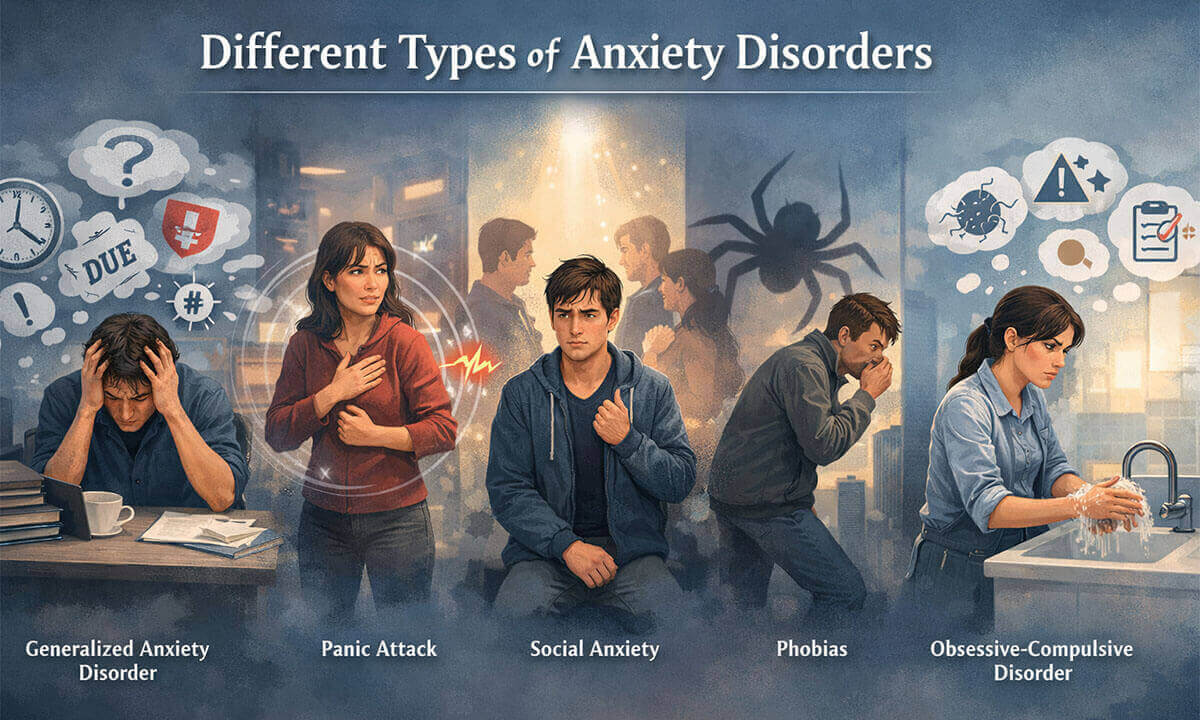

Different Types of Anxiety Disorders:

Anxiety is a natural and even necessary part of being human. It alerts us to danger, sharpens our focus, and prepares our bodies to respond when something feels threatening. In small doses, this stress response is protective and adaptive. However, when anxiety becomes persistent, overwhelming, and disconnected from real or immediate danger, it can begin to disrupt daily life, affecting work performance, relationships, physical health, and overall well-being. Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health conditions worldwide, affecting millions of people across cultures and age groups. Despite their prevalence and the fact that they are highly treatable through therapy, medication, and practical coping strategies, many individuals struggle in silence due to stigma or lack of awareness. Understanding the different types of anxiety disorders is an important first step toward recognizing symptoms, seeking appropriate support, and promoting recovery.

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): is characterized by excessive, uncontrollable worry about multiple areas of life. Unlike situational anxiety, which arises in response to a clear stressor, GAD involves ongoing worry that feels constant and difficult to switch off. Individuals with GAD often anticipate worst-case scenarios related to work, finances, health, family, or everyday responsibilities; even when there is little objective reason for concern (Meares & Freeston, 2015).

What makes GAD particularly distressing is not just the content of the worries but their persistence. People frequently describe feeling “on edge” most of the time, unable to relax even during calm periods. The mind may constantly scan for potential threats, creating a sense of impending doom that is hard to rationalize away.

Physically, GAD can take a significant toll. Common symptoms include restlessness, muscle tension, digestive discomfort, sleep disturbances, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, appetite changes, and a sense of mental fog. Over time, chronic activation of the stress response can impair both mental clarity and physical wellbeing. Everyday tasks (such as completing work assignments, making decisions, or engaging in social interactions) can feel overwhelming.

Importantly, GAD is not a personality flaw or a sign of weakness. It is a recognized mental health condition that responds well to treatment. Evidence-based approaches, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), medication when appropriate, and lifestyle interventions, can significantly reduce symptoms and improve quality of life (Antony & Norton, 2015).

- Panic Disorder: involves recurrent and unexpected panic attacks; intense surges of fear that peak within minutes. These attacks can feel terrifying and may occur without any obvious external trigger. During a panic attack, individuals often experience symptoms such as a racing or pounding heart, chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, trembling, sweating, nausea, or a feeling of losing control. Some fear they are having a heart attack, going crazy, or about to die (Barlow & Craske, 2022).

A single panic attack does not necessarily mean someone has panic disorder. The disorder develops when a person becomes persistently worried about having additional attacks and begins changing their behavior to avoid them. This anticipatory anxiety can be just as disruptive as the attacks themselves.

Individuals may avoid crowded places, public transportation, driving, traveling, or being alone in unfamiliar environments. Over time, this avoidance can shrink their world, limiting independence and reinforcing fear. The more situations are avoided, the more threatening they can seem.

Despite its intensity, panic disorder is highly treatable. Interventions such as CBT, interoceptive exposure (gradually confronting feared bodily sensations), breathing techniques, grounding exercises, and medication can significantly reduce the frequency and severity of attacks (Fletcher, 2019). With consistent treatment, many people regain confidence and return to activities they once avoided.

- Social Anxiety Disorder: goes far beyond ordinary shyness. It involves intense fear of being judged, embarrassed, criticized, or negatively evaluated in social or performance situations. Everyday interactions (meeting new people, speaking in meetings, eating in public, or even making small talk) can trigger overwhelming anxiety (Barlow & Craske, 2022).

Individuals with social anxiety often engage in harsh self-monitoring, analyzing how they appear to others, and fearing they will say or do something humiliating. This internal focus can make it difficult to stay present in conversations, further increasing anxiety.

Physical symptoms are common and may include blushing, sweating, shaking, difficulty speaking, nausea, or a racing heart. Some individuals avoid social situations altogether, which can affect relationships, academic performance, and career opportunities. Others may rely on alcohol or substances as a coping mechanism, potentially leading to additional problems.

Social anxiety disorder is not simply a matter of “trying harder” to be confident. It is a well-documented mental health condition that can be effectively treated. Gradual exposure to feared situations, cognitive restructuring to challenge negative beliefs, social skills training, and medication when appropriate have been shown to reduce symptoms and improve functioning (Bourne, 2015).

- Phobias: A phobia is an intense, disproportionate fear of a specific object, situation, or activity that poses little or no actual danger. Common examples include fears of spiders, heights, flying, needles, or enclosed spaces. While many people have mild fears or dislikes, a phobia produces an extreme anxiety response that can resemble a panic attack (Antony & Norton, 2015).

Individuals with phobias often recognize that their fear is irrational, yet this awareness does not eliminate the anxiety. The emotional and physiological response (racing heart, sweating, trembling, dizziness, or a strong urge to escape) can be overwhelming.

Avoidance is a key feature. Someone afraid of flying may refuse travel opportunities; a person with a needle phobia might avoid necessary medical care. In severe cases, phobias can significantly restrict life choices and opportunities.

Fortunately, phobias are among the most treatable anxiety disorders. Graded exposure therapy (systematically and gradually confronting the feared object or situation in a controlled manner) has strong evidence supporting its effectiveness. When combined with anxiety management techniques, exposure can help retrain the brain’s fear response and substantially reduce or even eliminate the phobia over time (Bourne, 2015).

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): involves a cycle of intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions) performed to reduce anxiety. Obsessions may center on contamination, safety, symmetry, morality, or fears of harming oneself or others. These thoughts are unwanted and distressing, and individuals typically recognize that they are excessive or irrational (Pittman & Karle, 2015).

Compulsions are attempts to neutralize or reduce the distress caused by these thoughts. They may include excessive cleaning, repeated checking, counting, arranging objects, or seeking reassurance. While these behaviors temporarily relieve anxiety, the relief is short-lived, reinforcing a repetitive and time-consuming cycle.

OCD can significantly interfere with daily life, consuming hours each day and impacting work, school, and relationships. It is not simply about being neat, orderly, or conscientious. Rather, it is a distressing condition marked by intrusive fears and compulsive rituals.

Evidence-based treatments such as exposure and response prevention (ERP), a specialized form of CBT, have been shown to be highly effective. By gradually confronting feared thoughts or situations while resisting compulsive behaviors, individuals can reduce anxiety and weaken the obsessive-compulsive cycle. Medication may also be helpful for some individuals (Pittman & Karle, 2015).

Causes and Risk Factors of Anxiety Disorders:

Anxiety disorders do not arise from a single cause. Instead, they develop through a complex interaction of biological vulnerabilities, psychological patterns, and environmental stressors. For some individuals, anxiety may appear to emerge suddenly; for others, it builds gradually over time. Understanding these contributing factors can reduce self-blame and promote early, effective intervention.

- Biological and Genetic Factors: Research suggests that genetics play a meaningful role in the development of anxiety disorders. Individuals with a family history of anxiety are at greater risk of experiencing similar difficulties themselves (McLaughlin et al., 2008). This does not mean that anxiety is inevitable, but it does suggest a biological sensitivity in how the brain processes fear and stress.

Neurobiologically, anxiety disorders are linked to differences in how the brain regulates threat detection and emotional responses. Systems involving the amygdala (which processes fear), the prefrontal cortex (which regulates emotional reactions), and stress hormones such as cortisol may function in a heightened or dysregulated way. This can make certain individuals more reactive to perceived danger, even in relatively safe environments. When this biological sensitivity is combined with environmental stress, anxiety symptoms are more likely to develop.

- Psychological Factors: Personality traits and cognitive styles also influence vulnerability. Individuals who are naturally more cautious, sensitive to criticism, or prone to excessive worry may be at increased risk. Low self-confidence, perfectionism, or a strong need for control can amplify anxious thoughts, especially in uncertain situations.

Cognitive patterns (such as catastrophizing (expecting the worst), overgeneralizing from negative experiences, or constantly scanning for potential threats) can strengthen anxiety over time. Once these thinking habits become ingrained, they reinforce the body’s stress response, creating a cycle that is difficult to break.

Importantly, these traits are not weaknesses. In many contexts, being vigilant or detail-oriented can be strengths. However, when combined with chronic stress or trauma, they can contribute to persistent anxiety.

- Environmental and Life Experiences: Life experiences play a critical role in shaping anxiety risk. Stressful or traumatic events (such as abuse, bullying, serious illness, injury, bereavement, or sudden major life transitions) can significantly increase vulnerability (McLaughlin et al., 2008). Even positive life changes, such as starting a new job or moving to a new city, can be destabilizing if they involve high uncertainty or pressure.

Chronic stress is particularly influential. Ongoing exposure to workplace pressure, academic demands, financial instability, or family conflict can gradually wear down coping resources. When stress accumulates without adequate recovery or support, the nervous system may remain in a prolonged state of alertness, increasing the likelihood of developing an anxiety disorder.

Early childhood adversity can also shape long-term stress responses. Repeated exposure to unpredictable or threatening environments during formative years may sensitize the brain’s fear system, making it more reactive later in life.

- Medical and Lifestyle-Related Risk Factors: Certain medical conditions (such as chronic pain, hormonal imbalances, cardiovascular issues, or respiratory disorders) can contribute to anxiety symptoms. The physical sensations associated with illness (e.g., shortness of breath, heart palpitations) may mimic anxiety, which can in turn increase fear and worry.

Substance use is another important risk factor. While alcohol or drugs may initially be used to cope with stress, they can disrupt brain chemistry and worsen anxiety over time. Withdrawal from certain substances can also intensify anxious symptoms.

According to Barlow and Craske (2022), anxiety disorders are more likely to develop when multiple vulnerabilities overlap. For example, a person with a genetic predisposition who experiences trauma and ongoing stress may be at significantly higher risk than someone exposed to only one of these factors.

- The Interaction of Multiple Factors: Rarely does a single event or trait cause an anxiety disorder. Instead, anxiety typically emerges from the interaction of several influences; biological sensitivity, learned patterns of thinking, and environmental stressors working together. This “multiple pathways” perspective helps explain why anxiety presents differently from person to person.

Encouragingly, just as anxiety develops through interacting factors, recovery can also be approached from multiple angles. Therapy can address cognitive patterns, lifestyle changes can reduce stress, and medical treatment can support biological regulation.

In conclusion, anxiety is a natural and protective part of being human, it alerts us to danger and prepares us to respond to challenges. However, when anxiety becomes persistent, excessive, and disconnected from real or immediate threats, it can begin to interfere with daily life. For many individuals, this ongoing state of worry is not simply a reaction to circumstances but may stem from underlying biological vulnerabilities, heightened stress responses, or patterns of negative, worst-case thinking. Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health conditions worldwide, and they often coexist with other psychological or physical health concerns. The encouraging news is that they are highly treatable. With appropriate support, therapy, coping strategies, and sometimes medication, many people experience significant improvement, and many go on to make a full recovery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Is anxiety always a mental health disorder?

No, anxiety is a normal and healthy response to stress or danger. It becomes a disorder when it is persistent, excessive, difficult to control, and interferes with daily functioning.

What is the difference between normal worry and an anxiety disorder?

Normal worry is temporary and linked to specific situations. An anxiety disorder involves ongoing fear or worry that feels overwhelming, disproportionate to the situation, and hard to manage.

Can anxiety disorders go away on their own?

Mild anxiety may improve with lifestyle changes and stress reduction. However, persistent or severe anxiety disorders often require professional support, such as therapy or medication, for lasting improvement.

Are anxiety disorders treatable?

Yes, anxiety disorders are highly treatable. Evidence-based therapies, coping strategies, and sometimes medication can significantly reduce symptoms, and many people recover fully.

Can anxiety disorders occur alongside other conditions?

Yes, anxiety disorders commonly coexist with depression, substance use disorders, and certain physical health conditions. Treating all coexisting conditions is important for effective recovery.

When should someone seek professional help?

It is advisable to seek help when anxiety becomes frequent, overwhelming, affects sleep or concentration, interferes with work or relationships, or leads to avoidance of daily activities.

Can lifestyle changes help manage anxiety?

Yes, regular exercise, adequate sleep, balanced nutrition, relaxation techniques, mindfulness practices, and reducing caffeine or substance use can support anxiety management alongside professional treatment.

References:

- Antony, M. M., & Norton, P. J. (2015). The anti-anxiety workbook: Proven strategies to overcome worry, phobias, panic, and obsessions (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Barlow, D. H., & Craske, M. G. (2022). Mastery of your anxiety and panic: Workbook. Oxford University Press.

- Bourne, E. J. (2015). The anxiety and phobia workbook (6th ed.). New Harbinger Publications.

- Fletcher, J. (2019). Anxiety: Practical about panic: A practical guide to understanding and overcoming anxiety disorder. John Murray One.

- Global Disease Burden (GBD) 2021 (2024). Seattle: Institute for health metrics and evaluation. Retrieved from https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/

- McLaughlin, K. A., Behar, E., & Borkovec, T. D. (2008). Family history of psychological problems in generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(7), 905–918. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20497

- Meares, K., & Freeston, M. (2015). Overcoming worry and generalised anxiety disorder: A self-help guide using cognitive behavioural techniques (2nd ed.). Robinson.

- Pittman, C. M., & Karle, E. M. (2015). Rewire your anxious brain: How to use the neuroscience of fear to end anxiety, panic, and worry. New Harbinger Publications.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College