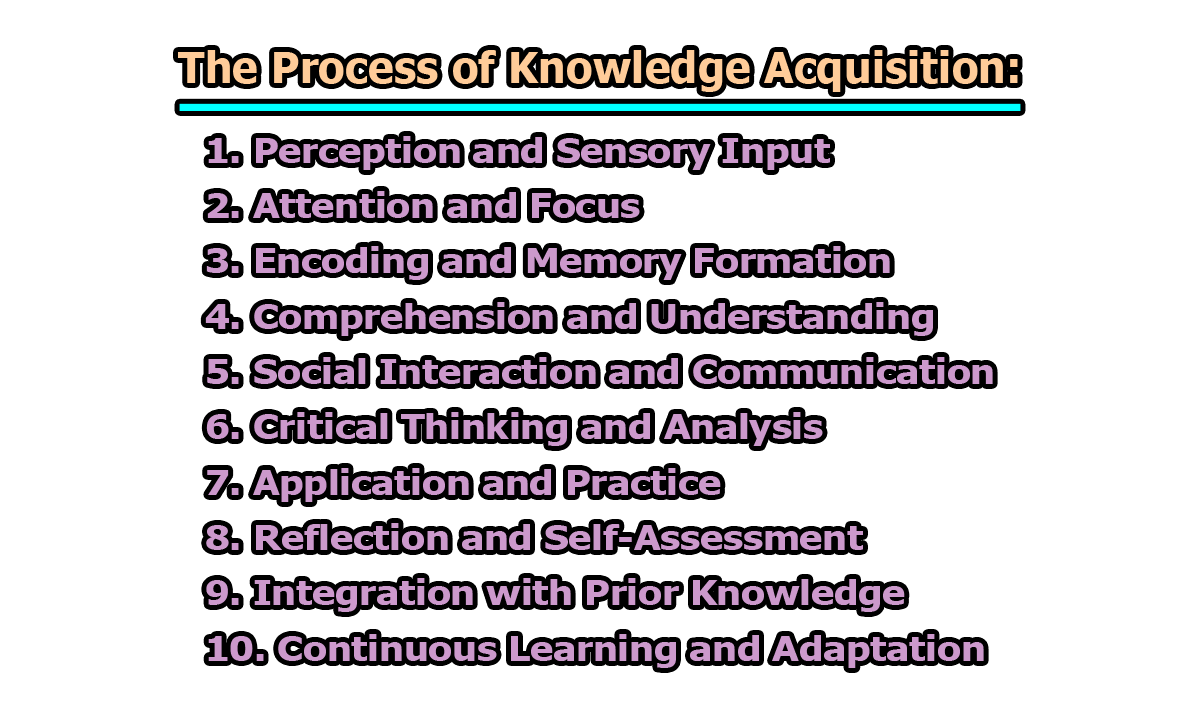

The Process of Knowledge Acquisition:

Knowledge acquisition is the foundation of learning, intellectual growth, and human progress. It is the process through which individuals gather, interpret, and internalize information, turning it into meaningful understanding. This process does not occur instantly; rather, it is a gradual journey influenced by personal experiences, social interactions, education, and critical reflection. By exploring how knowledge is acquired, we gain insight into the mechanisms that shape our thinking, problem-solving abilities, and decision-making. In the rest of this article, we will explore the essential stages or components that outline the process of knowledge acquisition.

1. Perception and Sensory Input: Knowledge begins with perception—the ability to sense and interpret the environment around us. Our five senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch) act as gateways through which raw data enters the brain. Without perception, knowledge cannot even begin to form, because we would have no material to process or interpret.

Example: Imagine a child seeing a dog for the first time. The child observes the dog’s shape, movement, and sound (barking). These sensory impressions become the initial building blocks of knowledge about “what a dog is.” Over time, repeated exposure adds more detail, such as learning that dogs can be friendly or protective.

This stage shows how knowledge starts with raw sensory experience before moving to deeper levels of understanding.

2. Attention and Focus: While the senses constantly receive information, not all of it becomes knowledge. Attention acts as a filter, helping us focus on the most important details while ignoring irrelevant ones. This process is essential because the brain cannot consciously process every piece of information it receives at once.

Example: In a classroom, students may hear background noises like a fan, people whispering, or traffic outside. However, by focusing their attention on the teacher’s voice, they selectively process the relevant information needed for learning. Without this focus, information would pass by without being understood or remembered.

Attention essentially acts as the “spotlight” of the mind, deciding what enters our working memory and eventually transforms into knowledge.

3. Encoding and Memory Formation: For knowledge to last beyond the present moment, it must be encoded into memory. Encoding is the process of taking information and converting it into a form that the brain can store and later retrieve. Different strategies, such as repetition, visualization, and association, strengthen encoding.

Example: A student learning new vocabulary in English may repeat the words aloud, write them in a notebook, and associate them with pictures. By doing this, the brain creates stronger memory connections. Later, when the student sees the word again, it triggers recall because it has already been encoded and stored in long-term memory.

This stage emphasizes that learning is not simply about exposure but about actively working with information so it becomes a part of one’s mental library.

4. Comprehension and Understanding: Comprehension goes beyond remembering facts—it is the stage where learners make sense of information. This means linking new knowledge with existing ideas and recognizing the meaning behind it. Without comprehension, knowledge would remain shallow, much like memorizing words in a foreign language without knowing how to use them in real conversation.

Example: In mathematics, a student may memorize the formula for calculating the area of a triangle (½ × base × height). However, true understanding occurs when the student realizes why the formula works—seeing that a triangle is essentially half of a rectangle. This deeper comprehension allows the learner to apply the formula flexibly to solve different types of problems.

Understanding ensures that knowledge is not just memorized but internalized in a way that can be applied and extended to new situations.

5. Social Interaction and Communication: Knowledge does not grow in isolation. Much of what we learn comes from interacting with others—teachers, peers, parents, colleagues, or even online communities. Conversations, debates, and collaborative projects help us refine our thoughts, challenge assumptions, and expand our perspectives.

Example: A student learning history may gain a certain understanding from textbooks, but when they participate in group discussions, they hear different viewpoints and interpretations. One classmate may highlight the political reasons for a war, while another emphasizes economic causes. This exchange deepens the student’s overall understanding.

This stage highlights how communication acts as a bridge for shared knowledge, making learning a social as well as an individual process.

6. Critical Thinking and Analysis: Not all information we receive is accurate, complete, or trustworthy. Critical thinking helps learners question, evaluate, and analyze the information they encounter. By comparing sources, spotting biases, and testing claims, individuals separate truth from error.

Example: In the digital age, students often encounter conflicting information online. For instance, one website might claim a particular diet cures diseases, while another provides scientific evidence against it. Through critical analysis, the student learns to rely on peer-reviewed studies and credible sources rather than unverified claims.

Critical thinking ensures that knowledge is not just absorbed passively but actively examined, making it more reliable and meaningful.

7. Application and Practice: Knowledge becomes real and lasting when it is put into practice. Applying information in real-world situations allows learners to test its usefulness, identify gaps, and strengthen their understanding. Without practice, knowledge risks fading into forgotten theory.

Example: A medical student can read about surgical techniques in textbooks, but true knowledge develops when they practice procedures under supervision. Similarly, someone learning a new language only becomes fluent by using it in conversations, not by memorizing grammar rules alone.

This stage shows that “doing” is just as important as “knowing.”

8. Reflection and Self-Assessment: Learning is not complete without reflection. Reflection involves thinking critically about what has been learned, how it was learned, and how it can be improved. Self-assessment also helps learners recognize their strengths and weaknesses, which leads to more effective study habits and problem-solving.

Example: After completing a group project, students may reflect on what worked well and what didn’t. They might realize that poor time management limited their success, while collaboration improved their creativity. This reflection helps them perform better in future projects.

Reflection is key to deeper understanding and continuous improvement in knowledge acquisition.

9. Integration with Prior Knowledge: New information is best learned when it connects to something already known. Our brains naturally create networks of related ideas, so integrating new knowledge with prior knowledge makes it more meaningful and easier to recall.

Example: A student learning about photosynthesis in biology will understand it better if they already know about plant structure and sunlight as an energy source. By linking new concepts with old ones, the student builds a strong and interconnected framework of knowledge.

Integration ensures that learning is not isolated but part of a growing system of understanding.

10. Continuous Learning and Adaptation: The process of knowledge acquisition never truly ends. New discoveries, innovations, and changing circumstances constantly reshape what we know. To remain informed and effective, individuals must adopt lifelong learning, updating and adapting their knowledge as needed.

Example: Professionals in fields like technology or medicine cannot rely solely on what they learned in school. A doctor, for instance, must stay updated on new treatments, medical research, and healthcare technologies throughout their career.

Continuous learning ensures that knowledge stays relevant and adaptable in a rapidly changing world.

It is apparent that the process of knowledge acquisition is not a single event but a continuous journey involving multiple interconnected steps. From perception and attention to application, reflection, and lifelong learning, each stage plays a vital role in turning raw information into meaningful understanding. Through social interaction, critical thinking, and practice, knowledge becomes more than facts—it becomes wisdom that guides actions and decisions. By understanding how we acquire knowledge, individuals and societies can foster deeper learning, innovation, and growth.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College