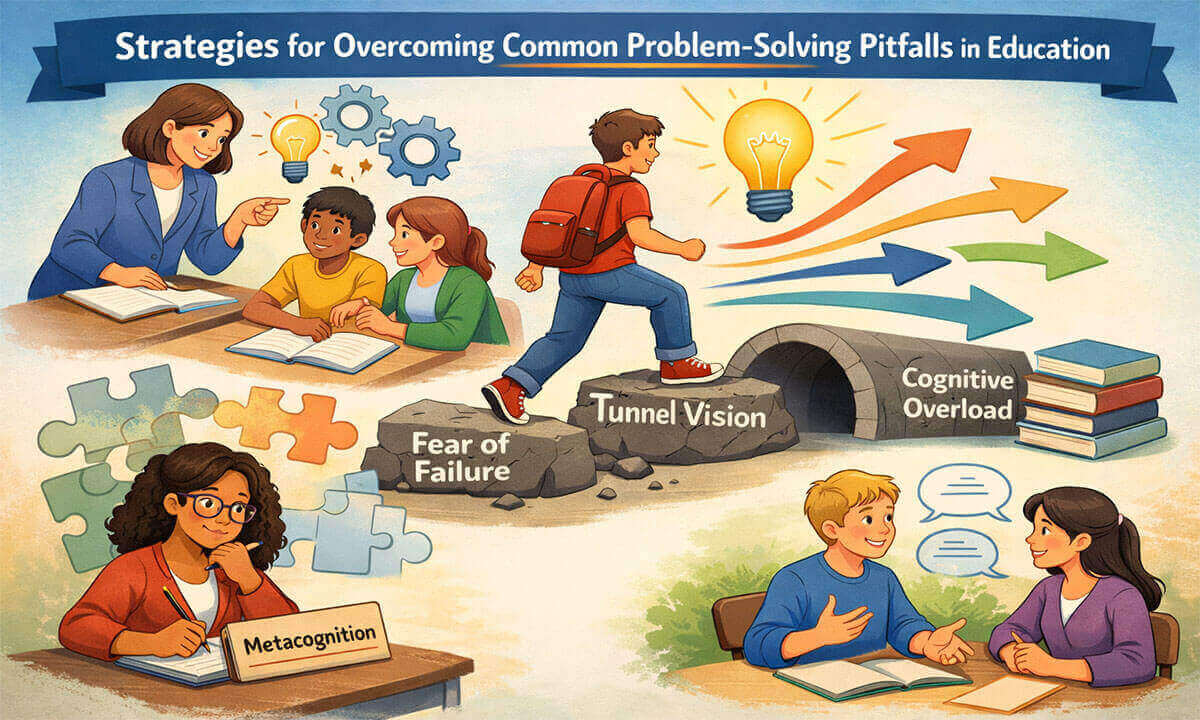

Strategies for Overcoming Common Problem-Solving Pitfalls in Education:

Problem-solving is widely recognized as one of the most essential skills in education, yet it remains one of the most challenging to master. In classrooms, problem-solving is not limited to mathematics or science; it extends to reading comprehension, collaborative projects, decision-making, and even emotional regulation. Despite its importance, learners and educators alike frequently encounter obstacles that hinder effective problem-solving. These obstacles (often referred to as problem-solving pitfalls) can stem from cognitive biases, emotional interference, environmental pressures, or limited strategic awareness. Educational research consistently shows that successful problem-solving is not merely about intelligence or content knowledge, but about how individuals approach problems, regulate their thinking, and adapt strategies when challenges arise. In the rest of this article, we will explore the strategies for overcoming common problem-solving pitfalls in education.

1. Jumping to Conclusions (The Pitfall of Premature Solutions):

One of the most frequent and damaging problem-solving pitfalls in educational settings is the tendency to jump to conclusions. This occurs when students or educators rush toward a solution without fully understanding the nature, scope, or underlying structure of the problem. Under pressure from time constraints, exams, or performance expectations, learners often rely on surface-level cues rather than engaging in deep analysis. Cognitive research shows that novice problem-solvers, unlike experts, are more likely to focus on obvious features of a problem instead of its conceptual foundations (Chi, Glaser, & Rees, 1982).

Jumping to conclusions can result in repeated errors, shallow learning, and frustration. For example, in mathematics, a student may immediately apply a familiar formula without verifying whether the problem conditions actually match that formula’s assumptions. Similarly, in reading comprehension, students may infer meaning based on keywords while overlooking the broader context, leading to incorrect interpretations.

Strategy: Slowing Down and Clearly Defining the Problem: To counteract this pitfall, learners must be encouraged to slow down and deliberately define the problem before attempting a solution. One effective approach is the use of structured questioning techniques such as the “5 Whys,” which help uncover root causes rather than surface symptoms (Serrat, 2017). By repeatedly asking why a problem exists or why an initial attempt failed, students develop analytical depth and avoid impulsive reasoning.

Educational research emphasizes that expert problem-solvers spend a significant portion of their time understanding the problem itself before acting (Jonassen, 2011). When educators model this behavior (by verbalizing how they analyze a problem step-by-step) students learn that careful interpretation is not a delay, but a critical part of successful problem-solving.

2. Tunnel Vision (When Limited Perspectives Block Better Solutions):

Tunnel vision refers to an overly narrow focus on a single solution path, strategy, or assumption while ignoring alternative possibilities. In educational contexts, this often manifests when students believe there is only one “correct” way to solve a problem. This belief can limit creativity, discourage exploration, and reduce adaptability when initial approaches fail.

Cognitive psychology suggests that tunnel vision is closely related to functional fixedness; a mental bias that restricts individuals to familiar uses or methods (Kahneman, 2011). In classrooms that prioritize speed and correctness over reasoning, students may become conditioned to apply the first strategy that comes to mind, even when it is inefficient or incorrect.

Strategy: Encouraging Lateral and Flexible Thinking: Lateral thinking helps learners move beyond rigid patterns and explore alternative solution paths. Encouraging “what if” questions (such as What if I tried this backward? or What if I used a different method?) stimulates creative reasoning and broadens cognitive flexibility. Research shows that exposure to multiple solution strategies enhances both conceptual understanding and transfer of learning across contexts (Rittle-Johnson & Star, 2007).

Teachers play a vital role by modeling multiple ways to approach the same problem and validating diverse reasoning processes. When students see that different methods can lead to equally valid outcomes, they become more willing to explore, revise, and adapt their thinking. This flexibility is a hallmark of expert problem-solvers and an essential skill for real-world learning (OECD, 2017).

3. Fear of Failure (Emotional Barriers to Problem-Solving):

Fear of failure is one of the most powerful emotional obstacles to effective problem-solving in education. In high-stakes academic environments, mistakes are often associated with low ability rather than learning opportunities. As a result, many students avoid challenging tasks altogether, preferring safe but shallow strategies that minimize risk.

Research in educational psychology shows that anxiety and fear significantly impair working memory, which is essential for reasoning and problem-solving (Ashcraft & Krause, 2007). When students are preoccupied with the possibility of failure, cognitive resources are diverted away from the task itself, reducing performance and persistence.

Strategy: Creating a Safe Learning Environment for Mistakes: Addressing fear of failure requires a cultural shift in how errors are perceived. Growth mindset research demonstrates that students who believe abilities can be developed through effort are more resilient and willing to engage with difficult problems (Dweck, 2006). Educators can foster this mindset by framing mistakes as informative feedback rather than evidence of inadequacy.

Simple language choices (such as asking “What did you learn from this attempt?” or “Why do you think this strategy didn’t work?”) can normalize failure as part of the learning process. When classrooms emphasize progress, effort, and reflection, students are more likely to take intellectual risks, persist through difficulty, and ultimately develop stronger problem-solving skills (Hmelo-Silver, 2004).

4. Overcomplicating Solutions: When Simplicity Is Overlooked:

Another common problem-solving pitfall in educational settings is the tendency to overcomplicate solutions. In an effort to appear thorough or avoid mistakes, students may add unnecessary steps, apply multiple formulas, or combine strategies that are not required. While careful thinking is valuable, excessive complexity often increases confusion and cognitive strain rather than improving accuracy.

Cognitive Load Theory explains that working memory has limited capacity, and when learners are overwhelmed with too many steps or pieces of information, their ability to reason effectively decreases (Sweller, Ayres, & Kalyuga, 2011). Overcomplication is particularly evident in subjects such as mathematics, science, and writing, where students may believe that longer or more elaborate solutions are inherently better.

Strategy: Applying the Principle of Simplicity: Encouraging learners to seek the simplest effective solution can significantly improve problem-solving efficiency. The philosophical principle often referred to as Occam’s Razor (that the simplest explanation or solution is usually preferable) aligns well with cognitive research on instructional efficiency. Students should be guided to evaluate their approach by asking whether each step is necessary and whether a more direct method exists.

Teachers can support this strategy by modeling concise problem-solving processes and explicitly demonstrating how unnecessary steps can obscure understanding. When learners are taught to value clarity over complexity, they become more confident and accurate problem-solvers (Jonassen, 2011).

5. Working in Isolation (Limited Perspectives and Missed Insights):

Problem-solving in isolation is another significant pitfall, particularly in academic cultures that emphasize individual achievement over collaborative learning. While independent thinking is important, prolonged isolation can limit perspective and prevent learners from accessing alternative viewpoints that might clarify or simplify a problem.

From a sociocultural perspective, learning is fundamentally a social process. Vygotsky’s theory emphasizes that interaction with others plays a critical role in cognitive development, especially when learners engage in dialogue that challenges and extends their thinking (Vygotsky, 1978). Without such interaction, students may remain stuck in unproductive reasoning loops.

Strategy: Encouraging Collaboration and Open Dialogue: Collaborative problem-solving allows learners to articulate their reasoning, question assumptions, and consider alternative strategies. Research indicates that peer discussion improves conceptual understanding and promotes higher-quality reasoning, particularly in complex problem-solving tasks (Hmelo-Silver, 2004).

Educators can integrate collaboration through structured activities such as think-pair-share, peer feedback sessions, or small-group problem-solving tasks. Even informal discussions (such as explaining a problem aloud to a peer) can trigger new insights. These interactions help learners recognize that problem-solving is not a solitary endeavor but a shared intellectual process (OECD, 2017).

6. Misunderstanding the Problem Context (Solving the Wrong Problem):

A frequent yet often overlooked pitfall in education is misunderstanding what a problem is actually asking. This issue is common in word problems, scientific investigations, and reading comprehension tasks, where instructions may be layered or abstract. When learners misinterpret the context, even strong procedural skills cannot lead to correct solutions.

Research shows that many problem-solving errors stem from poor problem representation rather than lack of knowledge (Chi et al., 1982). If students construct an inaccurate mental model of the problem, their reasoning—no matter how logical—will be misdirected.

Strategy: Rephrasing and Reframing the Problem: Rephrasing the problem in one’s own words is a powerful strategy for improving comprehension and accuracy. This practice aligns with self-explanation research, which demonstrates that learners who actively reinterpret information develop deeper understanding and make fewer errors (Chi et al., 1994).

Teachers can encourage students to restate questions verbally or in writing before attempting solutions. By translating abstract or technical language into familiar terms, learners clarify expectations and reduce misinterpretation. This strategy not only improves immediate performance but also strengthens long-term problem-solving skills by promoting careful analysis and conceptual clarity.

7. Emotional Interference (When Feelings Disrupt Thinking):

Emotional interference is a significant yet often underestimated problem-solving pitfall in educational contexts. Emotions such as anxiety, stress, frustration, and low self-confidence can disrupt attention, reduce working memory capacity, and impair logical reasoning. This issue is especially prevalent in high-pressure academic environments where performance is closely tied to evaluation and grades.

Research in cognitive psychology demonstrates that anxiety consumes cognitive resources needed for problem-solving, leaving fewer mental capacities available for reasoning and decision-making (Ashcraft & Krause, 2007). When learners are emotionally overwhelmed, even familiar tasks can become difficult, leading to avoidance behavior or impulsive errors.

Strategy: Incorporating Emotional Regulation and Mindfulness: To address emotional interference, educators can integrate emotional regulation strategies into everyday instruction. Mindfulness practices, such as brief breathing exercises or reflective pauses, have been shown to reduce stress and improve focus in educational settings (Zenner, Herrnleben-Kurz, & Walach, 2014). These practices help learners become aware of their emotional states and regain cognitive control before engaging in complex tasks.

Additionally, creating an emotionally supportive classroom environment encourages students to express challenges without fear of judgment. When learners understand that emotions influence thinking, they are better equipped to pause, reset, and re-engage with problems productively.

8. Lack of Metacognition (Thinking Without Awareness):

Metacognition (commonly described as “thinking about one’s thinking”) plays a critical role in effective problem-solving. A lack of metacognitive awareness prevents learners from evaluating their strategies, identifying errors, or adjusting their approach when a solution fails. Without reflection, students often repeat the same mistakes, mistakenly attributing failure to lack of ability rather than ineffective strategy use.

Educational research emphasizes that metacognition is a key component of self-regulated learning and academic success (Flavell, 1979). Learners who actively monitor their understanding and performance are more adaptable and efficient problem-solvers.

Strategy: Building Metacognitive Routines into Learning: Explicit instruction in metacognitive strategies significantly enhances problem-solving performance. Techniques such as reflective questioning, learning journals, and post-task debriefs encourage learners to analyze what worked, what did not, and why (Schraw, 1998).

Teachers can embed metacognitive prompts into lessons, asking students to explain their reasoning or evaluate alternative strategies. Over time, these routines help learners internalize reflective habits, enabling them to become more independent and strategic thinkers.

9. Cognitive Overload (Too Much Information, Too Little Processing):

Cognitive overload occurs when learners are presented with more information than their working memory can effectively process. In educational settings, this often happens when complex problems are introduced without sufficient structure, guidance, or prior knowledge. The result is confusion, frustration, and reduced problem-solving efficiency.

Cognitive Load Theory explains that excessive instructional demands hinder learning by overwhelming limited cognitive resources (Sweller et al., 2011). When learners attempt to manage too many elements simultaneously, their ability to reason logically and integrate new information diminishes.

Strategy: Chunking, Scaffolding, and Gradual Complexity: To reduce cognitive overload, educators should break complex tasks into smaller, manageable components; a process known as chunking. Scaffolding strategies, which provide structured support that is gradually removed as competence increases, have been shown to improve problem-solving success and knowledge retention (Kirschner, Sweller, & Clark, 2006).

Visual aids such as diagrams, flowcharts, and worked examples further support comprehension by reducing unnecessary cognitive demands. By managing information load effectively, educators enable learners to focus on understanding each step before progressing, leading to deeper and more durable learning outcomes.

10. Rigid Thinking (Inflexibility in Problem-Solving Approaches):

Rigid thinking is a problem-solving pitfall that occurs when learners cling to a single strategy or method, even when it is clearly ineffective. This inflexibility often develops in educational environments that emphasize procedural accuracy and “one right way” solutions. As a result, students may view abandoning a strategy as failure rather than as a natural and intelligent adjustment.

Research in cognitive psychology suggests that expert problem-solvers differ from novices not in how much they know, but in how flexibly they apply their knowledge (Kahneman, 2011). Rigid thinkers are less likely to explore alternative perspectives, which limits creativity and reduces the likelihood of successful outcomes; particularly in complex or unfamiliar problems.

Strategy: Teaching Strategy Switching and Adaptive Thinking: Overcoming rigid thinking requires explicit instruction in adaptive problem-solving. Strategy switching involves recognizing when an approach is not working and deliberately selecting an alternative method. This ability is a core component of higher-order thinking and problem-solving expertise (Jonassen, 2011).

Educators can promote flexibility by modeling situations in which multiple strategies are attempted before a solution is reached. Encouraging students to ask reflective questions such as “Is there another way to approach this?” or “What strategy could I try next?” helps normalize adaptability rather than perfection. Research indicates that learners exposed to multiple problem-solving strategies demonstrate greater resilience and transfer skills more effectively across contexts (OECD, 2017).

By valuing flexibility and persistence, educators help students understand that effective problem-solving is not about stubbornly sticking to one method, but about responding intelligently to challenges as they arise.

At the end of the day, we can say that problem-solving in education is not merely about arriving at correct answers; it is a dynamic process shaped by cognition, emotion, and environment. Common pitfalls (such as fear of failure, cognitive overload, tunnel vision, and rigid thinking) can derail even capable learners. However, these challenges are not permanent barriers. With intentional strategies grounded in educational research, both educators and learners can navigate around these obstacles effectively. By fostering reflective thinking, emotional safety, collaboration, and flexibility, educational environments can transform problem-solving into a meaningful learning experience. Each pitfall becomes an opportunity for growth, and each challenge a step toward deeper understanding. Ultimately, effective problem-solving is not about avoiding mistakes, but about learning how to think, adapt, and persevere through them.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What are problem-solving pitfalls in education?

Problem-solving pitfalls are common thinking, emotional, or behavioral patterns that interfere with finding effective solutions. In educational settings, these pitfalls may include rushing to conclusions, fear of failure, rigid thinking, emotional stress, or misunderstanding the problem itself. They often prevent students from fully engaging with learning tasks and applying appropriate strategies.

Why do students struggle with problem-solving even when they know the content?

Knowing the content does not always translate into effective problem-solving. Many students struggle due to anxiety, lack of confidence, cognitive overload, or limited metacognitive awareness. These factors can disrupt reasoning and decision-making, even when students understand the subject matter.

How can teachers help students avoid jumping to conclusions?

Teachers can help by encouraging students to slow down, carefully read problems, and identify what is being asked before attempting a solution. Asking guiding questions, modeling step-by-step thinking, and emphasizing understanding over speed can significantly reduce premature conclusions.

What role do emotions play in problem-solving?

Emotions such as stress, fear, and frustration can negatively affect attention and logical reasoning. When students feel overwhelmed or anxious, their ability to process information decreases. Teaching emotional regulation strategies and creating a supportive classroom environment can help students manage these challenges more effectively.

How does collaboration improve problem-solving skills?

Collaboration allows students to share perspectives, clarify misunderstandings, and explore multiple strategies. Discussing problems with peers often leads to deeper understanding and more flexible thinking. Even explaining a problem aloud can help learners identify gaps in their reasoning.

What is metacognition, and why is it important?

Metacognition refers to thinking about one’s own thinking. It helps students monitor their understanding, evaluate strategies, and adjust their approach when necessary. Developing metacognitive skills enables learners to become more independent, reflective, and effective problem-solvers.

How can educators reduce cognitive overload during problem-solving tasks?

Educators can reduce cognitive overload by breaking complex tasks into smaller steps, using visual aids, and providing clear instructions. Gradually increasing task difficulty and offering structured support helps students focus on understanding each part of the problem.

Why is flexibility important in problem-solving?

Flexibility allows learners to adapt when a chosen strategy does not work. Rigid thinking can prevent progress, while flexible thinking encourages experimentation and resilience. Teaching students that changing strategies is a strength, not a weakness, improves problem-solving success.

How can students improve their problem-solving skills on their own?

Students can improve by practicing reflection after solving problems, asking themselves what worked and what didn’t, and seeking feedback from peers or teachers. Managing emotions, staying open to multiple approaches, and practicing regularly also strengthen problem-solving abilities.

How can problem-solving skills benefit learners beyond the classroom?

Problem-solving skills extend beyond academics into everyday life, careers, and decision-making. The ability to analyze situations, adapt strategies, collaborate with others, and persist through challenges prepares learners for real-world problems and lifelong learning.

References:

- Ashcraft, M. H., & Krause, J. A. (2007). Working memory, math performance, and math anxiety. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(2), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194059

- Chi, M. T. H., Glaser, R., & Rees, E. (1982). Expertise in problem solving. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Advances in the psychology of human intelligence (Vol. 1, pp. 7–75). Erlbaum.

- Chi, M.T.H., De Leeuw, N., Chiu, M. and Lavancher, C. (1994) Eliciting Self Explanations Improves Understanding. Cognitive Science, 18, 439-477. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1803_3

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

- Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-Based Learning: What and How Do Students Learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16(3), 235–266. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034022.16470.f3

- Jonassen, D. H. (2011). Learning to solve problems: A handbook for designing problem-solving learning environments. Routledge.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

- OECD (2017). PISA 2015 Results (Volume V): Collaborative Problem Solving. http://www.oecd.org/education/pisa-2015-results-volume-v-9789264285521-en.htm

- Rittle-Johnson, B., & Star, J. R. (2007). Does comparing solution methods facilitate conceptual and procedural knowledge? An experimental study on learning to solve equations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 561–574. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.561

- Schraw, G. (1998). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional Science, 26(1-2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003044231033

- Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Zenner, C., Herrnleben-Kurz, S., & Walach, H. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions in schools-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 603. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00603

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College