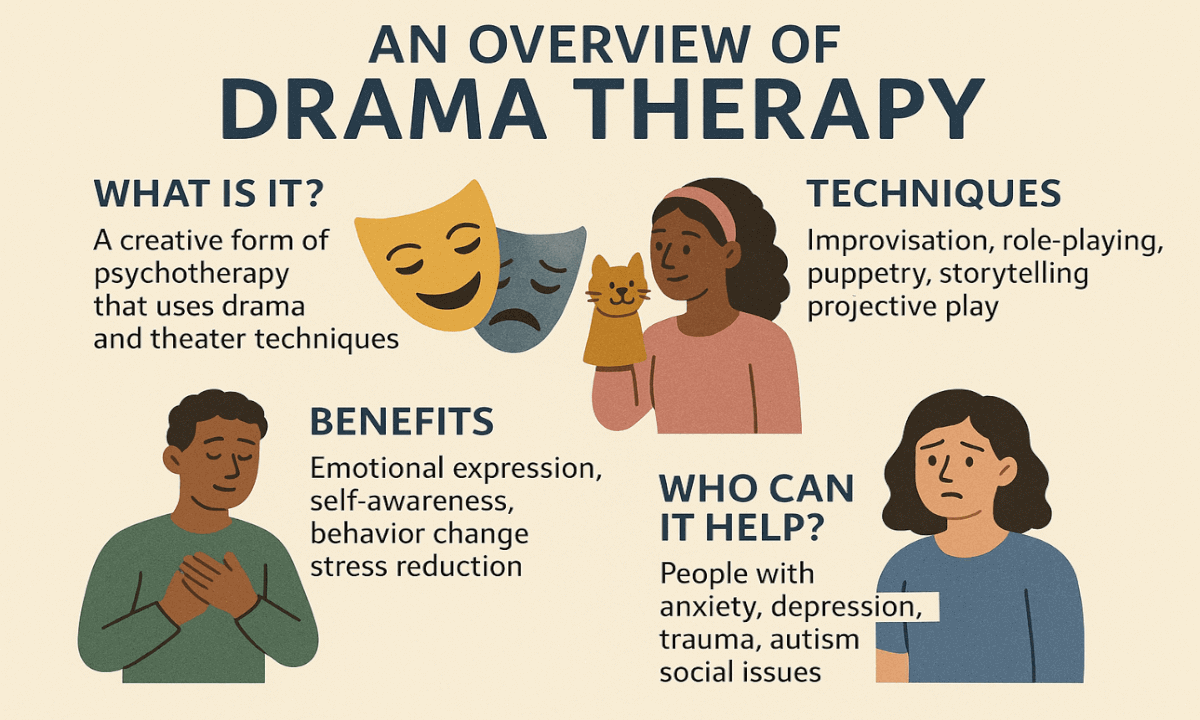

An Overview of Drama Therapy:

Many people who have participated in drama or theater are familiar with the powerful cathartic release it can provide, with actors often shedding tears after a performance and feeling a profound sense of relief. Fortunately, experiencing this kind of release is not limited to joining a theater troupe; it can also be found in drama therapy. Drama therapy is a unique form of therapy that uses “acting out” rather than just “talking it out,” encouraging clients to externalize their inner experiences to support therapeutic processing (Pendzik, 2006). Despite sounding like a modern innovation, drama therapy is a well-established and validated therapeutic approach effective for a wide range of people dealing with diverse problems and disorders (Haen & Weber, 2005; Landy, 1994). In the rest of this article, we will explore an overview of drama therapy.

What Is Drama Therapy?

Drama therapy is a dynamic and integrative form of expressive arts therapy that combines the creative power of theater with psychological processes to promote growth and change. It uses theatrical techniques—such as role play, improvisation, storytelling, script work, and performance—to help individuals explore and express complex feelings, practice new ways of interacting, and rehearse healthier behaviors in a safe and supportive environment.

Unlike traditional talk therapy, drama therapy actively engages the body, mind, and emotions, making it particularly helpful for clients who may struggle to articulate their experiences verbally or feel stuck using conventional methods. By stepping into roles and enacting scenarios, individuals can gain new perspectives on their life stories, resolve inner conflicts, and experiment with different solutions to real-life challenges (Pendzik, 2006).

The North American Drama Therapy Association (NADTA; n.d.a, para. 2), the leading professional organization in this field, defines drama therapy as an approach that “can provide the content for participants to tell their stories, set goals and solve problems, express feelings, or achieve catharsis.” This definition highlights the diverse applications of drama therapy—whether it’s helping someone process grief through role play, empowering survivors of trauma to reclaim their narratives, or providing a creative outlet for emotional release.

Research supports its effectiveness across a variety of populations, including children, adolescents, adults, and older adults, and for issues ranging from anxiety and depression to social skills development and trauma recovery (Haen & Weber, 2005; Landy, 1994).

From the writer’s perspective, what makes drama therapy particularly compelling is its ability to tap into the deep human need for storytelling and performance—a need that has existed for centuries across cultures. It reminds us that healing doesn’t always have to come from talking alone; sometimes, it comes from stepping into a new role, embodying our struggles and hopes, and finding freedom and insight through creative expression.

The Early Roots of Drama Therapy:

The concept of using drama as a therapeutic tool is not a recent innovation but has roots reaching back over a century. One of the earliest known texts on the subject, published in 1917, proposed that drama therapy works by giving individuals an opportunity to externalize their internal struggles. By bringing these inner challenges to life through dramatic enactment, people can engage with them safely and experiment with different aspects of their personality through playful exploration (Austin, 1917). This early insight laid a crucial foundation for understanding how theater could serve as a bridge between imagination and psychological healing.

Around the same time, Jacob Moreno, a pioneering psychiatrist and theater director, began developing psychodrama—a method that significantly influenced modern drama therapy (Langley, 2006). Unlike the dominant psychoanalytic models of the time, which focused heavily on analyzing the past (as popularized by Freud and his followers), psychodrama emphasized action in the present and the exploration of possible futures. In psychodrama sessions, participants would enact real-life scenarios, take on different roles, and reimagine outcomes, helping them gain insight, process emotions, and develop new coping strategies. Moreno’s work highlighted the transformative potential of dramatic enactment in therapy, setting the stage for the broader field of drama therapy to emerge.

Building on these early explorations, drama therapy gradually developed as a distinct therapeutic practice that draws from both theater arts and psychological principles. To bring cohesion and professional standards to this growing field, the North American Drama Therapy Association (NADTA) was founded in 1979 (North American Drama Therapy Association, n.d.a). The NADTA continues to play a vital role today, providing ethical guidelines, training standards, and a professional community for drama therapists across North America and beyond.

Through these historical milestones—from Austin’s early ideas to Moreno’s psychodrama and the formal establishment of the NADTA—drama therapy has evolved into a respected and evidence-based modality that continues to help countless individuals transform their inner worlds through the creative power of performance and play.

Drama Therapy vs. Psychodrama Therapy:

People often wonder about the difference between drama therapy and psychodrama therapy—a confusion that is understandable but technically misplaced. The question itself stems from a common misconception: psychodrama is not separate from drama therapy; rather, it is one specialized method within the broader field of drama therapy (Giacomucci & Marquit, 2020).

Psychodrama is a specific technique that focuses on using guided role-play, dramatic reenactment, and spontaneous improvisation to help individuals gain deeper insight into themselves and their relationships (Giacomucci & Marquit, 2020; Orkibi & Fenger-Schaal, 2019). In a typical psychodrama session, a client might recreate scenes from their life, enact unresolved conflicts, or rehearse future interactions. By embodying roles and exploring these moments in action, the individual can confront difficult emotions, test new behaviors, and work through complex interpersonal dynamics in a safe, supportive environment.

However, psychodrama is just one method in the diverse toolkit of drama therapy. While psychodrama typically focuses on individual clients or small groups working through specific personal or relational issues, drama therapy encompasses a much wider range of practices. These might include ensemble-based performances, therapeutic storytelling, scripted plays, improvisation games, mask work, puppetry, and other creative interventions that serve different therapeutic goals and populations.

In other words, all psychodrama is drama therapy, but not all drama therapy is psychodrama. Drama therapy’s strength lies in its flexibility and breadth—it draws from many theatrical traditions to design interventions that best fit the unique needs, cultures, and contexts of the participants.

Understanding this distinction helps clarify that psychodrama is a foundational pillar within drama therapy, but the larger field includes many other creative and therapeutic applications that extend far beyond this single technique (Giacomucci & Marquit, 2020; Orkibi & Fenger-Schaal, 2019).

What Does a Drama Therapy Session Look Like?

Modern drama therapy sessions are thoughtfully structured to guide participants through a safe and creative therapeutic process. Although they can vary based on the therapist’s approach, the client’s needs, and the setting, they typically follow four key stages (Nicholls, 2024).

- The Check-In: A session usually begins with a check-in, where the therapist invites participants to share how they are feeling that day. This part is crucial because it sets the emotional tone and helps the therapist gauge each person’s mental and emotional state before diving into deeper work. The check-in can be as simple as a short conversation, or it might include creative prompts, like expressing current feelings through gestures or simple movement.

- The Warm-Up: Following the check-in, the therapist leads a warm-up. This phase helps participants loosen up, shake off inhibitions, and prepare their minds and bodies for creative engagement. Warm-ups might include physical exercises, vocal games, improvisation games, or simple group activities designed to build trust and focus. The goal is to create a sense of playfulness and safety, allowing participants to step more comfortably into dramatic roles or scenarios later in the session.

- The Main Activity: The main activity is the heart of the session and where the core therapeutic work takes place. Here, the therapist guides individuals or the group through structured dramatic exercises. This could involve role-play, improvisation, storytelling, script work, mask work, or other dramatic forms tailored to the group’s goals. During this stage, participants might explore personal stories, enact conflicts, experiment with new perspectives, or rehearse healthier behaviors. The main activity allows for deep emotional expression, insight, and the opportunity to practice change in a creative, embodied way.

- Closing: Finally, the session concludes with closing. In this phase, the therapist facilitates a reflective discussion, inviting participants to share their thoughts, feelings, or discoveries from the main activity. The closing helps people process what emerged during the session and connects the dramatic work back to real-life situations and goals. The therapist may highlight lessons learned, reinforce key insights, and ensure everyone leaves feeling grounded and supported.

While drama therapy sessions often resemble aspects of traditional talk therapy, they stand out through their use of dramatization, active emotional expression, imagination, and creative play. This unique structure makes drama therapy a powerful option for individuals and groups seeking an alternative to traditional, solely verbal forms of therapy.

The Psychology Behind Drama Therapy:

At first glance, drama therapy might sound like one of the latest fads to catch the attention of therapists and clients searching for creative healing methods. However, far from being a passing trend, drama therapy is rooted in more than a century of practice and is supported by robust psychological theories and principles that explain why it works and how it helps.

Theoretical Foundations: Drama therapy stands firmly on three primary psychological frameworks: psychodynamic theory, role theory, and narrative theory.

- Psychodynamic Theory: Drama therapy draws heavily from psychodynamic theory, which emphasizes the existence of an inner, often unconscious life that significantly influences a person’s outward thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Landy, 1986). According to this view, unresolved feelings, hidden conflicts, and unmet needs shape our everyday functioning and wellbeing, often without our awareness. This is the same hidden space where defense mechanisms operate—strategies the mind uses to protect itself from distress. Drama therapy provides a unique pathway to access and process this unconscious material safely through externalization and role-play, helping clients confront and heal these hidden parts of themselves (Landy, 1986).

- Role Theory: Another foundational framework for drama therapy is role theory, which offers the idea that roles are more than just social labels; they are real and tangible expressions of the self (Keisari, 2021). Every person holds multiple roles in life—parent, friend, leader, artist, victim, survivor—and each role carries its own attitudes, behaviors, and emotions. Drama therapy empowers clients to step into, explore, and expand these roles. By experimenting with new roles and re-examining old ones, clients can strengthen positive aspects of their identity and integrate these roles into a more unified, adaptable sense of self (Keisari, 2021).

- Narrative Theory: Drama therapy also draws from narrative theory, which highlights the immense influence that stories have on human experience. People shape their identities and make sense of the world through the stories they hear and the stories they tell themselves about who they are (The Ohio State University College of Arts and Sciences, n.d.). Sometimes, these internal narratives can be limiting, damaging, or outdated. Drama therapy provides a creative space for clients to challenge dominant, unhelpful narratives and to rewrite or reimagine their life stories in empowering ways (Beaudoin, 2005).

Key Principles: Beyond its theoretical foundations, drama therapy is guided by two core principles: catharsis and dramatic reality.

- Catharsis: The concept of catharsis dates back to Aristotle, who described it as the emotional release experienced by audiences of Greek tragedies. This idea remains central to drama therapy today (Moreno, 1940). By acting out difficult experiences or emotions, clients can release long-held tension and unprocessed feelings. This process frees them to move forward with greater emotional lightness and a renewed sense of relief and clarity (Kellerman, 1984).

- Dramatic Reality: Another defining feature of drama therapy is the concept of dramatic reality. This refers to the unique space where everyday reality and imagination intersect—an in-between zone where the real and the fictional merge (Pendzik, 2006). In this protected space, clients can safely explore fears, desires, conflicts, and possibilities without the constraints of ordinary life. Dramatic reality allows them to rehearse new ways of being, experiment with different choices, and gain insights that they can carry back into their day-to-day lives.

Together, these theories and principles make it clear that drama therapy is not simply play for play’s sake. It is a carefully grounded, evidence-informed practice that uses the timeless human tools of story, role, and performance to bring about deep and lasting change.

How to Apply Drama Therapy in Practice:

When people ask how to apply drama therapy, the answer is more nuanced than simply listing a set of steps or techniques. This is because drama therapy isn’t something you just “add” to a session like an activity—it’s an entire therapeutic approach and professional practice that shapes how a therapist works at every stage (Pendzik, 2006). As drama therapist Renée Emunah noted, “As long as we and our clients are involved in dramatic reality, we are doing drama therapy” (Emunah, R., 1994). In other words, if the session uses dramatic reality to help clients explore, express, and transform, then drama therapy is already happening.

- Training and the Therapist’s Role: Only a trained drama therapist can facilitate drama therapy authentically and safely. With professional training, a drama therapist learns to guide clients through a wide range of techniques—some of which come from traditional drama practices, while others are adapted from psychodrama methods. Regardless of the technique, the purpose remains the same: to create a space for dramatic reality and enable catharsis. In doing so, drama therapists help clients break free from rigid thought patterns or emotional blocks that keep them stuck and suffering (Barone, n.d.).

A skilled drama therapist uses their deep understanding of role-play, improvisation, storytelling, symbolism, and embodiment to select or design activities that best serve the client’s goals and needs. Each session is carefully shaped by the therapist’s ability to read the group or individual’s emotional state, respond creatively, and maintain a safe environment for exploration and expression.

- Settings for Drama Therapy: Drama therapy can take place in many different settings—essentially anywhere that offers enough space and privacy for clients to move, speak, and create freely. A conventional therapist’s office can work well, but drama therapy often benefits from more spacious or flexible environments. Sessions may unfold on a small stage in a community theater, in an art studio, or even outdoors, depending on what the therapist and clients need and what supports the work best (Pendzik, 2006).

- Materials Used in Drama Therapy: One of the strengths of drama therapy is that it doesn’t rely on expensive or complicated materials. Much of the work can be done with the simplest and most powerful tool: the human body and voice. However, when helpful, drama therapists may incorporate props, costumes, masks, dolls or puppets, or basic staging elements to deepen the experience. Writing tools for journaling, sound and lighting equipment, or everyday objects that help set a scene can also play an important role. These materials help build atmosphere, support role-play, and evoke emotions in ways that deepen the impact of the session (Pendzik, 2006).

- Ethical Boundaries in Drama Therapy: Working with dramatic reality and role-play introduces unique ethical considerations in addition to the standard responsibilities found in all therapeutic practice. For example, some drama therapy techniques may involve physical contact—like supporting someone in a movement exercise or guiding a role-play that requires gentle touch. The North American Drama Therapy Association (NADTA) Code of Ethical Principles makes it clear that any physical contact must be safe, appropriate, and always with informed consent (North American Drama Therapy Association, n.d.b). Drama therapists are responsible for maintaining clear professional boundaries, managing group dynamics carefully, and ensuring that the creative freedom of dramatic play never compromises a client’s emotional or physical safety.

Subsequently, drama therapy cannot be applied superficially—it is a holistic practice, shaped by the therapist’s training, skill, and commitment to using dramatic techniques to unlock healing through imagination, embodiment, and shared storytelling.

How Effective Is It?

Over the past several decades, research has consistently shown that drama therapy, when delivered by a trained professional and applied thoughtfully, can be a highly effective form of therapy for a wide range of populations and psychological challenges. Just like other established therapeutic approaches, drama therapy has demonstrated strong evidence of its ability to support emotional and social healing, personal growth, and improved quality of life.

Research Highlights on Effectiveness: Multiple studies have confirmed drama therapy’s effectiveness in addressing psychosocial difficulties, helping clients cope with challenges, and supporting emotional regulation. For example, research shows that drama therapy can alleviate psychosocial symptoms and help individuals process internal conflicts and externalize emotions in healthy ways. It also contributes to better coping strategies, emotional regulation, and improved social functioning (Berghs et al., 2022).

Among children, drama therapy has proven especially valuable for developing social skills and reducing social anxiety. One study found that drama therapy interventions significantly improved children’s social skills (Pordanjani, 2021) and helped reduce social anxiety symptoms (Anari et al., 2009). Beyond children’s groups, more recent evidence shows that drama therapy can support a wide range of psychological and behavioral mental health outcomes for both individuals and groups (Orkibi et al., 2023).

Who Can Benefit from Drama Therapy? Drama therapy is remarkably versatile, making it suitable for children, adolescents, adults, and older adults who are experiencing diverse challenges in life. Drama therapists work closely with their clients to tailor sessions to their unique goals and needs. Research and clinical practice show that drama therapy helps people (GoodTherapy, 2015):

- Promote positive behavioral changes

- Develop better interpersonal relationship skills

- Integrate physical and emotional wellbeing

- Achieve deeper personal growth and self-awareness

- Enhance overall quality of life

Applications in Prisons and Correctional Institutions: One striking example of drama therapy’s impact comes from correctional settings. Drama therapy and theater-based programs in prisons have produced impressive results. Inmates who participate in drama therapy often show significant improvements in relationships with peers and authority figures, enhanced communication and social skills, greater self-confidence, and even improved educational outcomes (Gardner et al., 2014). These programs demonstrate how drama’s ability to create “dramatic reality” can help participants safely examine and rewrite harmful patterns of behavior.

Applications in Schools and with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Drama therapy has also shown great promise in schools and with individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In these settings, drama therapy sessions provide children and young people with opportunities to rehearse social interactions, develop friendships, reduce anxiety, and practice flexible thinking and behavior. Research indicates that these sessions help participants feel more connected, supported, and capable of navigating social environments (Godfrey & Haythorne, 2013; McKenna, 2016; Pordanjani, 2021).

Consequently, taken together, the evidence makes clear that drama therapy is far from an experimental or fringe practice—it is an established, adaptable, and evidence-informed approach that helps people of all ages explore their inner worlds, strengthen social connections, and build healthier, more fulfilling lives through the transformative power of drama.

9 Techniques Drama Therapists Use:

Drama therapy is a rich, multifaceted approach that draws deeply from the world of theater to help people express emotions, resolve conflicts, gain insight, and rehearse new ways of being. While there are many creative techniques available to drama therapists, nine core processes capture the essence of how drama therapy facilitates meaningful change (Jones, 1996). These processes blend imagination, embodiment, role-play, and performance to help participants engage with their inner worlds in transformative ways.

- Dramatic Projection: Dramatic projection is a foundational drama therapy technique that gives participants a safe way to project inner thoughts and feelings onto something external — whether a character, prop, or role. This distancing allows clients to explore difficult emotions or conflicts indirectly, which can make it easier to express feelings that might otherwise feel too threatening or overwhelming.

- Personification and Impersonation: Personification and impersonation are closely related but distinct processes. Personification involves expressing personal experiences, emotions, or issues through an object or image — for example, giving voice to a puppet that represents a hidden part of oneself. Impersonation, by contrast, involves embodying a role or character directly through role-play. Both techniques allow participants to safely externalize and examine their inner material.

- Interactive Audience and Witnessing: This process recognizes that being seen, heard, or witnessed is a powerful part of drama therapy. Sometimes clients take the role of the audience, observing another’s enactment and reflecting on it. At other times, the group or therapist witnesses a client’s performance. This dynamic provides validation, fosters empathy, and allows participants to feel supported and understood within a safe space.

- Playing: At the heart of drama therapy is the concept of playing. In this context, play is not trivial — it’s a serious, spontaneous, creative process that encourages problem-solving, experimentation, and freedom. Participants might transform everyday objects into symbolic props, stake out a “play space” for improvisation, or adapt stories in the moment. Playfulness invites flexibility, imagination, and surprise, which are crucial for therapeutic insight and growth.

- Drama-Therapeutic Empathy and Distancing: A key balancing act in drama therapy is knowing when to engage deeply with personal material and when to create emotional distance. This process allows participants to step closer to or further away from sensitive issues, depending on what feels safe and helpful at the time. This balance of empathy and distancing supports both emotional connection and protection from overwhelm.

- Life–Drama Connection: This process emphasizes the link between real-life experiences and dramatic enactment. By analyzing personal problems through dramatic projection — such as acting out a conflict or embodying a fear — clients gain new insights and perspectives that they can carry back into everyday life. This bridge between art and reality is one of drama therapy’s most transformative elements.

- Transformation: Transformation is an inherent part of storytelling and theater. In drama therapy, transformation happens when a participant’s experience shifts — a new understanding emerges, a problem is seen differently, or a stuck pattern is reimagined. This creative shift often happens through the symbolic power of drama, where roles and stories can be rewritten in ways that open up real change.

- Embodiment: Drama therapy is highly physical. Embodiment means expressing thoughts, feelings, or inner conflicts through the body — through posture, gesture, movement, or full-body role-play. By working physically, clients access knowledge and insight that words alone can’t reach. This learning through the body deepens self-awareness and can unlock new paths for healing.

- Therapeutic Performance Processes: Finally, therapeutic performance involves using structured theatrical performances as part of the healing process. Clients may rehearse and perform scenes or stories that reflect their personal themes, struggles, or hopes. This not only provides catharsis but also offers an opportunity for the group or audience to bear witness, which can be incredibly validating and empowering.

Together, these nine core techniques demonstrate how drama therapy goes far beyond simple role-play. It is an intentional, evidence-based blend of play, performance, embodiment, storytelling, and witnessing that opens space for healing and growth in uniquely creative ways.

Engaging Drama Therapy Activities & Exercises for Clients:

It’s important to note that true drama therapy is a professional practice requiring extensive education, supervised clinical training, and certification. It cannot be fully mastered through a few weekend workshops or isolated training courses (Leveton, 2001). However, for counselors, educators, or facilitators who wish to incorporate some creative drama-based techniques into their work — while staying within their scope of practice — there are simple activities inspired by core drama therapy principles that can help clients build emotional awareness, imagination, and self-expression. Below are two engaging examples of such activities, adapted from approaches used in drama therapy:

1. Childhood Play Warm-Up: The Childhood Play Warm-Up is an excellent activity to help clients loosen up, access imagination, and step out of their present-day roles — a key step in drama therapy (Leveton, 2001). This warm-up works well in group sessions but can also be adapted for individual clients.

How it works: Begin by inviting clients to reconnect with a joyful, playful memory from their childhood. The facilitator can use these prompts:

“Think of your favorite game or pastime when you were a child. Imagine yourself playing that game — notice what you looked like, how you sounded, and what was around you. Try to see and feel yourself as you were back then.”

Allow a few minutes for clients to visualize and fully step into that memory.

Next, say:

“Now, staying at the age you just imagined, tell us your name — maybe you had a nickname back then. Remember, we don’t know how old you are or what game you were playing.”

Participants then introduce themselves as their childhood selves. The facilitator encourages gentle conversation within the group, keeping everyone “in character” as their younger selves. This playful exploration helps break down barriers, warm up the imagination, and make clients more comfortable with stepping into different roles — an important part of drama therapy work (Leveton, 2001).

2. Emotion Charades: Emotion Charades is a classic drama-based group activity designed to help clients practice recognizing, expressing, and interpreting emotions — core skills in drama therapy (Leveton, 2001).

How it works: Start by preparing slips of paper, each with a different emotion written on it. Include basic emotions like joy, surprise, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, or worry. For more advanced groups, introduce more nuanced emotions such as relief, tenseness, euphoria, or consternation.

Clients take turns drawing a slip of paper and silently acting out the emotion using only body language and facial expressions — no words or sounds. The rest of the group observes and guesses which emotion is being portrayed.

However, the most meaningful part comes after the guessing. Once the group correctly identifies the emotion, the facilitator leads a short discussion:

- What clues gave it away?

- What body movements, facial expressions, or gestures communicated the feeling?

- How do we notice these cues in real life?

- What was it like to act out that emotion?

This reflective conversation helps deepen clients’ understanding of emotional expression and improves their ability to read nonverbal cues — skills that can be applied in daily life to enhance empathy, communication, and emotional literacy (Leveton, 2001).

A Note of Caution: While activities like these can add value to a group or counseling setting, it’s essential to remember that they are inspired by drama therapy but are not a substitute for working with a certified drama therapist. Facilitators should always stay within their professional scope of practice, use these exercises mindfully, and create a safe, supportive environment where clients feel comfortable exploring and expressing themselves creatively.

How to Become a Drama Therapist:

Becoming a drama therapist is a rewarding journey that combines a solid foundation in mental health or social services with specialized training in drama and theatrical techniques. It’s not a role that someone can step into simply by taking a few acting classes or short workshops. Instead, becoming a drama therapist requires formal education, hands-on clinical practice, and recognized professional certification.

- General Education and Licensing: First and foremost, a person must meet the general educational and licensing requirements for providing therapy in their country or region. This usually means earning an undergraduate degree in a related field such as psychology, counseling, social work, or sociology and then completing any necessary postgraduate training to qualify for professional licensure as a therapist or counselor. After graduation, aspiring therapists typically must pass licensing exams and register with the appropriate regulatory boards or associations in their area (North American Drama Therapy Association, n.d.).

- Prerequisites for Drama Therapy: There are no rigid prerequisites for entering a drama therapy training program beyond this broader educational and licensing background. However, prior experience in drama or theater — whether through academic coursework, community theater, or other creative outlets — is strongly recommended. A basic comfort with acting, improvisation, or creative play gives prospective drama therapists a head start in their advanced training and practice (North American Drama Therapy Association, n.d.).

- Degrees and Specialized Training: To become a Registered Drama Therapist (RDT) through the North American Drama Therapy Association (NADTA), additional specialized training beyond a general therapy degree is required. This training dives deeply into the theories, methods, and ethics specific to drama therapy. There are two primary paths:

- Complete an NADTA-Accredited Master’s Program: Some universities offer accredited master’s degree programs specifically in drama therapy. These programs combine advanced coursework in counseling and psychotherapy with immersive training in drama therapy techniques, supervised clinical practice, and field placements.

- Alternative Route with a Board-Certified Trainer (BCT): For those who already hold a relevant degree but do not attend an accredited master’s program, the NADTA offers an alternative route. This involves undertaking a training program under the direct mentorship of a Board-Certified Trainer (BCT) — an experienced drama therapist who provides individualized instruction, supervision, and guidance to help candidates meet the requirements for RDT credentialing (North American Drama Therapy Association, n.d.).

- Certifications: Upon successful completion of an accredited program or mentorship pathway, aspiring drama therapists can apply for the Registered Drama Therapist (RDT) credential through the NADTA — the main professional certification recognized in North America. Holding this credential demonstrates that the therapist has met the association’s standards for specialized training, ethical practice, and continuing professional development (North American Drama Therapy Association, n.d.).

For anyone interested in learning more about the training process, certification requirements, or finding an accredited program or BCT mentor, the NADTA website provides extensive resources, including up-to-date lists of programs and trainers.

Thus, becoming a drama therapist involves dedication, a genuine passion for the healing power of the arts, and a commitment to integrating therapeutic expertise with creative practice to help clients transform their stories and their lives.

In conclusion, drama therapy opens a powerful pathway for individuals to heal, express their deepest feelings, share their unique stories, and build connections with others — all within a safe, supportive environment guided by trained professionals. This creative form of therapy holds remarkable promise for anyone seeking meaningful change, but it can be especially life-changing for those who most need opportunities for self-expression, healthy interaction, and personal growth.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is drama therapy in simple terms?

Drama therapy is an approach that uses theater techniques like role-play, storytelling, and improvisation to help people express emotions, solve problems, and grow personally.

Who can benefit from drama therapy?

Drama therapy can help people of all ages — children, teenagers, and adults. It’s especially helpful for anyone struggling with stress, anxiety, trauma, social difficulties, or those who find it hard to express themselves through talking alone.

How is drama therapy different from regular talk therapy?

Unlike traditional talk therapy, drama therapy invites people to act out feelings, conflicts, or life situations instead of just talking about them. It’s more active and creative, helping people see problems and solutions from new perspectives.

What happens during a drama therapy session?

A typical session might include warm-up games, improvisation, storytelling, role-playing, and discussion. Sessions are carefully guided to make sure everyone feels safe and supported while exploring emotions and ideas.

Do I need to be good at acting to join drama therapy?

Not at all! No acting experience is needed. Drama therapy is about using imagination and expression — not putting on a perfect performance.

Is drama therapy effective?

Yes. Research and experience show that drama therapy can help people improve social skills, manage anxiety, process difficult experiences, and build emotional awareness and confidence.

Where does drama therapy take place?

Drama therapy can happen anywhere there’s enough space to move, speak, and create — such as therapy rooms, community centers, schools, hospitals, prisons, or even outdoor spaces.

How can someone become a drama therapist?

To become a drama therapist, a person usually needs a degree in a related field, plus specialized training in drama therapy and professional certification.

Is drama therapy safe for everyone?

When provided by a qualified professional, drama therapy is designed to be safe, respectful, and supportive. Therapists follow clear ethical guidelines and ensure that activities like role-play and movement feel comfortable for each participant.

References:

- Anari, A., Ddadsetan, P., & Sedghpour, B. S. (2009). The effectiveness of drama therapy on decreasing of the symptoms of social anxiety disorder in children. European Psychiatry, 24(S1), S514. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(09)70747-3

- Austin, S. F. (1917). Principles of drama-therapy: A handbook for dramatists. Sopherim.

- Barone, P. T. (n.d.). Jacob Levy Moreno and psychodrama. Retrieved April 28, 2025, from https://www.michiganpsychodramacenter.com/jacob-levy-moreno-and-psychodrama/

- Beaudoin, M. (2005). Agency and choice in the face of trauma: A narrative therapy map. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 24(4), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1521/jsyt.2005.24.4.32

- Berghs, M., Prick, A. J. C., Vissers, C., & van Hooren, S. (2022). Drama therapy for children and adolescents with psychosocial problems: A systemic review on effects, means, therapeutic attitude, and supposed mechanisms of change. Children, 9(9), 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091358

- Emunah, R. (1994). Acting for real. Routledge.

- Nicholls, K. (2024). Dramatherapy. Retrieved June 14, 2025, from https://www.counselling-directory.org.uk/drama-therapy.html

- Gardner, A., Hager, L. L., & Hillman, G. (2014). Prison arts resource project: An annotated bibliography. National Endowment for the Arts: Art Works Program. Retrieved from http://www.artsevidence.org.uk/media/uploads/prisonartsresourceprojectmarch2016.pdf

- Giacomucci, S., & Marquit, J. (2020). The effectiveness of trauma-focused psychodrama in the treatment of PTSD in inpatient substance abuse treatment. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 896. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00896

- Godfrey, E., & Haythorne, D. (2013). Benefits of dramatherapy for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A qualitative analysis of feedback from parents and teachers of clients attending Roundabout dramatherapy sessions in schools. Dramatherapy, 35(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02630672.2013.773131

- (2015). Drama therapy. Retrieved June 14, 2025, from https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/drama-therapy

- Haen, C., & Weber, A. N. (2005). Clinical applications of drama therapy in child and adolescent treatment. Routledge.

- Jones, P. (1996). Drama as therapy: Theatre as living. Routledge.

- Keisari, S. (2021). Expanding the role repertoire while aging: A drama therapy model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635975

- Kellerman, P. F. (1984). The place of catharsis in psychodrama. Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama and Sociometry, 37(1), 1–13.

- Landy, R. J. (1986). Drama therapy concepts and practices. Charles C. Thomas.

- Landy, R. J. (1994). Drama therapy concepts and practices (2nd ed.). Charles C. Thomas.

- Langley, D. (2006). An introduction to dramatherapy. Sage.

- Leveton, E. (2001). A clinician’s guide to psychodrama. Springer Publishing Company.

- McKenna, L. (2016). Boosting social skills in autistic kids with drama. The Atlantic. Retrieved June 14, 2025, from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/06/boosting-social-skills-in-autistic-kids-with-drama/485027/

- Moreno, J. L. (1940). Mental catharsis and the psychodrama. Sociometry, 3(3), 209–244. https://doi.org/10.2307/2785151

- North American Drama Therapy Association. (n.d.a). About NADTA. Retrieved April 28, 2025, from https://www.nadta.org/about-nadta

- North American Drama Therapy Association. (n.d.b). NATDA code of ethical principles. Retrieved April 28, 2025, from https://www.nadta.org/assets/code%20of%20ethics.pdf

- Orkibi, H., & Feniger-Schaal, R. (2019). Integrative systematic review of psychodrama psychotherapy research: Trends and methodological implications. PloS ONE, 14(2), e0212575. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212575

- Orkibi, H., Keisari, S., Sajnani, N. L., & de Witte, M. (2023). Effectiveness of drama-based therapies on mental health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000582

- Pendzik, S. (2006). On dramatic reality and its therapeutic function in drama therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 33(4), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2006.03.001

- Pordanjani, S. R. (2021). Effectiveness of drama therapy on social skills of autistic children. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.32598/jpcp.9.1.344.2

- The Ohio State University College of the Arts and Sciences. (n.d.). What is narrative theory? Retrieved April 28, 2025, from https://projectnarrative.osu.edu/about/what-is-narrative-theory

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College