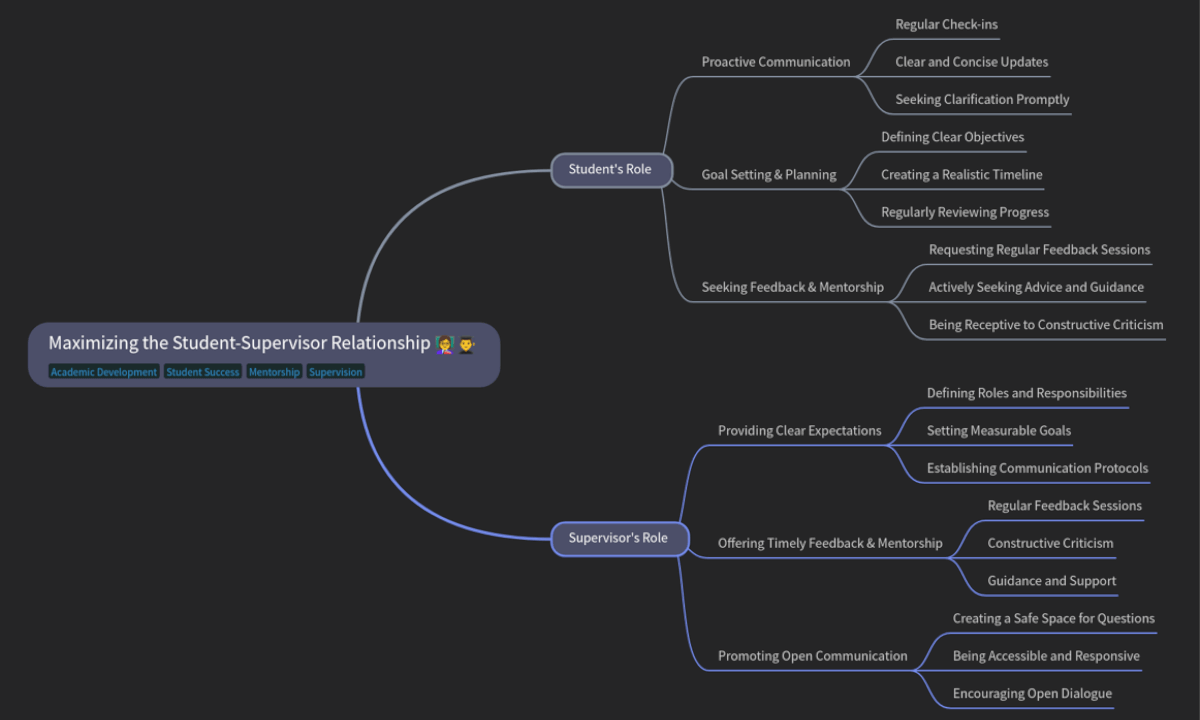

Maximizing the Student-Supervisor Relationship:

The student-supervisor relationship plays a significant role in determining the success of academic and research endeavors. A well-managed relationship fosters intellectual growth, enhances productivity, and supports academic achievement. This article explores the statement “Maximizing the Student-Supervisor Relationship” by examining the roles and responsibilities of both students and supervisors.

1. Student’s Role:

1.1 Proactive Communication: Effective communication forms the cornerstone of a successful student-supervisor relationship. Students must take responsibility for initiating and maintaining meaningful dialogue with their supervisors.

- Regular Check-ins: Frequent meetings with supervisors are essential for ensuring steady progress and resolving potential issues early. According to Lee (2008), regular interactions foster trust, motivation, and intellectual growth. Students should schedule these meetings proactively, come prepared with specific discussion points, and set clear agendas. Documentation of each meeting’s outcomes through concise summaries can also serve as a reference for future discussions.

- Clear and Concise Updates: Providing precise and structured updates allows supervisors to give relevant feedback (Manathunga & Goozée, 2007). Updates should include research milestones achieved, challenges encountered, and strategies for overcoming these challenges. Written reports or email summaries after meetings help maintain clarity and ensure mutual understanding regarding progress and future objectives.

- Seeking Clarification Promptly: Timely clarification is crucial to avoid misunderstandings that may derail the research process. Gatfield (2005) emphasizes that students who ask questions promptly are better able to maintain focus and achieve their research goals. This proactive approach requires students to seek feedback on ambiguous aspects of their work and confirm understanding of complex research methodologies and supervisor expectations.

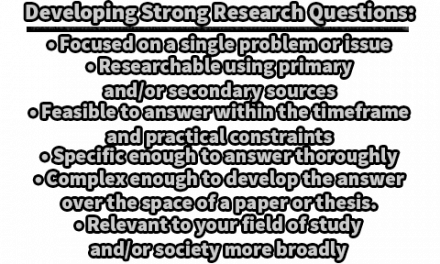

1.2 Goal Setting & Planning: Clear goals and effective planning are essential for academic success. Students should adopt structured strategies to define their objectives, create actionable timelines, and monitor progress consistently.

- Defining Clear Objectives: Students must establish well-defined research goals that align with the broader objectives of their academic programs. Phillips and Pugh (2010) highlight that clear objectives contribute significantly to higher completion rates. Goals should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), providing a clear sense of direction and purpose.

- Creating a Realistic Timeline: A realistic timeline breaks the research project into manageable tasks with specific deadlines. Wisker (2005) suggests including buffer periods to accommodate unforeseen challenges, ensuring flexibility without compromising overall deadlines. Digital tools like Gantt charts can help visualize the timeline, making it easier to adjust plans when necessary.

- Regularly Reviewing Progress: Consistent progress reviews are vital for staying aligned with research objectives. Grant (2003) notes that reflective self-assessments enable students to make necessary adjustments, thereby enhancing research quality. Tools such as progress journals or reflective logs can help track milestones, analyze setbacks, and plan corrective actions.

1.3 Seeking Feedback & Mentorship: Constructive feedback and mentorship are fundamental to academic development. Students should take an active role in seeking guidance and responding positively to criticism.

- Requesting Regular Feedback Sessions: Lovitts (2001) found that students who consistently receive feedback are more likely to produce high-quality research. Feedback sessions should be strategically scheduled at key milestones to refine research direction and methodologies. Preparation for these sessions, including presenting key findings and areas of concern, ensures focused and productive discussions.

- Actively Seeking Advice and Guidance: Successful students leverage their supervisor’s expertise and professional networks. Ives and Rowley (2005) argue that mentorship extends beyond immediate supervision to include participation in seminars, workshops, and academic conferences. Engaging with broader academic communities enhances exposure, fosters collaborations, and opens new research avenues.

- Being Receptive to Constructive Criticism: Constructive criticism is a catalyst for academic growth. Wright and Cochrane (2000) found that receptiveness to feedback strongly correlates with successful thesis completion. Students should approach criticism objectively, using it to refine arguments, improve methodologies, and strengthen overall research quality. Viewing feedback as an opportunity rather than a setback is essential for long-term success.

2. Supervisor’s Role:

2.1 Providing Clear Expectations: Supervisors are responsible for establishing a solid foundation by clearly defining roles, responsibilities, and objectives. Effective guidance from the outset significantly enhances the student’s research experience and outcomes.

- Defining Clear Roles and Responsibilities: Supervisors must articulate their expectations regarding the student’s responsibilities, research activities, and timelines. According to Kamler and Thomson (2006), clarity in these areas minimizes misunderstandings and reduces the likelihood of conflicts. By providing comprehensive project outlines and specifying deliverables, supervisors help students navigate the research process with confidence.

- Setting Measurable Goals: Setting achievable and measurable goals ensures that students have a clear trajectory for their research. Boud and Lee (2005) emphasize that well-defined goals improve motivation and progress. Supervisors should collaborate with students to develop short-term and long-term objectives using the SMART framework (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound). Regular evaluations of these goals enable timely adjustments and ensure alignment with broader academic requirements.

- Establishing Communication Protocols: Effective communication protocols prevent misunderstandings and ensure consistent interactions. Deuchar (2008) suggests that supervisors should define preferred communication methods (e.g., email, virtual meetings) and establish regular meeting schedules. Clear guidelines on response times, feedback procedures, and availability set professional boundaries and expectations, creating a structured and supportive environment.

2.2 Offering Timely Feedback & Mentorship: Supervisors play a pivotal role in providing feedback and mentorship that fosters academic growth and research excellence.

- Regular Feedback Sessions: Timely feedback is crucial for refining research methodologies and arguments. Halse and Malfroy (2010) assert that feedback delivered at key project stages enhances academic quality and supports timely completion. Supervisors should schedule feedback sessions that align with major milestones, ensuring that the feedback provided is actionable and constructive.

- Constructive Criticism: Effective feedback balances praise with constructive criticism. Pearson and Brew (2002) highlight that feedback should be specific, focused on content rather than personal attributes, and delivered in a manner that motivates improvement. Constructive criticism enables students to refine their research while developing resilience and critical thinking skills.

- Guidance and Support: Mentorship extends beyond technical guidance to include professional and personal development. Grant (2003) notes that supervisors who actively mentor students contribute to higher completion rates and greater research satisfaction. Supervisors can support students by recommending relevant literature, facilitating networking opportunities, and providing career advice, thereby enriching the overall academic experience.

2.3 Promoting Open Communication: Open communication builds trust and encourages intellectual exploration. Supervisors must foster an environment where students feel comfortable sharing ideas, asking questions, and expressing concerns.

- Creating a Safe Space for Questions: Supervisors should encourage students to voice their uncertainties without fear of judgment. Wisker (2005) suggests that creating an open and respectful atmosphere helps students engage more deeply with their research. This approach not only builds confidence but also fosters a culture of curiosity and learning.

- Being Accessible and Responsive: Accessibility is a critical factor in effective supervision. According to Manathunga and Goozée (2007), supervisors who are responsive and available significantly influence student satisfaction and progress. Supervisors should establish clear guidelines regarding availability and ensure timely responses to student inquiries.

- Encouraging Open Dialogue: Encouraging open and honest dialogue ensures that both parties can address issues proactively. Deuchar (2008) emphasizes that open dialogue helps prevent conflicts and supports the continuous alignment of research goals. Regular, informal check-ins can supplement formal meetings, providing opportunities to discuss progress, challenges, and future plans.

It is apparent that maximizing the student-supervisor relationship requires proactive engagement from both parties. Students should communicate effectively, set clear goals, and embrace feedback. Supervisors must provide clear expectations, timely mentorship, and foster open communication. By fulfilling these roles, the relationship becomes a catalyst for academic success and professional growth.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

How often should students meet with their supervisors?

Regular meetings, ideally every two to four weeks, are recommended. The frequency may vary depending on the research stage and project complexity.

What should students prepare before a supervision meeting?

Students should prepare an agenda outlining progress updates, questions, challenges, and discussion topics. Providing written summaries can help maintain clarity and focus during meetings.

How can supervisors effectively manage multiple students?

Supervisors should establish clear communication protocols, set individual and group meeting schedules, and prioritize time based on project urgency and complexity.

What is the best way for students to receive feedback?

Students should actively seek feedback, remain open to constructive criticism, and view feedback as an opportunity for growth and improvement.

How can supervisors promote independent research skills?

Supervisors can promote independence by gradually reducing direct guidance, encouraging critical thinking, and providing opportunities for students to present their work in seminars and conferences.

What can students do if conflicts arise?

Addressing issues early by discussing concerns openly with supervisors is crucial. If necessary, involving a third party, such as a departmental advisor, can help mediate and resolve conflicts.

How do cultural differences impact the student-supervisor relationship?

Cultural awareness and sensitivity are essential. Both supervisors and students should discuss expectations, communication styles, and academic norms to build mutual understanding.

What role does mentorship play beyond supervision?

Mentorship extends beyond research guidance and includes career advice, networking opportunities, and personal development support. Strong mentorship enhances research satisfaction and academic success.

How can students stay motivated during long research projects?

Setting short-term goals, celebrating milestones, and seeking peer support are effective ways to stay motivated. Supervisors can help by recognizing achievements and providing ongoing encouragement.

What are the key qualities of a successful student-supervisor relationship?

Trust, respect, open communication, and mutual commitment to research objectives are fundamental for building a successful partnership.

References:

- Boud, D., & Lee, A. (2005). Peer learning as pedagogic discourse for research education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(5), 501-516. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500249138

- Delamont, S., Atkinson, P., & Parry, O. (1998). Supervising the PhD: A guide to success. Open University Press. ISBN-0-335-19516-4

- Deuchar, R. (2008). Facilitator, director, or critical friend? Contradiction and congruence in doctoral supervision styles. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(4), 489-500. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802193905

- Evans, L., & Stevenson, H. (2011). The work of teacher educators: Understanding academic work in professional fields. Higher Education, 61(3), 395-411.

- Gatfield, T. (2005). An investigation into PhD supervisory management styles: Development of a dynamic conceptual model and its managerial implications. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 27(3), 311-325. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800500283585

- Grant, B. (2003). Mapping the pleasures and risks of supervision. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 24(2), 175-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596300303042

- Gurr, G. M. (2001). Negotiating the “Rackety Bridge” — a dynamic model for aligning supervisory style with research student development. Higher Education Research & Development, 20(1), 81-92.

- Hockey, J. (1997). A complex craft: United Kingdom PhD supervision in the social sciences. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 2(1), 45-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596749700200004

- Halse, C., & Malfroy, J. (2010). Retheorizing Doctorial Supervision as Professional Work. Studies in Higher Education, 35, 79-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075070902906798

- Ives, G., & Rowley, G. (2005). Supervisor selection or allocation and continuity of supervision: PhD students’ progress and outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, 30(5), 535-555. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500249161

- Kam, B. H. (1997). Style and quality in research supervision: The supervisor dependency factor. Springer: Higher Education.

- Kamler, B., & Thomson, P. (2006). Helping doctoral students write: Pedagogies for supervision. Routledge.

- Lee, A. (2008). How are doctoral students supervised? Concepts of doctoral research supervision. Studies in Higher Education, 33(3), 267-281. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802049202

- Lovitts, B. E. (2001). Leaving the ivory tower: The causes and consequences of departure from doctoral study. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Manathunga, C., & Goozée, J. (2007). Challenging the Dual Assumption of the “Always/Already” Autonomous Student and Effective Supervisor. Teaching in Higher Education, 12, 309-322. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562510701278658

- McAlpine, L., & Amundsen, C. (2009). Doctoral education: Research-based strategies for doctoral students, supervisors and administrators. Springer.

- Pearson, M., & Brew, A. (2002). Research training and supervision development. Studies in Higher Education, 27(2), 135-150. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070220119986c

- Phillips, E. M., & Pugh, D. S. (2010). How to get a PhD: A handbook for students and their supervisors. Open University Press.

- Wright, T., & Cochrane, R. (2000). Factors influencing successful submission of PhD theses. Studies in Higher Education, 25(2), 181-195. https://doi.org/10.1080/713696139

- Wisker, G. (2005). The good supervisor: Supervising postgraduate and undergraduate research for doctoral theses and dissertations. Palgrave Macmillan.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College