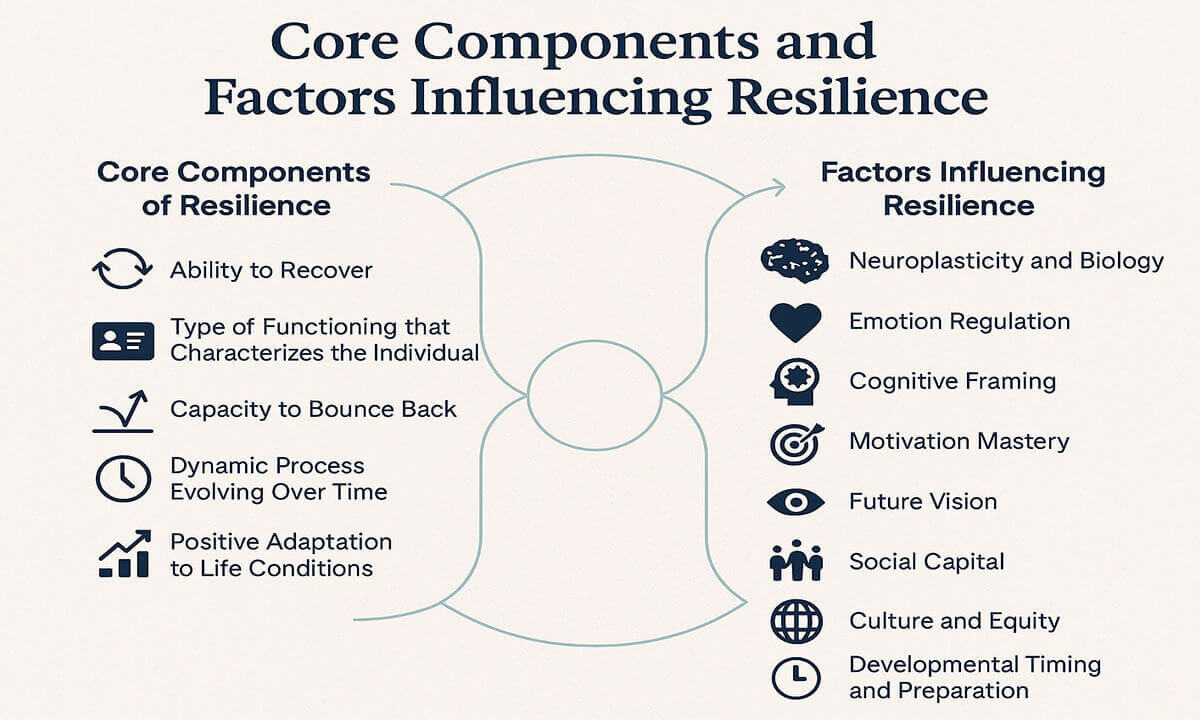

Core Components and Factors Influencing Resilience:

Resilience has emerged as one of the most important psychological and social concepts for understanding how individuals respond to stress, trauma, and life’s inevitable challenges. It refers to the capacity to adapt successfully when faced with adversity, to recover from hardship, and to discover new strengths in the process. Rather than being a fixed trait that only some people possess, resilience is better understood as a dynamic and evolving capacity that grows through personal experience, relationships, and cultural context (Sisto et al., 2019). Over the last few decades, research in psychology, neuroscience, and social sciences has identified the central components that shape resilience as well as the conditions that influence its development. These insights reveal that resilience is not simply about “bouncing back” but is also about growth, transformation, and meaning-making in the aftermath of difficulty. To understand resilience more fully, it is necessary to look at both its internal components and the external factors that contribute to its development. In the rest of this article, we will explore the core components and factors influencing resilience.

Core Components of Resilience:

Resilience theory highlights several essential components that enable individuals to recover from hardship, adapt to change, and find meaning even in the most difficult of circumstances. These components illustrate resilience as a multifaceted and evolving process rather than a singular ability (Sisto et al., 2019).

1. Ability to Recover: At the heart of resilience lies the capacity to recover from distress and restore psychological balance. Recovery does not mean erasing painful experiences or pretending they never happened. Instead, it involves recognizing the difficulty, integrating it into one’s life narrative, and continuing to move forward without being dominated by the memory of pain. A person who has lost a loved one may still carry the grief, but over time they may also find ways to honor that memory while re-engaging with life’s responsibilities and opportunities. This form of recovery demonstrates that resilience is not about avoiding suffering but about cultivating the strength to live meaningfully despite it.

2. Type of Functioning That Characterizes the Individual: Resilience is also shaped by enduring qualities of an individual’s functioning. Certain personality traits and adaptive styles, such as optimism, perseverance, and cognitive flexibility, play a significant role in how people withstand hardship. Some individuals naturally view difficulties as challenges to be managed rather than threats that overwhelm them. These traits can be partly innate, but they are also strongly shaped by upbringing, environment, and cultural influences. For example, a supportive family and community environment may cultivate optimism and confidence, equipping an individual with the mindset needed to confront life’s difficulties.

3. Capacity to Bounce Back: Resilience involves more than simply recovering to a previous state of balance. It also includes the capacity to bounce back from setbacks and turn them into opportunities for growth. People who embody this capacity often emerge from challenges stronger than before. Instead of remaining stuck in survival mode, they use adversity as a source of learning and transformation. This process reinforces self-efficacy, as each successful adaptation builds greater confidence in one’s ability to handle future struggles. In this way, resilience is not only about survival but also about personal growth.

4. Dynamic Process Evolving Over Time: Another key component of resilience is its dynamic and evolving nature. Resilience is not a static trait that remains unchanged throughout life. It develops and shifts depending on age, life experiences, relationships, and social contexts. A child may demonstrate resilience through play and imagination when navigating family challenges, while an adult may draw on past experiences and problem-solving skills to cope with workplace stress. Over time, new challenges and environments shape resilience in different ways. This highlights the importance of viewing resilience as a process that grows and adapts rather than as a fixed quality.

5. Positive Adaptation to Life Conditions: Finally, resilience can be understood as the capacity for positive adaptation. Even when faced with ongoing stress or traumatic events, resilient individuals find ways to regulate their emotions, maintain purpose, and continue engaging with life. Positive adaptation does not mean avoiding pain or difficulty but learning to live well despite them. It often includes making meaning from challenges, such as finding purpose in helping others after personal loss. In this way, resilience ensures that individuals remain active participants in their lives, capable of navigating both stability and change.

Taken together, these components emphasize that resilience is both a recovery process and a pathway to growth. It involves healing, adapting, and transforming in ways that preserve an individual’s sense of self and purpose. As Sisto and colleagues (2019) explain, resilience represents the ability to stay connected with one’s deeper values and life goals while navigating adversity, ultimately leading to greater personal strength and insight.

Factors Influencing Resilience:

While the core components highlight what resilience looks like, it is equally important to understand the factors that influence its development. Resilience is shaped by both internal processes and external supports, ranging from biological mechanisms to cultural practices. Research consistently demonstrates that resilience is the outcome of an interaction between individual resources and environmental conditions (Lohner & Aprea, 2021; Southwick et al., 2014).

1. Neuroplasticity and Biology: The brain’s ability to adapt and rewire itself, known as neuroplasticity, plays a fundamental role in resilience. Traumatic experiences may leave lasting effects on the brain, but practices such as journaling, gratitude, and expressive writing can promote new neural pathways that support healing. Biology is not destiny. While genetic and physiological factors contribute to how individuals respond to stress, deliberate practices can reshape responses and strengthen emotional regulation. This biological foundation explains why therapeutic interventions that engage both mind and body can be effective in fostering resilience.

2. Emotion Regulation: Another critical factor is the ability to manage and regulate emotions. Resilient individuals know how to adjust their emotional responses when faced with obstacles. Rather than being consumed by anger, sadness, or fear, they find constructive ways to process these emotions and move forward. Emotion regulation skills can be cultivated through self-reflection, mindfulness, and problem-solving exercises. For example, learning to pause and reframe a stressful situation can prevent individuals from being overwhelmed and instead encourage adaptive coping.

3. Cognitive Framing: Resilience often depends on how individuals interpret adversity. Cognitive framing refers to the process of seeing hardship not as an insurmountable defeat but as an opportunity for transformation. This shift in perspective allows individuals to integrate painful experiences into their personal story with insight rather than shame. For example, survivors of trauma may choose to view their recovery journey as a source of strength, using it to inspire others or to advocate for change. By reframing adversity in this way, individuals gain a sense of meaning that supports long-term resilience.

4. Motivation Mastery: Persistence and determination are also central to resilience. People who are motivated to keep trying, even in the face of repeated setbacks, build a sense of mastery and agency. Every effort, whether successful or not, strengthens the belief that challenges can be navigated. This perseverance not only supports immediate recovery but also develops confidence for future difficulties. Motivation mastery therefore transforms adversity into a learning process that builds long-term capacity.

5. Future Vision: Resilient individuals often maintain a sense of hope and vision for the future. Believing that life can still hold meaning and that present actions can shape a better tomorrow provides direction and purpose even in the midst of hardship. This forward-looking mindset helps individuals endure immediate challenges while remaining focused on long-term goals. Hope is not simply wishful thinking but an anchor that fuels resilience by giving people reasons to continue striving.

6. Social Capital: Human connection is one of the strongest predictors of resilience. Supportive networks of family, friends, mentors, and communities provide both emotional and practical assistance. These relationships help individuals feel less isolated in their struggles and create a sense of belonging. Social capital therefore serves as a protective factor that enhances the ability to adapt and recover. Strong communities and close relationships can make the difference between despair and the courage to keep moving forward.

7. Culture and Equity: Resilience is also shaped by culture, which influences how people understand and respond to adversity. Cultural practices often provide collective ways of healing, such as rituals, storytelling, and shared values. At the same time, access to basic needs such as housing, healthcare, and safety forms the foundation for recovery. Inequities in these areas create chronic stress that cannot be overcome by individual effort alone. Addressing systemic inequalities is therefore essential for supporting resilience across populations.

8. Developmental Timing and Preparation: Finally, the stage of life in which adversity occurs influences how resilience develops. Younger individuals may have fewer coping strategies but greater capacity for growth, while older adults may draw on accumulated life experience to navigate challenges. Preparation and developmental context shape how adversity is experienced and managed. Tailoring resilience-building strategies to different life stages ensures that individuals receive the support most appropriate for their needs.

In conclusion: resilience is a multifaceted and evolving process that reflects both the internal strengths of individuals and the external supports of their environments. Its core components include the ability to recover from distress, adaptive personality functioning, the capacity to bounce back, the dynamic nature of resilience over time, and positive adaptation to life conditions. These components illustrate that resilience is not simply about survival but about growth and transformation (Sisto et al., 2019).

At the same time, resilience is influenced by a wide range of factors, including neuroplasticity, emotion regulation, cognitive framing, motivation, future vision, social connections, cultural practices, equity, and developmental timing. Each of these factors shapes how individuals confront adversity and how they find meaning and purpose in the process (Lohner & Aprea, 2021; Southwick et al., 2014).

By understanding both the core components and influencing factors, we recognize resilience as a capacity that can be nurtured and strengthened. It is not only a personal resource but also a collective responsibility, shaped by the systems and cultures in which people live. Supporting resilience therefore requires attention to both individual practices and broader social conditions. When cultivated intentionally, resilience empowers individuals and communities to face adversity not with despair, but with strength, adaptability, and hope.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Is resilience something people are born with or can it be developed?

Resilience is not an inborn trait that only a few people naturally possess. While some personality characteristics such as optimism or adaptability may make resilience easier, most of it can be learned and strengthened over time. Through consistent practices like mindfulness, journaling, therapy, and healthy relationships, resilience becomes a skill that grows at any age.

How does resilience differ from simple coping skills?

Coping skills usually address short-term stress management, such as relaxation exercises or problem-solving techniques. Resilience, on the other hand, is broader. It is the long-term capacity to adapt, recover, and even grow stronger after adversity. Coping helps with temporary relief, but resilience transforms challenges into lasting personal strength and life lessons.

Can resilience be taught in schools and workplaces?

Yes. Resilience can be developed in educational and professional settings by teaching problem-solving, emotional regulation, and social skills. Schools can design programs that encourage self-reflection, while workplaces can create resilience workshops, mentoring systems, and supportive cultures that empower employees to thrive despite challenges.

What role do relationships play in resilience?

Relationships are central to resilience. Supportive networks provide encouragement, comfort, and guidance. Family, friends, mentors, and communities help individuals feel less alone and more capable of handling hardship. In many cases, the presence of just one caring relationship can be a decisive factor in how resilient a person becomes.

How does culture influence resilience?

Culture shapes how people interpret and respond to adversity. Collective practices such as rituals, storytelling, and community support systems provide a shared sense of meaning. Cultural values also determine whether individuals seek help, remain private, or turn to spiritual beliefs in times of hardship. Respecting cultural differences is essential in promoting resilience.

What is the connection between resilience and mental health?

Resilience protects mental health by reducing vulnerability to long-term psychological problems such as depression or anxiety after adversity. People with high resilience are more likely to regulate emotions, maintain perspective, and seek support. However, being resilient does not mean being unaffected by stress. It means finding ways to recover and adapt without being permanently overwhelmed.

Can trauma ever strengthen resilience?

Yes, many people experience post-traumatic growth. This occurs when trauma, while painful, leads to deeper personal insight, stronger values, or renewed purpose in life. Survivors may develop compassion for others, new priorities, or spiritual strength. While trauma is never desirable, it can sometimes lead to resilience that would not have emerged otherwise.

Does age affect resilience?

Age and life stage strongly influence resilience. Children often rely heavily on family and community, while young adults may draw resilience from peer networks and emerging independence. Middle-aged adults may use life experience to navigate complex challenges, and older adults often rely on wisdom, perspective, and long-term coping strategies.

What practical steps can individuals take to strengthen their resilience?

Practical steps include maintaining healthy routines, practicing gratitude, setting achievable goals, and developing emotional awareness. Reflection practices such as journaling or meditation help regulate stress. Building supportive relationships, asking for help when needed, and creating meaning from life experiences are all strategies that nurture resilience over time.

Why is equity important when discussing resilience?

Equity ensures that everyone has the foundation needed to recover from adversity. Inequalities in access to housing, healthcare, and education create chronic stress that can undermine resilience. While personal strength is important, systemic barriers must also be addressed to give all individuals a fair opportunity to adapt and recover.

Can resilience prevent burnout in stressful jobs?

Yes. Resilience helps people manage high levels of stress without reaching the point of burnout. For example, healthcare workers, teachers, and first responders face constant challenges. Those with strong resilience are better at regulating emotions, maintaining balance, and seeking social support. Organizations that provide training and emotional resources further protect employees against burnout.

How does resilience affect physical health?

Resilience benefits physical health because it reduces the impact of stress on the body. Chronic stress weakens the immune system and increases the risk of illness. Resilient individuals use healthier coping strategies such as exercise, sleep, and positive social interactions, which lower stress hormones and strengthen overall well-being.

Are there cultural differences in how resilience is expressed?

Yes. Some cultures emphasize individual perseverance, while others stress collective strength. For example, in Western contexts resilience may be described as personal grit, whereas in many Indigenous or collectivist cultures, resilience is deeply tied to community, spirituality, and harmony with the environment. Both perspectives highlight that resilience is not one-size-fits-all but shaped by cultural identity.

What role does hope play in resilience?

Hope is central to resilience. It is the belief that even in hardship, life can still hold meaning and purpose. Hope provides motivation to endure challenges and a vision of a better future. Without hope, individuals may feel stuck, but with it, they can take steps toward recovery and growth.

Can resilience be measured scientifically?

Yes. Psychologists use resilience scales and questionnaires to assess levels of resilience in individuals or groups. These tools measure traits such as optimism, coping skills, and adaptability. Although resilience is complex and influenced by many factors, these assessments provide useful insights for therapy, research, and personal development.

Do resilient people still experience stress and negative emotions?

Absolutely. Being resilient does not mean being immune to stress, sadness, or fear. Instead, resilience allows individuals to experience these emotions without being consumed by them. Resilient people may still cry, feel anxious, or struggle, but they eventually regain balance and move forward with strength.

How can parents help children build resilience?

Parents play a crucial role in shaping resilience. By creating a supportive and nurturing environment, encouraging problem-solving, modeling healthy coping strategies, and providing consistent love and guidance, parents give children the tools to handle challenges. Allowing children to experience manageable difficulties also teaches them that they can overcome obstacles.

Can communities build resilience collectively?

Yes. Communities strengthen resilience by creating safe spaces, fostering trust, and offering resources such as counseling, education, and social programs. In times of crisis, communities that promote solidarity and cooperation recover more effectively. Shared rituals, cultural practices, and mutual aid all contribute to collective resilience.

What is the difference between resilience and toughness?

Toughness often implies suppressing emotions or enduring hardship without support. Resilience, in contrast, involves acknowledging emotions, seeking help when needed, and adapting constructively. While toughness can sometimes lead to isolation, resilience fosters connection, meaning, and personal growth.

Why is resilience important for long-term life satisfaction?

Resilience is essential for long-term well-being because it allows individuals to face life’s inevitable challenges with strength and adaptability. People who develop resilience are more likely to maintain healthy relationships, find meaning in their experiences, and sustain hope for the future. This not only helps them survive adversity but also thrive in the long run.

References:

- Lohner, M. S., & Aprea, C. (2021). The resilience journal: Exploring the potential of journal interventions to promote resilience in university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 702683. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.702683

- Sisto, A., Vicinanza, F., Campanozzi, L. L., Ricci, G., Tartaglini, D., & Tambone, V. (2019). Towards a transversal definition of psychological resilience: A literature review. Medicina, 55(11), 745. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55110745

- Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), Article 25338. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College