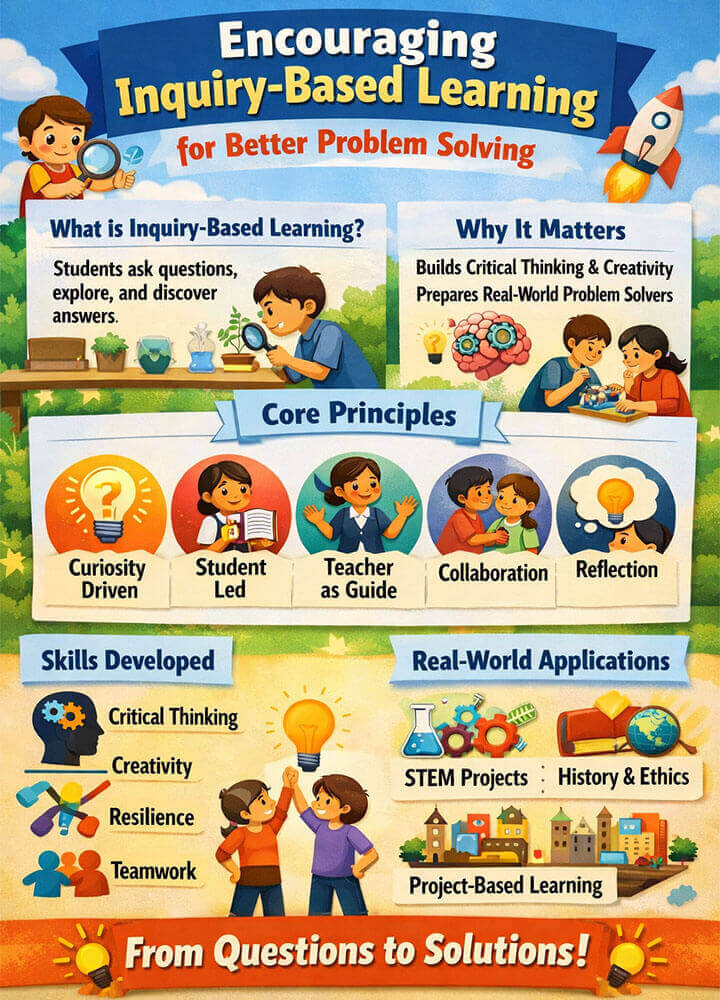

Encouraging Inquiry-Based Learning for Better Problem Solving:

If you have ever listened to a child endlessly asking questions (Why is the sky blue? How do ants find food? Why do we need sleep?); you have seen curiosity in its purest form. This natural desire to understand the world is not a distraction from learning; it is the foundation of it. Yet, in many traditional classrooms, curiosity is often sidelined in favor of rigid curricula, standardized testing, and memorization. As a result, students may perform well on exams but struggle to apply knowledge to real-life problems. Inquiry-based learning (IBL) offers a powerful alternative. Rooted in curiosity and active exploration, IBL encourages learners to ask questions, investigate problems, and construct knowledge through meaningful engagement. Research consistently shows that this approach enhances critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills; abilities that are increasingly essential in today’s complex and unpredictable world. In the rest of this article, we will explore encouraging Inquiry-Based Learning for better problem-solving, including its core principles, impact on problem-solving, and practical ways to implement it effectively.

What Is Inquiry-Based Learning?

Inquiry-based learning is a student-centered approach in which learning begins with questions rather than answers. Instead of passively receiving information from teachers, students actively explore concepts, investigate problems, and develop understanding through research, discussion, and reflection. Teachers act as facilitators who guide learners through the inquiry process rather than simply delivering content (Bell, Smetana, & Binns, 2005).

Educational theorists trace the roots of inquiry-based learning to constructivist philosophy, particularly the work of John Dewey, who argued that learning occurs most effectively through experience and reflection (Dewey, 1938). In an inquiry-based classroom, students behave like investigators (posing questions, examining evidence, testing ideas, and drawing conclusions) much like scientists, historians, or problem-solvers in real-world contexts.

Why Traditional Learning Often Falls Short:

Traditional learning models have long dominated formal education systems, relying heavily on teacher-centered instruction, standardized curricula, and summative assessments. While this approach has been effective for transmitting foundational knowledge to large groups of learners, extensive research suggests that it often falls short in developing deep understanding and real-world problem-solving skills.

One of the primary limitations of traditional learning is its emphasis on rote memorization rather than meaningful comprehension. Students are frequently encouraged to memorize facts, formulas, or definitions for examinations, with limited opportunities to apply this knowledge in authentic contexts. As a result, learning becomes superficial and short-lived, with information quickly forgotten once assessments are completed. Bransford, Brown, and Cocking (2000) argue that such approaches fail to support transfer of learning, meaning students struggle to apply what they have learned to new or unfamiliar problems.

Another significant shortcoming is the passive role assigned to learners. In conventional classrooms, teachers are positioned as the primary sources of knowledge, while students are expected to listen, take notes, and reproduce information. This “sage on the stage” model limits student engagement and discourages questioning, exploration, and independent thinking (Hmelo-Silver, Duncan, & Chinn, 2007). When learners are not actively involved in constructing knowledge, they are less likely to develop critical thinking and problem-solving abilities.

Traditional learning also tends to prioritize uniformity over individual thinking. Standardized curricula and assessments assume that all students learn in the same way and at the same pace. However, this approach often neglects students’ diverse interests, prior knowledge, and learning styles. Dewey (1938) criticized such rigid educational structures, emphasizing that learning disconnected from students’ experiences reduces motivation and limits intellectual growth.

Furthermore, conventional assessment methods (such as multiple-choice tests and timed examinations) are often poorly aligned with real-world problem solving. Real-life problems are rarely well-defined or solved through single correct answers. Instead, they require analysis, creativity, collaboration, and persistence. Prince and Felder (2006) note that traditional instruction may be efficient for content coverage, but it is less effective in cultivating higher-order thinking skills needed in professional and societal contexts.

Finally, traditional learning environments frequently discourage productive struggle and failure, both of which are essential for deep learning. Students may become overly focused on grades rather than understanding, leading to risk-avoidant behavior and fear of making mistakes. In contrast, research on metacognition and self-regulated learning highlights the importance of reflection, error analysis, and active engagement in developing robust learning strategies (Schraw, 1998; Zimmerman, 2002).

Thus, while traditional learning models can support knowledge transmission, they often fall short in preparing learners for complex, real-world problem-solving. Their focus on memorization, passive learning, standardized instruction, and limited assessment methods restricts the development of critical thinking, adaptability, and transferable skills. These limitations underscore the need for learner-centered approaches, such as inquiry-based learning, that better align with how people learn and solve problems in authentic contexts.

Core Principles of Inquiry-Based Learning:

IBL is grounded in constructivist learning theory, which holds that learners actively construct knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. The effectiveness of inquiry-based learning lies in a set of interrelated core principles that collectively foster deep understanding, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills.

1. Curiosity as the Starting Point: At the heart of inquiry-based learning is curiosity. Learning begins with meaningful questions that arise from students’ interests, prior knowledge, or real-world phenomena. Rather than presenting facts upfront, inquiry-based instruction invites learners to explore what they do not yet understand. Research shows that curiosity enhances attention, motivation, and long-term retention of knowledge, making it a powerful driver of learning (Engel, 2011). When students are encouraged to ask “why” and “how,” they become cognitively invested in the learning process, which leads to deeper conceptual understanding.

2. Student Ownership and Active Engagement: Inquiry-based learning places students at the center of the learning process. Learners take responsibility for defining questions, setting goals, gathering information, and drawing conclusions. This active involvement contrasts sharply with traditional models in which students are passive recipients of information. Bransford et al. (2000) emphasize that meaningful learning occurs when students actively engage with ideas and connect new information to prior knowledge. By owning their learning, students develop self-regulation, autonomy, and confidence; key attributes for effective problem solving (Zimmerman, 2002).

3. Teacher as Facilitator and Guide: In inquiry-based learning environments, the role of the teacher shifts from knowledge transmitter to facilitator or coach. Rather than providing direct answers, teachers scaffold learning by posing guiding questions, offering feedback, and helping students reflect on their thinking. This guided approach ensures that inquiry remains purposeful and cognitively demanding rather than unstructured or confusing. Hmelo-Silver, Duncan, and Chinn (2007) highlight that effective scaffolding is essential for supporting learners as they navigate complex problems and develop higher-order thinking skills.

4. Collaboration and Social Interaction: Inquiry-based learning is inherently social. Students often work in pairs or groups to explore questions, share ideas, and challenge one another’s assumptions. Through discussion and collaboration, learners are exposed to multiple perspectives, which helps refine reasoning and deepen understanding. This principle aligns with social constructivist theory, which emphasizes the role of interaction in cognitive development (Vygotsky, 1978). Collaborative inquiry also strengthens communication and teamwork skills that are vital for solving real-world problems.

5. Reflection and Metacognitive Awareness: A defining feature of inquiry-based learning is its emphasis on reflection. Students are encouraged not only to find solutions but also to think about how they approached a problem, what strategies were effective, and where they encountered difficulties. This metacognitive process enables learners to monitor and regulate their thinking, leading to improved learning outcomes over time (Schraw, 1998). Zimmerman (2002) further notes that reflective practices support self-regulated learning, allowing students to transfer problem-solving strategies across contexts.

6. Connection to Real-World Contexts: Inquiry-based learning emphasizes authenticity by situating learning within real-world problems and contexts. When students investigate issues that mirror real-life challenges, they are more likely to see the relevance of their learning and apply knowledge meaningfully. According to Prince and Felder (2006), learning environments that connect theory to practice are more effective in developing transferable problem-solving skills than traditional lecture-based instruction.

Therefore, the core principles of inquiry-based learning (curiosity-driven inquiry, student ownership, guided facilitation, collaboration, reflection, and real-world relevance) work together to create a rich learning environment. Supported by decades of educational research, these principles explain why inquiry-based learning is particularly effective in cultivating deep understanding and robust problem-solving abilities.

How Inquiry-Based Learning Enhances Problem-Solving Skills:

IBL strengthens problem-solving skills by actively engaging learners in the kinds of cognitive processes required to address complex, real-world challenges. Rather than presenting problems with predetermined solutions, inquiry-based learning immerses students in situations that require questioning, investigation, analysis, and reflection. This process aligns closely with how effective problem-solving occurs outside the classroom and is strongly supported by educational research.

1. Promotion of Critical Thinking and Analytical Reasoning: One of the most significant ways inquiry-based learning enhances problem-solving skills is by fostering critical thinking. Students are encouraged to examine evidence, evaluate sources, and question assumptions rather than accepting information at face value. Through inquiry, learners learn to break complex problems into manageable components and analyze relationships among variables. According to Bransford et al. (2000), problem solving improves when learners actively organize knowledge around key concepts rather than memorizing isolated facts. Inquiry-based learning supports this organization by requiring students to justify conclusions using evidence and logical reasoning.

2. Encouragement of Creative and Flexible Thinking: Real-world problems rarely have a single correct answer. Inquiry-based learning exposes students to open-ended questions that allow for multiple possible solutions, encouraging creativity and flexibility. By experimenting with different approaches and considering alternative explanations, students learn to think beyond conventional solutions. Prince and Felder (2006) note that inductive and inquiry-driven instructional methods are particularly effective in developing innovative thinking and adaptability; skills essential for solving ill-structured problems in professional and societal contexts.

2. Development of Persistence and Resilience: Problem-solving often involves uncertainty, false starts, and failure. Inquiry-based learning normalizes these experiences by positioning struggle as a natural and valuable part of learning. When students encounter obstacles during inquiry, they are encouraged to revise hypotheses, seek additional information, and refine strategies rather than abandon the task. Hmelo-Silver et al. (2007) emphasize that guided inquiry helps learners persist through cognitive challenges while maintaining productive engagement. Over time, this builds resilience and confidence in tackling complex problems.

3. Deepening of Conceptual Understanding: Inquiry-based learning promotes deeper understanding by requiring students to actively construct knowledge. Instead of memorizing procedures, learners explore underlying concepts and principles, which enables them to apply knowledge more effectively in new situations. Bransford et al. (2000) highlight that deep understanding is a critical factor in successful problem solving because it allows learners to recognize patterns and transfer learning across contexts. Inquiry-based experiences foster this depth by connecting new ideas to prior knowledge and real-world applications.

4. Strengthening of Metacognitive Skills: Effective problem solvers are aware of their own thinking processes. Inquiry-based learning explicitly supports metacognition by encouraging students to reflect on how they approach problems, monitor progress, and evaluate outcomes. Reflection activities (such as learning journals, group discussions, or self-assessment) help students identify effective strategies and areas for improvement. Research by Schraw (1998) and Zimmerman (2002) shows that metacognitive awareness and self-regulation significantly enhance problem-solving performance and long-term learning.

5. Enhancement of Collaborative Problem Solving: Many real-world problems require collaboration rather than individual effort. Inquiry-based learning frequently involves group investigations in which students share ideas, negotiate meaning, and collectively construct solutions. Through social interaction, learners are exposed to diverse perspectives that challenge assumptions and refine reasoning. This aligns with social constructivist principles emphasizing learning through interaction (Vygotsky, 1978). Collaborative inquiry not only improves problem-solving outcomes but also builds communication and teamwork skills essential in professional environments.

Consequently, inquiry-based learning enhances problem-solving skills by cultivating critical and creative thinking, resilience, deep understanding, metacognitive awareness, and collaborative competence. Supported by extensive research, this approach prepares learners to engage with complex, ill-structured problems more effectively than traditional instructional methods.

Real-Life Applications of Inquiry-Based Learning:

IBL is particularly valuable because it mirrors the way knowledge is used and problems are solved in real-world contexts. Outside the classroom, individuals rarely receive step-by-step instructions for addressing complex challenges. Instead, they must ask questions, gather information, evaluate evidence, collaborate with others, and reflect on outcomes. Inquiry-based learning prepares students for these realities by embedding learning within authentic tasks and practical situations.

- Application in STEM Education: In science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), inquiry-based learning closely aligns with professional practice. Scientists and engineers routinely formulate hypotheses, design experiments, analyze data, and revise conclusions based on evidence. Inquiry-based classrooms replicate this process by engaging students in activities such as investigating environmental issues, designing solutions to engineering problems, or testing scientific theories. The National Research Council (2000) emphasizes that inquiry is central to scientific literacy because it helps learners understand not only scientific concepts but also how scientific knowledge is generated. Through inquiry, students develop problem-solving skills that extend beyond the laboratory, including data interpretation, logical reasoning, and decision-making.

- Use in Social Studies and the Humanities: Inquiry-based learning is equally effective in social studies and humanities education. Rather than memorizing historical dates or political facts, students explore essential questions such as why social movements emerge, how power is distributed in societies, or how ethical dilemmas should be addressed. Through analyzing primary sources, debating interpretations, and constructing arguments, learners engage in authentic historical and civic inquiry. Dewey (1938) argued that education should be connected to lived experience, and inquiry-based approaches in the humanities support this connection by helping students apply analytical and ethical reasoning to contemporary social issues.

- Project-Based and Problem-Based Learning Contexts: Project-based and problem-based learning environments are among the most visible real-life applications of inquiry-based learning. In these settings, students work over extended periods to solve complex, real-world problems, such as developing a business plan, creating a sustainable community model, or addressing local environmental challenges. These projects require learners to integrate knowledge from multiple disciplines, collaborate with peers, and adapt strategies as new information emerges. Research indicates that such inquiry-driven projects promote deeper learning and stronger problem-solving abilities than traditional instruction (Hmelo-Silver, Duncan, & Chinn, 2007).

- Preparation for the Workplace and Professional Life: Inquiry-based learning also prepares students for modern workplaces, where employees are expected to think independently, solve novel problems, and collaborate effectively. Employers increasingly value skills such as critical thinking, adaptability, communication, and self-directed learning. Prince and Felder (2006) note that inquiry and inductive teaching methods better reflect professional practice than lecture-based instruction, as they engage learners in the same processes used by experts in the field. By practicing inquiry in educational settings, students develop transferable competencies essential for career success.

- Everyday and Lifelong Learning Applications: Beyond formal education, inquiry-based learning supports lifelong learning and informed decision-making. Whether evaluating health information, understanding social issues, or solving everyday problems, individuals rely on inquiry skills such as questioning sources, weighing evidence, and reflecting on outcomes. Bransford et al. (2000) emphasize that learning environments that promote inquiry help individuals become adaptive learners capable of applying knowledge across diverse contexts. These skills empower learners to navigate an increasingly complex world with confidence and responsibility.

So, the real-life applications of inquiry-based learning span academic disciplines, professional environments, and everyday life. By engaging learners in authentic problems that require investigation, collaboration, and reflection, inquiry-based learning bridges the gap between classroom knowledge and real-world problem solving. Supported by extensive research, this approach equips students with the skills necessary to address complex challenges in meaningful and sustainable ways.

Challenges and Strategies for Effective Implementation:

While IBL offers significant benefits for developing deep understanding and problem-solving skills, its implementation is not without challenges. Educators often face practical, institutional, and learner-related obstacles when shifting from traditional instructional models to inquiry-driven approaches. However, research suggests that these challenges can be effectively addressed through thoughtful planning, instructional scaffolding, and supportive learning environments.

- Time Constraints and Curriculum Coverage: One of the most frequently cited challenges of inquiry-based learning is the time it requires. Inquiry activities often take longer than traditional lectures because students need time to explore questions, conduct investigations, and reflect on their findings. In curriculum-driven educational systems, teachers may feel pressure to “cover” a large volume of content within limited instructional time. However, research indicates that depth of understanding is more valuable than superficial coverage of numerous topics. Bransford et al. (2000) argue that deep learning supports better transfer of knowledge, enabling students to apply what they learn more effectively in new contexts. To address time constraints, educators can design focused inquiry tasks aligned with core learning objectives and integrate inquiry gradually rather than attempting a complete instructional overhaul.

- Teacher Preparedness and Role Transition: Implementing inquiry-based learning requires teachers to adopt new roles as facilitators and guides, which can be challenging for educators trained in traditional teaching methods. Managing open-ended discussions, supporting diverse learning paths, and providing appropriate scaffolding demand strong pedagogical skills. Hmelo-Silver et al. (2007) emphasize that inquiry is most effective when teachers offer structured guidance that supports learners without removing cognitive responsibility. Professional development, peer collaboration, and reflective practice can help teachers build confidence and competence in facilitating inquiry-based instruction.

- Assessment and Evaluation Difficulties: Traditional assessment methods, such as standardized tests and multiple-choice exams, often fail to capture the complex learning outcomes associated with inquiry-based learning. Skills like critical thinking, collaboration, and metacognitive awareness are difficult to measure using conventional tools. Schraw (1998) and Zimmerman (2002) highlight the importance of reflective and self-regulatory processes in learning, suggesting that alternative assessments (such as portfolios, project presentations, learning journals, and self-assessments) are better suited to evaluating inquiry-based outcomes. While these methods require more time and effort, they provide richer insights into student learning and problem-solving development.

- Student Readiness and Cognitive Load: Not all students are immediately comfortable with open-ended learning environments. Learners accustomed to highly structured instruction may feel uncertain or overwhelmed when asked to generate questions and direct their own learning. Without proper support, inquiry-based tasks can impose excessive cognitive load. To mitigate this, teachers can scaffold inquiry by modeling questioning strategies, providing research frameworks, and gradually increasing learner autonomy. According to Bransford et al. (2000), scaffolding helps learners build conceptual understanding while maintaining engagement and confidence.

- Classroom Management and Collaboration Challenges: Inquiry-based learning often involves collaborative work, which can introduce challenges related to group dynamics, participation, and accountability. Unequal contribution or off-task behavior may hinder learning if not carefully managed. Drawing on social constructivist principles, educators can establish clear expectations, assign roles within groups, and encourage reflective discussion to promote productive collaboration (Vygotsky, 1978). Structured collaboration supports both individual accountability and shared problem solving.

- Aligning Inquiry with Real-World Relevance: Another challenge lies in designing inquiry tasks that are both curriculum-aligned and authentically connected to real-world contexts. Poorly designed inquiries may feel artificial or disconnected from learners’ experiences. Dewey (1938) emphasized that learning is most meaningful when connected to real-life situations. Educators can address this challenge by using real-world problems, case studies, and interdisciplinary projects that reflect issues students encounter beyond the classroom.

Therefore, while inquiry-based learning presents challenges related to time, assessment, teacher readiness, and student preparedness, these obstacles are not insurmountable. Research consistently shows that with appropriate scaffolding, reflective assessment practices, and professional support, inquiry-based learning can be implemented effectively and sustainably (Bransford et al., 2000; Hmelo-Silver et al., 2007). By addressing these challenges strategically, educators can create learning environments that foster curiosity, resilience, and powerful problem-solving skills.

In conclusion, inquiry-based learning represents a meaningful shift from memorization-driven education to learning rooted in curiosity, exploration, and understanding. By placing questions at the heart of instruction, this approach equips learners with the critical thinking, creativity, and resilience needed to solve complex problems in an ever-changing world. As global challenges become increasingly multifaceted, education must move beyond teaching students what to think and focus instead on teaching them how to think. Encouraging inquiry does more than improve academic outcomes; it nurtures lifelong learners who are capable of asking better questions, seeking evidence, and developing thoughtful solutions. When educators pause and embrace a student’s simple question (Why?); they open the door to deeper learning and more powerful problem-solving. Inquiry-based learning, therefore, is not just an instructional strategy; it is an investment in the thinkers and problem solvers of the future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

How is inquiry-based learning different from traditional teaching methods?

Traditional teaching often relies on lectures, memorization, and exams. Inquiry-based learning, on the other hand, emphasizes questioning, exploration, and applying knowledge to real situations. Students are actively involved in learning instead of passively receiving information.

Does inquiry-based learning work for all subjects?

Yes, Inquiry-based learning can be used across a wide range of subjects, including science, mathematics, social studies, humanities, and professional education. Any subject that encourages questioning, investigation, and critical thinking can benefit from this approach.

Is inquiry-based learning suitable for all students?

Inquiry-based learning can benefit all students, but the level of guidance may need to vary. Some learners may initially find open-ended tasks challenging. With proper support, structure, and gradual introduction, students develop confidence and independence over time.

What role does the teacher play in inquiry-based learning?

In inquiry-based learning, the teacher acts as a facilitator or coach rather than a lecturer. Teachers design meaningful learning experiences, ask guiding questions, provide feedback, and help students reflect, without giving all the answers directly.

How are students assessed in inquiry-based learning?

Assessment goes beyond traditional tests and quizzes. Common methods include projects, presentations, portfolios, reflective journals, and self-assessments. These methods help capture students’ thinking processes, problem-solving abilities, and overall learning growth.

Does inquiry-based learning take more time than traditional instruction?

Inquiry-based learning often takes more time, especially at the beginning. However, the deeper understanding and stronger problem-solving skills students gain usually make the time investment worthwhile, as learning becomes more meaningful and long-lasting.

How does inquiry-based learning support problem-solving skills?

Inquiry-based learning helps students develop problem-solving skills by encouraging them to analyze information, test ideas, learn from mistakes, and reflect on their strategies. These experiences closely resemble how problems are solved in real life.

Can inquiry-based learning be aligned with curriculum requirements?

Yes, Inquiry-based learning can be designed to meet curriculum goals by framing inquiry questions and projects around key learning objectives. It supports curriculum standards while allowing students to explore topics more deeply.

Why is inquiry-based learning important for the future?

The challenges of the modern world require critical thinkers, creative problem solvers, and adaptable learners. Inquiry-based learning prepares students with these skills by teaching them how to ask meaningful questions, seek solutions, and continue learning throughout their lives.

References:

- Bell, R. L., Smetana, L., & Binns, I. (2005). Simplifying inquiry instruction. The Science Teacher, 72(7), 30–33.

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan Company.

- Engel, S. (2011). Children’s need to know: Curiosity in schools. Harvard Educational Review, 81(4), 625–645. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.81.4.h054131316473115

- Facione, P. (2015). Critical Thinking: What It Is and Why It Counts. Insight Assessment.

- Hmelo-Silver, C. E., Duncan, R. G., & Chinn, C. A. (2007). Scaffolding and achievement in problem-based and inquiry learning: A response to Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006). Educational Psychologist, 42(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520701263368

- Krajcik, J., & Blumenfeld, P. (2006). 19. Project-Based Learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences (pp. 317-333). New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511816833.020

- National Research Council. (2000). Inquiry and the National Science Education Standards: A guide for teaching and learning. National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9596

- Prince, M. J., & Felder, R. M. (2006). Inductive Teaching and Learning Methods: Definitions, Comparisons, and Research Bases. Journal of Engineering Education, 95, 123-138. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2006.tb00884.x

- Schraw, G. (1998). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional Science, 26(1-2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003044231033

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory into Practice, 41, 64-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College