The Importance of Time Management in Research Projects:

Time management is not just about working faster; it is about working smarter. In research, where quality, accuracy, and critical thinking matter, managing time effectively can make the difference between a stressful experience and a successful one. This article explores the importance of time management in research projects, outlines practical strategies researchers can use, and highlights common pitfalls to avoid.

Why Is Time Management So Important in Research Projects?

Time management plays a vital role in determining the success of a research project. Research is not a single task completed in one sitting. Instead, it is a long and demanding process that requires careful planning, sustained effort, and continuous evaluation. Managing time effectively helps researchers remain organized, productive, and mentally focused throughout this journey.

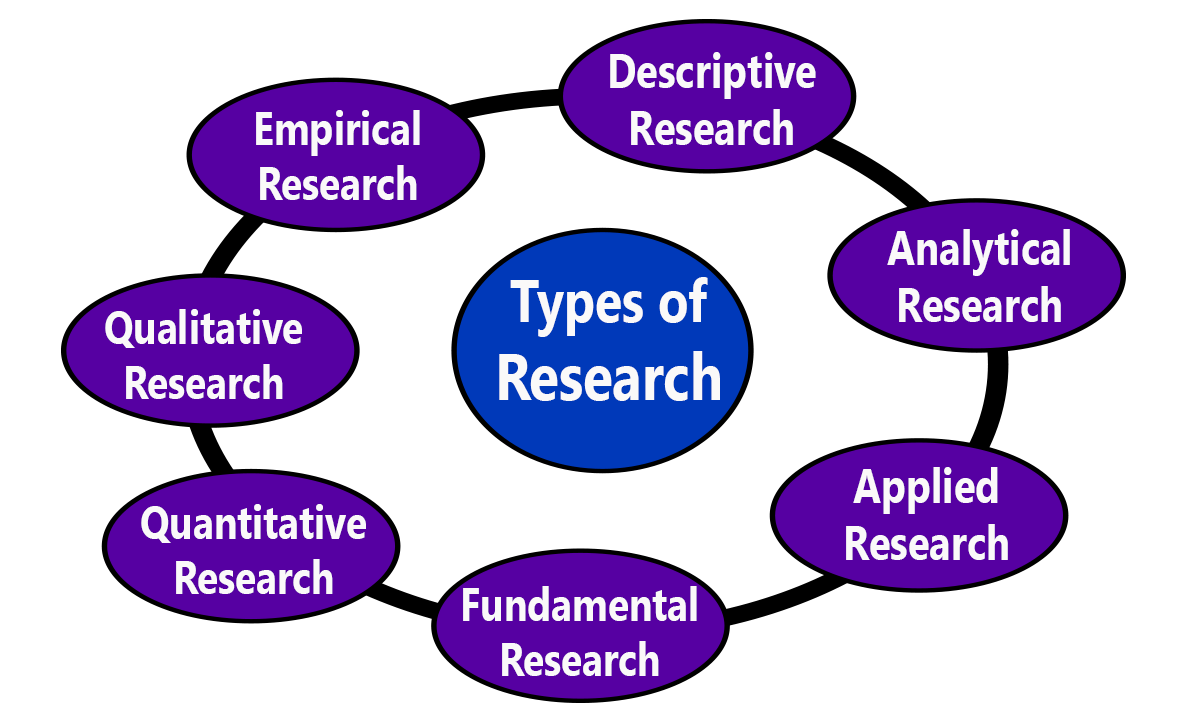

First, research projects are inherently complex and multi-layered. A single project often includes literature review, research design, ethical approval, data collection, data analysis, writing, revision, and sometimes publication or presentation. Each phase requires different skills and levels of concentration. Without effective time management, researchers may spend excessive time on one stage while neglecting others, leading to imbalance and delays. Research shows that structured time planning improves task coordination and reduces inefficiencies in complex academic work (Claessens et al., 2007).

Second, deadlines are unavoidable in research environments. Whether submitting a thesis, meeting funding requirements, or responding to journal reviewers, deadlines are firm and often inflexible. Poor time management increases the likelihood of last-minute work, which is strongly associated with lower performance and higher anxiety. Studies indicate that individuals who plan and monitor their time are more likely to meet deadlines and experience less academic stress (Macan et al., 1990).

Third, effective time management directly influences the quality of research output. High-quality research requires time for reflection, critical analysis, and revision. When researchers rush due to poor planning, mistakes in data analysis, weak argumentation, and overlooked limitations become more common. Empirical evidence suggests that students and researchers who manage their time effectively achieve higher academic performance and produce more coherent and accurate work (Britton & Tesser, 1991).

Fourth, time management supports sustained motivation and focus over long research periods. Research projects often extend over months or years, and motivation naturally fluctuates during this time. Clear schedules and short-term goals help maintain momentum by providing a sense of progress and achievement. Goal-setting research demonstrates that clearly defined, time-bound goals significantly enhance motivation and task persistence (Locke & Latham, 2002).

Fifth, effective time management reduces stress and protects mental well-being. Poorly managed workloads often lead to chronic stress, sleep deprivation, and burnout, especially among graduate students and early-career researchers. Stress not only harms health but also impairs cognitive functioning and decision-making. Studies have shown that individuals who perceive greater control over their time experience lower stress levels and better psychological well-being (Macan et al., 1990).

Sixth, time management improves decision-making and prioritization in research activities. Researchers constantly make decisions about which tasks deserve immediate attention and which can be postponed. Without a clear sense of priorities, time may be wasted on low-impact activities. Effective prioritization allows researchers to focus on tasks that contribute most directly to research objectives, improving overall efficiency and effectiveness (Covey, 1989).

Seventh, managing time well enhances accountability and self-discipline. Research often involves independent work with limited external supervision. In such contexts, time management acts as a self-regulation mechanism, helping researchers stay accountable to their own goals and timelines. Self-regulation studies highlight time management as a key predictor of academic success and task completion in self-directed learning environments (Zimmerman, 2002).

Eighth, time management allows flexibility when unexpected challenges arise. Research rarely goes exactly as planned. Data collection may be delayed, results may be unclear, or new literature may emerge that requires attention. Researchers who plan their time realistically and include buffer periods are better equipped to adapt without panic or major disruption. Flexibility within structured planning is associated with better long-term project outcomes (Claessens et al., 2007).

Finally, effective time management supports a healthier work–life balance. When research tasks are planned and distributed realistically, researchers are less likely to sacrifice sleep, relationships, and personal well-being. Maintaining balance is essential for long-term productivity and creativity, both of which are central to successful research careers (Kabat-Zinn, 2005).

Therefore, time management is not merely a productivity skill but a foundational competence for successful research. It influences quality, motivation, mental health, and the ability to complete projects efficiently and ethically. Researchers who invest time in managing their time ultimately gain greater control over their work and their well-being.

Key Time Management Strategies for Research Projects:

Effective time management in research does not happen by chance. It requires deliberate strategies that help researchers plan, monitor, and adjust their work over time. Because research projects are long, complex, and often self-directed, using structured time management techniques is essential for maintaining progress and quality.

- Break the research project into smaller tasks: Research projects are often large and complex, which can feel overwhelming if viewed as a single task. Dividing the project into smaller activities such as reviewing specific articles, designing instruments, collecting data, or drafting individual sections makes the work more manageable. Research on self-regulated learning shows that breaking tasks into smaller steps improves focus and increases the likelihood of task completion (Zimmerman, 2002).

- Set clear and realistic goals: Clear goals help researchers understand exactly what needs to be done and by when. Goals that are specific and time-bound provide direction and reduce uncertainty. Research on goal-setting theory demonstrates that clearly defined goals lead to higher performance and sustained motivation in complex tasks such as academic research (Locke & Latham, 2002).

- Plan and schedule research activities: Creating a structured schedule allows researchers to allocate dedicated time for reading, writing, analysis, and revision. When tasks are scheduled in advance, researchers are less likely to procrastinate or become distracted. Studies show that planning and scheduling increase perceived control over time, which is linked to better academic performance and lower stress (Macan et al., 1990).

- Use time management tools consistently: Using planners, calendars, or digital task management tools helps researchers track deadlines and monitor progress. These tools reduce mental burden by externalizing planning and organization. Research indicates that individuals who actively plan their time experience greater efficiency and improved task management (Claessens et al., 2007).

- Prioritize tasks based on importance and urgency: Not all research tasks are equally important. Some tasks, such as data collection deadlines or supervisor feedback, require immediate attention, while others can be postponed. Effective prioritization ensures that time is spent on high-impact activities. Time management studies highlight prioritization as a key factor in productivity and stress reduction (Claessens et al., 2007).

- Focus on one task at a time: Although multitasking may appear efficient, research shows that switching between tasks reduces concentration and increases errors. Focusing on a single task allows deeper cognitive processing, which is essential for research activities such as writing and data analysis. Empirical evidence shows that multitasking negatively affects attention and performance (Kuss et al., 2013).

- Schedule regular breaks and rest periods: Continuous work without breaks can lead to mental fatigue and reduced productivity. Short breaks help restore attention and improve overall cognitive performance. Research on mindfulness and well-being suggests that regular rest periods support sustained focus and prevent burnout in demanding intellectual work (Kabat-Zinn, 2005).

- Limit over-commitment and manage responsibilities: Researchers often balance multiple roles, including teaching, administrative tasks, and collaborations. Taking on too many responsibilities can fragment time and slow research progress. Learning to limit commitments helps protect focused research time and maintain productivity. Studies on focused work emphasize the importance of reducing distractions and unnecessary obligations (Newport, 2016).

- Monitor progress and adjust plans regularly: Research projects rarely follow a perfectly linear path. Regularly reviewing progress allows researchers to identify delays and make adjustments before problems become unmanageable. Self-monitoring and reflection are central components of effective self-regulation in academic work (Zimmerman, 2002).

Common Time Management Challenges and How to Avoid Them:

Even with the best of intentions, time management can occasionally go awry. Here are a few common obstacles to be aware of and strategies for avoiding them.

- Procrastination: Procrastination is one of the most common challenges faced by researchers, especially when tasks feel difficult or overwhelming. Delaying work often leads to time pressure and reduced quality of output. Research shows that procrastination is closely linked to anxiety, fear of failure, and task aversion. Breaking tasks into smaller steps and starting with short work sessions can help overcome this tendency (Steel, 2007).

- Poor Planning and Lack of Clear Goals: Without clear planning, researchers may spend time on activities that do not directly contribute to their research objectives. Vague goals make it difficult to track progress and maintain motivation. Studies on goal setting indicate that specific and time-bound goals improve task engagement and performance. Creating weekly and monthly plans can significantly improve research efficiency (Locke & Latham, 2002).

- Underestimating the Time Required for Tasks: Researchers often underestimate how long tasks such as data analysis or writing will take. This leads to unrealistic schedules and missed deadlines. Time estimation errors are common in complex cognitive work. Research suggests that regularly reviewing past task durations and adjusting future plans improves time accuracy and project completion rates (Claessens et al., 2007).

- Perfectionism: Perfectionism can slow progress when researchers spend excessive time refining details that are not yet critical. While high standards are important, excessive perfectionism often results in delayed submission and increased stress. Studies show that adaptive goal regulation and accepting draft-level work before revision help maintain momentum without sacrificing quality (Steel, 2007).

- Distractions and Digital Interruptions: Frequent interruptions from emails, social media, and mobile devices can significantly reduce research productivity. Constant task switching disrupts concentration and increases mental fatigue. Research indicates that minimizing digital distractions and working in focused time blocks improves attention and overall performance (Kuss et al., 2013).

- Multitasking: Many researchers attempt to handle multiple tasks at the same time, believing it saves time. However, cognitive research consistently shows that multitasking reduces efficiency and increases errors, particularly in tasks that require deep thinking such as writing and analysis. Focusing on one task at a time leads to better quality work and faster completion (Kuss et al., 2013).

- Over-commitment to Multiple Responsibilities: Balancing research with teaching, administrative work, and personal commitments can create time pressure. Over-commitment often leads to fragmented schedules and reduced focus. Research on productivity emphasizes the importance of setting boundaries and limiting non-essential commitments to protect dedicated research time (Newport, 2016).

- Lack of Self-Monitoring and Reflection: Some researchers fail to regularly review their progress, which allows small delays to turn into major problems. Self-monitoring helps identify issues early and supports timely adjustments. Studies on self-regulated learning highlight reflection and progress tracking as essential components of effective time management (Zimmerman, 2002).

- Failure to Take Breaks and Rest: Working continuously without rest can lead to cognitive fatigue and burnout. Mental exhaustion reduces creativity, problem-solving ability, and motivation. Research on stress and well-being shows that regular breaks improve sustained attention and reduce emotional exhaustion in demanding academic work (Kabat-Zinn, 2005).

- Resistance to Flexibility and Change: Research projects rarely proceed exactly as planned. Unexpected challenges such as data access issues or methodological changes are common. Rigid schedules can increase frustration when plans change. Time management research suggests that flexible planning with built-in buffer time allows researchers to adapt more effectively without losing overall progress (Claessens et al., 2007).

In conclusion, time management is the backbone of successful research projects. Without it, even the most talented researchers can struggle with missed deadlines, high stress, and compromised work quality. Effective time management enables researchers to navigate complex tasks, meet unavoidable deadlines, maintain high standards, and protect their well-being. By breaking projects into manageable tasks, setting SMART goals, using organizational tools, prioritizing wisely, and avoiding common pitfalls like procrastination and perfectionism, researchers can transform their experience from overwhelming to empowering. Ultimately, managing time effectively is not just about finishing research; it is about doing meaningful, high-quality work while maintaining balance and motivation throughout the journey.

References:

- Baumeister, R. F., & Tierney, J. (2011). Willpower: Rediscovering the greatest human strength. Penguin Press.

- Britton, B. K., & Tesser, A. (1991). Effects of time-management practices on college grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(3), 405–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.83.3.405

- Claessens, B. J. C., van Eerde, W., Rutte, C. G., & Roe, R. A. (2007). A review of the time management literature. Personnel Review, 36(2), 255–276. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480710726136

- Covey, S. R. (1989). The 7 habits of highly effective people. Free Press.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness (15th anniversary ed.). Delta Trade Paperback/Bantam Dell.

- Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Binder, J. F. (2013). Internet addiction in students: Prevalence and risk factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 959–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.024

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

- Macan, T. H., Shahani, C., Dipboye, R. L., & Phillips, A. P. (1990). College students’ time management: Correlations with academic performance and stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(4), 760–768. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.4.760

- Newport, C. (2016). Deep work : rules for focused success in a distracted world (First edition.). Grand Central Publishing.

- Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College