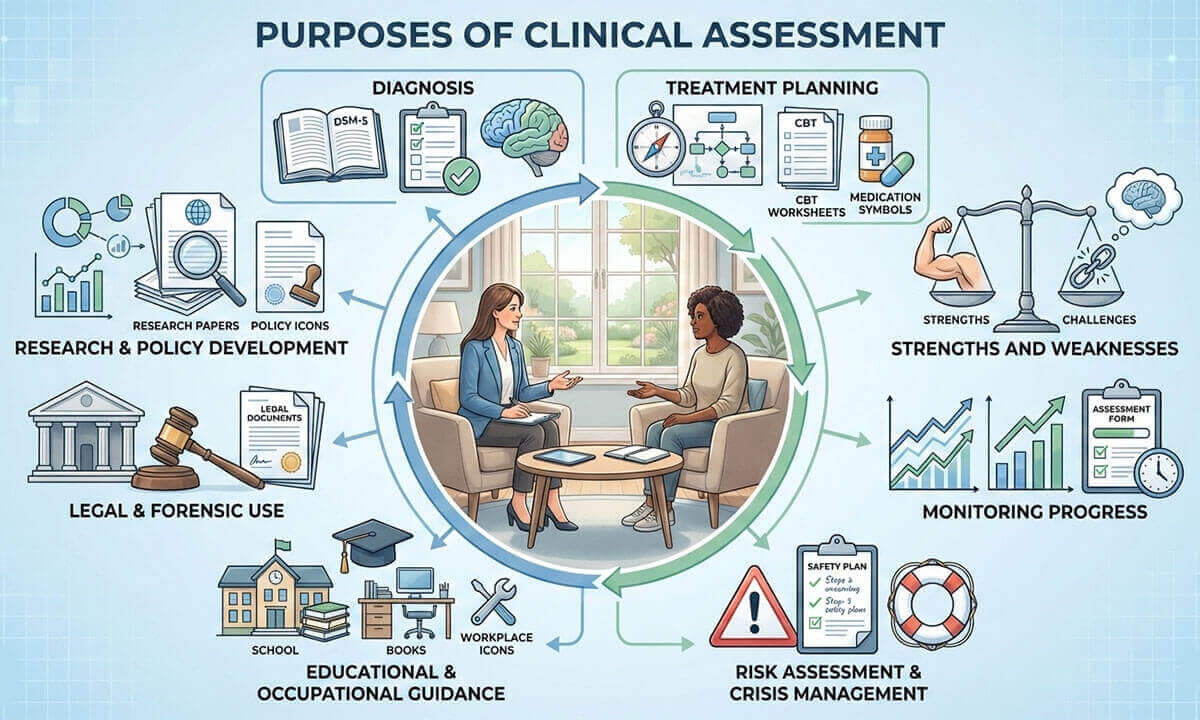

Key Purposes of Clinical Assessment:

Clinical assessment is a cornerstone of professional psychological practice, providing a structured and systematic approach to understanding an individual’s mental health, emotional functioning, and behavioral patterns. Through the careful collection and interpretation of data, clinicians are able to make informed decisions regarding diagnosis, treatment, and intervention. Unlike informal observations, clinical assessment relies on standardized tools, interviews, behavioral observations, and empirical evidence to ensure accuracy and ethical responsibility. As mental health needs continue to increase globally, the purpose of clinical assessment has expanded beyond diagnosis to include treatment planning, progress monitoring, risk management, and contributions to research, education, and legal systems. This article explores the key purposes of clinical assessment.

1. Diagnosis of Mental Health Conditions: One of the most fundamental purposes of clinical assessment is the accurate diagnosis of mental health conditions. Diagnosis involves systematically gathering information about an individual’s symptoms, behaviors, emotional experiences, and level of functioning, and then comparing this information with standardized diagnostic criteria. Clinicians rely primarily on established classification systems such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) to ensure consistency and reliability in diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2022; World Health Organization [WHO], 2019).

Clinical assessment for diagnosis typically includes clinical interviews, behavioral observations, psychological testing, and review of personal, medical, and social history. This comprehensive approach reduces the risk of misdiagnosis, which can occur if conclusions are drawn solely from surface-level symptoms. Accurate diagnosis is essential because it determines the type of treatment provided, eligibility for services, and expectations regarding prognosis (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016).

Example: Consider a client who reports persistent sadness, low energy, and difficulty concentrating. Through clinical assessment, the clinician explores symptom duration, severity, functional impairment, and co-occurring features such as sleep disturbance or feelings of worthlessness. If the symptoms meet DSM-5-TR criteria for Major Depressive Disorder and are not better explained by a medical condition or substance use, an accurate diagnosis can be made. Without a systematic assessment, these symptoms might be incorrectly attributed to stress or personality traits, leading to inappropriate intervention.

2. Treatment Planning: Another crucial purpose of clinical assessment is guiding treatment planning. Once a diagnosis is established, assessment findings help clinicians design individualized treatment plans that address the client’s specific needs, preferences, and contextual factors. Clinical assessment provides detailed information about cognitive patterns, emotional regulation, personality characteristics, interpersonal functioning, and environmental stressors, all of which influence treatment effectiveness (Hunsley & Mash, 2007).

Rather than relying solely on diagnostic labels, clinicians use assessment data to determine which therapeutic approach is most appropriate. For example, assessment may indicate whether cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), psychodynamic therapy, pharmacotherapy, or an integrated approach would be most beneficial. Treatment planning grounded in assessment supports evidence-based practice and enhances therapeutic outcomes (Kazdin, 2021).

Example: A client diagnosed with an anxiety disorder may undergo further assessment revealing pervasive negative thinking patterns and avoidance behaviors. Based on these findings, the clinician may choose CBT, focusing on cognitive restructuring and exposure techniques. In contrast, another client with similar anxiety symptoms but significant interpersonal conflicts and unresolved emotional issues may benefit more from a psychodynamic or interpersonal therapy approach. Clinical assessment ensures that treatment decisions are tailored rather than generic.

3. Evaluating Strengths and Weaknesses: Clinical assessment is not limited to identifying deficits or psychopathology; it also plays an important role in evaluating an individual’s strengths, coping resources, and protective factors. A balanced assessment considers both areas of difficulty and areas of resilience, providing a more holistic understanding of psychological functioning (Snyder & Lopez, 2009).

Identifying strengths (such as effective coping strategies, strong social support, problem-solving skills, or personal motivation) allows clinicians to build upon these assets during intervention. Strength-based assessment contributes to client empowerment, enhances engagement in therapy, and promotes positive outcomes. It also helps counteract the stigma often associated with mental health assessment by emphasizing capabilities alongside challenges (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016).

Example: During the assessment of a client experiencing post-traumatic stress symptoms, the clinician may identify significant strengths, such as strong family support, previous successful coping with adversity, and a willingness to engage in therapy. These strengths can be integrated into the treatment plan by involving supportive family members and reinforcing adaptive coping skills. As a result, the assessment not only identifies trauma-related symptoms but also highlights resources that facilitate recovery.

4. Monitoring Progress and Outcomes: Clinical assessment is an ongoing process that extends beyond initial diagnosis and treatment planning. One of its key purposes is to monitor a client’s progress and evaluate treatment outcomes over time. By administering assessments at different stages of therapy, clinicians can objectively determine whether interventions are effective and whether adjustments are needed (Kazdin, 2021).

Progress monitoring may involve repeated clinical interviews, symptom rating scales, behavioral observations, or standardized psychological tests. These repeated measures help answer important clinical questions, such as whether symptoms have decreased, functioning has improved, or new concerns have emerged. Continuous assessment supports evidence-based practice by ensuring that clinical decisions are guided by data rather than assumptions (Hunsley & Mash, 2007).

Example: A client receiving therapy for depression may complete a standardized depression scale at the start of treatment and at regular intervals thereafter. If assessment results show a significant reduction in symptoms over time, the clinician can conclude that the treatment is effective. However, if scores remain unchanged or worsen, the clinician may modify the treatment plan, introduce additional interventions, or consider alternative approaches. In this way, assessment ensures accountability and responsiveness in clinical care.

5. Risk Assessment and Crisis Management: Another vital purpose of clinical assessment is evaluating risk and managing crises. In certain situations, clinicians must assess immediate threats to the safety of the individual or others. Risk assessment commonly focuses on suicidal ideation, self-harm behaviors, risk of violence, substance misuse, and severe cognitive or psychological impairment (Jobes, 2023).

Risk assessment requires careful clinical judgment, ethical sensitivity, and the use of structured or semi-structured tools when appropriate. The goal is not merely to predict behavior but to understand risk factors, protective factors, and warning signs in order to guide timely and effective intervention. In crisis situations, assessment findings directly inform decisions such as hospitalization, safety planning, or emergency referral (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016).

Example: If a client expresses thoughts of suicide during a therapy session, the clinician conducts a structured risk assessment to evaluate intent, plan, means, and past attempts. If the assessment indicates high risk, immediate actions (such as contacting emergency services, involving family members, or arranging inpatient care) may be necessary. In this context, clinical assessment serves as a crucial tool for ensuring safety and preventing harm.

6. Educational and Occupational Recommendations: Clinical assessment also plays an important role in educational and occupational settings. In educational contexts, assessments are used to identify learning disabilities, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), intellectual disabilities, and developmental delays. The results of these assessments help educators and psychologists design individualized education programs (IEPs), classroom accommodations, and targeted interventions that support academic success (Flanagan & Alfonso, 2018).

In occupational settings, clinical assessment may inform career counseling, vocational rehabilitation, or workplace adjustments. Assessments of cognitive abilities, personality traits, interests, and emotional functioning help individuals make informed career choices and enable employers to create supportive work environments that enhance performance and well-being (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016).

Example: A child who struggles academically may undergo a psycho-educational assessment revealing a specific learning disorder in reading. Based on these findings, the school develops an IEP that includes reading interventions and extended test time. Similarly, in an occupational setting, an adult experiencing job-related stress may receive an assessment indicating burnout and anxiety, leading to recommendations for workload modification, counseling, or career redirection.

7. Legal and Forensic Use: Clinical assessment plays a decisive role in legal and forensic contexts, where psychological findings inform important judicial and administrative decisions. In these settings, assessments are used to evaluate issues such as competency to stand trial, criminal responsibility, risk of reoffending, child custody arrangements, fitness for duty, and civil commitment. Unlike therapeutic assessments, forensic assessments require a high degree of objectivity, methodological rigor, and strict adherence to legal standards (Heilbrun et al., 2014).

Forensic clinical assessments often involve structured interviews, collateral information, psychological testing, and careful documentation. The clinician’s role is not to advocate for the individual but to provide an impartial, evidence-based opinion to assist the legal system. Ethical practice in forensic assessment requires clarity about the purpose of the evaluation, informed consent, and an understanding of the limits of confidentiality (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016).

Example: In a criminal case, a defendant may be referred for a psychological assessment to determine competency to stand trial. The clinician evaluates whether the individual understands the nature of the legal proceedings and can assist in their own defense. If assessment results indicate severe cognitive impairment or active psychosis that interferes with these abilities, the court may decide to delay proceedings and recommend treatment. In such cases, clinical assessment directly influences legal outcomes while maintaining professional neutrality.

8. Research and Policy Development: Clinical assessment also serves an essential function in psychological research and the development of mental health policy. Assessment tools provide systematic and reliable data on psychological functioning, the prevalence of mental disorders, risk factors, and treatment outcomes. These data form the empirical foundation for advancing psychological theory, evaluating interventions, and improving clinical practice (Kazdin, 2021).

At a broader level, assessment findings inform public health initiatives, prevention programs, and policy decisions. Large-scale assessment data help policymakers identify mental health trends, allocate resources, and design services that address population needs. Without standardized and validated assessment methods, research findings would lack consistency and generalizability (Hunsley & Mash, 2007).

Example: Data collected from standardized depression and anxiety assessments across hospitals and community clinics can reveal patterns in mental health prevalence and treatment effectiveness. Policymakers may use this information to expand access to mental health services, develop national prevention strategies, or fund early intervention programs. In this way, clinical assessment contributes not only to individual care but also to systemic improvements in mental health services.

In conclusion, clinical assessment is a vital and multifaceted component of psychology that serves both scientific and practical purposes. It is systematic, individualized, and evidence-based, utilizing a range of tools and methods to comprehensively evaluate psychological functioning. The purposes of clinical assessment extend far beyond diagnosis, encompassing treatment planning, strength identification, progress monitoring, risk management, educational and occupational guidance, legal decision-making, and contributions to research and policy development. Without clinical assessment, psychological practice would lack the structure, clarity, and accountability necessary for ethical and effective care. As mental health challenges continue to rise globally, the importance of clinical assessment becomes increasingly evident in ensuring accurate diagnoses, appropriate interventions, and meaningful support for individuals across diverse settings.

References:

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Flanagan, D. P., & Alfonso, V. C. (2018). Essentials of specific learning disability identification (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Groth-Marnat, G., & Wright, A. J. (2016). Handbook of psychological assessment (6th ed.). Wiley.

- Heilbrun, K., Marczyk, G., & DeMatteo, D. (2014). Forensic mental health assessment: A casebook (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Hunsley, J., & Mash, E. J. (2007). Evidence-Based Assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 29-51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091419

- Jobes, D. A. (2023). Managing suicidal risk: A collaborative approach (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Kazdin, A. E. (2021). Research Design in Clinical Psychology (5th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108993647

- Lopez, S. J., & Snyder, C. R. (Eds.). (2009). Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College