Formulating a Research Problem

Research is a methodical strategy to discover information that you and other people did not know, which is generally known as research problems. Considering that research is problem-driven, the first step in starting a study is to identify and choose the issue to be studied. Identifying a research problem is essential because, as the issue or concern in a particular setting motivates and guides the need for conducting a study, it lays the foundation for an entire project. If the foundation is shaky the entire project is doomed to failure. This is why novice researchers necessitate absolute caution in the initial stages of a research project. Professional researchers could easily identify a research problem because they have been quite familiar with the phenomena in which a problem generally presents itself. By considering the phenomena which include (1) a difficulty or deficiency to be overcome; (2) a condition to be improved upon; (3) a gap in knowledge that exists in scholarly literature that is to be filled; (4) a theory that requires meaningful understanding; or (5) a body of knowledge or views held in a different clime that requires validation or confirmation for local application, professional researchers could easily recognize the suitable problem to study. In the rest of this article, we are going to present to you the importance of formulating a research problem, sources of research problems, considerations in selecting a research problem, steps in formulating a research problem, and how to formulate research objectives.

The Research Problem

Broadly speaking, any question that we want to be answered and any assumption or assertion that we want to challenge or investigate can become a research problem or a research topic for a study. However, not all questions can be transformed into research problems and some may prove to be extremely difficult to study.

“Research problem, in general, refers to some difficulty which a researcher experience in the context of either a practical or theoretical situation and want to obtain the solution for the same” (C. R Kothari)

‘Potential research questions may occur to us on a regular basis, but the process of formulating them in a meaningful way is not at all an easy task.’ (Powers, Meenaghan and Twoomey -1985)

It might seem very easy to formulate a research problem but it requires considerable knowledge of both the subject area and research methodology. Once we examine a question more closely, we will soon realize the complexity of formulating an idea into a problem that is researchable. It is essential for the problem we formulate to be able to withstand scrutiny in terms of the procedures required to be undertaken. Hence, we should spend considerable time thinking it through.

Importance of Formulating Research Problem

Formulation of a research problem is the first and most important step of the research process and it is like the identification of a destination before undertaking a journey. In absence of a destination, it is impossible to identify the shortest – or indeed any – route. Similarly, in absence of a clear research problem – a clear and economical plan of study is impossible.

In other words, a research problem is like the foundation of a building. The type and design of the building are dependent upon the foundation. If the foundation is well-designed and strong, we can expect the building to be so.

A research problem serves as the foundation of a research study: if it is well formulated, we can expect a good study to follow.

“If one wants to solve a problem, one must generally know what the problem is. It can be said that a large part of the problem lies in knowing what one is trying to do.” (Kerlinger-1986)

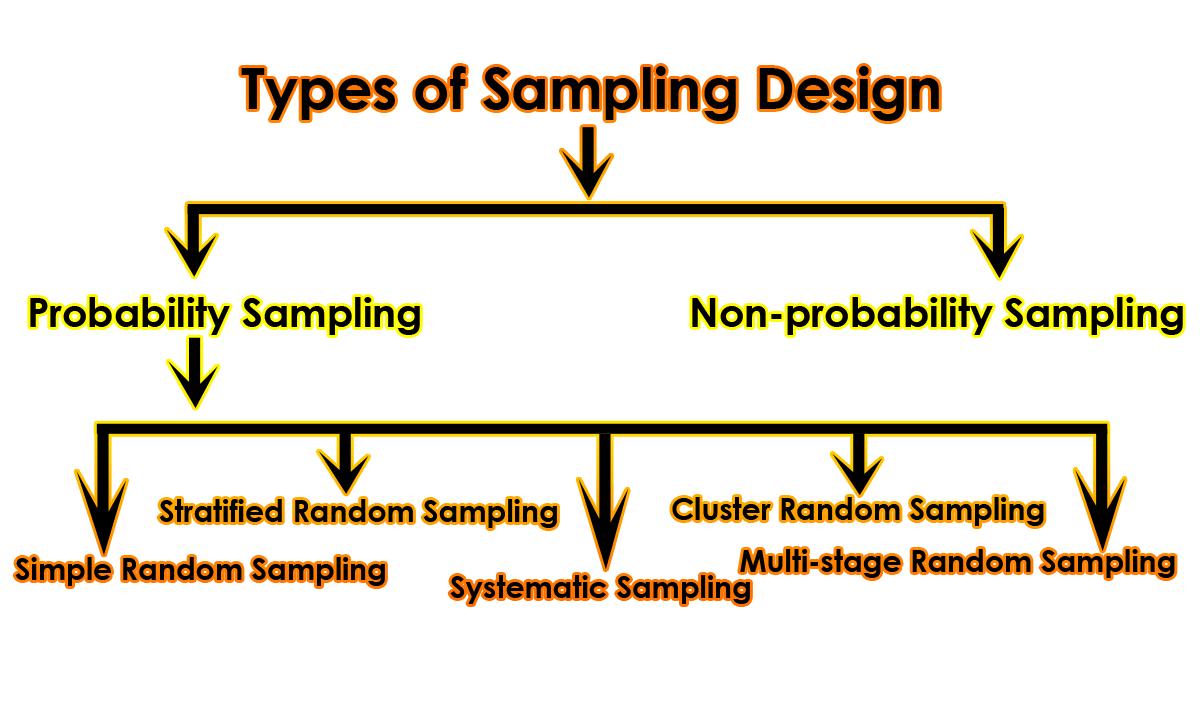

A research problem may take a number of forms, from very simple to very complex one. The way we formulate a problem determines almost every step that follows:

- The type of study design that can be used;

- The type of sampling strategy that can be employed;

- The research instrument that can be used or developed; and

- The type of analysis that can be undertaken.

Suppose your broad area of interest is Depression. Further, suppose you want to conduct a research study regarding services available to patients living in a community.

If the focus is to find out the types of service available to the patients, the study will dominantly be descriptive and qualitative. These types of studies fall in the category of qualitative research and are carried out using qualitative research methodologies.

Alternatively, if you want to find out the extent of use of the services, that is the number of people using them, it will dominantly use quantitative methodologies even though it is descriptive in nature in describing the number of people using a service. Again, if your focus is to determine the extent of use in relation to the personal attributes of the patients, the study will be classified as correlational (and quantitative). Similarly, if your aim is to find out the effectiveness of these services, the study will be classified as correlational and therefore the study design used, methods of collecting data, and its analysis will be a part of the quantitative methodology.

Hence, the way you formulate a research problem determines all the subsequent steps that you have to follow during a research journey.

Formulation of a research problem is like the ‘input’ to a study, and the ‘output’ i.e., the quality of the contents of the research report and the validity of the associations or causation established – is entirely dependent upon it. The famous saying about computers, -‘ garbage in, garbage out ‘; is equally applicable to formulating a research problem.

Initially, you may become more confused but this is a normal phenomenon and a sign of progression. Because confusion is often but the first step towards clarity! You should take time over formulating a research problem, for the clearer you are about your research problem/question, the easier it will be for you in later stages. This is considered to be the most crucial step in conducting research.

Sources of Research Problems

This is of particular relevance if you have not yet selected a research topic and do not know where to start. Most research in the humanities revolves around 4Ps: People; Problems; Programs; and Phenomena. A closer look at any field will show that most research studies revolve around these 4Ps. The emphasis on a particular ‘P’ may, however, vary from study to study but generally, in practice, most research studies are based upon at least a combination of two Ps. You may select a group of individuals (‘people’) to examine the existence of certain issues or problems relating to their lives, to ascertain their attitude towards the issue (‘problem’), to establish the existence of a regularity (‘phenomenon’) or to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention (‘program’).

Your focus may also be the study of an issue, an association or a phenomenon per se e.g., the relationship between unemployment and street crime, smoking and cancer, or fertility and mortality, which is done on the basis of information collected from individuals, groups, communities, or organizations. The emphasis here is on exploring, discovering, or establishing associations or causation. Similarly, we can study different aspects of a program: its effectiveness, its structure, the need for it, consumers’ satisfaction with it, and so on. In order to ascertain these, we collect information from people.

Every study has two aspects: the people provide us with the ‘Study Population’, whereas the other three Ps furnish the ‘Subject Areas’. Study Population: individuals, groups, and communities – the people from whom the information is collected. Subject Area: a problem, program, or phenomenon about which the information is collected.

You can study a problem, a program, or a phenomenon in any academic field or from any professional perspective. For example, you can measure the effectiveness of a program in the field of health, education, social work, industrial management, public health, nursing, health promotion, or welfare, or you can look at a problem from health, business, or welfare perspective.

Similarly, you can gauge consumers’ opinions about any aspect of a program in the above fields. For example, if you are a student in the health field there are an enormous number of issues, situations, and associations within each subfield of health that you could examine.

Issues relating to the spread of a disease, drug rehabilitation, an immunization program, the effectiveness of a treatment, the extent of consumers’ satisfaction, or issues concerning a particular health program can all provide you with a range of research problems. Correspondingly, in education, there are several issues: students’ satisfaction with a teacher, attributes of a good teacher, the impact of the home environment on the educational achievement of students, and the supervisory needs of postgraduate students in higher education, etc. Any other academic or occupational field can similarly be dissected into subfields and examined for a potential research problem.

Most fields lend themselves to the above categorization even though specific problems and programs will vary markedly from field to field. The concept of 4Ps is applicable to both quantitative and qualitative research though the main difference at this stage is the extent of their specificity, dissection, precision, and focus. In qualitative research, these attributes are deliberately kept very loose so that you can explore more as you go along, in case you find something of relevance.

Considerations in Selecting a Research Problem

In selecting a research problem/topic there are a number of considerations to keep in mind which will help to ensure that a study will be manageable and that you remain motivated. The considerations are:

- Interest: Interest should be the most important consideration in selecting a research problem. A research endeavor is usually time-consuming and involves hard work and possibly unforeseen problems. If you select a topic that does not greatly interest you, it could become extremely difficult to sustain the required motivation and put in enough time and energy to complete it.

- Magnitude: You should have sufficient knowledge about the research process to be able to visualize the work involved in completing the proposed study. Narrow the topic down to something manageable, specific, and clear. It is extremely important to select a topic that you can manage within the time and with the resources at your disposal. Even if you are undertaking a descriptive study, you need to consider its magnitude carefully.

- Measurement of Concepts: If you are using a concept in your study (in quantitative studies), make sure that you are clear about its indicators and their measurement. For example, if you plan to measure the effectiveness of a health promotion program, you must be clear as to what determines the effectiveness and how it will be measured. You should not use concepts in a research problem that you are not sure how to measure it. This does not mean that you cannot develop a measurement procedure as the study progresses.

- Level of Expertise: Make sure that you have an adequate level of expertise for the task you are proposing. Allow for the fact that you will learn during the study and may receive help from your research supervisor and others, but remember that you need to do most of the work yourself.

- Relevance: Select a topic that is of relevance to you as a professional. Ensure that a study adds to the existing body of knowledge, bridges current gaps, or is useful in policy formulation. This will help you to sustain your interest in the study.

- Availability of Data: If any topic entails the collection of information from secondary sources (office records, client records, census or other already-published reports, etc.) make sure that this data is available and in the format you want before finalizing a topic.

- Ethical Issues: Another important consideration in formulating a research problem is the ethical issues involved. In course of a research study, the study population may be adversely affected by some of the questions (directly or indirectly); deprived of an intervention; expected to share sensitive and private information, or expected to be simply experimental ‘guinea pigs’. How ethical issues can affect the study population and how ethical problems can be overcome should be thoroughly examined at the problem-formulation stage.

Steps in Formulating a Research Problem

Formulation of a research problem is the most crucial part of the research journey as the quality and relevance of a research project entirely depend upon it. Every step that constitutes the ‘How’ part of the research journey depends upon the way you formulated your research problem. The process of formulating a research problem consists of a number of steps. Working through these steps presupposes a reasonable level of knowledge of the broad subject area within which the study is to be undertaken and the research methodology itself. A brief review of the relevant literature helps in broadening this knowledge base. Without such knowledge, it is difficult to ‘dissect’ a subject area clearly and adequately. If you do not know what specific research topics, ideas, questions, or issues you want to research, first go through the following steps:

Step 1: Identify a broad field or subject area of interest. Ask yourself, ‘What is it that really interests you as a professional?’ This will help you to find an interesting topic and one which may be of use to you in the future. For example, if you are a social work student, inclined to work in the area of youth welfare, refugees, or domestic violence after graduation, you might take to research in one of these areas. Or if you are studying marketing you might be interested in researching consumer behavior. Or, as a student of public health, intending to work with patients who have HIV/AIDS, you might like to conduct research on a subject area relating to HIV/AIDS.

Step 2: Dissecting the broad area into subareas. At the onset, you should realize that all the broad areas– youth welfare, refugees, domestic violence, consumer behavior, and HIV/AIDS – have many aspects. For example, there are many aspects and issues in the area of domestic violence. Similarly, you can select any subject area from other fields such as community health or consumer research, and go through this dissection process. In preparing the list of subareas, you should also consult others who have knowledge of the area and the literature in the subject area. Once you have developed an exhaustive list of the subareas from various sources, you proceed to the next stage where you select what will become the basis of an inquiry.

Step 3: Select what is of most interest to you. It is neither advisable nor feasible to study all subareas. Select the issues with which you are passionate. Because your interest should be the most important determinant for selection. One way to decide what interests you most is to start with the process of elimination. Go through the list and delete all those subareas in which you are not very interested. Towards the end of this process, it will become very difficult for you to delete anything further. You need to continue until you are left with something that is manageable considering the time available, your level of expertise, and other resources needed to undertake the study. Once you are confident that you have selected an issue you are passionate about and can manage, you are ready to go to the next step.

Step 4: Raise Research Questions. At this step ask yourself, ‘What is it that I want to find out about in this subarea?’ Make a list of whatever questions come to your mind relating to your chosen subarea and if you think there are too many to be manageable, go through the process of elimination, as you did in Step 3.

Step 5: Formulate Objectives. Both your main objectives and your sub-objectives now need to be formulated, which grow out of your research questions. The main difference between objectives and research questions is the way in which they are written. Research questions are obviously that – questions. Objectives transform these questions into behavioral aims by using action-oriented words such as ‘to find out’, ‘to determine’, ‘to ascertain’, or ‘to examine’ etc. Some researchers prefer to reverse the process; that is, they start from objectives and formulate research questions from them. Some researchers are satisfied only with research questions and do not formulate objectives at all. If you prefer to have only research questions or only objectives, this is fine, but keep in mind the requirements of your institution for research proposals.

Step 6: Assess Your Objectives. Now examine your objectives to ascertain the feasibility of achieving them through your research endeavor. Consider them in light of the time, resources (financial and human), and technical expertise you have.

Step 7: Double-check. Go back and give final consideration to review whether or not you are sufficiently interested in the study, and have adequate resources to undertake it. Ask yourself, ‘Am I really enthusiastic about this study?’ and ‘Do I really have enough resources to undertake it?’ Answer these questions thoughtfully and realistically. If your answer to one of them is ‘No’, reassess your objectives.

Formulation of Research Objectives

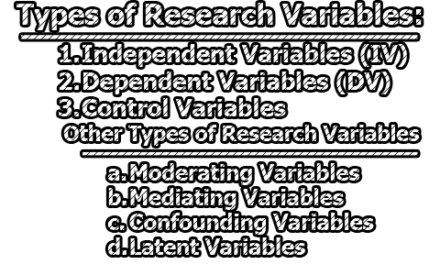

Research objectives are the goals you set out to attain in your study. Since these objectives inform a reader of what you want to achieve through the study, it is extremely important to word them clearly and specifically. Objectives should be listed under two headings: Main Objectives and Sub Objectives.

The main objective is an overall statement of the thrust of a study. It is also a statement of the main associations and relationships that you seek to discover or establish.

The sub-objectives are the specific aspects of the topic that you want to investigate within the main framework of your study. Sub-objectives should be numerically listed. They should be worded clearly and unambiguously. Make sure that each sub-objective contains only one aspect of the study. Use action-oriented words or verbs in writing your objectives.

The objectives should start with words such as ‘to determine, ‘to find out’, ‘to ascertain’, ‘to measure’ or ‘to explore’ etc.

The way the main objectives and sub-objectives are worded determines how your research is classified (e.g. descriptive, correlational, or experimental). In other words, the wording of your objectives determines the type of research design you need to adopt. Hence, you should be careful about the way you word your objectives. Irrespective of the type of research, the objectives should be expressed in such a way that the wording clearly, completely, and specifically communicates to your readers your intention. There is no place for ambiguity, non-specificity, or incompleteness, either in the wording of your objectives or in the ideas they communicate.

At the end of the day, we can say that it is important to have a proper understanding of the process and steps involved in the formulation of the research problem. Careful consideration of this phase is essential for strengthening the validity of one’s research work. The researcher is obliged and committed to evaluating the effectiveness of the research problem in selecting; stating and defining the problem as it largely impacts related procedures in the process of research. The researcher must be aware of the paradigm adapted for the study in time of working on the statement problem. Other related factors like duration of the study, availability of resources, manageability, the convenience of the study, etc.; are also need to consider at the phase of stating and defining the problem.

References:

- Pardede, Parlindungan. (2018). Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem.

- Sivakumar, S. & Szalinski, C. (2016). How to choose a research area. https://www.ascb.org/compass/compass-points/choose-research-area/

- Ratan SK, Anand T, Ratan J. Formulation of Research Question – Stepwise Approach. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2019 Jan-Mar;24(1):15-20. doi: 10.4103/jiaps.JIAPS_76_18. PMID: 30686882; PMCID: PMC6322175.

- https://egyankosh.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/41939/1/Unit-4.pdf

- https://www.slideshare.net/girish_bms/formulating-a-research-problem-research-methodology

- R. Kothari, Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques (New Delhi: New Age InternationalPublishers, 2010), 24.

- Mabry, Hunter P. A Manual for Researchers and Writers. 2nd ed. Bangalore: BTESSC, 1999.

- Mangal, S. K and Shubra Mangal. Research Methodology in Behavioural Sciences. New Delhi: PHI Learning Private Ltd., 2015.

- Ahuja, Ram. Research Methods. Jaipur: Rawat Publications, 2001.

- Walliman, Nicholas. Research Methods: The Basics. London: Routledge, 2011.

Assistant Teacher at Zinzira Pir Mohammad Pilot School and College