Basic Concept of Self-actualization:

The idea of becoming the best version of oneself has fascinated philosophers, psychologists, and everyday people for generations. One of the most influential figures to give this idea a formal shape was Abraham Maslow, who introduced the concept of self-actualization as the pinnacle of his famous “hierarchy of needs.” While the term is now more familiar to many, it is still often studied in the context of Maslow’s work, remaining a central theme in psychology courses and discussions about human potential. This article explores the basic concept of self-actualization, highlights key research findings, and examines how this concept continues to inspire both the positive psychology movement and individuals striving for a more fulfilling life.

What is Self-Actualization?

While many people immediately connect the idea of self-actualization with Abraham Maslow and his well-known hierarchy of needs, it is important to recognize that the term actually originated with the German neurologist and psychiatrist Kurt Goldstein. Goldstein introduced self-actualization as a central concept in his holistic approach to understanding human behavior. He described it as an individuation process — a journey through which a person becomes fully themselves. According to Goldstein, self-actualization is not just about personal growth in isolation but about recognizing that the self and the environment are parts of a larger, interconnected whole. He argued that this striving to become one’s fullest self serves as a fundamental driving force behind human behavior (Whitehead, 2017).

Despite the innovative nature of Goldstein’s perspective, his ideas did not gain widespread acceptance at the time. The concept only began to reach mainstream awareness when Abraham Maslow expanded upon it in the mid-20th century. Maslow integrated self-actualization as the highest level of his influential hierarchy of needs, which he presented in his groundbreaking paper on human motivation. In his own words, Maslow explained this idea with the famous statement, “What a man can be, he must be. This need we may call self-actualization” (Maslow, 1943). This succinct phrase captures Maslow’s belief that the desire to fulfill one’s ultimate potential is an innate and powerful human need that emerges once more basic physical and psychological needs have been satisfied.

Over time, other scholars have also contributed to refining and clarifying the definition of self-actualization. For example, Couture and colleagues (2007) described it as the psychological process aimed at maximizing the use of a person’s abilities and resources. They noted that this process is highly individualized, meaning that how one person experiences or pursues self-actualization may look entirely different from another person’s journey. This emphasis on personal uniqueness aligns with Maslow’s view that motivation is deeply rooted in each person’s individual characteristics, values, and capacities.

In essence, self-actualization is about realizing and expressing one’s full creative, intellectual, and social potential — not for external validation or rewards such as wealth, power, or social status, but driven by an inner desire to grow, create, and contribute meaningfully. This inward focus on maximizing one’s talents and possibilities remains a key feature of humanistic psychology and continues to inspire people seeking to live authentic and fulfilling lives.

The Theory of Self-Actualization and the Hierarchy of Needs:

Abraham Maslow’s concept of self-actualization is deeply rooted in his broader framework known as the hierarchy of needs, which remains one of the most influential theories in psychology. To fully appreciate what self-actualization means and how it works, it is essential to understand how Maslow positioned it within the larger structure of human motivation.

Maslow believed that mainstream psychology at the time was too focused on behaviorism, which primarily studied how animals and humans respond to external stimuli and reinforcement. He argued that this approach overlooked what makes humans unique: our capacity for growth, meaning, and fulfillment beyond basic drives. Maslow strongly felt that the study of “[m]otivation should be human-centered rather than animal-centered” (Maslow, 1943). In other words, he urged psychologists to consider what drives people to strive for personal growth, purpose, and self-betterment — not just what prompts basic behaviors.

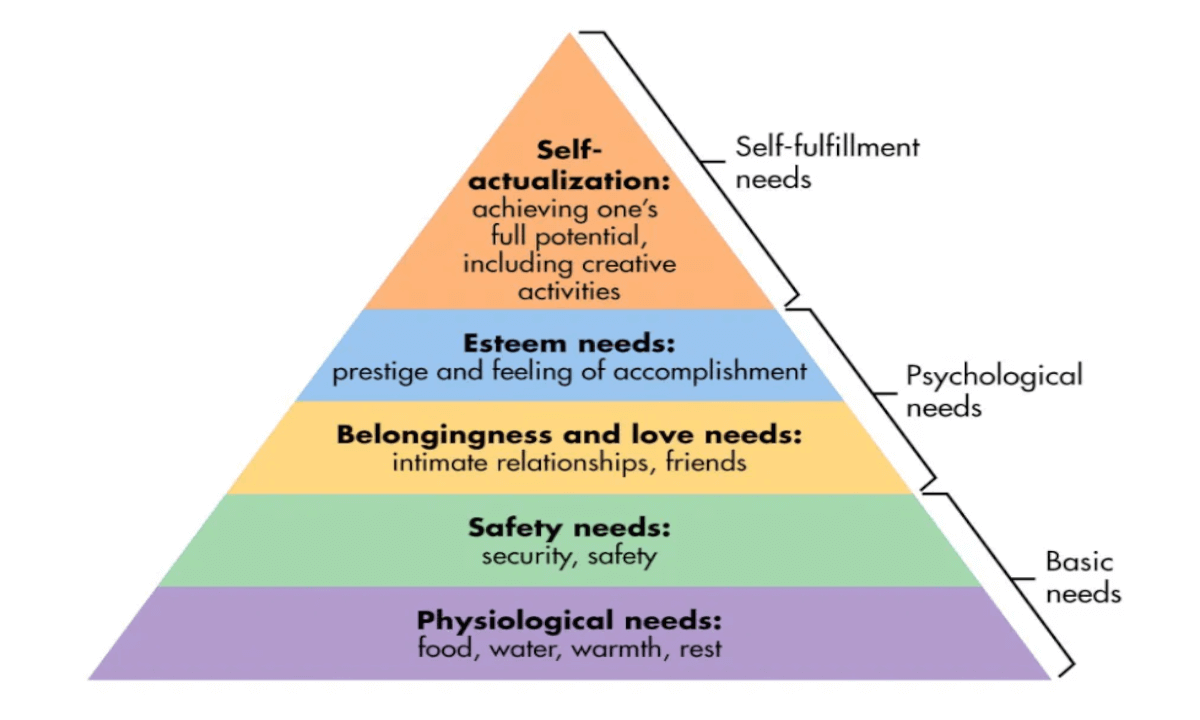

In his groundbreaking 1943 paper on human motivation, Maslow laid out his famous hierarchy of needs, presenting it as a pyramid with five distinct levels. He theorized that human needs are organized in a progression from basic survival needs to higher psychological and self-fulfillment needs. These five levels are:

- Physiological Needs — These are the most fundamental requirements for humagn survival, including necessities like air, food, water, and sleep. Without these, none of the higher needs can be meaningfully pursued.

- Safety Needs — Once physiological needs are reasonably satisfied, people naturally focus on feeling secure and safe. This can mean having reliable shelter, access to healthcare, clean water, or living in an environment where one feels protected from harm.

- Love and Belongingness Needs — When people feel physically safe and healthy, their attention shifts to emotional and social needs. These include forming meaningful relationships, feeling liked and loved, and experiencing a sense of belonging within a family, peer group, or community.

- Esteem Needs — At this level, people desire to feel confident, competent, and respected by others. Esteem needs include both self-esteem (feeling good about oneself) and the esteem received from others (recognition, status, or respect).

- Self-Actualization Needs — Sitting at the peak of the hierarchy is self-actualization, which refers to the ongoing process of realizing and fulfilling one’s potential through personal growth and self-development. According to Maslow, this is the point where a person seeks to become everything they are capable of becoming — whether through creativity, problem-solving, moral development, or other forms of self-expression and mastery.

Maslow theorized that individuals must generally satisfy needs at one level before moving on to focus on the next. For instance, someone struggling to find food and shelter will be more concerned about survival than about gaining social acceptance or pursuing personal growth. This progression helps explain why self-actualization, as a higher-level need, typically emerges only when a person’s basic physiological, safety, love, and esteem needs are reasonably secure.

However, Maslow did recognize that the order of needs is not always rigid. Life is complex, and there are instances where people may meet some higher-level needs even while lacking lower-level ones. For example, it is not unheard of for individuals experiencing homelessness to find meaning, self-expression, or a sense of purpose in creative work, social activism, or spiritual growth despite severe struggles with basic needs. Nevertheless, Maslow’s general idea still resonates: when basic survival is threatened, most people will naturally prioritize it over fulfilling abstract or self-enhancing goals (Maslow, 1943).

At its core, this framework offers an intuitive understanding of why the journey toward self-actualization is not equally accessible to everyone at all times. It reminds us that before we can focus on becoming the best versions of ourselves, we must have a foundation of physical and emotional security from which to grow.

Examples of Self-Actualization:

Understanding the definition of self-actualization is one thing, but seeing how it plays out in real life makes the concept much clearer and more meaningful. When Abraham Maslow first described self-actualization, he illustrated it vividly by saying, “[a] musician must make music, an artist must paint, a poet must write, if he is to be ultimately happy” (Maslow, 1943). This quote highlights that true fulfillment comes from doing what one feels innately driven to do — not for external rewards or recognition, but because it brings a deep sense of purpose and satisfaction.

Building on Maslow’s idea, we can spot countless everyday examples of self-actualization in action. Consider, for instance, an artist who may never sell a painting or gain fame, but continues to paint simply because creating art makes him feel alive and true to himself. Or think of a woman who dedicates countless hours to mastering a niche hobby, not to show it off, but because the process itself is deeply rewarding. A father raising his children to grow into compassionate, capable adults may also feel a profound sense of purpose and fulfillment, as might an employee at a nonprofit who continually hones her skills to make a real difference in the lives of others. Each of these people is motivated by an inner drive to express their best selves — a hallmark of self-actualization.

When Maslow explored the idea more deeply in his later writings, he even suggested some well-known historical figures whom he believed embodied self-actualization through their life’s work and values. These included influential people like Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, Jane Addams, William James, Albert Schweitzer, Aldous Huxley, and Baruch Spinoza (Maslow, 1970). Interestingly, Maslow did not limit his list to scientists or politicians alone. He also mentioned a diverse range of thinkers, writers, activists, and reformers such as Eugene Debs, Frederick Douglass, Ida Tarbell, Harriet Tubman, George Washington, George Washington Carver, and Walt Whitman.

What stands out in Maslow’s examples is that there is no single path or profession that guarantees self-actualization. Instead, each person reached their potential in their unique way, driven by a commitment to their ideals, passions, or contributions to society. This broad mix of public figures — from poets and philosophers to abolitionists and social reformers — shows that self-actualization is not about fitting a mold, but about realizing one’s individual potential, whatever form that may take.

In recent years, researchers have also explored how people today perceive self-actualization. For example, a study by Krems et al. (2017) found that people often associate realizing their full potential with achieving both esteem and status. The study revealed that “lay perceptions of realizing one’s full potential are linked to the fundamental motive of achieving status and esteem.” In other words, people tend to connect the idea of becoming their best selves with both feeling good about themselves and being recognized by others.

This perspective differs somewhat from Maslow’s original view, where he clearly separated esteem and status needs (which sit below self-actualization on his hierarchy) from self-actualization itself (Maslow, 1943). However, as Krems and colleagues point out, this does not necessarily contradict Maslow’s theory altogether. Some researchers, like Kenrick et al. (2010), have argued for a “functional reading” of Maslow’s hierarchy, which suggests that the behaviors involved in pursuing one’s full potential are often linked to status, either directly or indirectly (Krems et al., 2017).

This does not mean that self-actualization requires fame or external accolades. Rather, it highlights the reality that for many people, feeling respected and valued by others can help support or reflect their journey of self-growth. The essence of self-actualization remains deeply personal and internal — about becoming who you truly are and doing what you are uniquely capable of doing — even if the path toward it sometimes intersects with outward success and recognition.

Altogether, these examples and insights remind us that self-actualization is not a single, rigid goal, but an ongoing process that can take countless forms, shaped by each person’s talents, values, circumstances, and inner calling.

Self-Actualization and Positive Psychology:

The concept of self-actualization ties into positive psychology through its connection with wellbeing; as you might imagine, those who are considered self-actualized are also generally high in wellbeing.

According to Bernard et al. (2010), the work of another renowned humanistic psychologist, Albert Ellis, indicated that “self-actualization involves the pursuit of excellence and enjoyment; whichever people choose to desire and emphasize.”

This focus on excellence and enjoyment as a symptom of the realization of potential explains the link between self-actualization and wellbeing; if reaching your full potential is enjoyable and fulfilling, it logically follows that wellbeing will also be positively affected.

Multiple studies within the field of positive psychology have examined self-actualization as a component of wellbeing (Compton, 2001; Kim et al., 2003), suggesting that it’s a topic that is perfectly at home amongst the other popular positive topics.

Another more recent study examined the effects of a positive psychology course on wellbeing and found that college students who took a course on positive psychology reported increased levels of happiness, hope, mindfulness, and self-actualization, providing correlative evidence of at least some sort of relationship between positive psychology and self-actualization (Maybury, 2013).

Aside from wellbeing, one of the main drives behind founding positive psychology was the reinstatement of a “fundamental [misson] of psychology” that Martin Seligman felt had been too long ignored by contemporary psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

This mission that Maslow highlighted was the goal of “nurturing genius;” since nurturing genius can logically be viewed as a precursor (and companion to) self-actualization and reaching one’s potential, this indicates that self-actualization is comfortably nestled within the field of positive psychology.

Conclusion: In revisiting Abraham Maslow’s influential theory of motivation and his iconic hierarchy of needs, it becomes clear that self-actualization is far more than just a theoretical idea tucked away at the top of a pyramid — it is a deeply personal and practical goal that continues to inspire both individuals and the field of positive psychology (Maslow, 1943; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Not only does striving for self-actualization encourage us to tap into our creative, intellectual, or social potential, but it also serves as a vital pathway to greater wellbeing and fulfillment (Compton, 2001; Kim et al., 2003).

Understanding that self-actualization is not about chasing external rewards like wealth or status but about pursuing what brings true meaning and satisfaction can transform how we live our daily lives. Whether it means painting, teaching, innovating, or nurturing others, the process of realizing our fullest potential is within reach for anyone willing to explore it.

If we embrace Maslow’s vision — and the broader aims of positive psychology — we are reminded that nurturing our strengths and passions is not just good for us as individuals but also contributes to a healthier, more flourishing society (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). As Bernard et al. (2010) put it, when we aim for excellence and enjoyment in whatever we choose to pursue, we take meaningful steps toward both self-actualization and wellbeing.

Ultimately, the journey to self-actualization is a personal one — and each of us must define what it looks like for ourselves. By reflecting on where our true interests and abilities lie, and by cultivating the courage to follow them, we honor the timeless idea that “what a man can be, he must be” (Maslow, 1943).

So, take the time to ask yourself: What does self-actualization mean to you? What dreams are worth pursuing simply because they make you feel most alive? In exploring these questions, you may find that the path to self-actualization is not a distant peak, but a journey you can begin today.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What exactly is self-actualization?

Self-actualization is the journey of becoming the most authentic and fully developed version of yourself. It’s about using your unique strengths, talents, and interests in ways that feel deeply meaningful and satisfying. Rather than chasing external rewards like wealth, fame, or recognition, self-actualization is driven by an inner need to grow, create, and live in line with your true self. When you are self-actualizing, you feel that you’re doing what you’re genuinely meant to do — whether that’s making music, teaching others, solving problems, or caring for people you love.

Is self-actualization the same for everyone?

Not at all. Self-actualization is a very personal process and can look completely different from one person to another. For example, one person might feel most fulfilled writing novels that nobody else ever reads, simply because the act of writing brings them alive. Another might find it through parenting, volunteering, inventing something useful, or mastering a craft or sport. There is no single path — what matters is that it resonates with your passions and feels true to who you are.

How does self-actualization connect to positive psychology?

Positive psychology is the scientific study of what makes life most worth living — things like happiness, purpose, strengths, hope, and resilience. Self-actualization fits naturally within this because it’s all about realizing your deepest potential and living a life that feels rich with meaning and growth. People who pursue self-actualization often find that they also experience greater wellbeing, because they are doing things that align with their values and bring them real joy.

Can you reach self-actualization if your basic needs aren’t met?

In general, it’s easier to focus on personal growth when you have your basic needs met — like having enough to eat, feeling safe, and having supportive relationships. If you’re constantly worried about survival or safety, it can be harder to concentrate on big dreams or personal growth. However, life is messy, and there are plenty of examples of people who have pursued meaningful goals, art, activism, or spiritual growth even in very difficult circumstances. So, while it helps to have a stable foundation, the human spirit can sometimes find ways to grow in surprising places.

Does self-actualization guarantee lifelong happiness?

Not exactly — it’s not a magic formula for constant happiness. Self-actualization often brings a deep sense of purpose, satisfaction, and inner peace, but the journey can also be challenging. You may face obstacles, doubts, or sacrifices along the way. The key difference is that when you’re striving for self-actualization, even setbacks can feel meaningful because they are part of becoming who you truly want to be. So while you won’t feel perfect happiness every day, your life may feel richer and more authentic overall.

How can I work toward self-actualization in my own life?

A good first step is to spend time reflecting on what really matters to you — what activities make you lose track of time, what challenges excite you, or what goals feel worthwhile even if nobody else notices them. Once you have an idea, start setting small, meaningful goals and carve out time for what inspires you. Pay attention to your strengths, stay open to learning, and surround yourself with supportive people when you can. Journaling, mindfulness, and talking with trusted friends or mentors can also help you stay true to your own path. Remember, self-actualization is not about perfection — it’s about progress and staying connected to what feels real and fulfilling for you.

Is self-actualization the same as being successful?

It’s easy to confuse the two, but they’re not the same. Many people see success as having money, titles, awards, or social status. Self-actualization is more about your inner sense of accomplishment — knowing that you are living in line with who you really are and doing what you feel you’re meant to do. Sometimes this overlaps with external success, but it doesn’t have to. For example, a teacher who loves inspiring students may feel deeply self-actualized even without fame or wealth. It’s about feeling whole and true to yourself, regardless of how the outside world measures your achievements.

References:

- Bernard, M.E., Froh, J.J., DiGiuseppe, R., Joyce, M.R., Dryden, W. (2010). Albert Ellis: Unsung hero of positive psychology. Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(4), 302-310. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.498622

- Compton, W.C. (2001). Toward a tripartite factor structure of mental health: Subjective well-being, personal growth, and religiosity. Journal of Psychology, 135(5), 486-500. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980109603714

- Couture, M., Desrosiers, J., Leclerc, G. (2007). Self-actualization and poststroke rehabilitation. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 30(2), 111-117. https://doi.org/10.1097/mrr.0b013e32813a2ea5

- Frick, W.B. (2000). Remembering Maslow: Reflections on a 1968 interview. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 40(2), 128-147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167800402003

- Goud, N. (2008). Abraham Maslow: A personal statement. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 48(4), 448-451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167808320535

- Hoffman, E. (2008). Abraham Maslow: A biographer’s reflections. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 48(4), 439-443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167808320534

- Kenrick, D.T., Neuberg, S.L., Griskevicius, V., Becker, D.V., Schaller, M. (2010). Goal-Driven Cognition and Functional Behavior: The Fundamental-Motives Framework. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 63-67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721409359281

- Kim, Y., Kasser, T., Lee, H. (2003). Self-concept, aspirations, and well-being in South Korea and the United States. Journal of Social Psychology, 143(3), 277-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540309598445

- Krems, J.A., Kenrick, D.T., Neel, R. (2017). Individual Perceptions of Self-Actualization: What Functional Motives Are Linked to Fulfilling One’s Full Potential? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(9), 1337-1352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217713191

- Maslow, A.H. (1970). Motivation and Personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

- Maybury, K.K. (2013). The Influence of a Positive Psychology Course on Student Well-Being. Teaching of Psychology, 40(1), 62-65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628312465868

- Seligman, M.E.P., Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology – An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5

- Whitehead, P. M. (2017). Goldstein’s self-actualization: A biosemiotic view. The Humanistic Psychologist, 45(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/hum0000047

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College