stimulatory behaviors in autism, provide their own reinforcement. Ignoring has no effect because the behavior is self-rewarding.

The Need for Functional Behavior Analysis (FBA): Since ignoring alone is often insufficient, psychologists use a Functional Behavior Analysis (FBA) to determine what is reinforcing the behavior before applying extinction (Iwata et al., 1994).

Example: If a child repeatedly shouts in class, the teacher might assume the behavior is for attention and try ignoring it. However, if the child is actually shouting to avoid classwork, ignoring will not reduce the behavior. Instead, the teacher must ensure that the behavior no longer results in escape from work.

Thus, extinction is not just about withholding attention—it’s about identifying and removing all sources of reinforcement that maintain the behavior.

3. Extinction Eliminates a Behavior Permanently:

Many believe that once extinction occurs, the behavior is gone forever. In reality, behaviors that undergo extinction can spontaneously return due to three key effects:

A. Spontaneous Recovery: This occurs when an extinguished behavior re-emerges unexpectedly after a break (Bouton, 2002).

Example: A person who has successfully quit smoking may suddenly crave cigarettes weeks after stopping, even though they have not smoked.

B. Renewal Effect: This happens when a behavior returns in a new environment or context (Thomas et al., 2003).

Example: A child’s tantrums may stop at home (where extinction training occurred) but return at school, where the behavior was previously reinforced.

C. Reinstatement: This refers to the return of a previously extinguished behavior after a single exposure to the original reinforcer (Kalivas & O’Brien, 2008).

Example: A recovering alcoholic may relapse after one sip of alcohol because the taste reactivates old cravings.

Why Extinction Does Not Guarantee Permanent Behavior Change: Since extinction does not erase learning, behaviors can return in new situations or when the reinforcement is reintroduced. To increase long-term success, extinction is often combined with:

- Booster sessions – Additional extinction training to prevent spontaneous recovery.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) – Helps address thoughts that trigger relapses (Hofmann & Smits, 2008).

- Differential reinforcement – Encouraging an alternative, desirable behavior (Carr & Durand, 1985).

Thus, while extinction reduces behavior, it does not permanently eliminate learned associations. Instead, ongoing interventions are needed to maintain long-term behavior change.

4. Extinction and Response Blocking Are the Same:

Many people mistakenly believe that extinction and response blocking are identical techniques used to eliminate unwanted behaviors. However, while both are used in behavior modification, they are fundamentally different strategies with distinct mechanisms (Iwata et al., 1994).

What Is Response Blocking? Response blocking involves physically preventing a person from engaging in the behavior. This does not alter the behavior’s underlying reinforcement, but simply makes it impossible to perform. It is often used for self-injurious or dangerous behaviors, such as head-banging or severe self-biting in individuals with autism (Hanley et al., 2003).

Example: If a child persistently hits their head against the wall, caregivers may use protective headgear or physically block the behavior to prevent injury. However, if the behavior is maintained by automatic reinforcement (e.g., the sensory stimulation of head-banging), response blocking does not eliminate the underlying cause—it only prevents the act.

How Extinction Differs from Response Blocking: Unlike response blocking, extinction does not prevent the behavior itself—it removes the reinforcement that maintains it. For extinction to be effective, the behavior must still be allowed to occur, but it should no longer produce the expected reward (Iwata et al., 1994).

Example: A child who throws tantrums to get candy in a store may have their behavior extinguished if the parent consistently refuses to buy candy, leading to a decline in tantrums over time. If the parent simply restrains the child from throwing themselves on the floor (response blocking), the reinforcement (parental attention) may still be present, and the behavior could persist in other forms (e.g., screaming louder).

Why This Distinction Matters:

- Extinction alters the underlying learning process, while response blocking only prevents the behavior without changing reinforcement.

- Response blocking can sometimes lead to increased frustration and aggression if the person is still motivated to engage in the behavior (Lerman & Iwata, 1996).

- In clinical and educational settings, extinction is often preferred over response blocking because it focuses on reducing reinforcement rather than physically preventing actions.

Thus, while response blocking can be useful for immediate harm prevention, it should not be confused with extinction, which aims for long-term behavior change.

5. Extinction Works Immediately:

A common misconception is that behaviors immediately disappear once reinforcement is removed. In reality, extinction is a gradual process and often includes an initial increase in behavior before it declines (Craske et al., 2008).

The Extinction Burst (Why Behaviors Initially Increase): Extinction does not always produce an immediate decrease in behavior. In fact, many behaviors temporarily intensify when reinforcement is first removed. This phenomenon is called an extinction burst (Lerman & Iwata, 1996).

Example: Imagine a child who normally gets candy by whining at the grocery store. If the parent suddenly stops giving candy, the child may:

- Whine louder than before.

- Throw a tantrum in frustration.

- Try different strategies (e.g., grabbing candy off the shelf).

This temporary escalation is the child’s way of testing whether the behavior still works. If the parent stays consistent and does not give in, the behavior eventually declines.

Why Extinction Takes Time:

- The brain needs time to learn that the previous reinforcement no longer applies (Bouton, 2004).

- If a behavior was reinforced for a long time, it will take longer to extinguish (Rescorla, 2004).

- Intermittently reinforced behaviors (those that were rewarded inconsistently) are much more resistant to extinction than those reinforced every time (Smits et al., 2010).

Implications for Therapy and Education:

- Parents, therapists, and educators must be patient when using extinction-based interventions.

- If extinction bursts are mistaken for treatment failure, reinforcement might be reintroduced, making the behavior even stronger (Lerman & Iwata, 1996).

- Combining extinction with differential reinforcement of alternative behaviors (DRA) helps accelerate behavior reduction (Carr & Durand, 1985).

Thus, extinction is not an instant solution—it requires time, consistency, and reinforcement of positive replacement behaviors.

6. Extinction Is the Same as Punishment:

Many assume that extinction is just another form of punishment, but these are fundamentally different concepts with different effects on behavior (Iwata et al., 1994).

Key Differences Between Extinction and Punishment:

| Feature | Extinction | Punishment |

| Definition | Removing reinforcement to weaken a behavior | Adding an aversive consequence to reduce behavior |

| Process | Gradual decline in behavior | Immediate suppression of behavior |

| Emotional Impact | Often produces frustration (extinction burst) | Can lead to fear, avoidance, or aggression |

| Effectiveness | Works best when combined with reinforcement of alternative behaviors | Can lead to short-term compliance but may not change long-term behavior |

Why Punishment Is Not the Same as Extinction:

- Punishment involves adding an unpleasant consequence (e.g., scolding, timeout, physical reprimands).

- Extinction involves removing reinforcement without introducing punishment.

- Punishment may suppress behavior temporarily, but does not teach alternative behaviors (Sidman, 1989).

Example:

- A child who talks out of turn in class may stop if the teacher yells at them (punishment). However, they might continue the behavior when the teacher is not watching or develop negative emotions toward school.

- If the teacher ignores the talking out (extinction) and reinforces hand-raising instead, the child learns to seek attention in an appropriate way.

Why Extinction Is Often Preferred Over Punishment:

- Research shows that extinction produces more lasting behavior change than punishment (Iwata et al., 1994).

- Punishment can cause negative emotional effects such as aggression, anxiety, or avoidance of the punishing person (Skinner, 1953).

- Extinction is more ethical and effective when paired with reinforcement of desirable behaviors.

Thus, extinction is not the same as punishment—it focuses on removing reinforcement, while punishment introduces negative consequences. Proper behavior management strategies favor extinction with positive reinforcement over punishment-based approaches.

7. Extinction Works the Same for All Behaviors:

Many believe that extinction affects all behaviors equally, but research shows that some behaviors are more resistant to extinction than others (Rescorla, 2004). The effectiveness of extinction depends on several factors, including:

A. The History of Reinforcement:

- Behaviors that were reinforced for a long time take longer to extinguish (Nevin & Grace, 2000).

- If a behavior has been rewarded intermittently (rather than consistently), it is more resistant to extinction (Bouton, 2002).

- Example: A child who was given candy every time they cried may stop crying faster when extinction is applied than a child who received candy only sometimes.

B. The Type of Reinforcement Maintaining the Behavior: Some behaviors are maintained by strong reinforcement contingencies, such as:

- Escape reinforcement – If a behavior helps someone avoid an unpleasant task (e.g., a child tantrums to escape homework), it can be harder to extinguish (Iwata et al., 1994).

- Sensory reinforcement – Behaviors that provide their own internal reward (e.g., rocking or hand-flapping in autism) are more resistant to extinction because no external reinforcement needs to be removed (Hanley et al., 2003).

C. The Emotional Impact of Extinction:

- Some behaviors are associated with strong emotions, making extinction more difficult.

- Example: Fear-based behaviors, such as avoidance in phobias, may not fully extinguish if the fear response is too strong (Craske et al., 2008).

Implications: Since extinction does not work the same for all behaviors, behavior analysts must:

- Analyze reinforcement history before applying extinction.

- Use extinction alongside alternative reinforcements to make behavior change more effective.

- Recognize when extinction alone is not enough and supplement with cognitive or pharmacological interventions.

Thus, extinction is not a one-size-fits-all process—its success depends on reinforcement history, the type of behavior, and emotional factors.

8. Extinction Is Only Used in Animal Conditioning:

Some assume extinction is mainly used in classical conditioning studies with animals, like Pavlov’s dogs or Skinner’s pigeons. However, extinction is widely applied in human psychology, including therapy, education, and addiction treatment (Bouton, 2004).

Extinction in Human Applications:

A. Extinction in Exposure Therapy: In exposure therapy, individuals with anxiety disorders repeatedly face their fears without negative consequences, leading to extinction of the fear response (Craske et al., 2008).

Example: A person with a spider phobia may undergo gradual exposure to spiders in a controlled environment to weaken the fear response.

B. Extinction in Parenting and Education:

- Parents use extinction to reduce attention-seeking behaviors by removing reinforcement (e.g., ignoring tantrums) (Lerman & Iwata, 1996).

- Teachers use extinction when they stop responding to disruptive behaviors that were previously reinforced by attention (Reeve et al., 2007).

C. Extinction in Addiction Treatment: Cue-exposure therapy (CET) exposes individuals to drug-related cues (e.g., the sight of alcohol) without allowing drug use, leading to extinction of cravings (Marchant et al., 2019).

Example: A former smoker may undergo repeated exposure to the smell of cigarettes without actually smoking to weaken their craving response.

Why This Misconception Exists:

- Many early extinction studies focused on animal learning (Pavlov, 1927; Skinner, 1938), leading people to associate extinction with basic animal conditioning.

- However, modern psychological research has expanded extinction’s role in treating human behaviors, especially in mental health, education, and addiction recovery.

Thus, extinction is not just for animals—it is a fundamental process in human learning and behavior modification.

9. Extinction Is Always Ethical and Harmless:

Some assume extinction is always a safe and ethical approach. While it is generally considered more ethical than punishment-based methods, it can cause negative side effects if not implemented correctly (Lerman & Iwata, 1996).

A. The Extinction Burst and Emotional Reactions:

- When reinforcement is removed, individuals often experience an extinction burst—a temporary increase in the behavior before it decreases (Iwata et al., 1994).

- This can lead to frustration, aggression, and emotional distress (Hanley et al., 2003).

- Example: A child whose tantrums were previously reinforced with attention may initially scream louder and longer when the behavior is ignored.

B. Potential Ethical Concerns in Therapy:

- If extinction is used in a way that causes distress without providing alternative coping strategies, it can be psychologically harmful.

- Example: In treating PTSD, exposure therapy (which relies on extinction) must be carefully controlled to avoid retraumatization (Craske et al., 2008).

C. When Extinction May Be Inappropriate:

- For self-injurious behaviors – Ignoring dangerous behaviors (e.g., head-banging, self-hitting) without providing a safer alternative can be unethical (Hanley et al., 2003).

- For individuals with communication challenges – If a child with autism engages in problem behaviors to communicate needs, simply removing reinforcement without teaching an alternative communication method can increase distress (Carr & Durand, 1985).

Ethical Guidelines for Using Extinction:

- Extinction should always be paired with reinforcement of desirable behaviors to reduce frustration and distress.

- Alternative communication strategies should be provided when reducing problem behaviors in individuals with developmental disabilities.

- In high-risk cases (e.g., self-injury), extinction should be used cautiously and combined with protective interventions (Hanley et al., 2003).

Thus, while extinction is a valuable tool, it is not always harmless—it must be applied ethically and with consideration for individual needs.

10. Once a Behavior Is Extinguished, It Will Never Return:

A common misconception about extinction is that once a behavior has been extinguished, it is permanently eliminated. However, research has shown that extinguished behaviors can return under specific conditions, including spontaneous recovery, renewal, and reinstatement (Bouton, 2002).

A. Spontaneous Recovery (The Behavior Can Reappear Over Time): Spontaneous recovery occurs when a previously extinguished behavior suddenly reappears after a period of time without further reinforcement (Pavlov, 1927).

Example: A child who no longer throws tantrums for candy may unexpectedly have a tantrum weeks later, even though reinforcement (candy) was removed.

Key Insight:

- Just because a behavior disappears does not mean it is permanently erased from memory.

- Spontaneous recovery suggests that learning is not unlearned, but rather inhibited, and can re-emerge.

B. Renewal Effect (The Behavior Returns in a Different Context): Renewal happens when a behavior that was extinguished in one setting returns in a different environment (Crombag & Shaham, 2002).

Example: A person recovering from smoking cravings may feel fine in a rehab facility but experience renewed cravings when they return home, where they used to smoke.

Key Insight: This suggests that extinction is context-dependent—the behavior is suppressed in the setting where extinction occurred but may reappear in new environments.

C. Reinstatement (A Single Exposure to the Reinforcer Can Bring Back the Behavior): Reinstatement occurs when a behavior that was previously extinguished returns after a single exposure to the original reinforcer (Kalivas & O’Brien, 2008).

Example: A person recovering from alcohol addiction may experience a single drink triggering full relapse, even after months of sobriety.

Key Insight:

- Extinction does not erase previous learning—it only weakens it.

- A single reminder of the past reinforcement can cause a relapse in behavior.

How to Prevent Relapse After Extinction: Since extinguished behaviors can return, psychologists use several strategies to reduce the likelihood of relapse:

- Multiple extinction sessions – Repeated exposure to extinction trials can ]help weaken spontaneous recovery (Bouton, 2004).

- Extinction in multiple contexts – Practicing extinction in different environments helps prevent the renewal effect (Craske et al., 2008).

- Using alternative reinforcement – Reinforcing new behaviors reduces the likelihood of reinstatement (Lerman & Iwata, 1996).

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) – Helps individuals recognize and manage triggers that could reactivate old behaviors (Smits et al., 2010).

In conclusion, extinction is a crucial behavioral principle, but misconceptions often hinder its effective application. By clarifying that extinction is not the same as forgetting, punishment, or response blocking, and by recognizing factors like spontaneous recovery, extinction bursts, and the need for reinforcement alternatives, practitioners can apply extinction strategies more effectively. Understanding these principles can lead to more successful behavior modification outcomes in clinical, educational, and therapeutic settings.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Does extinction mean a behavior is permanently erased?

No, extinction does not permanently erase a behavior. Instead, it weakens the connection between a behavior and its reinforcement. The behavior may return under certain conditions, such as after a period of time or in a different setting.

Is extinction the same as punishment?

No, extinction and punishment are different. Extinction involves removing the reinforcement that maintains a behavior, leading to its gradual decrease. Punishment, on the other hand, introduces an unpleasant consequence or removes a positive stimulus to discourage behavior.

Does extinction work instantly?

No, extinction is a gradual process. In fact, the behavior might temporarily increase in intensity or frequency before it starts to fade. This temporary spike in behavior is known as an extinction burst.

Does extinction work the same way in all environments?

No, extinction is influenced by context. A behavior that is eliminated in one environment may reappear in another. For example, someone overcoming a habit in a therapy setting might still struggle when returning to their usual surroundings.

Is extinction only used for stopping bad behavior?

No, extinction is also used in therapy, education, and behavior modification. It helps individuals unlearn certain responses, such as phobias, cravings, or compulsive behaviors, making it a valuable tool beyond just eliminating negative actions.

Will a behavior always disappear if reinforcement is removed?

Not necessarily. If a behavior has been reinforced inconsistently over time, it may persist even after reinforcement stops. This is because behaviors reinforced unpredictably tend to be more resistant to extinction.

Can extinction be harmful?

In some cases, yes. If not handled properly, extinction can lead to frustration, aggression, or even an initial increase in unwanted behavior. That’s why it is often combined with other strategies, like rewarding alternative behaviors, to ensure a smoother transition.

Does extinction work for all types of behaviors?

No, some behaviors are harder to extinguish, especially those linked to biological needs, strong emotions, or addiction. In such cases, extinction is more effective when combined with other treatments like therapy or medication.

Can extinction be reversed?

Yes, an extinguished behavior can return under certain conditions. This can happen if the individual is exposed to the original reinforcement again, encounters a similar environment, or if enough time passes since extinction occurred.

Is extinction only relevant to psychology?

No, extinction principles are widely used in various fields, including education, business, animal training, and artificial intelligence. For example, companies use extinction techniques in advertising to change consumer behavior, and AI systems adjust their responses based on feedback.

References:

- Bouton, M. E. (2002). Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: Sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biological Psychiatry, 52(10), 976-986. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01546-9

- Bouton, M. E. (2004). Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning & Memory, 11(5), 485-494. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.78804

- Carr, E. G., & Durand, V. M. (1985). Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18(2), 111-126. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111

- Conklin, C. A., & Tiffany, S. T. (2002). Applying extinction to drug cues: Clinical relevance and methodological issues. Addiction, 97(2), 155-167. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x

- Craske, M. G., Kircanski, K., Zelikowsky, M., Mystkowski, J., Chowdhury, N., & Baker, A. (2008). Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(1), 5-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.003

- Crombag, H. S., & Shaham, Y. (2002). Renewal of drug seeking by contextual cues after prolonged extinction in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience, 116(1), 169-173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7044.116.1.169

- Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M. F., Slifer, K. J., Bauman, K. E., & Richman, G. S. (1994). Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(2), 197-209. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197

- Kalivas, P. W., & O’Brien, C. (2008). Drug addiction as a pathology of staged neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(1), 166-180. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301564

- Lerman, D. C., & Iwata, B. A. (1996). Developing a technology for the use of extinction in clinical settings: An examination of basic and applied research. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29(3), 345-382. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1996.29-345

- Otto, M. W., McHugh, R. K., & Kantak, K. M. (2010). Combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: Medication effects, glucocorticoids, and attenuated treatment outcomes. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(2), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01198.x

- Marchant, N.J., Campbell, E.J., Pelloux, Y. et al. (2019). Context-induced relapse after extinction versus punishment: similarities and differences. Psychopharmacology, 236, 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-4929-1

- Nevin, J. A., & Grace, R. C. (2000). Behavioral momentum and the law of effect. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23(1), 73-90.

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Oxford University Press.

- Hanley GP, Iwata BA, McCord BE. Functional analysis of problem behavior: a review. J Appl Behav Anal. 2003 Summer;36(2):147-85. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147. PMID: 12858983; PMCID: PMC1284431.

- Smits, J. A. J., Reese, H. E., & Powers, M. B. (2010). Combined cognitive behavioral and pharmacologic treatment strategies: Current status and future directions (M. W. Otto, Ed.). In M. W. Otto & S. G. Hofmann (Eds.), Avoiding treatment failures in the anxiety disorders (pp. 67–81). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0612-0_5

- Reeve, S. A., Casey, L. B., & Anderson, C. M. (2007). Functional analysis and treatment of problem behavior in school settings. Journal of Behavioral Education, 16(1), 33-54.

- Rescorla, R. A. (2004). Spontaneous recovery. Learning & Memory, 11(5), 501-509. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.77504

- Sidman M (1989). Avoidance at Columbia. The Behavior Analyst, 12(2), 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03392496

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Appleton-Century.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College