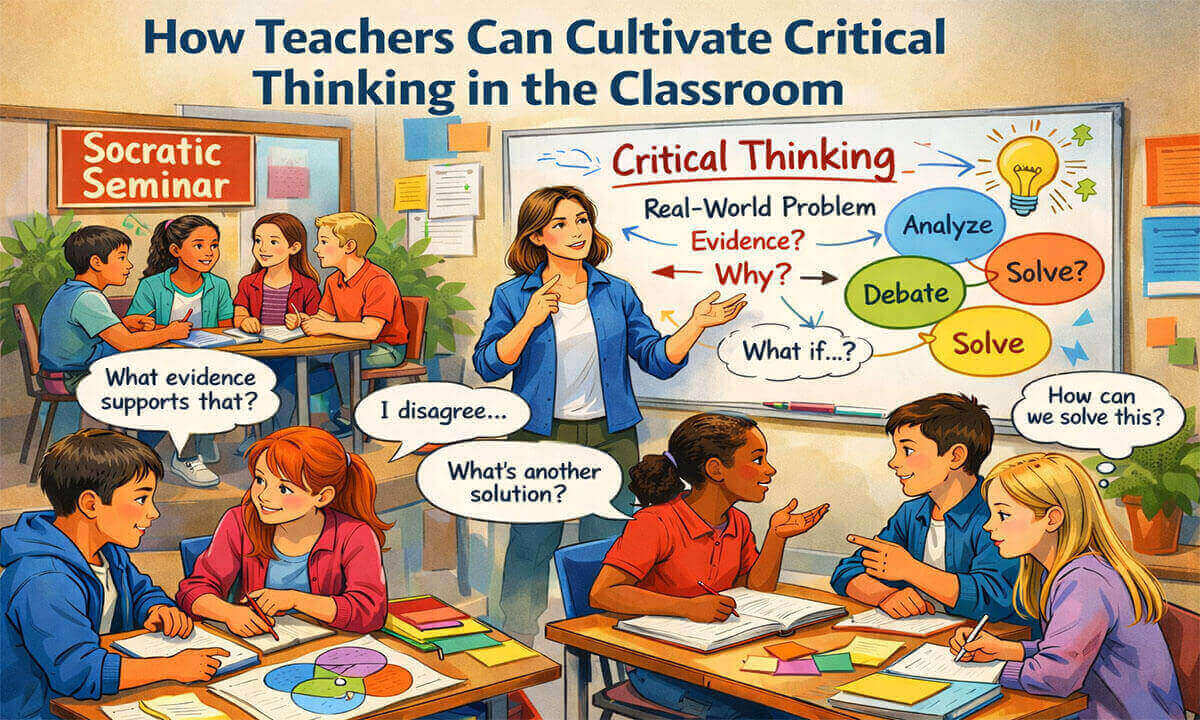

How Teachers Can Cultivate Critical Thinking in the Classroom:

In today’s classrooms, delivering content is no longer the ultimate marker of effective teaching. With information readily available at students’ fingertips, the real challenge lies in teaching learners how to think rather than what to think. Critical thinking (defined as the ability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information to make reasoned judgments) has become a core educational goal across disciplines (Facione, 2015). As students navigate a world saturated with information, misinformation, and competing perspectives, classrooms must evolve into spaces where questioning, reasoning, and reflection are actively cultivated. In the rest of this article, we will explore how teachers can cultivate critical thinking in the classroom.

Why Critical Thinking Matters More Than Ever:

In an era defined by rapid technological change, information overload, and global interconnectedness, critical thinking has become an essential skill rather than an optional academic add-on. Students today are exposed to an unprecedented volume of information through digital media, social networks, and online platforms. While access to information has never been easier, distinguishing credible evidence from misinformation has become increasingly difficult. Critical thinking equips learners with the cognitive tools needed to evaluate sources, identify bias, and make reasoned judgments rather than accepting information at face value (Facione, 2015).

Beyond information literacy, critical thinking plays a central role in preparing students for real-world problem solving. Modern societal challenges (such as climate change, public health crises, and ethical dilemmas surrounding technology) are complex and multifaceted. These issues rarely have single, clear-cut solutions. Research suggests that students who develop strong critical thinking skills are better able to analyze problems from multiple perspectives, weigh evidence, and generate well-reasoned solutions (Halpern, 2014). As a result, critical thinking supports not only academic success but also responsible citizenship and informed decision-making.

Critical thinking is also closely linked to deeper learning and long-term academic achievement. Meta-analytic evidence shows that instructional approaches explicitly designed to foster critical thinking significantly improve students’ higher-order cognitive skills across subject areas (Abrami et al., 2015). When students engage in analysis, evaluation, and reflection, they move beyond rote memorization and develop transferable skills that can be applied in new and unfamiliar contexts. This depth of understanding is particularly important in a knowledge-based economy where adaptability and continuous learning are highly valued.

Furthermore, critical thinking enhances students’ ability to communicate and collaborate effectively. Engaging in reasoned argumentation, defending ideas with evidence, and responding thoughtfully to alternative viewpoints are all core aspects of critical thinking. Classroom practices that emphasize dialogue and academic discussion have been shown to improve students’ reasoning, comprehension, and social understanding (Resnick et al., 2018). These skills are essential not only for academic discourse but also for professional and civic life, where collaboration and clear communication are key.

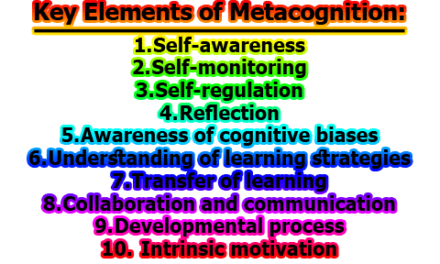

Finally, critical thinking supports metacognition (the ability to reflect on one’s own thinking processes). When students learn to question assumptions, monitor their reasoning, and adjust strategies as needed, they become more autonomous and self-regulated learners (Paul & Elder, 2019). In a rapidly changing world where knowledge quickly becomes outdated, this capacity for self-directed learning is invaluable.

Thus, critical thinking matters more than ever because it empowers students to navigate complexity, engage meaningfully with information, and contribute thoughtfully to society. By prioritizing critical thinking in classroom instruction, educators help students develop the intellectual resilience and adaptability required to thrive in both academic and real-world contexts.

Recognizing the Signs of Shallow Thinking:

Shallow thinking refers to surface-level cognitive engagement in which students focus primarily on memorization and recall rather than understanding, analysis, or evaluation. While the ability to remember information has its place in learning, an overreliance on rote strategies limits students’ capacity to apply knowledge meaningfully. Educational theorists argue that shallow thinking prevents learners from developing the higher-order skills required for critical reasoning and problem solving (Paul & Elder, 2019).

One of the most common indicators of shallow thinking is students’ tendency to repeat textbook definitions or teacher-provided explanations without demonstrating genuine comprehension. In such cases, students may provide answers that are technically correct but are unable to explain why an answer is correct or how it connects to broader concepts. According to Facione (2015), true critical thinking requires interpretation and analysis, not simple reproduction of information. When students struggle to elaborate on their responses or justify their reasoning, it often signals that learning has remained at a superficial level.

Another sign of shallow thinking is the frequent use of minimal or one-word responses, such as “yes,” “no,” or “I don’t know,” particularly when questions are open-ended. These responses suggest limited engagement with the cognitive demands of the task. Research indicates that when classroom questioning emphasizes recall over reasoning, students adapt by offering the shortest acceptable answers, reinforcing surface learning habits (Abrami et al., 2015). Over time, this pattern discourages students from exploring ideas more deeply or taking intellectual risks.

Students who exhibit shallow thinking also tend to avoid open-ended or ambiguous questions. Such questions require analysis, inference, and judgment; processes that can feel uncomfortable for learners accustomed to clear right-or-wrong answers. Halpern (2014) notes that without explicit instruction and practice in higher-order thinking, students may perceive complex questions as threatening rather than intellectually stimulating. This avoidance often results in passive classroom participation and reduced willingness to engage in discussion.

Difficulty transferring knowledge to new situations is another hallmark of shallow thinking. Students may perform well on familiar tasks but struggle when asked to apply concepts to real-world problems or novel contexts. This limitation reflects a lack of conceptual understanding and flexible thinking, both of which are central to critical reasoning (Facione, 2015). When learning remains disconnected from authentic application, students are less likely to see its relevance beyond the classroom.

Recognizing these signs is crucial for educators because shallow thinking is not a fixed trait but a response to instructional conditions. Research emphasizes that when teachers intentionally design learning experiences that promote dialogue, reasoning, and reflection, students are more likely to move from surface-level engagement to deeper, more critical thinking (Resnick et al., 2018). By identifying patterns of shallow thinking early, teachers can adjust their instructional strategies to foster a classroom culture that values understanding over memorization and inquiry over passive acceptance.

Creating a Classroom Environment That Supports Thinking:

A classroom that truly supports critical thinking is built not only on instructional strategies but also on a culture of trust, respect, and intellectual safety. Students are far more likely to engage in deep thinking when they feel comfortable sharing tentative ideas, asking questions, and making mistakes without fear of embarrassment or judgment. Research on classroom discourse emphasizes that psychological safety is a prerequisite for meaningful cognitive engagement, as it encourages students to participate actively in reasoning and dialogue (Resnick et al., 2018).

One essential element of a thinking-supportive environment is the normalization of error as part of the learning process. When mistakes are treated as opportunities for exploration rather than failure, students are more willing to take intellectual risks. Paul and Elder (2019) argue that critical thinking develops through the examination of flawed reasoning and incomplete ideas, making error analysis a powerful learning tool. Teachers who openly discuss misconceptions and invite students to revise their thinking help shift the focus from simply being “right” to understanding why an idea works or does not.

Teacher behavior also plays a central role in shaping the classroom thinking climate. Modeling thinking aloud (by verbalizing how to analyze a problem, question assumptions, or weigh alternative explanations) makes cognitive processes visible to students. Facione (2015) notes that students often struggle with critical thinking because the reasoning behind expert thinking remains hidden. When teachers narrate their thought processes, they provide students with concrete examples of how critical thinkers approach complex tasks.

Another important feature of a supportive thinking environment is dialogic interaction. Classrooms that prioritize discussion, questioning, and collaborative exploration enable students to construct meaning collectively rather than passively receiving information. According to Resnick et al. (2018), academic talk and structured dialogue promote deeper understanding by encouraging students to justify their ideas, listen to alternative perspectives, and refine their reasoning. Such interactions help students internalize the norms of evidence-based thinking and respectful disagreement.

Additionally, a thinking-focused classroom emphasizes metacognitive awareness; helping students reflect on how they learn and think. Encouraging learners to explain their reasoning, evaluate their strategies, and consider alternative approaches fosters self-regulation and intellectual independence (Halpern, 2014). When students are prompted to think about their own thinking, they become more deliberate and purposeful learners.

Consequently, creating a classroom environment that supports thinking requires intentional design and consistent practice. By fostering psychological safety, modeling reasoning, encouraging dialogue, and valuing reflection, teachers lay the foundation for sustained critical thinking. Such environments signal to students that learning is not about passive consumption of information but about active inquiry, thoughtful analysis, and continuous growth.

Asking Better Questions to Promote Deeper Thinking:

Questioning lies at the heart of effective teaching and is one of the most powerful tools for promoting critical thinking in the classroom. The types of questions teachers ask directly shape the depth and quality of students’ thinking. When classroom discourse is dominated by factual or yes–no questions, students are encouraged to recall information rather than analyze, evaluate, or synthesize it. In contrast, thoughtfully designed questions can prompt learners to engage in higher-order thinking and develop more sophisticated reasoning skills (Paul & Elder, 2019).

Open-ended questions are particularly effective in fostering deeper thinking because they require students to explain their reasoning and justify their responses. Questions such as “Why do you think this occurred?”, “What evidence supports your view?”, or “How might this idea change in a different context?” invite students to move beyond surface understanding. Research shows that when teachers consistently use higher-order questions, students demonstrate improved conceptual understanding and stronger critical thinking abilities across subject areas (Abrami et al., 2015).

Effective questioning also encourages students to examine assumptions and consider alternative perspectives. Facione (2015) emphasizes that critical thinking involves interpretation, analysis, and evaluation; processes that are activated when learners are challenged to look at issues from multiple viewpoints. Questions that ask students to compare explanations, predict outcomes, or propose alternative solutions help disrupt passive learning patterns and stimulate deeper cognitive engagement.

In addition, purposeful questioning supports classroom dialogue and collaborative reasoning. When students respond to one another’s ideas rather than solely to the teacher, thinking becomes a shared activity. Research on dialogic teaching highlights that sustained questioning and discussion help students refine their arguments, clarify misunderstandings, and develop more coherent lines of reasoning (Resnick et al., 2018). Teachers can facilitate this process by using follow-up prompts such as “Can you build on that idea?” or “Does anyone see this differently?”

Questioning also plays a vital role in developing students’ metacognitive skills. By asking learners to reflect on how they arrived at an answer or why a particular strategy was effective, teachers encourage students to monitor and regulate their own thinking. Halpern (2014) notes that metacognitive questioning helps students become more intentional learners who can transfer critical thinking skills to new contexts.

Ultimately, asking better questions is not about increasing the number of questions posed but about improving their quality and purpose. When teachers prioritize questions that demand explanation, evidence, and reflection, they create opportunities for deeper learning and intellectual growth. Over time, students internalize these questioning patterns, becoming more curious, analytical, and confident thinkers.

Using Real-World Problems and Authentic Tasks:

Real-world problems and authentic tasks play an essential role in moving students beyond surface-level learning toward deeper, more meaningful thinking. When learning activities are disconnected from students’ lived experiences, knowledge often remains abstract and difficult to transfer. In contrast, authentic tasks situate learning within realistic contexts, requiring students to apply concepts, analyze complex situations, and make informed decisions; core elements of critical thinking (Halpern, 2014).

Authentic tasks typically involve open-ended problems that mirror real-life challenges and do not have a single correct answer. Such tasks compel students to weigh evidence, consider multiple perspectives, and justify their choices. Facione (2015) emphasizes that critical thinking is demonstrated through interpretation and evaluation in contexts that resemble real-world decision-making. For example, asking students to propose solutions to environmental, social, or economic issues encourages them to connect academic content with practical implications.

Research indicates that instructional approaches grounded in real-world problem solving significantly enhance students’ higher-order thinking skills. A meta-analysis by Abrami et al. (2015) found that learning activities requiring analysis, reasoning, and judgment are particularly effective in developing critical thinking when they are embedded within meaningful contexts. These tasks promote deeper engagement because students see the relevance of what they are learning and understand why thoughtful reasoning matters.

Real-world problems also encourage collaboration and dialogue, both of which strengthen critical thinking. When students work together to solve authentic challenges, they must articulate their ideas, listen to alternative viewpoints, and negotiate solutions. Such interactions align with dialogic learning principles, which emphasize reasoning through discussion and shared inquiry (Resnick et al., 2018). Collaborative problem-solving tasks thus help students refine their thinking while developing communication and social reasoning skills.

Furthermore, authentic tasks support the transfer of learning, a key goal of education. Students who engage in applied problem solving are more likely to use their knowledge flexibly in new situations rather than treating learning as isolated facts. Halpern (2014) notes that transfer occurs most effectively when students practice thinking in conditions that resemble real-world contexts. By repeatedly encountering complex, realistic problems, learners develop adaptable thinking strategies that extend beyond the classroom.

In sum, using real-world problems and authentic tasks transforms learning from passive content consumption into active intellectual engagement. By grounding instruction in meaningful contexts, teachers provide students with opportunities to practice analysis, evaluation, and reasoning in ways that reflect real-life demands. Such experiences not only deepen understanding but also prepare students to navigate complex challenges as informed and thoughtful individuals.

Encouraging Debate and Multiple Perspectives:

Encouraging debate and the exploration of multiple perspectives is a powerful way to cultivate critical thinking in the classroom. Debate moves students beyond passive agreement and requires them to actively engage with ideas, evidence, and reasoning. When students are challenged to defend a position or critically examine opposing viewpoints, they practice essential cognitive skills such as analysis, evaluation, and logical reasoning; key components of critical thinking (Facione, 2015).

Structured debates, in particular, provide an effective framework for developing these skills. By researching an issue, organizing arguments, and anticipating counterarguments, students learn to base their claims on evidence rather than opinion alone. Research indicates that instructional approaches emphasizing argumentation significantly enhance students’ reasoning abilities and depth of understanding (Abrami et al., 2015). Through debate, students also develop clarity in communication, as they must articulate ideas coherently and persuasively.

Exposure to multiple perspectives is equally important for developing intellectual flexibility. Paul and Elder (2019) argue that critical thinkers must be able to recognize assumptions, identify bias, and fairly evaluate viewpoints that differ from their own. Classroom debates that require students to consider opposing arguments (or even argue for positions they initially disagree with) encourage empathy and reduce simplistic, black-and-white thinking. This process helps students understand that complex issues often involve competing values and trade-offs rather than clear right-or-wrong answers.

Debate also strengthens classroom dialogue and collaborative reasoning. When students listen actively to peers, respond thoughtfully, and refine their arguments based on feedback, thinking becomes a shared, social process. Research on academic discourse shows that dialogic interaction enhances reasoning quality and supports deeper comprehension (Resnick et al., 2018). Teachers can facilitate productive debate by establishing norms for respectful disagreement and evidence-based discussion.

Moreover, engaging in debate supports metacognitive development by prompting students to reflect on how their thinking evolves. As learners encounter new evidence or compelling counterarguments, they are encouraged to reassess their positions and adjust their reasoning. Halpern (2014) emphasizes that such reflective thinking is essential for transferring critical thinking skills to new contexts beyond the classroom.

In essence, encouraging debate and multiple perspectives transforms the classroom into a space where ideas are examined rather than accepted unquestioningly. By integrating structured debate and perspective-taking activities, teachers help students develop reasoned judgment, intellectual humility, and the ability to navigate complexity—skills that are increasingly vital in academic, professional, and civic life.

Teaching Students to Ask Their Own Questions:

Teaching students to ask their own questions is a fundamental yet often overlooked component of cultivating critical thinking. In many classrooms, students are positioned primarily as respondents rather than inquirers, which can limit their intellectual curiosity and independence. However, the ability to generate meaningful questions is central to critical thinking, as it reflects active engagement, analytical awareness, and a desire to deepen understanding (Paul & Elder, 2019).

When students formulate their own questions, they move beyond passive reception of information and begin to interrogate content more deeply. Question generation requires learners to identify gaps in understanding, recognize assumptions, and evaluate what information is most important. Facione (2015) identifies questioning as a core cognitive skill within critical thinking, emphasizing that thoughtful inquiry drives interpretation, analysis, and evaluation. Students who ask purposeful questions are more likely to engage in deeper reasoning and sustained exploration of ideas.

Instructional strategies that explicitly teach questioning skills have been shown to enhance students’ critical thinking abilities. Research reviewed by Abrami et al. (2015) indicates that students benefit when teachers model different types of questions (such as clarifying, probing, and evaluative questions) and provide structured opportunities to practice generating them. For example, inviting students to create questions before, during, and after a lesson encourages continuous engagement and reflection.

Encouraging student-generated questions also supports metacognitive development. When learners reflect on why they are asking a particular question and how it might guide their learning, they become more aware of their own thinking processes. Halpern (2014) notes that metacognitive awareness strengthens students’ ability to regulate learning and transfer critical thinking skills across contexts. Questioning thus becomes not only a tool for understanding content but also a strategy for self-directed learning.

Furthermore, student questioning enriches classroom dialogue and collective inquiry. When learners share and discuss their questions, classroom discussions become more dynamic and student-centered. Research on dialogic learning highlights that such shared inquiry promotes deeper reasoning and encourages students to build on one another’s ideas (Resnick et al., 2018). Teachers can support this process by valuing student questions as much as correct answers and using them to guide instruction.

Eventually, teaching students to ask their own questions empowers them to take ownership of learning. Rather than viewing knowledge as fixed and unquestionable, students learn to approach ideas with curiosity, skepticism, and openness. By embedding questioning practices into everyday instruction, teachers help students develop habits of inquiry that extend beyond the classroom and support lifelong critical thinking.

Integrating Socratic Seminars and Collaborative Dialogue:

Socratic seminars and collaborative dialogue are powerful instructional approaches for fostering critical thinking by placing students at the center of intellectual inquiry. Rather than relying on teacher-led explanations, these strategies emphasize discussion, questioning, and collective meaning-making. Through structured dialogue, students are encouraged to explore complex ideas, examine evidence, and refine their thinking through interaction with others; key dimensions of critical reasoning (Facione, 2015).

Socratic seminars are typically organized around an open-ended question, text, or problem that does not have a single correct answer. Students engage in thoughtful discussion, drawing on evidence to support their interpretations while responding to alternative viewpoints. This format aligns closely with the principles of critical thinking outlined by Paul and Elder (2019), who stress the importance of questioning assumptions, clarifying meaning, and evaluating the quality of reasoning. By shifting the responsibility for discussion to students, Socratic seminars promote intellectual autonomy and deeper engagement.

Collaborative dialogue within these seminars supports the social nature of thinking. Research on academic discourse demonstrates that reasoning is strengthened when students articulate ideas aloud, listen to others, and revise their thinking in response to new insights (Resnick et al., 2018). Through dialogue, students learn that understanding is not static but evolves through interaction. This process helps them develop skills such as active listening, respectful disagreement, and evidence-based argumentation.

Integrating Socratic seminars also enhances metacognitive awareness. As students reflect on their contributions and evaluate the effectiveness of their arguments, they become more conscious of their own thinking processes. Halpern (2014) highlights that such reflective practice is essential for developing transferable critical thinking skills. Teachers can further support metacognition by incorporating post-seminar reflections in which students assess how their thinking changed during the discussion.

Additionally, Socratic seminars create inclusive opportunities for diverse perspectives. When classroom norms emphasize respect and equal participation, students from different backgrounds and ability levels are more likely to contribute meaningfully. This exposure to varied viewpoints challenges simplistic interpretations and encourages students to consider complexity and nuance; central goals of critical thinking (Facione, 2015).

Subsequently, integrating Socratic seminars and collaborative dialogue transforms classrooms into communities of inquiry. By prioritizing discussion over lecture and reasoning over recall, teachers create spaces where students actively construct understanding together. Such dialogic environments not only deepen content learning but also cultivate habits of thoughtful questioning, reflection, and open-mindedness that extend beyond the classroom.

Assessing Thinking, Not Just Memory:

Assessment plays a decisive role in shaping how students approach learning. When assessments emphasize memorization and recall, students naturally focus on reproducing information rather than understanding it. In contrast, assessments that prioritize reasoning, analysis, and reflection signal that how students think is just as important as what they know. Research consistently shows that assessment practices aligned with higher-order thinking are essential for the development of critical thinking skills (Abrami et al., 2015).

Traditional tests often fail to capture the complexity of students’ cognitive processes. While factual knowledge provides a necessary foundation, critical thinking requires students to interpret information, evaluate evidence, and justify conclusions. Facione (2015) emphasizes that assessment of critical thinking must examine these cognitive skills directly rather than relying solely on correct answers. Performance-based assessments (such as problem-solving tasks, case analyses, and analytical writing) allow students to demonstrate their reasoning in authentic ways.

Reflective assessments are particularly valuable for evaluating students’ thinking. Tools such as learning journals, self-assessments, and reflective essays encourage learners to articulate how their understanding has developed over time. Halpern (2014) notes that reflection strengthens metacognitive awareness by prompting students to examine their strategies, assumptions, and decision-making processes. This focus on reflection helps students become more self-regulated learners who can monitor and improve their own thinking.

Portfolios and longitudinal assessments further support the evaluation of thinking by documenting growth rather than isolated performance. By collecting evidence of learning over time, portfolios reveal patterns in students’ reasoning, problem-solving approaches, and conceptual development. According to Paul and Elder (2019), assessing progress in thinking is essential for helping students recognize strengths and address weaknesses in their reasoning habits. Such assessments emphasize learning as an ongoing process rather than a one-time event.

Assessment practices that involve dialogue and feedback also promote deeper thinking. When teachers provide feedback that focuses on reasoning quality (asking students to clarify explanations or consider alternative perspectives) assessment becomes a learning opportunity rather than merely a judgment. Research on academic discourse highlights that formative feedback and discussion enhance students’ ability to refine and extend their thinking (Resnick et al., 2018).

Ultimately, assessing thinking rather than memory requires a shift in both mindset and practice. By designing assessments that value explanation, evidence, and reflection, teachers encourage students to engage more deeply with content and take ownership of their learning. Such assessment approaches reinforce the message that education is not about recalling information on demand but about developing thoughtful, flexible, and independent thinkers.

Modeling Critical Thinking as a Teacher:

Modeling critical thinking is one of the most effective strategies teachers can use to cultivate this skill in their students. Critical thinking is not solely about content knowledge; it is a process, a set of habits, and a way of approaching problems. Students cannot develop these skills in a vacuum; they need to see them in action. When teachers make their thinking visible, they provide a concrete example of how to question assumptions, weigh evidence, and analyze complex situations (Facione, 2015).

One key aspect of modeling critical thinking is verbalizing thought processes during instruction. Teachers can “think aloud” when solving a problem, analyzing a text, or making a decision, explicitly demonstrating how to approach uncertainty and complexity. For example, a teacher might say, “I’m not sure which solution is best, so let’s examine the evidence for each option” or “I need to consider an alternative perspective before drawing a conclusion”. Such transparency allows students to observe strategies they can later emulate, reinforcing that critical thinking involves exploration, reasoning, and reflection rather than simply arriving at the “right” answer (Paul & Elder, 2019).

Modeling also involves demonstrating intellectual curiosity and openness to new ideas. Teachers who acknowledge the limits of their knowledge (saying, for instance, “I don’t know the answer to this question; what do you think?”) show students that questioning and uncertainty are natural parts of learning. Facione (2015) notes that exposing learners to this mindset fosters resilience and flexibility in thinking, encouraging students to take intellectual risks and engage more fully in inquiry.

Another component of modeling critical thinking is demonstrating metacognitive reflection. Teachers can explain not just what they think but why they are thinking that way, highlighting the reasoning, evidence evaluation, and consideration of alternative perspectives involved. Halpern (2014) emphasizes that such metacognitive modeling helps students develop self-regulation skills, enabling them to monitor and refine their own thinking processes over time.

Finally, modeling critical thinking reinforces classroom culture. When students regularly observe thoughtful analysis, evidence-based reasoning, and reflective discussion, they internalize these behaviors as normative. Resnick et al. (2018) argue that consistent exposure to modeled thinking enhances students’ own cognitive engagement and fosters a collaborative environment where ideas are explored critically rather than accepted passively.

So, teachers serve as the primary role models for thinking behaviors in the classroom. By explicitly demonstrating reasoning, embracing uncertainty, reflecting on thought processes, and showing intellectual curiosity, educators provide students with the tools, strategies, and mindset necessary to become independent, critical thinkers. Modeling is not a one-time event but a continuous, integrated practice that shapes both the skills and the culture of learning.

In conclusion, cultivating critical thinking in the classroom is not about adding one more strategy to an already full curriculum; it is about reshaping how teaching and learning are approached. By creating supportive environments, asking purposeful questions, integrating real-world problems, and assessing reasoning rather than recall, teachers can transform classrooms into spaces of inquiry and intellectual growth. Eventually, educators are not meant to be answer keys but catalysts; sparks that ignite curiosity and sustain lifelong learning. When students leave the classroom still questioning, reflecting, and seeking understanding, critical thinking has truly taken root.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is critical thinking, and why is it important?

Critical thinking is the ability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information to make reasoned decisions. It helps students solve problems, communicate clearly, think creatively, and apply knowledge in real-world situations.

How can I tell if my students are engaging in shallow thinking?

Signs of shallow thinking include:

- Repeating textbook definitions without understanding

- Giving one-word answers like “yes” or “no”

- Avoiding open-ended questions

- Struggling to explain why or how they arrived at an answer

How can teachers create a classroom environment that supports critical thinking?

A supportive environment involves:

- Normalizing mistakes as learning opportunities

- Encouraging open dialogue and collaboration

- Modeling thinking aloud to show reasoning in action

- Promoting reflection on how students think and learn

What types of questions best promote critical thinking?

Open-ended questions are most effective, such as:

- “Why do you think this happened?”

- “What evidence supports your view?”

- “How would you solve this problem differently?”

These questions encourage analysis, explanation, and evaluation rather than memorization.

How do real-world problems and authentic tasks enhance critical thinking?

Real-world problems engage students in meaningful, applied learning. Students weigh evidence, consider multiple perspectives, and justify decisions, which deepens understanding and makes learning more relevant.

What role does debate play in developing critical thinking?

Debate encourages students to analyze issues, consider opposing viewpoints, and defend their reasoning. It builds logical thinking, communication skills, empathy, and the ability to evaluate alternative perspectives.

How can I teach students to ask their own questions?

Encourage students to generate, refine, and prioritize their own questions. Modeling different types of questions and providing structured opportunities for inquiry fosters curiosity and deeper thinking.

What are Socratic seminars, and how do they promote critical thinking?

Socratic seminars are structured, student-led discussions around open-ended questions or texts. They encourage dialogue, evidence-based reasoning, and exploration of multiple perspectives, while teachers guide rather than lecture.

How should I assess critical thinking rather than memorization?

Assessments should focus on reasoning and understanding, such as:

- Performance tasks and projects

- Reflection journals and portfolios

- Rubrics that emphasize thought processes and justification

This approach evaluates how students think, not just what they know.

How can teachers model critical thinking effectively?

Teachers can model critical thinking by:

- Thinking aloud during problem-solving

- Reflecting on assumptions and reasoning

- Showing curiosity and openness to uncertainty

- Demonstrating how to analyze and evaluate ideas

References:

- Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Waddington, D. I., Wade, C. A., & Persson, T. (2015). Strategies for teaching students to think critically: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 85(2), 275–314. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314551063

- Alexander, R. (2020). A Dialogic Teaching Companion (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351040143

- Brookhart, S. M. (2010). How to assess higher-order thinking skills in your classroom. ASCD.

- Chin, C. (2007). Teacher questioning in science classrooms: Approaches that stimulate productive thinking. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(6), 815–843. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20171

- Facione, P. A. (2015). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Insight Assessment.

- Halpern, D. F. (2014). Thought and knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking (5th ed.). Psychology Press.

- Kuhn, D. (2018). A role for reasoning in a dialogic approach to critical thinking. Topoi, 37(1), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-016-9373-4

- Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2019). The miniature guide to critical thinking concepts and tools. Foundation for Critical Thinking.

- Resnick, L. B., Asterhan, C. S. C., & Clarke, S. N. (2018). Socializing intelligence through academic talk and dialogue. AERA.

- Rothstein, D., & Santana, L. (2011). Make just one change: Teach students to ask their own questions. Harvard Education Press.

- Schraw, G., Crippen, K. J., & Hartley, K. (2006). Promoting Self-Regulation in Science Education: Metacognition as Part of a Broader Perspective on Learning. Research in Science Education, 36, 111-139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-005-3917-8

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College