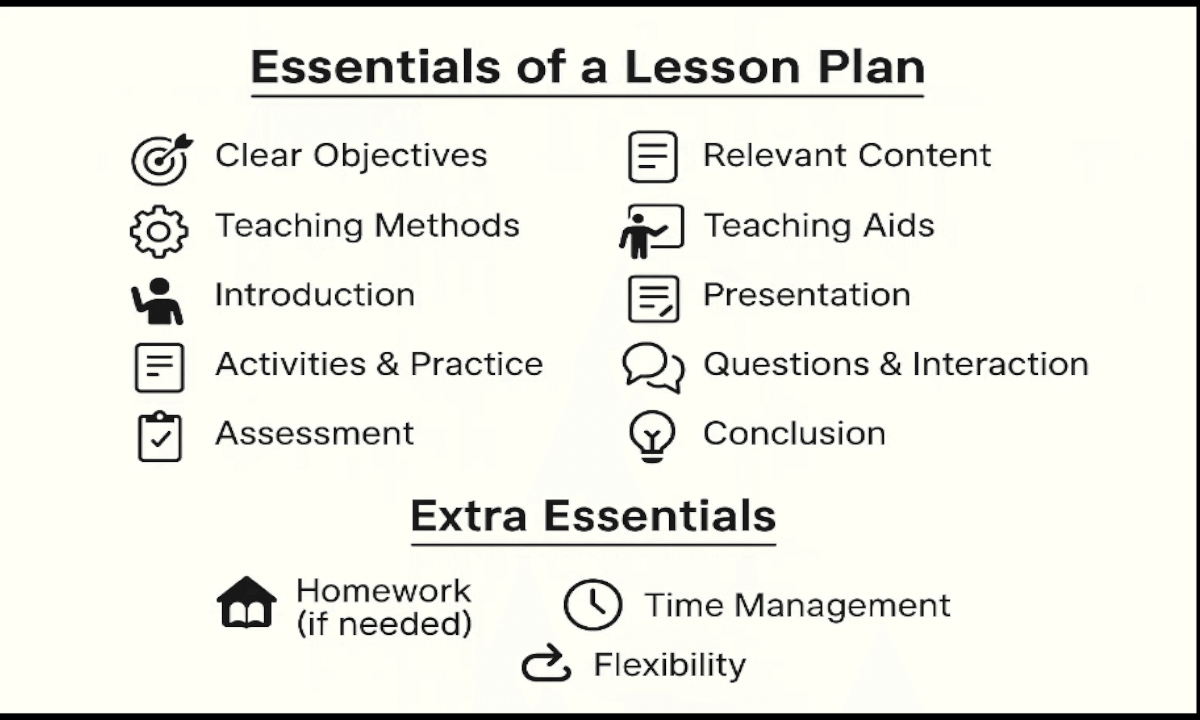

Essentials of a Lesson Plan:

Lesson planning is a fundamental aspect of effective teaching. It serves as a roadmap that guides teachers in delivering structured and purposeful instruction aligned with curriculum goals and learner needs (Richards & Bohlke, 2011). A well-crafted lesson plan ensures that teaching is not left to chance but is intentional, systematic, and responsive to students’ diverse learning styles (Burden & Byrd, 2019). In the rest of this article, we will explore the key essentials of a lesson plan that should be included to enhance student engagement and achievement.

For instance, an unclear objective like “Students will learn about fractions” leaves room for ambiguity. A clearer version would be: “Students will solve at least five problems involving addition and subtraction of fractions with unlike denominators.” This clarity helps teachers focus instruction and ensures students understand what is expected.

Clear objectives also guide the choice of teaching methods, materials, and assessment tools. Research shows that students perform better when they know what success looks like (Hattie, 2012). Therefore, teachers should always share objectives with students at the start of the lesson.

2. Relevant Content: Relevant and well-organized content is the backbone of a successful lesson. It connects directly to the set objectives and aligns with curriculum standards, ensuring that instruction is purposeful and meaningful (Orlich et al., 2013). Content should be pitched at an appropriate level of difficulty — challenging enough to stimulate thinking but not so difficult that it discourages learners (Bransford et al., 2000).

Teachers must also consider students’ prior knowledge. For example, when teaching about renewable energy, a teacher might first review basic concepts about energy sources before introducing solar and wind power. Real-life examples, local context, or current events can make content more engaging and relatable (Richards & Bohlke, 2011).

Additionally, teachers should adapt content to be culturally responsive and inclusive, reflecting students’ backgrounds and experiences to promote equity and belonging (Gay, 2018).

3. Teaching Methods: Selecting the right teaching methods is crucial for transforming objectives and content into meaningful learning experiences. The chosen method should match the lesson’s goals, the nature of the content, and students’ learning styles (Killen, 2016).

For example, direct instruction is effective for teaching factual information or procedures, like solving math problems. Cooperative learning is valuable for promoting collaboration and critical thinking, as in group projects or peer teaching (Johnson & Johnson, 2009). Inquiry-based learning suits topics where students investigate and discover concepts themselves, fostering curiosity and problem-solving skills.

Good teachers often blend methods within a single lesson. For instance, they may begin with a short lecture, then use a group activity, and finish with class discussion. Flexibility and variety ensure that students remain engaged and that diverse learners can connect with the material in ways that suit them best (Borich, 2016).

4. Teaching Aids: Teaching aids are vital tools that enrich the learning experience by making abstract concepts concrete and engaging multiple senses. According to Mayer’s (2009) Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, learners understand and retain information better when they process both verbal and visual materials. For instance, a science teacher explaining the structure of a cell might use diagrams, 3D models, or animations to help students visualize organelles that are otherwise invisible to the naked eye.

Effective teaching aids can be physical (charts, models, flashcards), digital (PowerPoint slides, videos, interactive whiteboards), or experiential (field trips, real specimens). They help clarify difficult ideas, save time, and hold students’ attention (Borich, 2016). When selecting aids, teachers must ensure they are age-appropriate, culturally sensitive, and directly related to the lesson’s objectives (Killen, 2016).

Moreover, using varied teaching aids supports different learning styles. Visual learners benefit from images and diagrams; auditory learners gain from videos and spoken explanations; kinesthetic learners learn better with manipulatives or experiments (Fleming & Baume, 2006).

5. Introduction: A well-planned introduction is critical because it sets the tone for the entire lesson. The introduction should grab students’ attention, connect to their prior knowledge, and make the purpose of the lesson clear (Orlich et al., 2013).

Effective strategies for introductions include:

- Asking a provocative question: “What would happen if there were no gravity?”

- Telling a short, relevant story.

- Showing an interesting object or visual.

- Using a surprising fact or statistic to spark curiosity.

Research shows that activating prior knowledge helps students integrate new information more effectively (Bransford et al., 2000). For example, before teaching about renewable energy, a teacher might ask students to list types of energy they already know or describe how their families use energy at home.

A clear introduction also outlines what students will learn and why it matters. This helps students see the relevance of the lesson, increasing motivation and engagement (Woolfolk Hoy, 2017).

6. Presentation: The presentation stage is the core of the lesson, where the teacher delivers new content step by step. Effective presentations are structured, logical, and interactive (Borich, 2016). Teachers should break complex material into manageable parts, provide clear explanations, and use examples that relate to students’ lives.

According to Rosenshine’s (2012) Principles of Instruction, good presentations include modeling, guided practice, and plenty of checks for understanding. For example, when teaching how to solve an algebra equation, a teacher might:

- Explain the concept step by step while solving an example on the board.

- Ask students to solve a similar problem in pairs.

- Discuss solutions as a class to address misconceptions.

Teachers should also vary their delivery to maintain interest — mixing explanations, visuals, stories, and brief discussions helps sustain attention (Orlich et al., 2013). Frequent questioning during the presentation allows teachers to gauge understanding and clarify misunderstandings in real time (Walsh & Sattes, 2017).

7. Activities & Practice: No lesson is complete without well-designed activities that allow students to practice and apply what they have learned. Practice consolidates understanding, develops skills, and builds confidence (Eggen & Kauchak, 2013).

Effective practice should follow the principle of guided to independent learning. First, students work under the teacher’s guidance with support; gradually, they practice on their own or in groups. For example, in a language lesson, students might first repeat new vocabulary with the teacher, then use it in dialogues with peers, and finally write sentences independently.

Activities should be varied and purposeful. They can include:

- Individual tasks (worksheets, writing exercises)

- Pair or group work (role-plays, projects)

- Hands-on tasks (science experiments, art projects)

- Games or simulations

Research shows that active learning strategies increase student engagement and deepen learning (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). Well-planned activities should always align with the lesson objectives, reinforce the key content, and accommodate different learning styles (Killen, 2016).

8. Questions & Interaction: High-quality questioning and interaction are core elements of effective teaching. They stimulate thinking, check understanding, and keep students involved (Walsh & Sattes, 2017).

Good lesson plans outline when and how to ask questions — not just at the end, but throughout the lesson. Teachers should balance lower-order (recall) and higher-order (analysis, synthesis, evaluation) questions (Bloom et al., 1956). For example:

- Recall: “What are the three states of matter?”

- Higher-order: “Why do you think ice floats on water?”

Effective teachers use wait time, giving students a few seconds to think before responding. This encourages deeper answers and gives all learners a chance to participate (Rowe, 1986).

Teachers can also plan interactive techniques like:

- Think-pair-share

- Group debates

- Peer teaching

- Socratic questioning

These approaches foster critical thinking and make students active participants rather than passive listeners (Walsh & Sattes, 2017).

9. Assessment: Assessment is essential for checking whether learning objectives have been achieved. It provides feedback to both teacher and students and guides the next steps in instruction (Popham, 2017).

A good lesson plan includes formative assessments, which happen during learning — such as quizzes, exit tickets, observation, or class discussions. For example, a quick mini-quiz at the end of a math lesson can show whether students understand fractions or need more practice.

Assessment should be valid (measures what it’s supposed to measure) and reliable (produces consistent results) (Nitko & Brookhart, 2014). It can also be summative, like a final test, but in daily lesson planning, formative checks are most useful to adapt teaching in real time.

Involving students in self-assessment or peer assessment helps them reflect on their progress and take responsibility for their learning (Black & Wiliam, 2009).

10. Conclusion: A strong conclusion is often underestimated, but it is crucial for wrapping up the lesson meaningfully and reinforcing what students have learned (Orlich et al., 2013). A good conclusion summarizes key points, checks if learning objectives have been met, and helps students reflect on new knowledge or skills (Borich, 2016).

For example, a teacher might review the main ideas on the board, ask students to explain a concept in their own words, or conduct a short quiz or reflection activity. This not only reinforces understanding but also provides the teacher with immediate feedback on what may need reteaching (Rosenshine, 2012).

Additionally, a clear conclusion should connect today’s lesson with what comes next. This helps students see the continuity of learning. For instance, a history teacher might say, “Today we learned about the causes of World War I. Next class, we’ll look at its major battles and impact on society.”

A purposeful ending leaves students with a sense of accomplishment and readiness for the next step.

11. Homework (If Needed): Homework can be a valuable extension of classroom learning when designed thoughtfully and used appropriately. It provides extra practice, reinforces concepts, and fosters independent study skills (Cooper, 2001).

However, research suggests that homework is most effective when it is meaningful, manageable, and clearly linked to the lesson objectives (Marzano & Pickering, 2007). For example, instead of repetitive worksheets, students might be asked to write a reflection, solve practical problems, or gather information from home or their community.

Homework should also consider students’ age and capacity — what works for high school may not suit young children (Cooper, 2001). It should come with clear instructions and deadlines, and ideally, teachers should discuss the homework’s purpose to motivate students.

12. Time Management: Time management is a critical but often overlooked part of lesson planning. A well-structured plan allocates appropriate time to each phase — introduction, presentation, activities, questions, and conclusion (Brown, 2007).

For instance, if a lesson is 45 minutes long, the teacher might plan:

- 5 minutes for introduction and motivation.

- 25 minutes for presentation and guided practice.

- 10 minutes for activities or discussion.

- 5 minutes for conclusion and wrap-up.

Effective time management ensures that the lesson stays on track and that all objectives are covered without rushing or dragging (Borich, 2016). It also gives teachers a buffer to address unexpected questions or deeper exploration when students show interest.

13. Flexibility: Even the best lesson plan should not be rigid. Effective teachers plan in detail but teach flexibly, adapting to students’ needs, unexpected challenges, or opportunities for deeper learning (Richards & Bohlke, 2011).

For example, if students struggle with a concept, the teacher might slow down, revisit the topic, or use a different method or aid. Alternatively, if students master a topic quickly, the teacher can extend the lesson with enrichment activities.

Flexibility ensures that instruction remains learner-centered, responsive, and dynamic — qualities essential for real classrooms (Tomlinson, 2014).

In conclusion, a thoughtfully prepared lesson plan is essential for effective teaching and successful learning outcomes. By integrating clear objectives, relevant content, appropriate methods, engaging materials, and interactive assessments, teachers create structured yet flexible learning experiences that meet diverse student needs (Killen, 2016). Ultimately, strong lesson planning empowers teachers to be confident facilitators of meaningful learning.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is the main purpose of a lesson plan?

A lesson plan serves as a structured roadmap for teachers. It ensures that teaching is intentional, objectives are clear, content is relevant, and that time is used effectively. It also helps teachers adapt their instruction to meet diverse learners’ needs.

How detailed should a lesson plan be?

A good lesson plan is detailed enough to guide teaching confidently but flexible enough to adapt. It should include objectives, content, methods, materials, activities, questions, assessment, and time allocations.

Do all teachers need to follow the same lesson plan format?

Not necessarily. While most formats share similar components, the design can vary depending on the teacher’s style, school policy, subject, and students’ age. The key is to cover the essentials: what to teach, how to teach it, and how to check learning.

How often should teachers write lesson plans?

Teachers often prepare daily lesson plans, but they may also plan by week, unit, or term. The frequency depends on the curriculum and context. Beginners usually benefit from detailed daily plans, while experienced teachers may work from outlines.

Why is flexibility important in lesson planning?

Flexibility lets teachers respond to students’ real-time needs, unexpected questions, or extra time needed to master a concept. Rigidly sticking to a plan without adjusting can hinder learning.

How can teachers keep students engaged throughout a lesson?

By using a variety of methods — questioning, group work, visuals, stories, and hands-on tasks — and by pacing the lesson well. Clear introductions and conclusions also help maintain focus and purpose.

What role do homework and practice play in a lesson plan?

Homework extends learning beyond the classroom and encourages independent study. Practice activities within the lesson help consolidate learning and build students’ confidence in applying new knowledge.

How does assessment fit into a single lesson plan?

Assessment is built into the lesson to check understanding continuously. This can be quick quizzes, exit tickets, discussions, or observations. Good formative assessment helps the teacher adjust instruction as needed.

What are some common mistakes in lesson planning?

Some common pitfalls include setting vague objectives, planning too much content for the time available, not including student interaction, or failing to prepare varied activities and teaching aids.

How can new teachers improve their lesson planning skills?

New teachers should practice writing clear objectives, observe experienced teachers, use lesson plan templates, and seek feedback. Over time, planning becomes more intuitive and efficient.

References:

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

- Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Longmans, Green.

- Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1). The George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development.

- Borich, G. D. (2016). Effective teaching methods: Research-based practice (9th ed.). Pearson.

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school (Expanded ed.). National Academy Press.

- Brown, H. D. (2007). Principles of language learning and teaching (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Cooper, H. (2001). The battle over homework: Common ground for administrators, teachers, and parents (2nd ed.). Corwin Press.

- Eggen, P., & Kauchak, D. (2013). Educational psychology: Windows on classrooms (9th ed.). Pearson.

- Fleming, N. D., & Baume, D. (2006). Learning styles again: VARKing up the right tree! Educational Developments, 7(4), 4–7. http://www.johnsilverio.com/EDUI6702/Fleming_VARK_learningstyles.pdf

- Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Routledge.

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2009). An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educational Researcher, 38(5), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09339057

- Killen, R. (2016). Effective teaching strategies: Lessons from research and practice (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Marzano, R. J., & Pickering, D. J. (2007). The case for and against homework. Educational Leadership, 64(6), 74–79.

- Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Moss, C. M., & Brookhart, S. M. (2012). Learning targets: Helping students aim for understanding and ownership of learning. ASCD.

- Nitko, A. J., & Brookhart, S. M. (2014). Educational assessment of students (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Orlich, D. C., Harder, R. J., Callahan, R. C., Trevisan, M. S., & Brown, A. H. (2013). Teaching strategies: A guide to effective instruction (10th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Popham, W. J. (2017). Classroom assessment: What teachers need to know (8th ed.). Pearson.

- Richards, J. C., & Bohlke, D. (2011). Creating effective language lessons. Cambridge University Press.

- Rosenshine, B. (2012). Principles of instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator, 36(1), 12–19.

- Rowe, M. B. (1986). Wait time: Slowing down may be a way of speeding up! Journal of Teacher Education, 37(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718603700110

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). ASCD.

- Walsh, J. A., & Sattes, B. D. (2017). Questioning for classroom discussion: Purposeful speaking, engaged listening, deep thinking. ASCD.

- Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2017). Educational psychology (13th ed.). Pearson.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College