An Overview of Research Paradigms:

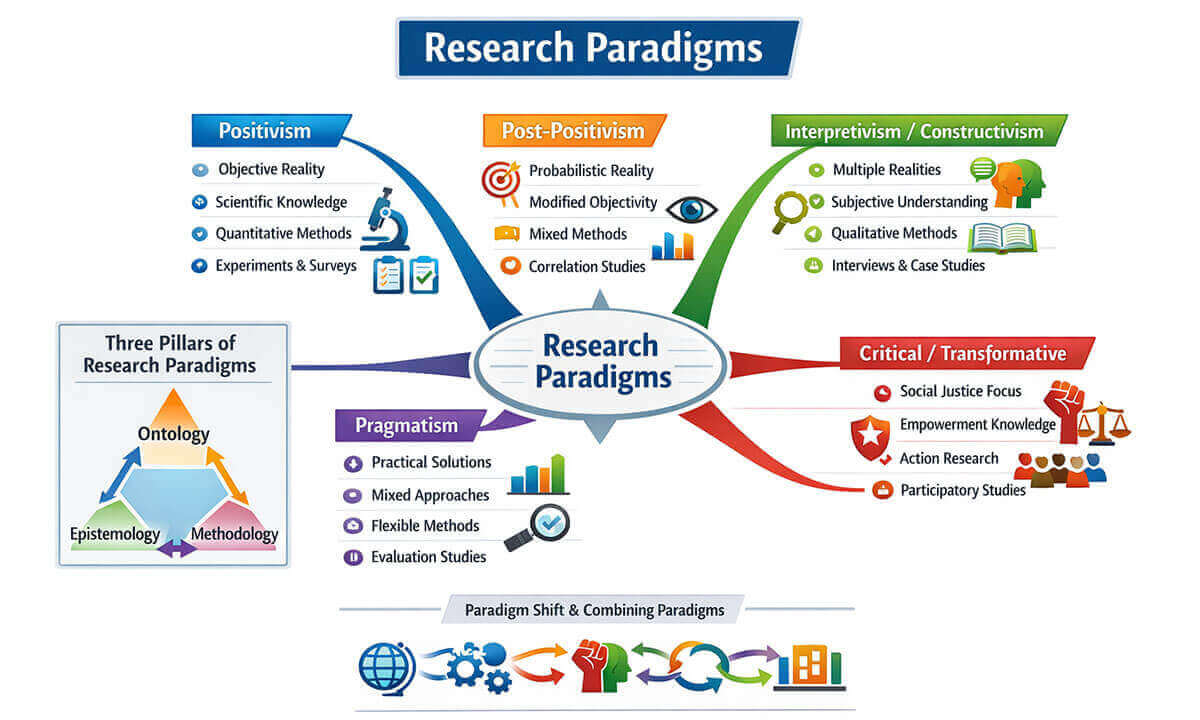

In academic research, scholars do not approach inquiry randomly; instead, their investigations are guided by underlying philosophical assumptions about reality, knowledge, and methods of inquiry. These assumptions collectively form what is known as a research paradigm. Understanding research paradigms is essential because they shape how researchers define problems, choose methodologies, interpret findings, and justify conclusions. Without awareness of paradigms, research risks becoming methodologically inconsistent or philosophically unclear. This article provides an overview of research paradigms by explaining what a research paradigm is, its core pillars, purposes, major types, practical examples, the possibility of combining paradigms, and the steps involved in achieving a paradigm shift.

What Is a Research Paradigm?

A research paradigm refers to a worldview or belief system that guides how research is conducted and understood. It encompasses a set of assumptions about the nature of reality (ontology), the nature of knowledge (epistemology), and the appropriate ways of gaining knowledge (methodology). The concept of paradigms was popularized by Thomas Kuhn in his influential work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, where he described paradigms as shared frameworks that guide scientific practice within a community (Kuhn, 1962).

In social sciences, research paradigms help scholars decide what counts as valid knowledge and which research methods are appropriate for studying a particular phenomenon. According to Guba and Lincoln (1994), paradigms represent “basic belief systems” that influence inquiry at the most fundamental level. Thus, paradigms are not merely theoretical; they directly affect every stage of the research process.

The Three Pillars of Research Paradigms:

Research paradigms are grounded in three interrelated philosophical pillars: ontology, epistemology, and methodology. Together, these pillars shape how researchers understand reality, define knowledge, and choose appropriate strategies for inquiry. A clear understanding of these components is essential for ensuring philosophical coherence and methodological reliability in research.

1. Ontology (The Nature of Reality): Ontology concerns assumptions about the nature of reality and what exists independently of human perception. Ontological positions vary significantly across research paradigms. In positivist and post-positivist paradigms, reality is viewed as objective, singular, and external to the researcher. From this perspective, social phenomena exist independently and can be observed, measured, and explained through empirical investigation (Phillips & Burbules, 2000).

In contrast, interpretivist and constructivist paradigms argue that reality is socially constructed and shaped by human experiences, language, and cultural contexts. Rather than a single objective truth, there are multiple realities, each formed through individual and collective meaning-making processes (Schwandt, 2015). For example, students’ experiences of learning cannot be reduced to a single reality but must be understood within their social and educational contexts.

Critical paradigms adopt a more complex ontological stance, acknowledging that reality is shaped by historical, political, and economic forces. From this view, social structures such as power relations and inequality are real but often hidden, requiring critical examination to be understood and challenged (Habermas, 1971).

2. Epistemology (The Nature of Knowledge and Knowing): Epistemology addresses the relationship between the researcher and what can be known. It focuses on how knowledge is produced, validated, and interpreted. In positivist research, epistemology is grounded in objectivism, where the researcher remains detached and neutral, minimizing bias to uncover universal laws or patterns (Comte, 1853/1975).

Post-positivist epistemology recognizes that complete objectivity is unattainable. Instead, knowledge is viewed as provisional and subject to revision based on evidence and critical scrutiny. Researchers strive for rigor through triangulation, replication, and statistical controls, while acknowledging potential limitations (Phillips & Burbules, 2000).

Interpretivist epistemology emphasizes subjectivity and interaction. Knowledge is co-constructed through dialogue between the researcher and participants, making the research process inherently relational. Meanings are not discovered but interpreted, shaped by context and experience (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). This approach is particularly valuable for exploring beliefs, perceptions, and lived experiences.

Critical epistemology extends this perspective by asserting that knowledge is influenced by power relations and ideological forces. Researchers adopting this stance aim to expose dominance, challenge oppression, and empower marginalized groups through reflective and emancipatory inquiry (Habermas, 1971).

3. Methodology (The Approach to Inquiry): Methodology refers to the overall strategy and design used to generate knowledge, linking philosophical assumptions to practical research methods. It answers the question of how research should be conducted in order to align with ontological and epistemological positions (Crotty, 1998).

Positivist and post-positivist methodologies typically rely on quantitative approaches such as experiments, surveys, and statistical modeling. These methods emphasize measurement, control, and generalizability, enabling researchers to test hypotheses and identify causal relationships (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Interpretivist methodologies favor qualitative approaches, including interviews, observations, ethnography, and case studies. These methods allow researchers to capture rich, contextualized understandings of social phenomena and explore meanings from participants’ perspectives (Schwandt, 2015).

Critical methodologies often incorporate participatory, action-oriented, and transformative approaches. Methods such as critical discourse analysis and participatory action research are used to promote social change while generating knowledge (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

Increasingly, researchers adopt pragmatic methodologies that combine quantitative and qualitative techniques within a single study. This mixed methods approach prioritizes the research problem over strict philosophical allegiance and allows for methodological flexibility (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

Purposes of Research Paradigms:

Research paradigms play a crucial role in shaping the entire research process. They provide the philosophical foundation that guides how researchers conceptualize problems, generate knowledge, and justify methodological decisions. Understanding the purposes of research paradigms enables scholars to conduct coherent, transparent, and intellectually demanding studies.

- Providing Philosophical Orientation and Coherence: One of the primary purposes of research paradigms is to offer a philosophical orientation that ensures coherence throughout a study. Paradigms align researchers’ assumptions about reality (ontology), knowledge (epistemology), and inquiry (methodology), preventing inconsistencies between research questions, methods, and interpretations. Without an explicit paradigm, research risks becoming fragmented or methodologically contradictory (Crotty, 1998).

By clearly situating a study within a paradigm, researchers demonstrate awareness of their underlying assumptions, strengthening the intellectual integrity of the research.

- Guiding the Selection of Research Methods: Research paradigms help researchers determine which methods are most appropriate for investigating a particular phenomenon. For example, positivist paradigms support experimental designs and statistical analysis, while interpretivist paradigms emphasize qualitative approaches such as interviews and observations. This guidance ensures that methods are not chosen arbitrarily but are philosophically justified (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

In mixed methods research, paradigms such as pragmatism allow researchers to integrate multiple methods to address complex research problems effectively (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

- Shaping the Formulation of Research Questions: Another important purpose of research paradigms is influencing how research questions are framed. Positivist paradigms typically focus on cause-and-effect relationships and hypothesis testing, whereas interpretivist paradigms prioritize exploratory questions aimed at understanding meanings and experiences. Critical paradigms frame questions around power, inequality, and social transformation (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

The paradigm thus determines not only what is studied but also how research problems are conceptualized.

- Enhancing Accuracy, Credibility, and Trustworthiness: Research paradigms contribute to the accuracy and credibility of studies by providing criteria for evaluating quality. In quantitative research, validity, reliability, and objectivity are emphasized, while qualitative paradigms prioritize trustworthiness, credibility, and reflexivity. By adhering to paradigm-specific standards, researchers enhance the legitimacy of their findings (Schwandt, 2015).

Explicitly stating the paradigm allows readers and reviewers to assess the study using appropriate evaluative criteria.

- Supporting Interpretation and Meaning-Making: Paradigms play a key role in shaping how data are interpreted and how findings are understood. They influence whether results are viewed as objective facts, subjective meanings, or socially constructed realities. This interpretive function helps researchers draw conclusions that are philosophically consistent and theoretically grounded (Phillips & Burbules, 2000).

- Promoting Transparency and Ethical Awareness: Finally, research paradigms promote transparency by making researchers’ assumptions visible. This openness enables critical reflection and ethical awareness, particularly in studies involving human participants. Critical and interpretivist paradigms, in particular, encourage reflexivity and sensitivity to power dynamics within the research process (Habermas, 1971).

Types of Research Paradigms:

Research paradigms represent distinct philosophical worldviews that guide how knowledge is generated, interpreted, and validated. In social science and educational research, several paradigms are widely recognized, each characterized by unique ontological, epistemological, and methodological assumptions. Understanding these paradigms enables researchers to select approaches that best align with their research questions and objectives.

1. Positivist Paradigm: The positivist paradigm is rooted in the belief that reality is objective, stable, and can be observed and measured through empirical methods. Ontologically, positivism assumes a single reality that exists independently of human perception. Epistemologically, knowledge is considered objective and value-free, with the researcher maintaining detachment from the subject of study (Comte, 1853/1975).

Methodologically, positivist research relies heavily on quantitative approaches such as experiments, surveys, and statistical analysis. Hypotheses are tested using measurable variables, and findings are often generalized to larger populations. This paradigm is commonly used in natural sciences and remains influential in fields such as psychology and education, particularly in experimental research (Phillips & Burbules, 2000).

2. Post-Positivist Paradigm: Post-positivism emerged as a response to the limitations of strict positivism. While it retains the belief in an external reality, it acknowledges that absolute objectivity is unattainable. From a post-positivist perspective, knowledge is provisional and subject to revision as new evidence emerges (Phillips & Burbules, 2000).

Post-positivist researchers emphasize methodological rigor, critical reflection, and the use of multiple measures to reduce bias. Quantitative methods remain central, but qualitative techniques may be used to complement statistical findings. This paradigm is widely adopted in contemporary social science research due to its balanced and pragmatic stance.

3. Interpretivist (Constructivist) Paradigm: The interpretivist, or constructivist, paradigm is based on the assumption that reality is socially constructed through human interaction and experience. Ontologically, it recognizes multiple realities shaped by cultural, historical, and social contexts. Epistemologically, knowledge is co-created by researchers and participants, making subjectivity a central feature of inquiry (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

Methodologically, interpretivist research relies on qualitative approaches such as interviews, focus groups, ethnography, and case studies. The goal is not to generalize findings but to gain deep, contextualized understanding of meanings and lived experiences. This paradigm is particularly valuable in educational and sociological research (Schwandt, 2015).

4. Critical Paradigm: The critical paradigm focuses on examining power relations, social inequality, and systemic injustice. Ontologically, it acknowledges that social realities are shaped by political, economic, and historical forces. Epistemologically, knowledge is viewed as value-laden and influenced by ideology, requiring critical examination (Habermas, 1971).

Methodologically, critical research often employs participatory and emancipatory approaches, such as critical discourse analysis and participatory action research. The aim is not only to understand social phenomena but also to promote transformation and social change. This paradigm is widely used in studies addressing gender, race, education, and social justice (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

5. Pragmatic Paradigm: The pragmatic paradigm prioritizes practical problem-solving over strict adherence to philosophical doctrines. It rejects rigid distinctions between objectivity and subjectivity, focusing instead on what works best to address the research problem. Ontologically and epistemologically, pragmatism is flexible, allowing multiple realities and forms of knowledge to coexist (Morgan, 2007).

Methodologically, pragmatism provides the foundation for mixed methods research, integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches within a single study. This paradigm is particularly useful in applied research contexts, such as education, healthcare, and policy studies (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

Research Paradigm Examples:

In research methodology, positivist and interpretivist paradigms (often aligned with quantitative and qualitative approaches) are commonly regarded as the two foundational research traditions. Positivism emphasizes objectivity, measurement, and causal explanation, whereas interpretivism focuses on understanding meaning and subjective experience. However, contemporary research practice recognizes that these two paradigms do not encompass all ways of knowing. As a result, several additional paradigm variations have emerged to address complex and context-dependent research problems. Some of the most widely used paradigms are discussed below.

- Pragmatism Paradigm: The pragmatism paradigm is grounded in the belief that reality is dynamic and continually shaped by changing social, historical, and practical contexts. Pragmatists reject the notion that inquiry must be confined to a single philosophical tradition. Instead, they argue that research methods should be chosen based on their usefulness in addressing the research problem at hand (Morgan, 2007).

From a pragmatic perspective, both qualitative and quantitative approaches are valuable, and their combination often produces more comprehensive insights. Pragmatists therefore commonly employ mixed methods research, integrating numerical data with contextual and experiential evidence. This paradigm holds that the “best” research method is the one that most effectively answers the research question and informs practical decision-making (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

Pragmatism is particularly influential in applied fields such as education, health sciences, and policy research, where real-world outcomes are prioritized over philosophical purity.

- Constructivist Paradigm: The constructivist paradigm shares foundational assumptions with interpretivism, particularly the belief that reality is not singular or objective but multiple and socially constructed. Constructivists argue that individuals actively construct knowledge through interaction with their environment and through reflection on their experiences (Crotty, 1998).

Constructivist research aims to understand how people make sense of their lived experiences and the meanings they assign to events. Consequently, qualitative methods such as interviews, focus groups, and case studies are commonly used. Rather than seeking universal laws, constructivists focus on answering “why” and “how” questions within specific contexts (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

Beyond research, constructivism is also a prominent theory of learning, particularly in education. It emphasizes experiential learning, problem-solving, and learner engagement, suggesting that individuals learn more effectively through active exploration than through passive instruction (Schwandt, 2015).

- Post-Positivist Paradigm: The post-positivist paradigm emerged in response to critiques of classical positivism. While post-positivists continue to believe in an external reality, they reject the idea that reality can be known with absolute certainty. Instead, knowledge is viewed as probabilistic, tentative, and subject to revision (Phillips & Burbules, 2000).

Post-positivists acknowledge that researchers cannot completely eliminate personal values, assumptions, or biases from the research process. As a result, methodological consistency, critical reflection, and triangulation are emphasized to reduce error and improve the credibility of findings. Quantitative methods remain central, but qualitative approaches may be used to enhance understanding and contextual interpretation (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

This paradigm is widely adopted in contemporary social science research because it balances empirical rigor with philosophical humility.

- Transformative Paradigm: The transformative paradigm challenges the assumptions of both positivism and interpretivism, arguing that these paradigms often fail to capture the lived realities of marginalized and oppressed communities. Transformative researchers assert that research is inherently political and that neutrality may reinforce existing power structures (Mertens, 2007).

Ontologically, the transformative paradigm recognizes that social realities are shaped by systemic inequality, discrimination, and historical injustice. Epistemologically, it values knowledge generated through collaboration with marginalized groups. Methodologically, transformative research frequently employs both qualitative and quantitative methods to examine disparities, promote social justice, and advocate meaningful change (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

This paradigm is commonly used in research focused on gender, disability, race, indigenous knowledge systems, and human rights, where the goal extends beyond understanding to transformation.

Combining Research Paradigms:

In contemporary research, complex social problems often require more than one philosophical lens. As a result, combining research paradigms (particularly through mixed methods research) has become increasingly common. Rather than viewing paradigms as mutually exclusive, researchers focus on complementarity and integration (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010).

The pragmatic paradigm provides the most widely accepted foundation for combining paradigms. Pragmatism allows researchers to draw from both positivist and interpretivist traditions, selecting methods that best address the research question. For example, quantitative data may identify patterns, while qualitative data explain the meanings behind those patterns (Morgan, 2007).

However, combining paradigms requires careful philosophical justification. Researchers must clearly articulate how different ontological and epistemological assumptions are reconciled to avoid conceptual inconsistency. Transparency in paradigm integration enhances the credibility and rigor of mixed methods studies (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

Five Steps to a Paradigm Shift:

Paradigms are not limited to research designs or theoretical frameworks; they also reside within researchers themselves. Every researcher brings a personal worldview shaped by beliefs, experiences, habits, and assumptions, all of which influence how research problems are framed, data are interpreted, and conclusions are drawn. Awareness of one’s personal paradigm is therefore essential for producing high-quality, reflective, and ethically sound research. Kuhn (1962) emphasized that meaningful change in knowledge production often requires a shift in underlying assumptions rather than surface-level adjustments. The following five steps outline how researchers can intentionally shift their personal paradigms to enhance both research quality and personal growth.

1. Identify the Paradigm Element You Want to Change: The first step in a paradigm shift is identifying the specific element of one’s worldview that requires change. This may include deeply held beliefs, habitual ways of thinking, methodological preferences, or unconscious biases that influence research decisions. According to Guba and Lincoln (1994), unexamined assumptions can limit inquiry and constrain interpretation. By critically reflecting on which aspects of their paradigm may be hindering objectivity, creativity, or ethical sensitivity, researchers begin the process of transformation.

This step often involves self-reflection and openness to critique, as paradigm elements are frequently implicit rather than explicit (Schwandt, 2015).

2. Write Down Your Goals: Once the area for change has been identified, researchers should clearly articulate their goals. Writing down specific and achievable outcomes helps clarify intentions and reinforces commitment to change. Goal-setting theory suggests that explicitly stated goals influence motivation and behavior by directing attention and effort toward desired outcomes (Locke & Latham, 2002).

In the context of research, goals may include adopting a new methodological approach, becoming more reflexive, or engaging more ethically with participants. Documenting these goals also encourages accountability and sustained focus throughout the research process.

3. Adjust Your Mindset: A paradigm shift requires intentional changes in mindset. Adjusting one’s mindset involves consciously aligning thoughts, attitudes, and interpretations with the newly defined goals. According to Dweck (2006), individuals with a growth-oriented mindset are more open to learning, feedback, and change; qualities that are essential for paradigm transformation.

Practical strategies for mindset adjustment include reflective journaling, reading foundational methodological texts, engaging with alternative perspectives, and participating in scholarly communities. These activities expose researchers to new ways of thinking and gradually reshape cognitive frameworks (Crotty, 1998).

4. Do Uncomfortable Things: True paradigm shifts rarely occur within comfort zones. Engaging in unfamiliar or challenging activities disrupts habitual patterns and encourages cognitive flexibility. This may involve using unfamiliar research methods, questioning long-held assumptions, or collaborating with scholars from different paradigmatic traditions. Kuhn (1962) noted that intellectual progress often emerges from tension and discomfort rather than stability.

By confronting discomfort, researchers activate deeper levels of reflection and learning, allowing the subconscious mind to move beyond entrenched habits and adopt new perspectives.

5. Practice Being Who You Want to Be: The final step in a paradigm shift is sustained practice. New ways of thinking and behaving must be consistently reinforced until they become internalized as part of a new paradigm. Repetition plays a crucial role in transforming conscious effort into habitual practice (Bandura, 1986).

In research, this means continuously applying new assumptions, methods, and ethical standards across studies. Over time, the old paradigm loses influence, and the new paradigm becomes embedded in the researcher’s identity and scholarly practice. This stage marks the successful consolidation of paradigm change, leading to more reflective, adaptable, and rigorous research.

It is apparent that research paradigms form the philosophical backbone of scholarly inquiry, influencing how researchers understand reality, generate knowledge, and conduct studies. By examining the nature, pillars, purposes, and types of research paradigms, researchers can make informed and coherent methodological choices. In an era of complex research problems, the ability to combine paradigms and adapt to paradigm shifts is increasingly valuable. A clear understanding of research paradigms ultimately enhances the rigor, credibility, and impact of academic research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Why are research paradigms important in academic research?

Research paradigms are important because they provide consistency and clarity in research. They help ensure that research questions, methods, and interpretations align with one another. Understanding paradigms also makes research more transparent and helps readers understand the researcher’s perspective.

How is a research paradigm different from a research method?

A research paradigm is a philosophical framework that guides the overall approach to research, while a research method refers to specific techniques used to collect data, such as surveys, experiments, or interviews. Paradigms influence which methods are chosen, but methods alone do not define a paradigm.

Can a researcher use more than one research paradigm?

Yes, a researcher can use more than one paradigm, especially when addressing complex research problems. This is common in mixed methods research, where qualitative and quantitative approaches are combined to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic.

Which research paradigm is the best?

There is no single best research paradigm. The choice of paradigm depends on the research question, objectives, and context. Different paradigms are suitable for different types of research problems, and the most appropriate one is the one that best addresses the study’s purpose.

How do research paradigms influence data interpretation?

Research paradigms influence how researchers interpret data and explain findings. Some paradigms treat findings as objective facts, while others view them as subjective meanings shaped by context and experience. The paradigm determines how results are understood and presented.

What is a paradigm shift in research?

A paradigm shift refers to a fundamental change in how research problems are understood and studied. It occurs when existing ways of thinking no longer explain new findings, leading researchers to adopt new assumptions, methods, or perspectives.

How can researchers identify their own research paradigm?

Researchers can identify their paradigm by reflecting on their beliefs about reality, knowledge, and the purpose of research. Considering questions about objectivity, subjectivity, and how knowledge should be generated helps clarify one’s paradigmatic position.

Are research paradigms useful outside academic research?

Yes, research paradigms are useful beyond academia. They are relevant in fields such as education, healthcare, social work, and policy-making, where understanding different ways of generating and interpreting knowledge helps improve decision-making and practice.

References:

- Bandura, A., & National Inst of Mental Health. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Comte, A. (1975). The positive philosophy (H. Martineau, Trans.). AMS Press. (Original work published 1853)

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Crotty, M. (1998). The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. London: SAGE Publications Inc.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Sage Publications.

- Habermas, J. (1971). Knowledge and human interests. Beacon Press.

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

- Mertens, D. M. (2007). Transformative paradigm: Mixed methods and social justice. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(3), 212–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689807302811

- Morgan, D. L. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: Methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 48–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806292462

- Phillips, D. C., & Burbules, N. C. (2000). Postpositivism and Educational Research. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Schwandt, T. A. (2015). The Sage dictionary of qualitative inquiry (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2010). Mixed Methodology: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. SAGE Publications.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College