Emotional blackmail is a powerful form of manipulation that can deeply affect relationships, personal well-being, and decision-making. Whether in friendships, workplaces, or family dynamics, many people have experienced situations where they feel pressured to comply with someone else’s demands out of guilt, fear, or obligation (Forward, 1997; Najem & Abbas, 2024). These tactics often exploit our emotional connections, making it difficult to assert personal boundaries or prioritize self-care. Recognizing emotional blackmail is the first step toward breaking free from its cycle. Understanding its causes, patterns, and effects can empower individuals to set healthier boundaries and resist manipulation. This article explores emotional blackmail including its stages, types, causes & how to deal with emotional blackmail.

What Is Emotional Blackmail?

Emotional blackmail, also referred to as emotional manipulation, is a coercive psychological strategy used to control others through guilt, fear, or obligation, often occurring in various life domains and negatively impacting the victim’s well-being and relationships (Kao, 2024; Najem & Abbas, 2024).

Susan Forward (1997) provides a foundational definition, describing emotional blackmail as “a powerful form of manipulation in which people close to us threaten, either directly or indirectly, to punish us if we don’t do what they want.” This type of manipulation often takes place in close relationships, where the blackmailer leverages emotional connections to enforce compliance. Common tactics include guilt-tripping statements such as “If you really loved me, you would do this” or accusations of selfishness to instill doubt and obligation in the victim (Forward, 1997).

Recent research expands the concept beyond personal relationships, identifying emotional blackmail within professional settings. In workplace environments, blackmailers manipulate colleagues to fulfill their demands, leaving the victim feeling frustrated, suppressed, and powerless (Kao, 2024). Furthermore, emotional blackmail does not always rely on threats alone—it can also involve promises of rewards or suggestions of positive outcomes to encourage compliance (Najem & Abbas, 2024).

Blackmailers often employ various manipulative techniques, including threats of retaliation (“I’ll make sure you never get to see the kids”), threats of self-harm (“If I do something to myself, it’s on your head”), guilt-tripping (“How can you be so selfish?”), playing the victim (“You have caused all of my suffering”), and distorting reality (“I’m not hurting anyone. I’ve always put you first”) (Forward, 1997). These tactics are often linked to deeper psychological issues such as narcissism, where individuals possess an inflated sense of self-importance and a lack of empathy, leading them to exploit others for personal gain (Forward, 1997).

Recognizing and understanding emotional blackmail is crucial for breaking free from manipulative cycles, setting boundaries, and fostering healthier relationships.

The Six Stages of Emotional Blackmail:

Susan Forward (1997) outlines six distinct stages through which both the emotional blackmailer and their victim progress. Understanding these stages is essential for recognizing manipulation and breaking free from its cycle.

1. Demand: The emotional blackmailer initiates the process by making a demand, expectation, or threat. This demand is often framed in a way that creates urgency or pressure, leaving little room for negotiation. The request may be unreasonable, violating the victim’s personal boundaries, needs, or well-being.

Example: A partner demands that their significant other cut ties with a close friend, saying, “If you really love me, you wouldn’t spend time with them.” Here, the blackmailer uses emotional attachment as leverage to control the victim’s social interactions.

2. Resistance: At this stage, the victim expresses hesitation, reluctance, or outright disagreement with the demand. They may attempt to assert their boundaries or voice their concerns. However, the blackmailer refuses to acknowledge their perspective and dismisses any attempts to negotiate or compromise.

Example: The victim responds, “But they’ve been my friend for years. I don’t think it’s fair for you to ask me to stop seeing them.” The blackmailer, unwilling to accept this resistance, moves to the next stage to break the victim’s resolve.

3. Pressure: When faced with resistance, the emotional blackmailer escalates their manipulation. They may employ guilt, fear, or obligation to coerce the victim into compliance. This stage often involves indirect persuasion, passive-aggressive remarks, or dramatic emotional displays.

Example: The blackmailer says, “I guess I just don’t matter to you. You’d rather choose them over me.” This attempt to guilt-trip the victim forces them to feel responsible for the blackmailer’s emotions.

4. Threats: As pressure intensifies, the blackmailer may escalate to direct or indirect threats. These threats can take different forms, such as:

- Retaliation threats: “If you don’t do what I want, I’ll make sure you regret it.”

- Self-harm threats: “If I do something to myself, it will be your fault.”

- Guilt-tripping: “After everything I’ve done for you, this is how you treat me?”

- Playing the victim: “You’re so selfish. I sacrifice everything for you, and you don’t even care.”

Example: The partner now says, “If you don’t stop seeing that friend, I don’t know if I can stay in this relationship. Maybe I should just leave.” Here, they make an implicit threat of abandonment, forcing the victim to choose between compliance and losing the relationship.

5. Compliance: The victim, feeling emotionally exhausted and cornered, gives in to the blackmailer’s demand. Compliance often comes at the cost of their self-esteem, autonomy, and personal boundaries. However, the victim may justify their decision as a way to avoid further conflict, believing that giving in will bring peace.

Example: The victim, overwhelmed by guilt and fear, says, “Fine, I’ll stop talking to them.” In doing so, they unknowingly reinforce the blackmailer’s control, signaling that such manipulative tactics are effective.

6. Repetition: Once the blackmailer successfully coerces the victim into compliance, they recognize their power and continue using emotional blackmail in the future. The cycle repeats itself, often with increasing intensity, as the victim becomes more conditioned to giving in under pressure.

Example: The blackmailer later makes another unreasonable demand, such as controlling the victim’s clothing choices, social activities, or career decisions. Because the victim has complied in the past, the blackmailer assumes they will do so again, further deepening the cycle of manipulation.

Types of Emotional Blackmail:

Susan Forward (1997) identifies four primary types of emotional blackmailers: Punishers, Self-Punishers, Sufferers, and Tantalizers. Each type employs distinct strategies to manipulate their targets, and understanding these categories is essential for recognizing and addressing such behaviors in various relationships.

1. Punishers: Punishers use direct threats and aggressive tactics to ensure compliance. They operate with a “do as I say or face the consequences” mentality, making it clear that non-compliance will lead to negative outcomes. This approach often involves overt expressions of anger, verbal abuse, or the silent treatment to instill fear and pressure the victim into submission.

Example: A parent might say, “If you marry that person, I will cut you off financially and never speak to you again.” In this scenario, the parent uses the threat of financial and emotional abandonment to manipulate their child’s marital choices.

2. Self-Punishers: Self-Punishers turn threats inward, suggesting they will harm themselves if their demands are not met. This form of manipulation exploits the victim’s sense of responsibility and guilt, making them feel obligated to comply to prevent the blackmailer from self-harm. It’s a particularly insidious tactic because it places the victim in a position where they feel solely responsible for the blackmailer’s well-being.

Example: A partner might say, “If you leave me, I don’t know how I’ll go on. I might as well end it all.” This statement places the burden of the blackmailer’s mental health and survival on the victim, coercing them into staying in the relationship out of fear and guilt.

3. Sufferers: Sufferers present themselves as perpetual victims, emphasizing their own pain or hardships to elicit guilt and compliance from others. They often imply that their suffering is the direct result of the victim’s actions or decisions, making the victim feel responsible for alleviating their distress. This type of blackmailer uses their suffering as a tool to manipulate, often exaggerating or fabricating issues to gain sympathy and control.

Example: A friend might say, “I’ve been so depressed and lonely lately, and you haven’t been there for me. If you really cared, you’d spend more time with me.” Here, the friend implies that their emotional distress is due to the victim’s lack of attention, guilting them into prioritizing the blackmailer’s needs over their own.

4. Tantalizers: Tantalizers use promises of rewards or positive outcomes to manipulate others. They dangle the prospect of something desirable but make it contingent upon the victim’s compliance with their wishes. This type of blackmail is particularly deceptive because it exploits the victim’s hopes and desires, leading them to believe that fulfilling the blackmailer’s demands will result in a beneficial outcome.

Example: A supervisor might say, “If you take on this additional project and work overtime, I’ll consider you for a promotion.” In this case, the promise of career advancement is used to pressure the employee into accepting extra work, even though there’s no guarantee the reward will materialize.

Causes of Emotional Blackmail:

Emotional blackmail arises from a complex interplay of psychological, emotional, and relational factors. While blackmailers are often motivated by fear, insecurity, and desperation, their actions are also shaped by deep-seated personal vulnerabilities and relational dynamics (Kao, 2024).

Psychological Factors Contributing to Emotional Blackmail: Emotional blackmail is deeply rooted in psychological tendencies and personality traits that shape how individuals interact in relationships. Certain psychological factors make some individuals more prone to using manipulation as a means of control. These factors include:

- Low Self-Esteem: Individuals with low self-esteem often struggle with feelings of inadequacy and unworthiness. They may resort to emotional blackmail as a way to gain validation, seeking reassurance by manipulating others into meeting their emotional needs.

For instance, a partner with low self-esteem might say, “If you really loved me, you would do this for me,” framing their insecurity as a test of loyalty. By inducing guilt, they aim to receive affirmation and reinforce their self-worth.

- Need for Control: A strong need for control often drives individuals to manipulate others. Blackmailers may fear unpredictability and rejection, leading them to use coercive tactics to maintain dominance in their relationships.

For example, a controlling spouse might say, “If you leave me, I will ruin your reputation,” using threats to prevent their partner from making independent choices. This need for control stems from an internal fear of losing power over the relationship dynamic.

- Low Tolerance for Frustration: Some emotional blackmailers struggle with emotional regulation and have difficulty coping with disappointment. When faced with resistance, they may resort to manipulative behaviors to force compliance rather than accepting situations that do not go in their favor.

For example, a parent with low frustration tolerance might say, “If you don’t obey me, don’t expect me to support you anymore,” using emotional pressure to ensure their demands are met. This behavior reflects their inability to handle opposition in a mature manner.

- Exploitation of Others’ Vulnerabilities: Emotional blackmailers are often highly perceptive of their victims’ emotional weaknesses. They exploit vulnerabilities such as guilt, fear, or a strong sense of duty to gain control.

For instance, a manipulative boss might say, “I thought you were a team player. If you really cared about this company, you’d work overtime,” using an employee’s dedication to their job as a tool for coercion. By identifying what their victim values most, blackmailers can effectively manipulate their actions.

- Distorted Perception of Love and Obligation: Some individuals view love as a transactional or obligatory force rather than a mutual and respectful bond. They believe that others should meet their needs unconditionally, using emotional manipulation to ensure compliance.

For example, a family member might say, “After everything I’ve done for you, you owe me this,” leveraging past sacrifices as a justification for their demands. This perception reduces relationships to a system of control rather than mutual care and respect.

Victim Vulnerabilities Exploited by Blackmailers: Emotional blackmailers often target specific vulnerabilities in their victims, making them more susceptible to manipulation. These vulnerabilities stem from personality traits, emotional tendencies, and life experiences that make individuals more likely to comply with coercive demands (Forward, 1997).

- Strong Need for Approval: Individuals with a deep desire for validation often find it difficult to say no, fearing that rejection will make them unworthy or unloved. Blackmailers exploit this need by making their victims feel guilty or selfish if they refuse a demand.

For example, a manipulative partner might say, “If you truly cared about me, you would do this,” knowing that their victim will comply to avoid feeling unloved or unappreciated.

- Fear of Conflict: Some people have an intense aversion to confrontation and will go to great lengths to avoid disagreements. Blackmailers take advantage of this by using intimidation, guilt, or passive-aggressive tactics to ensure compliance.

For instance, an emotionally manipulative friend might say, “If you don’t lend me the money, I don’t know how I’ll ever trust you again,” knowing that the victim will comply rather than endure an uncomfortable conflict.

- Prioritizing Peace Over Personal Needs: Many individuals are willing to sacrifice their own well-being in order to maintain harmony in their relationships. This self-sacrificing tendency makes them easy targets for emotional blackmail, as blackmailers pressure them into compliance by creating emotional distress.

For example, a controlling parent might say, “If you don’t do what I ask, you’ll break this family apart,” forcing their child to ignore personal boundaries to preserve family peace.

- High Levels of Self-Doubt: People who frequently second-guess their own decisions or struggle with low confidence are more likely to fall victim to manipulation. Blackmailers take advantage of this uncertainty by making their victims feel as though they are being unreasonable or overreacting.

For instance, a toxic colleague might say, “You’re overthinking this—why are you being so dramatic?” to make their victim question their instincts and comply with their demands.

- Excessive Responsibility for Others’ Happiness: Some individuals feel deeply responsible for the emotions and well-being of those around them. Emotional blackmailers exploit this sense of duty by making their victims believe they are the sole cause of their happiness or suffering.

For example, a manipulative partner might say, “If you leave me, I’ll be devastated, and it will all be your fault,” making the victim feel personally responsible for their emotional state.

- Fear of Exposure: Blackmailers sometimes use threats of revealing personal information, secrets, or past mistakes to gain control over their victims. The fear of humiliation or damaged reputations makes individuals more likely to comply with unreasonable demands.

For instance, a former friend who knows personal details might say, “If you don’t do this for me, I might accidentally mention what you told me in confidence,” using the fear of exposure as a manipulative tool.

Additional Psychological Factors Contributing to Emotional Blackmail: While emotional blackmail is often associated with control, fear, and insecurity, additional psychological factors can also play a role. Research suggests that certain personality disorders and attachment styles contribute to manipulative behaviors, particularly in close relationships.

- Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and Emotional Manipulation: Individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) often struggle with intense and unstable emotions, leading to difficulty in maintaining healthy relationships. Their relationships frequently shift between idealization (seeing someone as perfect) and devaluation (seeing them as worthless), creating emotional turbulence that fosters manipulative behaviors (Kuo et al., 2015).

People with BPD fear abandonment deeply, and when they perceive rejection—whether real or imagined—they may resort to emotional blackmail as a way to prevent loss. Their reactions can be extreme, often involving threats of self-harm, guilt-tripping, or blaming others for their distress (Kuo et al., 2015).

Example: A person with BPD might tell their partner, “If you leave me, I don’t know what I’ll do. I might hurt myself, and it will be your fault.” This statement combines fear, guilt, and coercion, making the victim feel responsible for their well-being and pressuring them to stay in the relationship.

Additionally, because individuals with BPD have difficulty regulating emotions, their responses to perceived rejection can be impulsive and emotionally charged. For example, a friend with BPD might suddenly withdraw affection, saying, “I thought you were different, but I see now that you’re just like everyone else. I can’t believe I trusted you.” This reaction manipulates the other person into proving their loyalty, even at the expense of their own well-being.

- Attachment Styles and Emotional Coercion: Attachment theory suggests that the way individuals form emotional bonds in childhood influences their relationships in adulthood. Studies indicate that individuals with anxious or avoidant attachment styles are more likely to engage in emotional blackmail due to their fear of rejection and difficulty managing emotional conflict (Bonache et al., 2019).

- Anxious Attachment: People with this attachment style crave closeness but fear abandonment. They may use guilt, excessive emotional displays, or threats to keep loved ones from leaving.

- Avoidant Attachment: These individuals struggle with emotional intimacy and may use emotional withdrawal or manipulation to maintain control over relationships.

Example of Anxious Attachment: A person with anxious attachment might say, “If you really cared about me, you wouldn’t need time alone. Why are you trying to push me away?” This statement pressures the other person to prioritize the blackmailer’s emotional needs over their own personal space.

Example of Avoidant Attachment: Someone with avoidant attachment might use distancing tactics to create insecurity in their partner. For instance, they might refuse to communicate or withhold affection, leading their partner to feel desperate for reassurance. If their partner expresses concern, they might respond with, “You’re being too needy. Maybe we’re not right for each other.” This subtle manipulation forces the victim to suppress their own needs to avoid conflict or rejection.

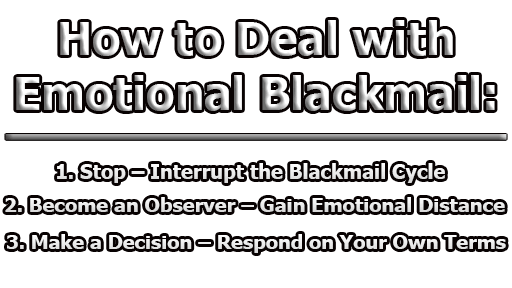

How to Deal With Emotional Blackmail:

Emotional blackmail can be deeply distressing, leaving victims feeling trapped and powerless. However, by following a structured approach, individuals can regain control, set boundaries, and respond in a way that prioritizes their well-being. The following steps, adapted from Forward (1997), offer a reliable and repeatable strategy for handling emotional blackmail effectively.

1. Stop – Interrupt the Blackmail Cycle: One of the most crucial steps in dealing with emotional blackmail is breaking the automatic reaction that the blackmailer expects. Many victims comply instinctively out of fear, guilt, or anxiety, but this reinforces the blackmailer’s power. Instead of responding immediately, the victim must create space to reflect.

Using delay tactics can help stop the manipulation before it escalates. Responses like:

- “I can’t answer you right now, so I’m taking time to think this over.”

- “This is too important to decide quickly. Let me stop and think about it.”

- “I’m not willing to make that decision right now.”

These statements serve two purposes: they disrupt the expected dynamic (where the victim automatically complies) and buy time for rational decision-making rather than reacting emotionally.

Example: If a controlling friend says, “If you don’t come to my party, then I’ll know you don’t care about me,” instead of responding immediately out of guilt, the victim can say, “I need to check my schedule and get back to you.” This shifts the power dynamic and prevents emotional coercion from dictating the outcome.

2. Become an Observer – Gain Emotional Distance: Once the immediate pressure is lifted, the next step is to step back and analyze the situation objectively. This requires detaching from the emotional manipulation and evaluating the blackmailer’s behavior logically.

Techniques for Emotional Detachment:

- Visualization Exercise: Forward (1997) suggests picturing oneself in an elevator rising above the fog, symbolizing moving away from the confusion and emotions of the situation toward clarity.

- Third-Person Perspective: Mentally viewing the situation as an outsider can help identify patterns of manipulation.

- Journaling: Writing down the details of the interaction can clarify what is happening and prevent emotional bias from influencing decisions.

Once emotionally detached, the victim should ask themselves:

- What exactly is being asked of me?

- How was the request made—through guilt, threats, or fear?

- How did the blackmailer react when I didn’t immediately agree?

Example: If a family member says, “If you don’t lend me money, you obviously don’t love me,” the victim can take a step back and analyze:

- Is this a reasonable request?

- Am I being pressured through guilt?

- How does this make me feel?

By observing rather than reacting, the victim can make a more conscious decision rather than falling into the emotional trap.

3. Make a Decision – Respond on Your Own Terms: Once the victim has assessed the situation, they can decide whether to comply, negotiate, or set boundaries based on their own values and needs rather than fear or guilt. The key is making a conscious decision, rather than acting out of emotional pressure.

Options for Responding:

- Agreeing with Conditions: If compliance is the best choice, it should be done on the victim’s terms.

“I can help you, but only if you respect my limits and don’t pressure me next time.”

- Compromising: Offering a solution that works for both parties while maintaining personal boundaries.

“I can’t give you money, but I can help you look for financial resources.”

- Declining with Explanation: Clearly stating personal limits without defensiveness.

“I understand that you’re upset, but I’m not comfortable doing this.”

The tone of delivery is essential—calm, firm, and without justification beyond what is necessary. Victims should avoid becoming defensive, as this can fuel the blackmailer’s manipulation.

Example: If a partner says, “If you don’t quit your job, I’ll leave you,” instead of reacting with fear or guilt, the victim can say, “I understand that you have concerns, but my job is important to me. I won’t quit, and I hope we can find a way to discuss this respectfully.”

Setting clear boundaries at this stage prevents the cycle from repeating. The victim must stand by their decision without wavering, as inconsistency can encourage further manipulation.

In conclusion, emotional blackmail thrives on control and manipulation, often exploiting the victim’s emotional vulnerabilities. The more a victim complies, the stronger the blackmailer’s influence becomes, reinforcing a destructive cycle. Breaking free requires awareness, the ability to recognize manipulative patterns, and the confidence to set firm boundaries. By pausing before reacting and making decisions on their own terms, victims can regain control over their choices and emotional well-being. Supporting individuals in navigating and overcoming emotional blackmail empowers them to build healthier, more balanced relationships based on mutual respect rather than coercion.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Is emotional blackmail a crime?

Emotional blackmail itself is not always classified as a crime, but it can be linked to unlawful behaviors such as coercion, blackmail, harassment, or domestic abuse, depending on the severity and circumstances. In some cases, threats of self-harm, intimidation, or manipulation may cross legal boundaries, especially if they involve extortion, financial control, or psychological abuse.

What are the signs of emotional blackmail?

Some common signs of emotional blackmail include:

- Guilt-tripping: Making you feel responsible for their happiness or well-being.

- Threats: Implicit or explicit threats of self-harm, retaliation, or withdrawal of love.

- Playing the victim: Blaming you for their suffering to manipulate your actions.

- Distorting reality: Denying past behavior, rewriting events, or making you doubt yourself.

- Increasing pressure: Repeatedly demanding compliance and escalating emotional tactics if you resist.

How can I recognize if I unintentionally use emotional blackmail in my relationships?

If you find yourself frequently using guilt, threats, or emotional pressure to influence others, you may be engaging in emotional blackmail. Ask yourself:

- Do I make others feel guilty to get what I want?

- Do I use phrases like “If you really loved me, you would…”?

- Do I react negatively when someone sets boundaries with me?

- Do I feel the need to control others’ decisions to feel secure?

Recognizing these behaviors is the first step toward healthier, more respectful communication in relationships.

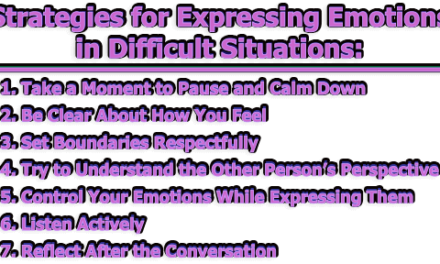

How can I respond to emotional blackmail?

To protect yourself from emotional blackmail, you can:

- Pause before responding: Avoid giving in to immediate emotional pressure.

- Set boundaries: Clearly communicate what you will and will not tolerate.

- Stay calm and assertive: Refuse to be manipulated while remaining respectful.

- Seek support: Talk to a trusted friend, therapist, or support group.

Can emotional blackmail happen in the workplace?

Yes, emotional blackmail is not limited to personal relationships. In the workplace, it can involve a boss, colleague, or subordinate using guilt, threats, or manipulation to control your actions. Examples include pressuring you into working overtime under guilt-based reasoning (“If you don’t stay late, you’re letting the team down”) or using emotional appeals to avoid accountability (“I thought you were my friend, how could you report me?”).

Is emotional blackmail the same as manipulation?

Emotional blackmail is a form of manipulation, but not all manipulation is emotional blackmail. Emotional blackmail specifically involves using fear, guilt, or obligation to control someone’s behavior, often in close relationships. Other forms of manipulation can include deceit, gaslighting, or passive-aggressive behavior.

How does emotional blackmail affect mental health?

Victims of emotional blackmail may experience:

- Anxiety and stress

- Low self-esteem and self-doubt

- Depression and feelings of helplessness

- Difficulty setting boundaries in relationships

Long-term exposure can lead to emotional exhaustion and difficulty trusting others. Seeking therapy or support can help rebuild confidence and establish healthier relationship patterns.

How can I help someone who is being emotionally blackmailed?

If you know someone struggling with emotional blackmail:

- Listen without judgment: Allow them to share their experience without feeling blamed.

- Encourage self-reflection: Help them recognize manipulative patterns.

- Support their boundaries: Encourage them to say no without guilt.

- Suggest professional help: Therapy can be a valuable tool for regaining control and self-worth.

References:

- Al-Kreimeen, R. A., Alghafary, N. A., & Samawi, F. S. (2022). The association of emotional blackmail and adjustment to college life among warned female students at Al-Balqa University. Health Psychology Research, 10(3), 34109. https://doi.org/10.52965/001c.34109

- Bonache, H., Gonzalez-Mendez, R., & Krahé, B. (2019). Adult attachment styles, destructive conflict resolution, and the experience of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(2), 287–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516640776

- Ding, C., Zhang, J., & Yang, D. (2018). A pathway to psychological difficulty: Perceived chronic social adversity and its symptomatic reactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 615. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00615

- Forward, S. (1997). Emotional blackmail. Bantam.

- Kao, F.-H. (2024). Workplace emotional blackmail: conceptual clarification and development. Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N.J.), 43(30), 24809–24822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06172-5

- Kuo, J. R., Khoury, J. E., Metcalfe, R., Fitzpatrick, S., & Goodwill, A. (2015). An examination of the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and borderline personality disorder features: The role of difficulties with emotion regulation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 39, 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.08.008

- Lo, W. Y., Lin, Y. K., Lin, C. Y., & Lee, H. M. (2022). Invisible erosion of human capital: The impact of emotional blackmail and emotional intelligence on nurses’ job satisfaction and turnover intention. Behavioral Sciences (Basel), 13(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010037

- Mukhtar, S. (2023). Public health aspects of domestic/intimate partner violence abuse and trauma (DIVAT) during COVID-19 quarantine: Imbalanced power dynamic and sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 35(4), 301–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/10105395231164439

- Najem, A. S., & Abbas, N. F. (2024). Emotional blackmail in breaking bad series: A pragma-stylistic study. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 15(4), 1062–1071. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1504.04

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College