Basic Understanding of Debate:

Debate is more than just two people arguing their opinions — it’s a structured exchange of ideas where participants present evidence, challenge opposing viewpoints, and persuade an audience or panel through reasoned arguments. At its core, debate is about critical thinking, effective communication, and respectful disagreement. It encourages participants to look at an issue from multiple perspectives, build logical cases, and respond thoughtfully to counterarguments. Whether it takes place in a classroom, a public forum, or a competitive setting, debate helps sharpen one’s ability to analyze information, think on their feet, and articulate ideas clearly. Beyond winning or losing, the true value of debate lies in learning to engage with others’ viewpoints while confidently expressing your own. In the rest of this article, we will explore the basic understanding of debate.

What is Debate?

There are several experts who offer thoughtful definitions of debate. Among them are:

Encyclopaedia Britannica describes debate as a formal, oral confrontation featuring two opposing sides who present arguments under a structured format, including initial contentions and rebuttals moderated by a neutral party.

Merriam-Webster defines debate as a regulated discussion of a proposition between matched sides, or alternatively as contention by words or arguments, highlighting its dual nature as both formal and argumentative.

EBSCO Research Starters (Campbell, 2024) frames debate as a formal discussion format governed by specific rules. Participants present arguments in favor of or against a motion, relying on public speaking and performance to persuasively communicate their positions while avoiding personal attacks.

Wikipedia (Debate article) emphasizes that debate is a formal discourse, often involving opposing viewpoints in settings such as public forums or academic institutions. It notes the historical roots of debate and how modern formats stress logic, factual accuracy, and presentation.

Sheffield Hallam University presents debate as an educational method: a teaching approach where students research and defend opposing views on a topic, promoting critical thinking, structured argumentation, and effective communication.

From the above definitions, we can conclude that debate is best understood as a formal, structured exchange of ideas where opposing sides present arguments, often regulated by rules, with the goal of persuading or clarifying positions. Its value lies not only in the contest of ideas but also in stimulating critical thinking, sharpening communication, and facilitating deeper understanding.

The Nature of Debates:

At its core, a debate is much more than just two sides arguing over a topic—it is a structured, purposeful exchange of ideas in which individuals or teams present opposing viewpoints on a clearly defined subject. The central aim of a debate is not always to reach a consensus or “win” over the other side. Instead, its primary purpose is to explore all dimensions of an issue, allowing participants and audiences alike to examine the topic from multiple perspectives. By doing so, debates promote critical thinking, sharpen analytical skills, and encourage informed decision-making.

What makes debates distinct from casual discussions is their structured nature. They operate within an agreed set of rules that are designed to ensure fairness, balance, and respect between all parties. These rules may include strict time limits for presenting arguments, responding to opponents, and delivering closing statements. Time management is crucial—participants must express their ideas clearly and persuasively within the allotted window, which adds a strategic layer to their preparation and delivery.

Another defining element of debates is the role of the moderator. This person is responsible for maintaining order, keeping the discussion on track, and ensuring that the agreed-upon rules are followed. A skilled moderator will step in if the conversation veers off-topic, if time limits are ignored, or if interactions become disrespectful. The presence of a moderator helps guarantee that both sides have an equal opportunity to present their case without being interrupted or overshadowed.

Debates can take place in a wide range of settings—from academic competitions and classroom activities to political campaigns, community forums, and media broadcasts. Regardless of context, they share the same core principles: respect for differing opinions, reliance on reason and evidence, and a commitment to exploring the topic in depth.

Eventually, the nature of a debate lies in its ability to transform disagreement into a constructive and enlightening process. Rather than simply seeking to “defeat” an opponent, a successful debate challenges everyone involved—speakers and listeners alike—to question assumptions, consider alternative viewpoints, and arrive at a more nuanced understanding of the issue at hand.

Benefits of Debate:

Debating is far more than a competitive exercise—it is a transformative learning experience that equips students with skills and qualities they can carry into every stage of life. From the classroom to the workplace, from community leadership to personal relationships, the benefits of learning to debate and speak in public are both immediate and long-lasting.

One of the most significant advantages of debate is the development of strong oral and written communication skills. Students learn not only how to speak clearly and persuasively, but also how to organize their thoughts in writing with precision and impact. This ability to express ideas effectively is valuable in academic essays, professional correspondence, and any setting that demands clear communication.

Debate also sharpens critical thinking. It teaches students to evaluate arguments, identify logical flaws, weigh evidence, and consider alternative perspectives before drawing conclusions. This analytical mindset is an asset in problem-solving, decision-making, and lifelong learning.

Another benefit is the mastery of research, organization, and presentation tools. Successful debaters know how to locate credible sources, extract relevant information, and arrange their findings in a structured, compelling way. They also develop the skills to present their arguments confidently, using tone, body language, and visual aids to engage their audience.

Importantly, debate helps students overcome the fear of public speaking. Many enter the activity feeling nervous or self-conscious, but through practice and constructive feedback, they learn to manage anxiety, project their voice, and maintain composure in front of an audience. This transformation often leads to a newfound enthusiasm for participating in class discussions and other public forums.

Debating also nurtures personal qualities and interpersonal skills that shape character and influence future success:

- Confidence – Building trust in one’s own abilities and cultivating the courage to take intellectual risks.

- Curiosity – Developing a love for exploration and discovery, fueled by effective research and questioning techniques.

- Critical Thinking – Seeing the world through an analytical lens, able to separate fact from opinion and evaluate complex issues.

- Communication – Mastering respectful and engaging dialogue, even when disagreeing with others.

- Control – Gaining composure under pressure, transforming nervousness into focused energy.

- Creativity – Thinking beyond conventional solutions, crafting innovative arguments, and adapting ideas to different contexts.

- Camaraderie – Forming connections with peers who share similar interests, and enjoying the spirit of healthy competition.

- Leadership – Learning to take initiative, delegate tasks, inspire others, and manage group efforts toward common goals.

Ultimately, the benefits of debate extend well beyond tournaments or classroom grades. It shapes students into confident, informed, and articulate individuals who can think independently, engage constructively with diverse perspectives, and lead with integrity. These qualities remain relevant in every walk of life, making debate one of the most valuable educational experiences a student can pursue.

Forms of Debates:

Debate, as a structured exchange of ideas, is not confined to one single format. Over time, educators, policymakers, and public speakers have developed a variety of debate forms to meet different purposes, audiences, and contexts. At its broadest level, debate can be categorized into two main types: informal debates and formal debates—each with its own value and style.

1. Informal Debates: Informal debates are the kinds of discussions most people have without even realizing they are engaging in a form of debate. They often occur spontaneously—around the dinner table, during a classroom discussion, or while talking with friends at a café. The focus here is not on “winning” or adhering to rigid rules, but on sharing perspectives and exploring ideas.

- There is no assigned time limit or strict structure.

- Participants can interrupt politely, ask questions as they arise, and introduce new angles freely.

- They are valuable for building confidence in speaking, practicing active listening, and testing ideas in a relaxed environment.

For example, a group of classmates discussing whether social media does more harm than good might exchange views, cite personal experiences, and even disagree strongly—but without a formal moderator or scoring system. These conversations are excellent stepping stones for developing the skills that formal debate demands.

2. Formal Debates: Formal debates are more structured, rule-based, and often competitive. They usually take place in academic institutions, political arenas, or public forums. In this setting, participants are divided into two sides:

- The affirmative (supporting the resolution)

- The negative (opposing the resolution)

Each side is given specific speaking times, follows a predetermined sequence (opening statements, rebuttals, cross-examinations, and closing arguments), and is evaluated on clarity, logic, evidence, and persuasiveness.

Formal debates aim to test a participant’s ability to:

- Organize ideas clearly and persuasively

- Use credible evidence to support claims

- Think quickly under pressure

- Respond respectfully yet effectively to opposing arguments

Common Formats of Formal Debates: Within formal debating, there are several distinct formats—each with its own traditions, rules, and objectives.

(a) Parliamentary Debate: Parliamentary debates are modeled after legislative debate systems, particularly the British Parliament and similar democratic institutions.

- Teams: Government (or Proposition) vs. Opposition

- Style: Fast-paced, witty, and spontaneous

- Skills Required: Quick thinking, rebuttal speed, and audience engagement

- Interjections (short, polite interruptions) are allowed to challenge or question the speaker mid-speech, adding energy to the exchange.

For example, a parliamentary debate on climate change policy may see the government team propose specific environmental regulations, while the opposition critiques feasibility, cost, or unintended consequences.

(b) Lincoln–Douglas Debate: Named after the historic 1858 debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, this is typically a one-on-one format.

- Focus: Values, philosophy, and moral principles rather than purely factual policy arguments.

- Structure: Constructive speeches, cross-examination, and rebuttals.

This style encourages deep, thoughtful analysis of ethical issues—for example, debating whether personal privacy should be prioritized over national security.

(c) Policy Debate: Policy debate is the most research-intensive of all formats.

- Teams: Two speakers per side (affirmative and negative).

- Goal: Defend or oppose a detailed policy proposal.

- Content: Evidence-heavy presentations, often involving legal, economic, and technical details.

Speeches are long, and debaters frequently speak at high speed (“spreading”) to fit as much evidence and argumentation into the allotted time as possible.

(d) Public Forum Debate: Public forum debates are designed to be understood by the general public.

- Teams: Two per side.

- Topics: Current events and issues that ordinary citizens can relate to.

- Style: Conversational but still structured; avoids technical jargon.

An example might be debating whether electric vehicles should replace gasoline-powered cars by 2035. The emphasis is on clear communication and persuasion over technical detail.

(e) Mace Debate: This format is closely tied to traditional debating societies, particularly in the UK.

- Teams: Two per side, with a clear motion to be debated.

- Unique Feature: Audience involvement before and after the debate—participants often address questions directly from listeners, and the audience votes on the winning side.

The focus here is both intellectual rigor and public engagement.

(f) Oxford-Style Debate: Oxford-style debates also involve pre- and post-debate audience votes to measure which team has been more persuasive.

- Structure: Opening arguments → Audience Q&A → Closing statements.

- Purpose: To sway public opinion, not just impress judges.

They are common in public intellectual events like those hosted by the Intelligence Squared forum.

(g) Town Hall Debate: Popular in politics and community engagement, Town Hall debates give audience members a direct role in the discussion.

- Questions come from the floor.

- Debaters must adapt to unexpected queries.

This style tests a speaker’s ability to think on their feet and maintain composure when faced with challenging or emotionally charged questions.

(h) Role-Play / Model United Nations (MUN): In Model UN or similar simulations, participants act as diplomats, politicians, or representatives of organizations.

- Goal: Negotiate, form alliances, and create resolutions rather than simply “win” an argument.

- Skills Developed: Persuasion, coalition-building, and cross-cultural communication.

(i) Cross-Examination Debate: While cross-examination is part of many formats, some competitions focus heavily on this skill.

- Purpose: Directly question opponents to reveal weaknesses or contradictions.

- Benefit: Sharpens analytical thinking and quick-response ability.

The variety of debate forms means there is no single “best” way to debate. Informal debates build comfort and openness in communication, while formal debates sharpen precision, discipline, and strategic thinking. Each format—whether the rapid exchanges of Parliamentary style or the ethical depth of Lincoln–Douglas—offers unique opportunities to grow as a communicator, thinker, and engaged citizen.

Sample Debate Starters by Topic:

When stepping into a debate, your opening words set the tone for the entire discussion. They not only convey your position but also grab the audience’s attention and establish credibility. Let’s explore examples of how to begin arguments for different topics—keeping them clear, confident, and compelling.

Topic: “School uniforms should be mandatory.”

Opening (Affirmative): “Good morning, everyone. I stand firmly in favor of the motion that school uniforms should be mandatory. Beyond creating a sense of unity, uniforms bring discipline, reduce peer pressure related to fashion, and foster an environment where students are judged by their abilities rather than their clothes.”

Topic: “Social media does more harm than good.”

Opening (Negative): “Respected judges and audience members, I stand against the motion. Social media, when used wisely, is a tool for connection, a platform for sharing knowledge, and a bridge that links diverse communities worldwide. Its benefits far outweigh the risks when users are educated and responsible.”

Topic: “Should homework be banned?”

Opening (Negative): “I strongly believe homework should not be banned. Homework extends learning beyond the classroom, strengthens concepts taught during lessons, and helps students develop essential life skills such as discipline, time management, and independent problem-solving.”

Top 5 School Debate Topics with Sample Opening Arguments (Affirmative & Negative):

1. Should Homework Be Banned in Schools?

Affirmative Opening: “Good morning, everyone. Imagine a world where students leave school free to pursue hobbies, bond with family, and explore the world around them. I believe homework should be banned because it adds unnecessary stress, limits personal growth, and has little evidence of significantly improving academic achievement.”

Negative Opening: “Respected judges, learning is not limited to the classroom. I oppose banning homework because it reinforces lessons, cultivates self-discipline, and helps students take responsibility for their own learning journey.”

2. Should Social Media Be Restricted for Kids Under 16?

Affirmative Opening: “Ladies and gentlemen, beneath the glossy surface of social media lies a world of unrealistic expectations, distractions, and potential harm to young minds. I support restricting social media for children under 16 to safeguard their mental health and allow them to develop in a healthier, more focused environment.”

Negative Opening: “While concerns about online safety are valid, restrictions are not the answer. I oppose this motion because, when guided responsibly, social media encourages creativity, builds global connections, and equips young people with digital skills they will need for the future.”

3. Should Junk Food Be Banned in School Canteens?

Affirmative Opening: “Our school cafeterias should be places where health and education go hand in hand. I support banning junk food because it promotes healthy eating habits and helps prevent lifestyle diseases like obesity and diabetes from taking root in childhood.”

Negative Opening: “Banning junk food may seem like the easy solution, but it is not practical. Instead of outright bans, we should teach students to make balanced food choices—empowering them to make healthier decisions for life.”

4. Should Students Wear School Uniforms?

Affirmative Opening: “Uniforms are more than just matching clothes—they symbolize equality, discipline, and school pride. I support uniforms because they reduce social barriers, minimize distractions, and encourage students to focus on their studies.”

Negative Opening: “Uniforms may promote equality, but they come at the cost of personal freedom. I oppose this motion because students should be able to express their individuality through their clothing, which is an important aspect of personal growth.”

5. Is Online Learning Better Than Classroom Learning?

Affirmative Opening: “In today’s fast-paced digital world, flexibility and accessibility are essential. I support online learning because it allows for self-paced study, provides access to global resources, and prepares students for the technology-driven workplaces of the future.”

Negative Opening: “Learning is not just about information—it’s about interaction. I oppose the motion because classroom learning fosters social connection, emotional intelligence, and collaborative problem-solving, which no online platform can fully replace.”

Structure of a Debate:

Before you can deliver an effective argument, it’s important to understand the basic structure of a debate. This structure acts like a roadmap, guiding both participants and the audience through a clear, logical flow of ideas. A traditional debate usually follows four main stages:

- Opening Statement: This is where each team introduces its position on the topic. The opening statement sets the tone for the entire debate. It should clearly outline whether the team is arguing for (affirmative) or against (negative) the motion. This is also the moment to capture the audience’s attention, perhaps by using a striking fact, a thought-provoking question, or a short, powerful story. A strong opening not only presents the stance but also gives a preview of the main arguments that will be developed later.

- Constructive Arguments: After the introduction, each team presents its main points, supported by evidence, logic, and examples. This is the “building” phase of the debate—where the foundation of the argument is laid out clearly. Participants often use statistics, expert opinions, historical examples, and real-life situations to strengthen their case. The goal here is to persuade the audience by providing solid, well-structured reasoning that supports the team’s position.

- Rebuttals: In the rebuttal stage, teams directly respond to their opponent’s arguments. This is where listening skills and quick thinking become essential. Debaters point out flaws, inconsistencies, or logical gaps in the other side’s case. A good rebuttal doesn’t just dismiss the opponent’s points—it dismantles them with evidence and reasoning while reinforcing your own position. This back-and-forth exchange is often the most dynamic and engaging part of a debate, as it tests each team’s ability to think critically and adapt on the spot.

- Closing Statements: The final stage is the conclusion, where each team summarizes its key points and delivers a last, persuasive appeal. This is the time to restate the stance with confidence, highlight the strongest arguments, and leave the audience with a clear and memorable impression. A compelling closing often includes a call to action, a powerful quotation, or a thought-provoking statement that stays in the audience’s mind long after the debate ends.

Subsequently, a well-structured debate ensures that every argument is presented in a logical order, giving both the speakers and the listeners a clear understanding of the discussion.

How to Start a Debate Speech:

The opening of your debate speech is one of the most important parts of your performance. It’s your first opportunity to grab the audience’s attention, establish your credibility, and set the tone for the rest of your argument. A strong start can make people eager to listen, while a weak start might cause them to lose interest before you’ve even made your main points. Here’s how to begin effectively:

1. Greet the Audience: Always start by acknowledging and respecting the people you’re speaking to. A polite greeting creates a positive atmosphere and shows professionalism. Your greeting should match the formality of the event. For example:

- “Good morning, respected judges, honorable teachers, and my fellow students.”

- “Good afternoon to the distinguished panel, my opponents, and everyone present here today.”

Keep your tone confident but friendly—this helps you immediately connect with your listeners.

2. Introduce Yourself and Your Position: After your greeting, state your name and clarify whether you are speaking for or against the motion. This is crucial so the audience knows exactly where you stand from the very beginning. For example:

- “I am [Your Name], and I strongly stand in favor of the motion…”

- “I am [Your Name], and today, I will be presenting my arguments against the motion…”

Speaking clearly and confidently here makes a strong first impression and establishes your role in the debate.

3. State the Topic: Next, clearly announce the topic or motion you are debating. This ensures everyone is on the same page and prevents confusion. Keep it formal and precise. For instance:

- “The motion for today’s debate is: ‘Should mobile phones be allowed in schools?’”

- “The topic under discussion today is: ‘Social media does more harm than good.’”

This step is simple but essential—without it, the audience may not follow your argument fully.

4. Provide a Hook or Engaging Opening: To truly capture attention, add a “hook” right after introducing the topic. This could be:

- A surprising fact: “Did you know that over 80% of students use their phones during class time, often for non-educational purposes?”

- A rhetorical question: “What if the very tool we think helps us learn is actually holding us back?”

- A short, vivid story: “Imagine a classroom where every student’s eyes are glued to a glowing screen while the teacher’s words fade into the background…”

The hook works like an invitation—it makes people curious and eager to hear more.

When you combine all these elements—polite greeting, clear introduction, precise topic statement, and a compelling hook—you set yourself up for a confident and engaging debate speech. Remember: first impressions matter, and in a debate, the first 30 seconds can decide whether your audience leans toward you or against you.

Useful Sentence Starters for Debate (Grouped by Function):

In a debate, how you begin your sentences can greatly influence how clearly your arguments are understood. Sentence starters act as signposts for your audience—they guide listeners through your reasoning, highlight important points, and make your delivery smoother and more persuasive. Below are some effective sentence starters, grouped according to their purpose, along with tips on how to use them well.

(A) For Introducing Your Argument: When you’re about to present a new point, you need a clear signal so the audience and judges know you’re shifting to something important. These openers help you structure your arguments logically:

- “Firstly, I would like to point out…” – Ideal for your first point, it sets a formal and confident tone.

- “My first argument is…” – Simple and direct, perfect for beginners.

- “To begin with…” – Works well to ease into your first main idea in a conversational yet formal manner.

Tip: After using these starters, briefly introduce your point before going into details or evidence. This helps keep your speech organized.

(B) For Providing Evidence: Evidence strengthens your credibility and makes your argument more persuasive. These starters help you transition smoothly from an idea to the proof that supports it:

- “According to recent studies…” – Best when you have up-to-date, reliable data. Always mention your source if possible.

- “Research suggests that…” – Works well when presenting general findings from multiple studies.

- “For example…” – Effective for introducing specific cases, stories, or facts that make your argument more relatable.

Tip: Use evidence strategically—too many statistics without explanation can overwhelm the audience, so always connect the evidence back to your argument.

(C) For Contradicting the Opponent: Debates are about presenting your side, but also about responding to and challenging opposing views. These starters help you disagree respectfully while maintaining professionalism:

- “I respectfully disagree with my opponent because…” – Shows politeness while making your counterpoint clear.

- “While my opponent makes a valid point, I believe…” – Acknowledges the other side’s merit before presenting your rebuttal.

- “It is important to note that…” – Works well to introduce information that the opposing side may have overlooked or misinterpreted.

Tip: Always focus on the argument, not the person. This keeps the debate respectful and persuasive.

(D) For Summarizing: The conclusion of your speech should leave a strong final impression. These starters help you wrap up your main points clearly and persuasively:

- “In conclusion…” – A classic closer that signals you’re about to finish.

- “To summarize my main points…” – Useful for reminding the audience of your strongest arguments in a clear order.

- “Therefore, I strongly believe…” – A powerful way to reaffirm your stance and end with confidence.

Tip: Keep your summary concise—highlight your main points and restate your position without introducing new arguments.

When used effectively, these sentence starters can help you deliver a structured, persuasive, and confident debate speech. They guide your audience through your reasoning step-by-step, making it easier for them to follow, understand, and ultimately be convinced by your arguments.

How to Prepare for a Debate:

Preparation is the secret ingredient to a confident and convincing debate performance. For children (and beginners in general), the more time they spend getting ready, the more natural and self-assured they will feel when it’s time to speak. Here’s a step-by-step guide to help them get debate-ready.

1. Understand the Topic: Before writing a single sentence, it’s important to truly understand what the debate is about. Start by carefully reading the topic or motion, and then break it down into smaller parts:

- Identify key terms – What do the important words mean? For example, if the topic is “Homework should be banned,” define “homework” and clarify what “banned” means in this context.

- Set boundaries – Is the discussion about all schools, or just primary schools? Is it about homework in all subjects or only certain ones? Defining these limits prevents confusion later.

- Clarify the purpose – Decide whether the topic is asking for a moral judgment, a practical solution, or both.

Tip: Writing down your own definition of the topic can help you stay focused and avoid drifting off track.

2. Research Both Sides: Even if you know which side you’ll argue for, studying both sides makes you a stronger debater.

- Your side: Gather facts, statistics, examples, and expert opinions to support your arguments.

- Opposite side: Learn the main points your opponents are likely to use. This will help you prepare effective rebuttals and anticipate tricky questions.

- Varied sources: Use books, trusted websites, news articles, and even interviews to collect a balanced set of information.

Tip: Make a list of at least three strong points for each side. This ensures you’re ready no matter what comes up during the debate.

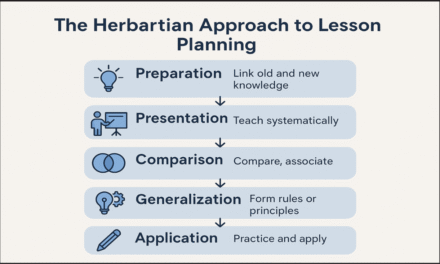

3. Create a Structure: A well-organized speech is easier for both the speaker and the audience to follow. Most debate speeches follow this basic framework:

- Introduction – Greet the audience, introduce yourself, and clearly state your position on the topic.

- Three Main Arguments – Present your strongest points in a logical order, starting with the most important.

- Counterarguments – Address the main points your opponent might raise and explain why they’re flawed or less convincing.

- Conclusion – Summarize your key points and finish with a strong, confident statement that reinforces your stance.

Tip: Keep each section balanced—spending too long on one part can make your speech feel uneven.

4. Practice Delivery: Knowing your speech is one thing—delivering it well is another. Good delivery can make a huge difference in how persuasive you sound.

- Rehearse out loud – This helps you get used to the flow of your words.

- Time yourself – Make sure your speech fits within the given time limit.

- Work on eye contact – Look up from your notes to connect with your audience and show confidence.

- Record yourself – Listen back to check your pace, tone, and clarity.

- Practice with an audience – Present your speech to friends, family, or classmates to get feedback and build confidence.

Tip: If you stumble over certain words or phrases, rephrase them during practice so they’re easier to say under pressure.

With these steps, children will not only be prepared with solid arguments but also feel confident and ready to handle any challenge their opponents throw at them. A well-prepared debater doesn’t just speak—they persuade.

Body Language Tips for Debating:

In a debate, what you say matters—but how you say it can be just as important. Your body language sends powerful signals to the audience and judges, often before you even speak. Confident, open, and engaging body language can make your words more convincing, while nervous or closed-off movements can weaken your message. Here are some practical tips to help you use body language effectively in a debate.

1. Posture – Stand with Confidence: The way you stand tells your audience a lot about your confidence level.

- Stand tall: Keep your back straight, shoulders relaxed but slightly back, and feet shoulder-width apart. This stance makes you look stable and self-assured.

- Avoid slouching: Slumping forward can make you appear nervous or unsure of your points.

- Balance your weight: Don’t sway or rock from side to side—it can be distracting. Instead, plant your feet firmly and only move purposefully when making a point.

Tip: Imagine a string gently pulling you upward from the top of your head. This mental image naturally straightens your posture without making it stiff.

2. Eye Contact – Connect with Your Audience: Eye contact shows confidence and helps your audience feel engaged in your message.

- Look at the audience, not your notes: This makes you seem prepared and sincere.

- Share your attention: Sweep your gaze slowly across the room, making brief eye contact with different people or sections of the audience.

- Avoid staring at the floor or ceiling: This gives the impression that you’re nervous or disconnected from your listeners.

Tip: If direct eye contact feels intimidating, look slightly above people’s heads—it will still appear as if you’re addressing them directly.

3. Gestures – Use Your Hands Purposefully: Your hands can help emphasize your points, but they should look natural—not forced.

- Match your gestures to your words: For example, use your fingers to count when listing points, or spread your hands apart when talking about something broad or important.

- Keep it controlled: Avoid waving your hands wildly or repeating the same gesture too often—it can be distracting.

- Don’t hide your hands: Tucking them into your pockets or crossing your arms can make you seem closed off.

Tip: If you’re not sure what to do with your hands, let them rest naturally at your sides when you’re not gesturing.

4. Facial Expressions – Show Energy and Emotion: Your face is a powerful tool for showing conviction and enthusiasm.

- Smile when appropriate: A friendly smile during your introduction and conclusion helps you appear approachable and confident.

- Match your expression to your words: Show seriousness when making a strong point and excitement when highlighting a key benefit or idea.

- Avoid a blank expression: It can make you seem uninterested, even if your words are strong.

Tip: Practicing in front of a mirror can help you become aware of your expressions and ensure they match your message.

When your posture, eye contact, gestures, and facial expressions all work together, your speech becomes more persuasive and engaging. Remember—your audience doesn’t just hear you, they also see you, and confident body language can make your arguments truly unforgettable.

Voice Tips for Debating:

In a debate, your words carry the content of your argument—but your voice carries its power. A confident, clear, and engaging voice can make your ideas more persuasive, while a rushed, monotone, or too-soft delivery can cause even the best points to lose impact. Here are some practical voice tips to help you make your message heard and remembered.

1. Clarity – Speak So Every Word Counts: Clarity ensures your audience understands exactly what you mean.

- Enunciate clearly: Pronounce each word fully, avoiding mumbling or blending words together.

- Avoid filler sounds: Try to limit “um,” “uh,” or “you know,” as they can distract from your message.

- Slow down tricky words: If a term is complex or new to your audience, pronounce it slowly and clearly so it’s easy to follow.

Tip: Practicing tongue twisters before speaking can warm up your mouth muscles and improve your articulation.

2. Pace – Find a Comfortable Rhythm: Speaking too quickly can make your audience feel rushed; speaking too slowly can make them lose interest.

- Keep a steady pace: Aim for a natural conversational rhythm—not so fast that you stumble, but not so slow that your speech drags.

- Pause with purpose: Brief pauses between points give your audience time to absorb what you’ve said and can create dramatic impact before an important statement.

- Avoid racing through nerves: If you feel nervous, consciously slow down your speech—it will also make you sound more confident.

Tip: Count “one-two” in your head between major ideas to naturally pace your delivery.

3. Volume – Be Heard Without Overpowering: Your volume should match the size of the room and the audience’s needs.

- Speak loudly enough to reach everyone: If the person in the back row is straining to hear you, raise your voice slightly.

- Avoid shouting: Shouting can come across as aggressive; instead, project your voice from your diaphragm for strength and clarity.

- Adjust for emphasis: Increase volume slightly to highlight an important point, and soften your voice when you want the audience to lean in and listen closely.

Tip: Practice speaking while standing at different distances from a friend and ask if they can hear you clearly without strain.

4. Emotion – Let Your Passion Come Through: Your voice can reflect your commitment to your argument.

- Vary your tone: A flat, monotone voice can make even exciting points sound dull. Shift your pitch and inflection to reflect enthusiasm, concern, or determination.

- Match emotion to content: Sound confident when making a strong claim, empathetic when sharing a personal example, and excited when presenting a benefit.

- Avoid overacting: Let your passion sound genuine, not exaggerated.

Tip: Record yourself practicing and listen back to see if your tone matches your words.

When your voice is clear, well-paced, appropriately loud, and filled with genuine emotion, your audience will not only hear your points but feel their importance. The right voice can turn a good argument into a truly memorable one.

How to Handle Counterarguments in a Debate:

A debate isn’t just a platform to share your perspective—it’s also about showing that you can think critically, listen actively, and respond effectively to opposing views. The way you handle counterarguments can make a big difference in how persuasive you appear to the audience or judges. Responding well shows that you have a deep understanding of the topic, can think on your feet, and are confident in your position. Here’s how to handle rebuttals like a skilled debater:

1. Listen Carefully and Stay Focused: When your opponent is speaking, give them your full attention.

- Block out distractions: Avoid planning your reply in your head while they’re still talking—you might miss something important.

- Identify key points: Pay special attention to statistics, examples, or assumptions they use.

- Look for openings: Listen for areas where their argument is weak, contradictory, or missing key evidence.

Tip: Maintain good posture and eye contact while listening. It shows respect and confidence, which can influence how the audience perceives you.

2. Take Useful Notes: If the format allows, jot down quick notes while your opponent speaks.

- Write key phrases, not full sentences: This helps you remember without losing focus.

- Use shorthand for speed: For example, “↑” for increase, “?” for uncertainty, or “!” for an important point.

- Mark priority points: Circle or underline the ones you want to respond to first.

Tip: Use a simple two-column layout—one for your opponent’s points, and one for your planned responses.

3. Respond Calmly, Not Emotionally: Your credibility comes from how composed you remain under pressure.

- Avoid getting defensive: It can make you seem unsure of your position.

- Use measured language: Keep your tone steady and professional, even if the other side is aggressive.

- Focus on logic, not personal attacks: Stick to the argument, not the person making it.

Tip: Take a slow breath before you start your rebuttal—it helps steady your voice and keeps your mind clear.

4. Use Strong, Respectful Rebuttal Phrases: The right phrases can make your counterarguments sound confident and structured:

- Acknowledge before countering: “While that may be true, it does not consider…”

- Directly present your counterpoint: “I would like to counter that by saying…”

- Refer back to solid evidence: “However, the evidence shows…”

Tip: Phrasing your rebuttal with respect prevents you from sounding dismissive and keeps the debate constructive.

Handling counterarguments well is about balance—listen carefully, take notes, stay calm, and respond with evidence and logic. A strong rebuttal not only weakens your opponent’s point but also strengthens your own position in the eyes of the audience.

Debate Practice Activities for Kids:

Practicing debate skills can be fun, creative, and engaging—especially for children. These activities not only help them learn how to form and express their ideas, but also boost their confidence, listening skills, and ability to think on their feet. Here are a few effective ways to make debate practice enjoyable at home or in the classroom:

1. Role Play – Step into Someone Else’s Shoes: Role play is a great way for kids to explore different perspectives.

- How it works: Choose a topic and assign different sides to each child (or small group). One team will argue for the topic, and the other will argue against it.

- Why it works: Children learn to understand and respect multiple viewpoints, even if they don’t personally agree with them.

Extra tip: Encourage them to use props, costumes, or even character voices to make the role play more engaging. For example, if debating “Should school uniforms be mandatory?” one child could play a strict principal while another plays a free-spirited student.

2. Topic Jar – Random Fun with Debate Ideas: The Topic Jar turns debate practice into a surprise game.

- How it works: Write different debate topics on slips of paper and place them in a jar (or box). Kids draw a slip and must prepare to speak on that topic, either for or against it.

- Why it works: It teaches flexibility and quick thinking, since they don’t know what topic they’ll get.

Extra tip: Mix in both serious and silly topics. For example:

- “Should homework be banned?”

- “Is pizza better than ice cream?”

- “Would you rather have a pet dragon or a pet robot?”

3. Two-Minute Challenge – Thinking and Speaking Fast: This activity sharpens the ability to speak clearly under time pressure.

- How it works: Give the child a topic and two minutes to present their opinion. Encourage them to use structured speech—starting with an introduction, giving two or three points, and ending with a short conclusion.

- Why it works: It improves time management, focus, and public speaking skills.

Extra tip: Use debate sentence starters to help them stay organized, such as:

- “Firstly, I would like to point out…”

- “For example…”

- “In conclusion…”

These activities turn debate practice into something playful and exciting, while still building important skills like reasoning, listening, and confident speaking. Over time, kids will not only get better at debating but also enjoy expressing themselves in a thoughtful and persuasive way.

In conclusion, understanding the basics of debate is like learning the rules of a game before you start playing—it gives you the confidence to participate, the tools to make your arguments clear, and the skills to respond thoughtfully to others. Once you know how debates are structured and why they matter, you can focus on expressing your ideas with clarity, listening to different viewpoints with respect, and backing up your stance with solid reasoning. The more you practice, the more you’ll find that debating isn’t just about winning an argument—it’s about learning, growing, and becoming a better communicator in all areas of life.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is the main purpose of a debate?

The primary purpose of a debate is to explore an issue from different perspectives, not just to “win.” It encourages critical thinking, improves communication skills, and helps participants learn to support their opinions with evidence.

Do I need to agree with the side I am assigned?

Not always. In many formal debates, you may be assigned a position—either “for” or “against”—regardless of your personal opinion. This can actually be helpful because it teaches you to think critically and understand viewpoints other than your own.

How is a debate different from a regular discussion?

While a discussion can be casual and unstructured, a debate follows a clear format, has time limits, and involves opposing teams or speakers. Debates also require preparation, evidence, and specific speaking turns, unlike an informal conversation.

What are the most important skills for a good debater?

Strong research skills, clear communication, critical thinking, active listening, and the ability to stay calm under pressure are all essential. Good debaters also use body language and tone effectively to strengthen their arguments.

Can debating help me outside of school?

Absolutely! The skills you gain from debating—such as public speaking, persuasion, teamwork, and analytical thinking—are valuable in everyday life, from job interviews to group projects and even casual conversations.

How long does a debate usually last?

The length of a debate depends on the format. A short classroom debate may last 10–15 minutes, while formal competitions can last an hour or more, with multiple rounds for arguments, rebuttals, and conclusions.

What should I do if I forget my point during a debate?

Don’t panic. Take a brief pause, glance at your notes if you have them, and smoothly continue with your next prepared point. The audience usually won’t notice small slips if you stay confident.

Are emotions allowed in a debate?

Yes, but they should be controlled and purposeful. Showing passion can make your speech more persuasive, but getting overly emotional or aggressive can weaken your credibility.

How important is evidence in a debate?

Evidence is the backbone of a strong argument. Facts, statistics, expert opinions, and real-life examples make your points more convincing and harder for the other side to refute.

Can I use humor in a debate?

If used carefully, humor can help engage the audience and make your speech memorable. However, it should never be offensive or distract from your main argument.

What is the best way to start a debate speech?

Start with a greeting, introduce yourself and your stance, state the topic, and use a strong hook to grab attention.

What are some sentence starters I can use in a debate?

Use phrases like “Firstly, I would like to point out…”, “According to research…”, and “I respectfully disagree…” to build structure and flow.

How can I practice debating at home?

Try mock debates, role-play with family, or use debate topic cards.

What makes a good debater?

A good debater listens well, structures their thoughts, uses strong evidence, and maintains calm body language and voice tone.

References:

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2025). Debate. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/art/debate

- Merriam-Webster, Inc. (n.d.). Debate. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved August 11, 2025, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/debate

- Campbell, J. (2024). Debate. EBSCO. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/education/debate

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Debate. In Wikipedia. Retrieved August 11, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Debate

- Sheffield Hallam University. (n.d.). Debate. Learning and Teaching Academy. Retrieved August 11, 2025, from https://lta.shu.ac.uk/high-quality-teaching/teaching-approaches/debate

- PlanetSpark. (n.d.). How to start a debate. Retrieved August 11, 2025, from https://www.planetspark.in/public-speaking/how-to-start-a-debate

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College