Basic Concept of Self-Confidence:

Over the past five decades, the idea of self-confidence as a cornerstone of personal development and achievement has gained remarkable grip in Western society. From classrooms to parenting strategies, there has been a growing emphasis on nurturing self-belief as a means to unlock potential and foster success (Baskin, 2011). This cultural shift was sparked by psychologist Nathaniel Branden’s groundbreaking work in 1969, where he suggested that many emotional and psychological difficulties could be traced back to low self-esteem. According to Branden, enhancing an individual’s self-worth could not only improve performance but also address deeper psychological issues, laying the groundwork for what would later become known as the Self-Esteem Movement. Since then, the connection between self-esteem and success has been the subject of extensive research and public interest, spanning academic studies and popular discourse. Yet, while the conversation around self-esteem continues to grow, it is important to recognize that terms like self-efficacy, self-confidence, and self-esteem are often used interchangeably—despite representing distinct psychological constructs. Before diving into the nuanced nature of self-esteem, it is crucial to clarify these overlapping ideas to gain a clearer understanding of how belief in oneself truly shapes the human experience. As poet E.E. Cummings once expressed, “Once we believe in ourselves, we can risk curiosity, wonder, spontaneous delight, or any experience that reveals the human spirit.” In the rest of this article, we will explore the basic concept of self-confidence.

Defining the Difference (Self-Efficacy, Self-Confidence, and Self-Esteem):

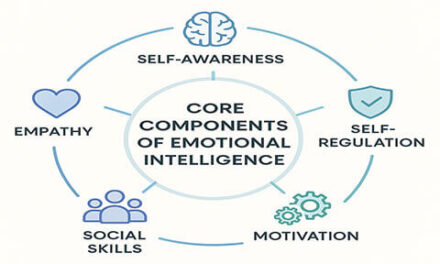

Many people casually use the terms self-confidence and self-esteem interchangeably, while the concept of self-efficacy is often overlooked altogether. However, psychologists and researchers have made important distinctions among these terms, as each reflects a unique aspect of how we perceive ourselves (Druckman & Bjork, 1994; Oney & Oksuzoglu-Guven, 2015). Understanding these differences can help us better grasp our own psychological makeup and the ways in which we pursue goals, face challenges, and evaluate our self-worth.

What is Self-Efficacy?

The concept of self-efficacy was introduced by psychologist Albert Bandura, one of the most prominent scholars in this field. He defined self-efficacy as an individual’s belief in their ability to exert control over their own functioning and over events that affect their lives (Bandura, 1977). In other words, it refers to the confidence we have in our ability to succeed in specific situations or accomplish particular tasks.

What makes self-efficacy distinct is its forward-looking nature—it focuses on what we believe we can do in the future. This is different from self-esteem, which deals more with how we feel about ourselves in general. While self-esteem is often concerned with feelings of worthiness or personal value, self-efficacy is about believing that we can successfully handle what lies ahead. A person may have high self-efficacy in a certain area (e.g., public speaking or problem-solving) even if they don’t always feel highly about themselves overall. Thus, while related, these two concepts play different roles in shaping our motivation and behavior.

What is Self-Confidence?

Among the three terms, self-confidence is the most frequently used in everyday conversation, but ironically, it’s also the least clearly defined. Generally, self-confidence refers to a person’s belief in their own abilities. According to Bénabou and Tirole (2002), it can be understood simply as “believing in oneself.”

A deeper psychological perspective, as proposed by Lenney (1977), defines self-confidence as the combination of an individual’s expectations of performance and their self-assessment of ability based on past experiences. Meanwhile, Psychology Dictionary Online offers a broader view, describing self-confidence as trust in one’s own capacities, judgments, and abilities to deal effectively with life’s challenges.

In essence, self-confidence can be seen as a bridge between past achievements and future expectations. People who are confident tend to be happier and more resilient because their past experiences have shown them that they are capable of overcoming obstacles. This sense of competence energizes them and motivates further action, increasing their likelihood of success.

While self-efficacy is often linked to a specific skill or context, self-confidence tends to be more generalized and stable. It reflects not just the belief in one’s capabilities but also a certain level of emotional assurance that they can handle life’s demands broadly.

What is Self-Esteem?

Self-esteem refers to the overall subjective evaluation of one’s worth or value as a person. It is a deeply rooted belief system that influences how we feel about ourselves and our place in the world. Two of the most influential voices in the study of self-esteem are Morris Rosenberg and Nathaniel Branden.

Rosenberg, in his landmark 1965 book Society and the Adolescent Self-Image, defined self-esteem as a relatively stable sense of one’s own worth. His Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale remains one of the most widely used instruments in psychological research to measure this trait.

Nathaniel Branden, on the other hand, offered a more nuanced understanding of self-esteem. He proposed that self-esteem consists of two critical components: self-efficacy—the belief in our ability to cope with life’s challenges—and self-respect—the belief that we deserve happiness, love, and success (Branden, 1969). While both Branden and Rosenberg agree that self-esteem is central to psychological health, Branden’s breakdown of its components provides a clearer pathway for developing and maintaining it.

An important point to consider is that having too much self-esteem can be problematic. Excessively high self-esteem may lead to narcissism, which is marked by an inflated sense of self-importance and an insatiable need for admiration. Psychologically, narcissism is considered an extreme manifestation of self-focus, where one’s own abilities and value are grossly exaggerated.

Therefore, balance is key. The healthiest form of self-esteem is both realistic and positive—a sense of self-worth that acknowledges one’s strengths while remaining aware of limitations. This balanced view allows individuals to grow and thrive without slipping into arrogance or self-doubt.

Where Does Self-Esteem Come From?

Self-esteem is often considered a personality trait, meaning it is generally stable over time, but that doesn’t mean it’s completely immune to change. It develops from early experiences, social interactions, and internal beliefs. Typically, self-esteem arises from a combination of:

- Basic human need – Self-esteem is essential for healthy development and overall well-being.

- Internal origin – It grows from within, based on personal beliefs and self-awareness.

- Interconnectedness – It is influenced by a person’s thoughts, emotions, actions, and behaviors.

Furthermore, Abraham Maslow placed self-esteem within his hierarchy of needs, recognizing it as a fundamental requirement for reaching self-actualization—the realization of one’s full potential. According to Maslow, people need both external validation (respect and recognition from others) and internal self-respect to develop a healthy sense of self-esteem.

While self-efficacy, self-confidence, and self-esteem are related, they represent different layers of how we perceive and evaluate ourselves. Self-efficacy is task-specific and future-oriented. Self-confidence is broader, connecting past experiences to future performance. Self-esteem is the deepest of the three, tied to a general sense of worth and identity. By understanding these subtle but important distinctions, we become better equipped to work on personal development in a more targeted and meaningful way—nurturing not just belief in our abilities, but also cultivating a deep sense of value and purpose.

Popular Theories of Self-Confidence:

With a clear understanding of how self-efficacy, self-confidence, and self-esteem differ, we can now explore the most prominent psychological theories that seek to explain how these traits develop and function in our lives. Over the years, various psychologists have attempted to understand self-confidence and self-esteem through different theoretical lenses. While Nathaniel Branden’s work laid important groundwork in defining and promoting the concept of self-esteem, other psychologists have offered complementary—and sometimes contrasting—perspectives that enrich our understanding of these inner experiences.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs:

One of the earliest and most widely recognized frameworks to address self-esteem and self-confidence comes from Abraham Maslow. In his influential theory introduced in 1943, Maslow outlined a five-tier model of human needs, often depicted as a pyramid, with each level representing a different category of psychological and physiological requirements for personal growth (Maslow, 1943).

At the base of the pyramid are the most fundamental needs—physiological needs (such as food, water, and shelter) and safety needs. Once those are fulfilled, individuals can then focus on love and belonging, followed by self-esteem, which Maslow placed as the second highest level of need—just below self-actualization.

Maslow further divided self-esteem into two categories:

- Lower self-esteem, which comes from external sources such as recognition, respect, and status from others.

- Higher self-esteem, which arises internally from within the individual and is characterized by feelings of self-worth, competence, and autonomy.

Originally, Maslow argued that people must first satisfy the lower needs (like food, safety, and love) before they can move on to higher levels like self-esteem and self-actualization. However, in his later work, he acknowledged exceptions to this structure. For instance, he noted that certain individuals—like homeless people who possess strong self-belief or those living in war zones—could still display high levels of self-esteem and even self-actualization, despite their unstable environments.

Today, psychologists tend to view Maslow’s hierarchy less as a rigid, step-by-step model and more as a flexible framework that helps explain how meeting basic needs supports the pursuit of more complex psychological growth.

Terror Management Theory (TMT):

While Maslow’s theory takes a more optimistic view of human growth, Terror Management Theory (TMT) introduces a darker but equally compelling psychological explanation for self-esteem. TMT is rooted in existential psychology and was developed by Greenberg and Arndt to explore how human beings cope with the fear of death (Greenberg & Arndt, 2011).

The theory suggests that people, uniquely aware of their own mortality, are susceptible to profound existential anxiety or “terror.” To manage this terror, individuals adopt worldviews—religious, cultural, or philosophical belief systems—that offer meaning, order, and permanence. Within these worldviews, self-esteem functions as a psychological buffer, giving people the feeling that they are valuable contributors to something greater and more enduring than themselves.

According to TMT, when our self-confidence or belief systems are threatened (for instance, when someone criticizes our religion, political views, or personal identity), we may respond defensively—often by devaluing others, withdrawing, or aggressively reaffirming our worldview. In this light, self-esteem is not only a measure of self-worth but also a protective mechanism that shields us from the fear of our own impermanence.

TMT’s unique contribution lies in showing that self-confidence may serve a deep survival function, helping us maintain emotional stability in the face of our most fundamental fears.

Sociometer Theory:

Another highly influential theory in the domain of self-esteem is the Sociometer Theory, developed by social psychologist Mark Leary. Unlike Maslow and TMT, which focus on internal needs and existential fear, Sociometer Theory proposes that self-esteem is inherently social in nature.

According to Leary (2006), self-esteem functions as an internal “sociometer”—a psychological gauge that monitors the degree to which we are accepted or rejected by others. The theory posits that our brains are wired to constantly scan our social environments for cues about how we are being perceived, and this feedback directly influences our self-esteem.

In support of this theory, Leary and his colleagues found that people’s changes in self-esteem tend to correlate closely with how they predict others will react to them. For instance, when individuals anticipate rejection or exclusion, their self-esteem tends to decrease, even before any explicit social feedback is received (Leary, Tambor, Terdal, & Downs, 1995). Moreover, actual experiences of social exclusion—especially those based on personal characteristics—have been shown to significantly lower self-esteem (Leary et al., 1995).

What sets Sociometer Theory apart is its evolutionary perspective. It suggests that our ancestors depended on social groups for survival, and thus, self-esteem evolved as a tool to help us maintain social bonds. In this view, self-confidence is not just about personal belief or ability, but about our perceived standing in the social world.

The field of psychology offers a rich and diverse set of theories to help explain the nature and function of self-confidence and self-esteem. From Maslow’s emphasis on personal growth and intrinsic needs, to TMT’s focus on existential fear, to Leary’s socially driven sociometer model, each framework captures a different aspect of the complex human experience of believing in oneself. Taken together, these theories remind us that self-confidence is not just a simple feeling—it is shaped by our inner beliefs, our social interactions, and even our awareness of mortality. Whether we’re striving for self-actualization, seeking social inclusion, or defending against anxiety, our sense of self plays a powerful role in how we navigate the world and pursue our goals.

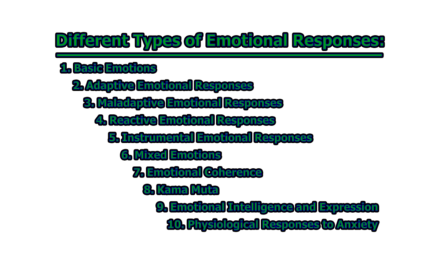

The Importance of Self-Confidence:

“Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson

Self-confidence plays an essential role in nearly every area of life. Whether you subscribe to Maslow’s hierarchy, Branden’s model of self-esteem, or Leary’s sociometer theory, one truth remains constant across psychological literature: higher self-confidence is consistently associated with a broad range of positive life outcomes. Researchers widely agree that individuals who possess high levels of self-confidence experience numerous benefits across physical health, mental well-being, relationships, and overall life satisfaction.

The Broad Impact of Self-Confidence on Life Outcomes: A comprehensive review of the correlates of self-esteem by Mann, Hosman, Schaalma, and de Vries (2004) found compelling evidence that high self-confidence and self-esteem are strongly linked to improved health outcomes, stronger social connections, and better psychological resilience. For example, individuals with high self-esteem are more likely to:

- Have better overall health, including stronger immune functioning.

- Enjoy more meaningful social relationships and support systems.

- Be less vulnerable to mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety.

- Demonstrate better coping mechanisms in response to stress and adversity.

- Exhibit stronger psychological well-being, including emotional stability and a positive outlook on life.

Moreover, these benefits appear early and extend throughout the lifespan. Children with higher self-confidence tend to perform better academically, engage more actively in the classroom, and feel more secure in peer interactions. Later in life, these individuals report greater job satisfaction and more fulfilling careers, particularly in middle age (Mann et al., 2004). Importantly, high self-confidence is not only about professional success—it also enhances quality of life. One striking study even found that self-confidence could increase the chances of survival after a major surgical procedure, likely due to the psychological impact on recovery and resilience (Mann et al., 2004).

Self-Confidence and Happiness: Another major area where self-confidence exerts influence is in subjective well-being. Numerous studies suggest a robust relationship between high self-esteem and happiness. Individuals who view themselves positively are more likely to feel content, optimistic, and energized. High self-confidence often translates into greater motivation, stronger goal-setting behavior, and a deeper sense of purpose (Atherton et al., 2016; Gloppen, David-Ferdon, & Bates, 2010; Clark & Gakuru, 2014).

Psychological studies have identified several attributes that are commonly found in individuals with high self-confidence (Skenderis, 2015; Stankov, 2013; Stankov & Lee, 2014):

- A Greater Sense of Self-Worth: People who feel confident believe in their intrinsic value and feel deserving of respect and success.

- More Enjoyment in Life and Activities: Self-confident individuals tend to engage more fully with life, taking pleasure in both work and leisure.

- Freedom from Self-Doubt: While they may still face challenges, they trust in their ability to handle setbacks and learn from failure.

- Reduced Anxiety and Stress: Higher self-confidence correlates with lower levels of social anxiety and stress, contributing to mental peace and emotional resilience.

- Increased Energy and Motivation: Confidence fuels action—those who believe in their potential are more likely to take initiative and pursue goals with vigor.

- More Positive Social Interactions: Confident people are more relaxed in social settings, which puts others at ease and fosters stronger interpersonal connections.

Caution (The Double-Edged Sword of Self-Confidence): Despite the many benefits of self-confidence, some researchers urge caution. Boosting self-confidence indiscriminately may not always result in positive outcomes, especially when confidence becomes inflated or detached from actual ability. For example, Brinkman et al. (2015) and Forsyth et al. (2007) argue that simply increasing a person’s belief in themselves doesn’t always improve performance. In some cases, it can lead to overconfidence, complacency, or resistance to feedback—undermining growth instead of supporting it.

There is also concern from cultural critics and some psychologists about the unintended consequences of the self-esteem movement, especially in Western societies. As Kremer (2013) points out, while average self-confidence levels have risen dramatically over the last 50 years, so too have narcissism, entitlement, and unrealistic expectations. In some cases, efforts to protect or inflate children’s self-esteem have resulted in shielding them from failure, which paradoxically may limit their ability to build genuine confidence through experience.

This trend has led some to suggest that self-confidence, while vital, must be balanced and grounded in reality. Overconfidence, like low self-esteem, can be harmful—leading to poor decision-making, strained relationships, and disappointment when expectations go unmet.

Self-confidence is a powerful psychological trait that touches nearly every aspect of our lives. From promoting emotional well-being and academic achievement to strengthening resilience and enriching social relationships, the benefits of high self-confidence are extensive and well-documented (Mann et al., 2004; Atherton et al., 2016; Stankov & Lee, 2014). Yet, like any strength, it must be developed with care, authenticity, and balance. True self-confidence is not about arrogance or invincibility—it is about trusting yourself while remaining open to growth and learning. As Emerson wisely noted, “Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.” When grounded in self-awareness and nurtured through experience, self-confidence becomes more than a belief—it becomes a quiet force that helps us live with purpose, joy, and resilience.

Too Much of a Good Thing (The Consequences of Self-Esteem Education):

Over the past 25 years, Western society has embraced self-esteem as a critical pillar of psychological well-being and success. From schools to parenting practices, a central belief has taken root: if children feel good about themselves, they will thrive. This notion gave rise to the so-called self-esteem era of education, where children were routinely told they were “special,” encouraged to focus only on their strengths, and often praised for even the smallest accomplishments.

While this movement was well-intentioned, aiming to build resilient and confident individuals, recent research calls into question whether overemphasis on self-esteem may have gone too far. Scholars are now exploring whether excessive or misplaced praise is truly helping children—or if it’s actually undermining the very strengths it was meant to cultivate.

The Pitfalls of Inflated Praise and Shielded Growth: According to Carol Dweck (2007), excessive self-esteem education may have unintended negative consequences, particularly when it rewards children regardless of actual effort or achievement. When children are constantly told they are great—without corresponding expectations or challenge—it can result in:

- Low motivation, as effort becomes unnecessary for praise.

- Reduced goal-directed behavior, since children may avoid difficult tasks that challenge their inflated self-image.

- Fragile confidence, which falters easily in the face of failure or constructive feedback.

Dweck’s research highlights the dangers of focusing solely on boosting self-confidence without encouraging growth mindsets, resilience, or the capacity to learn from setbacks. Instead of building competence, this approach may lead to entitlement and a fear of failure—qualities that are ill-equipped to support success in real-world situations.

Is Self-Esteem the Problem? Or How We Cultivate It? Faced with these findings, some may wonder: Should we stop trying to boost self-confidence altogether? Psychologist Roy Baumeister and colleagues offer a more nuanced perspective. In their review, Baumeister et al. (2003) argue that self-esteem is not inherently harmful—it simply needs to be nurtured in the right way and in the right context.

Rather than abandoning self-esteem education, they recommend a measured and strategic approach. Specifically, they suggest:

- Praising effort and desirable behavior, not just outcomes or traits.

- Providing positive reinforcement only when it is earned through effort, kindness, responsibility, or creativity.

- Encouraging children to associate self-worth with meaningful action, not empty affirmation.

This more balanced method allows children to develop a realistic and healthy self-concept. They still receive emotional support and encouragement, but they also learn that success requires effort, persistence, and responsibility.

Letting Children Fail (Building Resilience Through Experience): In addition to encouraging earned praise, Steve Baskin (2011) offers another important insight: Let children fail. In the current cultural climate, many parents work hard to shield their children from pain, disappointment, or struggle. While this instinct may stem from love, it can inadvertently deprive children of critical growth experiences.

Baskin points out that failure is not only inevitable—it is essential. When children are allowed to face challenges, navigate setbacks, and manage emotional pain, they build:

- Resilience, or the ability to recover from adversity.

- Coping skills, which prepare them to handle the complexities of adult life.

- Confidence grounded in experience, not just compliments.

By allowing children to learn through trial and error, parents and educators can help them develop authentic self-esteem—based on real-world problem-solving, not a protected illusion of perfection.

Striking the Right Balance (Feeling Good and Doing Good): The key lesson from this body of research is not to abandon self-confidence education, but to redefine how we cultivate it. Rather than inflating egos with unearned praise, adults should help young people:

- Understand the value of effort, failure, and perseverance.

- Celebrate progress and character more than performance.

- Develop a realistic self-view that aligns with growth, accountability, and resilience.

Ultimately, helping children “feel their best” should not come at the cost of helping them “be their best.” Encouraging self-esteem must go hand-in-hand with guiding children toward meaningful achievement and emotional maturity. When praise is earned, honest, and tied to values like effort, kindness, and responsibility, it becomes a powerful tool for lifelong confidence.

As Baskin (2011) and Baumeister et al. (2003) agree, authentic self-esteem arises from facing challenges, not avoiding them. Letting children fall, struggle, and rise again may be one of the most empowering gifts we can give—and one that prepares them for success in the world far beyond the classroom.

The Benefits of Fear (Practicing Courage and Building Confidence):

Fear is a deeply rooted survival mechanism that has evolved to protect us from physical harm. Historically, it served a clear purpose: to keep us alive by alerting us to the presence of immediate danger—like a wild animal in the woods. But in today’s world, where physical safety is largely ensured by modern housing, vehicles, laws, and protective parenting, the function of fear has shifted. Instead of protecting us from predators, fear now responds to psychological threats—the fear of failure, rejection, embarrassment, or emotional pain.

This shift in how fear manifests has profound implications for how we grow, act, and build confidence in modern life.

Fear in the Modern Mind: Even though the threats we face today are not as life-threatening as they once were, fear still activates the same biological responses. Our bodies and minds react to criticism or public speaking the same way they might have once reacted to hearing a predator nearby. But unlike physical dangers, these emotional fears often stem from past experiences—moments when we were hurt, rejected, or embarrassed. And these experiences don’t just fade away; instead, they linger quietly in our subconscious, running in the background like open apps on a smartphone, consuming mental energy and bandwidth.

This “mental clutter” can exhaust us without us even realizing it. It clouds our thinking, increases our stress, and restricts our willingness to try new things. We retreat to our comfort zones, where everything feels safe and familiar, but where we are also protected from challenge, growth, and risk.

The Hidden Cost of Staying Comfortable: Remaining in a comfort zone for too long may feel secure, but it often comes at the cost of personal growth and confidence. When we avoid situations that challenge us—whether it’s trying something new, speaking up, or taking risks—we rob ourselves of the opportunity to learn, fail, adapt, and ultimately succeed. And the less we engage with uncomfortable experiences, the more fearful we become of them. The “what ifs” grow louder, and imagined outcomes become barriers to action.

Confidence is something that tends to thrive in familiar environments—where we know what to expect and how to perform. But in the face of uncertainty, when we don’t yet have confidence, something else must step in: courage.

Courage vs. Confidence (Why We Need Both): Courage and confidence are often seen as interchangeable, but they serve different purposes. Confidence arises from experience—it’s the self-assurance we feel when we know we can handle a task. Courage, on the other hand, is what carries us into the unknown, despite fear and uncertainty. It is the willingness to act before we feel ready, to try even when we’re unsure of the outcome.

Courage is arguably the more noble of the two because it requires more inner strength. Anyone can act confidently when they’re familiar with what they’re doing, but it takes real bravery to move forward without guarantees. And it’s precisely this practice of courage that leads to growth. The more we face our fears courageously, the more experience we gain—and that experience gradually turns into true, lasting confidence.

Reframing Fear as a Guidepost: Rather than viewing fear as an enemy, we can learn to see it as a signpost—a signal that points us toward something important. Fear often arises where there is potential for growth. By leaning into it, we can begin to sort through the limiting beliefs, painful memories, or insecurities that no longer serve us, much like decluttering an overstuffed closet. It’s not always comfortable, but it’s incredibly freeing.

Once we begin clearing out these “mental closets,” we find renewed energy and emotional space for new opportunities, experiences, and ways of thinking. Fear can become a transformative force, one that doesn’t hold us back but propels us forward.

Fear, Practice, and the Path to Confidence: Still, it’s important to recognize that overcoming fear and building confidence isn’t something that happens overnight. As the text points out, we humans are contradictory creatures—we often expect fear to vanish quickly, yet we accept that mastering a musical instrument, learning a new language, or developing a skill takes consistent practice.

Building confidence is no different. It’s a process of repeated exposure, effort, failure, and reflection. The first time you do something new, it will likely feel scary. The tenth time may feel slightly less so. Over time, courageous action leads to competence, and competence builds confidence.

To put it simply: “To build confidence, you have to practice confidence.”

This means showing up, trying again, and pushing just slightly beyond your comfort zone—not to eliminate fear, but to reshape your relationship with it. Every step you take in the presence of fear, no matter how small, strengthens your courage and makes confidence just a little more accessible the next time around.

Fear is not something we need to eliminate. In fact, it’s something we can thank—for warning us, for guiding us, and for challenging us to grow. True self-confidence isn’t born from the absence of fear, but from the ability to act in spite of it. By practicing courage, stepping into discomfort, and reframing fear as a tool rather than a threat, we gradually shape a more resilient, confident, and capable version of ourselves. Instead of asking, “How can I avoid fear?” the better question might be, “What is fear trying to show me?” Because often, just on the other side of fear, lies everything we’re capable of becoming.

9 Lessons for Practicing Self-Confidence:

Self-confidence is often considered the backbone of personal growth and wellbeing. But as renowned psychologist Martin Seligman reminds us, “a positive self-image by itself does not produce anything.” Instead, he argues that true and lasting self-assurance comes from what we do—from taking positive, productive action in our lives (Seligman, 1996). In other words, it’s not just about thinking highly of ourselves—it’s about earning that belief through meaningful engagement and effort.

This isn’t to say that feeling secure in oneself isn’t important. In fact, high levels of self-confidence—or self-efficacy—have been strongly linked to better mental and physical health outcomes (Pajares, 1996). But for many people, especially in times of stress or transition, cultivating self-confidence can feel like an uphill climb. We may wrestle with self-doubt, negative inner dialogue, or fear of failure. The good news? With conscious practice, reflection, and a willingness to change perspective, we can nurture a resilient and grounded belief in ourselves.

Seligman puts it beautifully: “Wellbeing cannot just exist in our own head. It is a combination of actually having meaning, good relationships, and accomplishment.”

Below are nine practical lessons for building and sustaining self-confidence—tools that help us not just feel good about ourselves, but also live in a way that reinforces that feeling through experience.

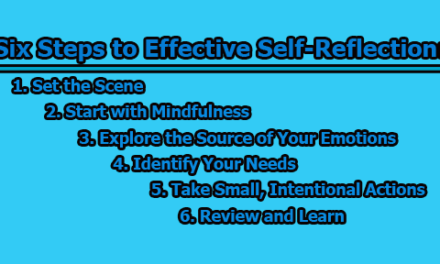

- Stand or Sit in a Posture of Confidence: Your body speaks before you do. According to Harvard psychologist Amy Cuddy and her colleagues, body posture doesn’t just reflect how you feel—it can actually shape how you feel. Certain “power poses” (such as standing tall with hands on hips or sitting upright with shoulders back) can lead to measurable shifts in hormone levels that make you feel more confident and in control.

So, try this: next time you’re facing a challenge, check your posture. Feel your feet grounded firmly, keep your chest open, and allow your body to relax into a dignified presence. Think regal. Whether you’re walking into a job interview, giving a presentation, or entering a social setting—your posture can be your silent ally.

- Practice Presence: Mindfulness is a proven technique for improving emotional resilience, reducing stress, and enhancing wellbeing. It also plays a powerful role in building confidence. Practicing presence helps you tune into the moment rather than ruminating on past failures or future anxieties.

Start simple:

- Take a few deep breaths.

- Notice your body sensations—your feet on the ground, the movement of your breath.

- Expand your awareness to include sounds, sights, smells, and the energy in your surroundings.

With practice, this kind of mindful attention cultivates a calm inner state and a steady sense of self—both key foundations for confidence.

- Build Your Capacity for Energy: You’ve probably heard of “fight or flight,” but a little stress—what psychologists call “eustress”—can actually be helpful. That fluttery nervous energy before a big performance? Try reframing it as excitement rather than fear.

Confidence is not always about feeling calm—it’s often about being able to channel your energy productively. So, instead of shrinking from the sensation of nervousness, welcome it as your body’s signal that you’re stepping up. Use that spark to expand your presence and focus.

- Exercise Regularly: Physical activity isn’t just good for your body—it’s essential for your mind. Regular exercise releases endorphins, which are feel-good chemicals in the brain that improve mood and outlook. It also helps regulate sleep, improve energy, and sharpen focus—all of which feed into a more confident sense of self.

When you move your body regularly, you’re not only improving your health—you’re proving to yourself that you are capable of consistent effort and care.

- Visualize (Imagine Confidence): Close your eyes, take a deep breath, and picture yourself doing the thing you fear. Whether it’s speaking in public, approaching a new opportunity, or handling conflict—imagine yourself succeeding. See it, feel it, and stay grounded in the sense of calm control as you visualize.

Visualization helps build neural pathways in the brain that mirror actual experiences. By rehearsing success mentally, you’re preparing yourself to feel more confident in real life.

- Give Yourself Permission to Be in the Process, Take Risks, and Make Mistakes: It’s easy to assume that others have it all together while we flounder. But the truth is, everyone struggles—especially when they’re trying something new. The difference between confident people and others isn’t perfection—it’s persistence.

Allow yourself to be a beginner. Give yourself permission to fail, to learn, and to improve over time. Confidence isn’t built in a vacuum—it grows in the midst of uncertainty, trial, and error.

Stepping outside your comfort zone is risky, yes—but every successful moment beyond that boundary strengthens your self-belief.

- Clarify Your Goals: Clarity fuels confidence. When you know what you’re working toward—and why—it’s easier to stay motivated and trust yourself along the way.

Seligman’s PERMA model of wellbeing includes Accomplishment as a key pillar. Progress on meaningful goals contributes greatly to our sense of purpose and competence.

Use the S.M.A.R.T. goals system to make your objectives clear: (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-bound)

Set big-picture goals based on your values, then break them down into achievable steps. Even small wins create positive momentum.

As Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi said, “Happiness does not simply happen to us. It’s something that we make happen and it comes from doing our best.”

- Speak Well to Yourself: What you say to yourself matters—a lot. The inner voice that runs through your head all day can either lift you up or tear you down. Learn to become your own encourager.

“Approve of yourself; be the one that says the words of encouragement you long to hear.”

Instead of waiting for validation from others, offer it to yourself. Practice self-talk that is kind, honest, and uplifting. When you stumble, speak to yourself as you would to a dear friend.

- Ask for Help and Offer Help to Others: Confidence doesn’t mean doing everything alone. In fact, some of the most secure people are those who know when to ask for support.

Research by Baumeister and Leary (1995) emphasizes that belonging and connection are essential to wellbeing. When we contribute to others and allow others to support us, we strengthen both our self-worth and our social bonds.

Stephen Post (2008) found that acts of altruism—whether volunteering, mentoring, or simply helping a friend—are deeply linked to happiness. Giving boosts confidence by reminding us of our value in the world.

And don’t underestimate others’ willingness to help. Stanford professor Frank Flynn (2008) showed that people often underestimate how ready others are to lend a hand. So reach out—you might be surprised.

As Martin Seligman put it, “Doing a kindness produces the single most reliable increase in momentary wellbeing than any other exercise we have tested.”

Building self-confidence is not a one-time achievement—it’s a practice, a process of showing up for yourself again and again. These nine lessons are starting points, not finish lines. With patience and persistence, you can cultivate a confidence that’s not just surface-level, but grounded in experience, values, and authentic self-worth.

In conclusion, building and maintaining self-confidence is a dynamic, ongoing process that requires attention, effort, and thoughtful engagement—both from individuals and those who support them. As Martin Seligman (1996) rightly reminds us, “a positive self-image by itself does not produce anything”; rather, confidence is developed through meaningful actions, constructive experiences, and the freedom to learn from failure.

For parents, teachers, and caregivers, the goal should not be to shield children from every difficulty but to provide them with safe and supportive environments in which they can grow from challenges. Praising effort, rewarding socially positive behavior (Baumeister et al., 2003), and even allowing for failure (Baskin, 2011) are crucial components in fostering genuine confidence and resilience. When children (and adults) are encouraged to face their fears, take thoughtful risks, and trust in their own ability to learn and adapt, they build not only self-confidence but a stronger sense of self-efficacy and purpose.

Ultimately, true confidence is not a fixed trait—it fluctuates over time and must be practiced like any other skill. By understanding its foundations, embracing courage, and nurturing environments that encourage realistic growth, we can cultivate a more authentic and sustainable self-confidence in ourselves and those around us.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Can self-confidence be taught, or is it something people are born with?

Self-confidence is not an inborn trait; it’s a skill that can be developed over time. While some individuals may naturally exhibit more confidence due to temperament or early experiences, most people build self-confidence through repeated experiences of effort, learning, failure, and eventual success (Seligman, 1996).

What’s the difference between self-esteem and self-confidence?

Self-esteem refers to how much you value yourself, while self-confidence is how much you believe in your ability to succeed in specific situations. Healthy self-esteem provides a solid foundation, but true self-confidence is built through action and mastery of challenges (Pajares, 1996).

Is it harmful to praise children too much?

Yes, excessive or empty praise can be counterproductive. Praising children without linking it to effort or meaningful behavior can promote entitlement or unrealistic self-perception. According to Baumeister et al. (2003), praise should be measured and directed toward socially desirable or goal-oriented behaviors.

How does failure help build confidence?

Failure provides opportunities for learning and growth. Allowing children—or ourselves—to experience failure in safe environments builds resilience, coping skills, and ultimately confidence. Steve Baskin (2011) suggests that shielding children from failure can prevent emotional growth and self-efficacy.

Can fear actually improve confidence?

Yes. Fear can serve as a guidepost to areas where growth is possible. Embracing fear and stepping outside of our comfort zones strengthens courage, which leads to increased confidence over time. Confidence often follows courage—not the other way around.

What are some daily habits that can boost self-confidence?

- Practicing power postures (Amy Cuddy’s research)

- Mindfulness and presence exercises

- Regular physical exercise

- Speaking kindly to yourself

- Setting and achieving SMART goals

- Visualizing success

- Asking for help and contributing to others

Why is courage considered more powerful than confidence?

Courage allows individuals to take action even when they don’t feel confident. Confidence may exist within the familiar, but courage shines in the unknown. It’s through repeated courageous actions that lasting confidence is formed.

How can educators foster genuine confidence in students?

Educators can:

- Encourage risk-taking and normalize failure as part of learning

- Praise effort and strategy over intelligence or results

- Offer constructive feedback

- Set appropriately challenging tasks

- Model vulnerability and resilience

Is asking for help a sign of weakness or strength?

It’s a sign of strength. Research by Flynn (2008) indicates that people tend to underestimate how willing others are to help. Asking for support builds community, and offering help to others also boosts confidence and wellbeing (Post, 2008).

Can self-confidence affect physical health?

Yes. Studies have shown that higher self-confidence is associated with better stress management, improved immune function, and more positive health behaviors. Confidence helps people take proactive steps in caring for their physical and mental health (Pajares, 1996).

References:

- Atherton, S., Antley, A., Evans, N., Cernis, E., Lister, R., Dunn, G., Slater, M., & Freeman, D. (2016). Self-confidence and paranoia: An experimental study using an immersive virtual reality social situation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 44, 56-64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465814000496

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Baskin, S. (December 31, 2011). The gift of failure: Letting our children struggle is a difficult gift to give. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/za

- Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1529-1006.01431

- Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2002). Self-confidence and personal motivation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 871-915. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355302760193913

- Branden, N. (1969). The psychology of self-esteem. Los Angeles, CA: Nash Publishing.

- Brinkman, D. J., Tichelaar, J., van Agtmael, M. A., de Vries, T. P. G. M., & Richir, M. C. (2015). Self-reported confidence in prescribing skills correlates poorly with assessed competence in fourth-year medical students. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 55, 825-830. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.474

- Burton, N. (2015). “Self-Confidence Versus Self-Esteem.” Psychology Today.

- Cherry, K. (2016, August 31). How do psychologists define self-esteem?

- Clark, N. M., & Gakuru, O. N. (2014). The effect on health and self-confidence of participation in collaborative learning activities. Health Education & Behavior, 41, 476-484. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198114549157

- Craig, C. (2006). Seligman’s Critique of Self-Esteem.

- Druckman, D., & Bjork, R. A. (Eds.). (1994). Learning, remembering, believing: Enhancing human performance. National Academy Press: Washington, D.C., US.

- Dweck, C. S. (1999). Caution-Praise Can be Dangerous.

- Edberg, H. (2007). Top 24 Tips for Making Your Self Confidence Soar.

- Fodor, M. (2009). Self-Expansion. Budapest: Psychology 2.0 Books.

- Fonvielle, D., & Greater, A. (2011). What is self-confidence about? Retrieved from http://www.alwaysgreater.com/achievements/what-does-self-confidence-mean-to-you

- Forsyth, D. R., Lawrence, N. K., Burnette, J. L., & Baumeister, R. R. (2007). Attempting to improve the academic performance of struggling college students by bolstering their self-esteem: An intervention that backfired. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 447-459. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2007.26.4.447

- Gloppen, K. M., David-Ferdon, C., & Bates, J. (2010). Confidence as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46, S42-S58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.216

- Greenberg, J., & Arndt, J. (2011). Terror management theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.) Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Collection: Volumes 1 & 2, 398-415.

- Greater, Always. (n.d.) Why Is Confidence Important In Life? Retrieved from https://alwaysgreater.com/why-is-self-confidence-important-benefits-of-self-confidence/

- Kremer, W. (January 4, 2013). Does confidence really breed success? BBC World Service. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news

- Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 518-530. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.518

- Lenney, E. (1977). Women’s self-confidence in achievement settings. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.1.1

- Mann, M., Hosman, C. M. H., Schaalma, H. P., & de Vries, N. K. (2004). Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Education Research, 19, 357-372. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyg041

- Manson, M. (2015). The Confidence Conundrum. Retrieved from https://alwaysgreater.com/why-is-self-confidence-important-benefits-of-self-confidence/

- Mobius, M. M., Niederle, M., Niehaus, P., & Rosenblat, T. S. (2011). Managing self-confidence: Theory and experimental evidence. National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper.

- MTD Training. (2010). Personal Confidence and Motivation. London: Training and Ventus Publishing.

- Oney, E., & Oksuzoglu-Guven, G. (2015). Confidence: A critical review of the literature and an alternative perspective for general and specific self-confidence. Psychological Reports, 116, 149-163. https://doi.org/10.2466/07.PR0.116k14w0

- Rigoglioso, M. (2008) Frank Flynn: If You Want Something, Ask For It. Retrieved from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/francis-flynn-if-you-want-something-ask-it.

- Self-confidence [Def. 1 and 2]. (n.d.). Psychology Dictionary. Retrieved from http://psychologydictionary.org/self-confidence/

- Skenderis, V. M. (2015). Implementing a team approach to improve positive behavioral changes for 9th graders: An action research study. Capella University, ProQuest Information & Learning. UMI number 3705434

- Stankov, L. (2013). Noncognitive predictors of intelligence and academic achievement: An important role of confidence. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 727-732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.07.006

- Stankov, L. & Lee, J. (2014). Quest for the best non-cognitive predictor of academic achievement. Educational Psychology, 34, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.858908

- Weisul, K. (n.d.). 2 Quick Exercises That Will Boost Your Confidence. Retrieved from https://www.inc.com/kimberly-weisul/two-short-simple-exercises-that-will-boost-your-confidence.html

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College