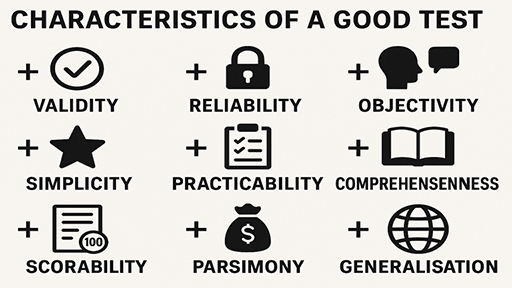

Characteristics of a Good Test:

Educational assessment is an integral component of the teaching-learning process, serving as a means to measure students’ knowledge, skills, and competencies. A well-constructed test not only evaluates learning outcomes but also guides future instruction, motivates learners, and provides accountability to stakeholders. However, for a test to serve its purpose effectively, it must possess certain essential characteristics. These characteristics ensure that the test produces consistent, fair, and meaningful results that truly reflect the abilities of the learners. This article discusses nine key characteristics of a good test: validity, reliability, objectivity, simplicity, practicability, comprehensiveness, scorability, parsimony, and generalisation.

1. Validity: Validity is universally regarded as the cornerstone of any good test because it determines whether the test actually measures what it is designed to measure (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Validity is not a single concept but a family of related ideas, often grouped into three main types:

- Content Validity: This refers to the extent to which a test adequately samples the domain of content it aims to assess. For example, a final exam for a high school algebra course should include questions covering all key units taught, not just a few chapters. Teachers often use curriculum blueprints or test specifications to ensure content validity (Nitko & Brookhart, 2014).

- Construct Validity: This deals with whether the test truly measures the theoretical construct it claims to measure. For instance, a test designed to assess “critical thinking” should include tasks that require analysis, evaluation, and synthesis — not just recall of facts (Mertler, 2016).

- Criterion-related Validity: This involves comparing test scores with an external criterion. For example, SAT scores are expected to correlate strongly with students’ first-year college GPA. If this correlation is high, the SAT has strong predictive validity for college performance (Popham, 2017).

Validity is an ongoing process — test developers must continuously gather evidence to support their claims about what the test measures and how its results are interpreted. As Creswell and Creswell (2018) emphasize, no test is perfectly valid, but rigorous test design and evaluation can maximize its validity.

2. Reliability: Reliability is about the consistency, stability, and dependability of test scores (Mertler, 2016). A test that yields wildly different results under the same conditions is unreliable and therefore of little practical use, no matter how valid it might be in theory. There are several forms of reliability:

- Test-Retest Reliability: This checks if a test yields similar results when administered to the same group at two different times. For instance, a reading comprehension test given to students twice within a week should show similar scores if no real learning has occurred in between (Nitko & Brookhart, 2014).

- Inter-Rater Reliability: This measures the degree of agreement among different scorers. For subjective tasks like essay writing or project work, clear rubrics and training help ensure consistency between scorers (Popham, 2017).

- Internal Consistency: This refers to how well the items on a test measure the same construct. For example, all questions on a math test should assess math ability — not unrelated skills like grammar. Statistical methods such as Cronbach’s alpha help quantify internal consistency (Mertler, 2016).

Reliability is a prerequisite for validity: if scores are inconsistent, they cannot be valid indicators of student ability (Brown, 2004).

3. Objectivity: Objectivity means that scoring and interpretation are free from personal bias or subjectivity (Popham, 2017). In a good test, two examiners marking the same answer should award the same score. This is especially important in large-scale or high-stakes testing where fairness and transparency are critical. Ways to enhance objectivity include:

- Using Objective Item Formats: Multiple-choice, true-false, and matching questions have fixed correct answers, which reduces scorer bias (Nitko & Brookhart, 2014). For example, in standardized tests like TOEFL, machine scoring ensures objectivity.

- Clear Rubrics for Subjective Items: When subjective judgment is unavoidable, as in essays or presentations, scoring rubrics with well-defined criteria help ensure that marks are awarded consistently (Mertler, 2016). Training scorers to use these rubrics reliably is essential.

- Blind Scoring: In some contexts, student names are hidden from scorers to avoid bias based on prior knowledge of the student’s ability or behavior.

Ultimately, a highly objective test increases the trustworthiness of test results, thereby strengthening the fairness of educational decisions made using those results.

4. Simplicity: Simplicity means a test should be clear, straightforward, and easy to understand for both the test-takers and the examiners (Brown, 2004). Complex wording, confusing instructions, or unnecessarily complicated formats can create barriers that prevent students from showing what they really know or can do. Key aspects of simplicity include:

- Clear Language: The wording of questions and instructions must match the learners’ language proficiency level. For example, in a Grade 6 science test, overly technical jargon should be avoided unless it is explicitly taught content (Nitko & Brookhart, 2014).

- Unambiguous Questions: Test items should have only one correct answer unless the format specifically allows for multiple answers. Vague or trick questions reduce fairness and can frustrate learners (Popham, 2017).

- Simple Layout and Format: A clear structure, consistent numbering, and logical ordering of sections help students navigate the test easily. Confusing layouts can waste time and cause anxiety.

Example: In large-scale language tests like the IELTS or TOEFL, test designers rigorously review questions to ensure clarity and simplicity. The goal is for the test-taker’s score to reflect language ability — not test-taking skill or the ability to decode complex instructions (Brown, 2004).

5. Practicability: Practicability (or feasibility) refers to how realistic and manageable it is to prepare, administer, and score the test within the constraints of available resources, time, and context (Nitko & Brookhart, 2014). Even the most valid and reliable test is of little use if it is too expensive or complicated to implement. Practicability includes:

- Time Constraints: A good test should be completable within the available time. For example, a one-hour classroom period limits how many questions can reasonably be included (Mertler, 2016).

- Resource Availability: The test should not require resources that are impractical to provide. For example, a speaking test that needs expensive recording equipment may not be practical for under-resourced schools.

- Ease of Administration: Tests should be easy to administer to large groups when necessary. Clear instructions, manageable logistics, and minimal special arrangements make this possible.

Example: Standardized multiple-choice tests are popular partly because they are practical to administer and score for large numbers of students. In contrast, portfolio assessments may be ideal for demonstrating complex skills but can be impractical for large-scale, time-bound testing contexts (Popham, 2017).

6. Comprehensiveness: Comprehensiveness means that a test adequately covers the entire range of intended learning outcomes, ensuring a balanced and representative sampling of the subject matter (Mertler, 2016). A test that focuses too narrowly on a few topics risks giving a distorted picture of a learner’s overall knowledge or skills. Key points for ensuring comprehensiveness:

- Representative Sampling: The test should include questions from all major units or skill areas taught, weighted according to their importance and emphasis in the curriculum (Nitko & Brookhart, 2014).

- Balance of Difficulty Levels: A comprehensive test includes items that range from simple recall to higher-order thinking skills like analysis, synthesis, or application (Bloom’s Taxonomy).

- Variety of Question Types: Using multiple formats — such as multiple-choice, short-answer, and problem-solving items — helps assess different cognitive skills comprehensively.

Example: In national curriculum exams, test blueprints or test specifications guide item writers to ensure that all syllabus areas are proportionally represented. For instance, a balanced history test will include questions on political, social, and economic aspects rather than focusing only on battles and dates (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

7. Scorability: Scorability refers to how easily, accurately, and consistently a test can be scored (Popham, 2017). A good test should have scoring procedures that are clear and straightforward so that examiners can mark responses efficiently and students can trust that scores are fair. Key aspects of scorability include:

- Clear Answer Keys: For objective items like multiple-choice or true-false questions, there should be an unambiguous, definitive answer key. This makes scoring quick and ensures consistency (Nitko & Brookhart, 2014).

- Scoring Rubrics for Subjective Items: When tasks require subjective judgment (e.g., essays, open-ended responses, or projects), detailed rubrics help ensure fairness. Well-designed rubrics describe performance levels, criteria, and descriptors so that different scorers reach similar conclusions (Mertler, 2016).

- Minimizing Ambiguity: Test items should avoid vague wording that could lead to multiple reasonable answers, which complicates scoring.

Example: Standardized tests such as the TOEFL and IELTS include both machine-scored multiple-choice sections and human-scored writing and speaking sections. The writing and speaking tasks are marked by multiple raters using detailed scoring rubrics to maintain consistency and minimize scorer bias (Brown, 2004).

8. Parsimony: Parsimony means that a test should be economical in terms of time, effort, and resources while still fulfilling its purpose (Brown, 2004). A good test gathers the maximum useful information with the minimum number of items, instructions, and administrative steps. Key aspects of parsimony include:

- No Unnecessary Items: Avoid redundant questions that test the same point repeatedly. Each item should contribute uniquely to the overall goal of the test (Popham, 2017).

- Balanced Length: A test that is too long can exhaust students and examiners alike, while a test that is too short might not yield enough data for valid judgments. Finding the right length is part of parsimony.

- Efficient Scoring and Administration: A parsimonious test reduces administrative burden by being easy to distribute, collect, and score within time and logistical constraints (Nitko & Brookhart, 2014).

Example: In classroom settings, quizzes and formative assessments should be designed to quickly gauge student understanding without using up entire lessons unnecessarily. For instance, a well-designed 10-item quiz may give better feedback than an unstructured 50-item test (Mertler, 2016).

9. Generalisation: Generalisation means that the test results should be applicable to similar contexts, situations, or populations beyond the specific test setting (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). If a test is too narrowly focused or heavily dependent on local factors, its results may not provide valid insights when applied more broadly. Key aspects of generalisation include:

- Representative Content: When a test’s tasks and content reflect real-world applications, its results are more likely to generalize to other contexts. For example, performance-based tasks that simulate authentic scenarios help ensure generalisability.

- Standardized Administration: Administering the test under consistent conditions makes it easier to compare results across groups or settings (Nitko & Brookhart, 2014).

- Reliable and Valid Items: A test with strong validity and reliability naturally supports generalisation, since scores are more likely to reflect the true abilities of test-takers and not irrelevant factors (Popham, 2017).

Example: Standardized achievement tests in schools are designed to produce scores that help compare student performance across schools, districts, or even countries (e.g., the PISA tests). The results must generalize beyond a single classroom or teacher (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

In conclusion, a good test is one that upholds the qualities of validity, reliability, objectivity, simplicity, practicability, comprehensiveness, scorability, parsimony, and generalisation. These characteristics ensure that the test fulfills its role as an accurate, fair, and effective tool for assessing learning outcomes. Educators and test developers must keep these principles in mind to create assessments that truly support teaching and learning in meaningful ways.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Why is validity considered the most important feature of a test?

Validity is crucial because it determines whether the test truly measures what it is intended to measure. For example, if a test is designed to assess problem-solving in mathematics but only contains questions that check basic arithmetic, it does not truly measure problem-solving skills. A valid test ensures that teachers, students, and even parents can trust that the test results accurately reflect students’ abilities and knowledge in the specific area the test targets. When validity is high, decisions about student promotion, grades, or interventions are more likely to be fair and appropriate.

How can teachers increase the reliability of their tests?

Reliability can be strengthened by designing clear, unambiguous questions that different students interpret the same way. Teachers can also ensure consistent test administration: for example, giving all students the same time limit, instructions, and environment. Using a range of question types — such as multiple-choice, short answer, and essays — and checking that they align well with the learning objectives also helps. When subjective items like essays are included, using detailed scoring rubrics and, if possible, having another teacher cross-check a sample of marked papers helps maintain reliability.

What is the difference between reliability and objectivity?

Reliability is about overall consistency — it means a test gives stable results over time, with different scorers, or when used with different groups under similar conditions. Objectivity is narrower: it means the scoring process is free from personal bias. For example, if two teachers score the same essay, their marks should be the same if the test is objective. Objectivity helps build reliability, but a test can be reliable yet still biased if the scoring method depends too much on individual judgment. To maximize both, objective-type questions like multiple-choice and clear rubrics for subjective tasks are widely used.

Why is simplicity important if the test is already valid and reliable?

Simplicity ensures that test-takers clearly understand what is expected of them. Even a valid and reliable test will fail if students cannot comprehend the instructions or questions. For instance, a complex, jargon-filled question might confuse students who actually know the content but misunderstand what the question asks. Simplicity also reduces test anxiety and helps students focus on showing what they know, rather than wasting time trying to interpret confusing wording or unclear layouts.

How does practicability affect classroom and large-scale tests?

Practicability makes sure a test can realistically be prepared, administered, and marked within the time, budget, and resources available. For example, an oral interview may be an excellent way to test speaking skills but is often impractical for a teacher with 60 students and only one class period. In large-scale exams, practicability includes considerations like how many test papers can be printed, how scores will be processed, and whether teachers have enough time to mark them before reports are due. Practical tests help schools run efficiently and reduce stress for teachers and learners.

What does comprehensiveness look like in practice?

A comprehensive test covers all the important content areas and skills taught during a course or unit. For example, if students learn about reading, writing, and speaking in an English course, the test should include tasks that check each of these — not just grammar rules. Comprehensive tests help ensure that students are prepared for the real world, where they need a combination of skills. They also give a more accurate picture of a student’s overall ability, rather than just their strength in one topic.

Why is scorability so important for teachers and students?

Scorability makes it easier for teachers to mark tests quickly and accurately. When scoring rules are clear, teachers spend less time deciding how many marks to award for each answer. For students, clear scoring means they can understand where they gained or lost marks, which helps them learn from mistakes. For large exams, scorability ensures that results can be delivered on time — which is vital when results affect graduation, college entry, or scholarship decisions.

What does parsimony mean and why does it matter?

Parsimony means the test does not waste time or effort. Each question should serve a clear purpose and add unique value. Overly long or repetitive tests can tire students, lower motivation, and waste class time that could be spent on teaching or feedback. Parsimony encourages teachers to focus on writing strong, well-targeted questions that gather maximum information with minimum burden.

How does generalisation make a test more meaningful?

Generalisation means that the test results give teachers reliable information that can be applied beyond that specific test. For example, if a student does well on a science exam that includes real-world problem-solving tasks, the teacher can be more confident that the student will do well in future science lessons or similar situations. This is especially important for high-stakes tests, where results often influence school placement, scholarships, or job opportunities.

Is it possible to create a test that perfectly meets all these qualities?

In reality, no test is perfect in every aspect. There are often trade-offs — for example, adding more questions might make a test more comprehensive but less practical to administer. However, a good test strikes a balance by being valid, reliable, objective, simple, practical, comprehensive, scorable, economical (parsimonious), and meaningful beyond the classroom. Teachers and test designers aim to balance these characteristics to create fair, effective, and manageable assessments.

References:

- Brown, H. D. (2004). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices. Pearson Education.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Mertler, C. A. (2016). Classroom assessment: A practical guide for educators (6th ed.). Routledge.

- Nitko, A. J., & Brookhart, S. M. (2014). Educational assessment of students (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Popham, W. J. (2017). Classroom assessment: What teachers need to know (8th ed.). Pearson.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College