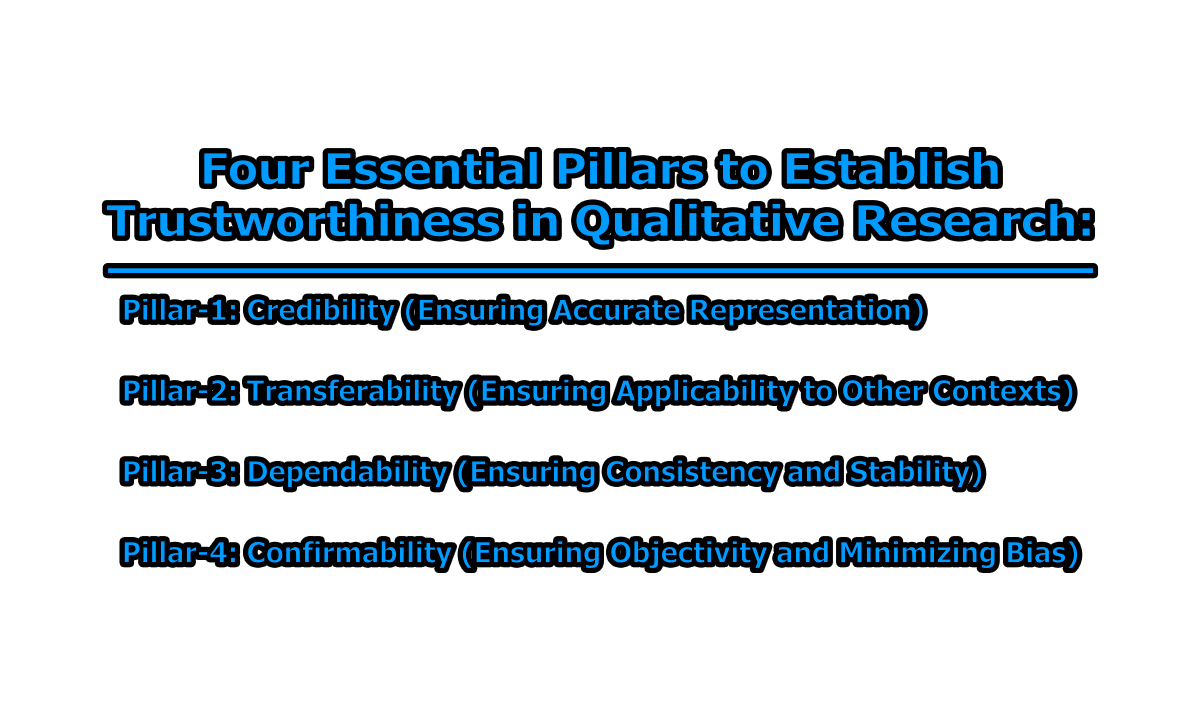

Four Essential Pillars to Establish Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research:

In qualitative research, trustworthiness is a fundamental criterion that determines the credibility, reliability, and applicability of a study. Trustworthiness ensures that qualitative research findings are meaningful and accurately represent participants’ lived experiences. Unlike quantitative research, where validity and reliability are paramount, qualitative research emphasizes the authenticity and richness of human experiences. To establish trustworthiness, researchers rely on four essential pillars: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). This article explores four essential pillars to establish trustworthiness in qualitative research, providing strategies for implementation and real-world examples to guide researchers in enhancing the rigor of their qualitative studies.

Understanding Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research:

Trustworthiness in qualitative research refers to the degree to which research findings can be considered accurate, applicable, and unbiased. It ensures that the study’s conclusions genuinely reflect the participants’ experiences rather than being shaped by the researcher’s preconceptions. Given that qualitative research often deals with subjective and interpretive data, establishing trustworthiness is crucial in validating the study’s findings (Shenton, 2004).

Guba and Lincoln (1989) proposed the concept of trustworthiness as an alternative to the positivist criteria of validity and reliability used in quantitative research. They introduced the four key criteria—credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability—to assess the quality of qualitative research. Each of these elements plays a critical role in strengthening the research process and ensuring that the findings are meaningful and replicable.

Pillar-1: Credibility (Ensuring Accurate Representation):

Credibility in qualitative research refers to the degree to which the research findings reflect participants’ actual experiences. It is comparable to internal validity in quantitative research and focuses on whether the study accurately captures what it claims to investigate (Patton, 2015).

Strategies to Enhance Credibility:

- Prolonged Engagement: Spending extended time with participants helps researchers develop deeper insights into their experiences. This technique allows researchers to build trust and obtain richer data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

- Member Checking: Researchers should share their interpretations and findings with participants to verify accuracy. This process ensures that the participants’ voices are correctly represented and helps identify any misinterpretations (Birt et al., 2016).

- Triangulation: Using multiple data sources, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, strengthens credibility by cross-validating findings (Denzin, 2012).

- Peer Debriefing: Engaging colleagues or external experts to review the research process helps uncover potential biases and enhances credibility (Creswell & Poth, 2017).

- Persistent Observation: Researchers should continuously observe and analyze participant behaviors and interactions to ensure the accuracy and depth of their findings. This helps in identifying patterns that might otherwise be overlooked (Korstjens & Moser, 2018).

- Reflexivity Practices: Researchers should engage in continuous self-reflection to acknowledge and minimize personal biases that could affect data interpretation (Berger, 2015).

- Negative Case Analysis: Identifying and examining cases that contradict the dominant findings ensures that different perspectives are considered, increasing the credibility of the study (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014).

- Use of Thick Descriptions: Providing detailed narratives and contextual descriptions enables readers to understand the depth and authenticity of the findings (Geertz, 1973).

- Expert Validation: Consulting subject matter experts for feedback on interpretations can help ensure that the findings align with established knowledge and perspectives in the field (Creswell, 2013).

Example (Enhancing Credibility): Imagine a researcher conducting a study on remote workers’ experiences. To enhance credibility:

- They engage with participants over several months to fully understand their daily challenges.

- They conduct member checking by sharing their findings with participants for feedback.

- They triangulate data by combining interviews, survey responses, and workplace observations.

- They employ persistent observation to refine their understanding of recurring challenges faced by remote workers.

- They apply negative case analysis by considering workers who have had significantly different experiences and incorporating their insights into the findings.

Pillar-2: Transferability (Ensuring Applicability to Other Contexts):

Transferability refers to the extent to which qualitative research findings can be applied to other contexts or settings. Unlike quantitative research, which seeks generalizability, qualitative research emphasizes providing rich, detailed descriptions to allow others to determine the applicability of findings (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Strategies to Enhance Transferability:

- Thick Description: Providing in-depth descriptions of the research context, participants, and setting enables others to assess whether findings are applicable to their situation (Geertz, 1973).

- Detailed Methodology Reporting: Clearly outlining the research methods, sampling strategy, and contextual factors allows future researchers to replicate or compare findings (Tracy, 2010).

- Contextual Variation Analysis: By analyzing differences and similarities between study settings, researchers can enhance the potential applicability of their findings to diverse contexts (Shenton, 2004).

- Multiple Case Comparisons: Comparing findings across multiple cases or groups enhances the understanding of broader applicability beyond a single setting (Yin, 2018).

- Use of Purposive Sampling: Selecting participants with diverse backgrounds ensures that multiple perspectives are included, increasing the relevance of findings to various contexts (Palinkas et al., 2015).

Example (Enhancing Transferability): Consider a study on how nurses cope during a hospital crisis. To ensure transferability:

- The researcher provides a comprehensive description of the hospital environment, crisis conditions, and nurse demographics.

- The detailed contextual information allows others to determine whether the findings apply to their own hospital setting.

- The researcher includes an analysis of how different hospital settings may influence nurses’ coping mechanisms, ensuring a broader applicability of the findings.

- The study includes multiple hospitals to provide a comparative analysis and strengthen its applicability across different settings.

- The researcher uses purposive sampling to include nurses with diverse professional backgrounds and levels of experience.

Pillar-3: Dependability (Ensuring Consistency and Stability):

Dependability refers to the stability and consistency of qualitative research findings over time. It ensures that if the study were repeated under similar conditions, the results would be comparable. To achieve dependability, researchers must maintain methodological rigor and transparency throughout the research process.

Strategies to Enhance Dependability:

- Maintaining an Audit Trail: A detailed record of research decisions, data collection methods, coding strategies, and data interpretation helps establish a clear pathway for others to follow. This documentation allows for an external review and validation of the research process (Nowell et al., 2017).

- Engaging in Reflexivity: Researchers should consistently reflect on their biases, assumptions, and role in the research process. By maintaining a reflexive journal, they can document personal thoughts and decisions that may influence data interpretation (Berger, 2015).

- Using Code-Recode Strategies: Reanalyzing the data at different points during the research process ensures consistency in coding and interpretation. This involves coding a portion of the data, taking a break, and then returning to recode the same data to check for consistency (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014).

- Conducting External Audits: Having an independent reviewer examine the research process helps identify inconsistencies and confirm that findings align with the data collected. External audits contribute to the reliability of the research (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

- Ensuring Methodological Coherence: The research design, data collection, and analysis should align with the research questions and theoretical framework. Any deviations should be justified and documented to maintain a coherent methodological approach (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Example (Enhancing Dependability) Consider a study examining the impact of social media on youth self-esteem. To ensure dependability:

- The researcher maintains detailed notes on the interview process, coding framework, and decision-making steps.

- A reflexive journal is kept to document potential biases and their impact on data interpretation.

- Data coding is conducted in multiple rounds, with checks for consistency.

- An external reviewer is invited to audit the study to confirm methodological transparency.

- The study design remains aligned with the research objectives, ensuring coherence across all stages.

Pillar-4: Confirmability (Ensuring Objectivity and Minimizing Bias):

Confirmability focuses on ensuring that the research findings are based on participants’ responses rather than researcher biases or subjective interpretations. This criterion aligns with the concept of objectivity in quantitative research.

Strategies to Enhance Confirmability:

- Establishing an Audit Trail: Keeping comprehensive records of all research decisions, raw data, coding procedures, and analytic steps allows others to trace how conclusions were derived (Nowell et al., 2017).

- Practicing Reflexivity: Researchers should engage in self-examination to recognize personal biases and how they may affect data collection and analysis. Writing reflexive memos can help document these reflections and ensure transparency (Berger, 2015).

- Using Triangulation: Incorporating multiple data sources, such as interviews, focus groups, and document analysis, ensures that findings are well-supported and not reliant on a single perspective (Denzin, 2012).

- Engaging in Peer Debriefing: Discussing the research process with colleagues or subject matter experts allows for an external critique of potential biases and enhances the neutrality of findings (Creswell & Poth, 2017).

- Providing Transparent Documentation: Clearly detailing how data were collected, analyzed, and interpreted enables others to assess the credibility of the findings and verify the neutrality of conclusions (Shenton, 2004).

Example (Enhancing Confirmability): Imagine a researcher studying voter behavior in a particular region. To ensure confirmability:

- The researcher maintains an audit trail documenting data sources, coding decisions, and thematic analysis.

- A reflexive journal is used to record personal biases and strategies for mitigating them.

- Data triangulation is applied by comparing interview data with survey results and secondary sources.

- Peer debriefing is conducted to validate findings and uncover potential biases.

- Transparent reporting ensures that all interpretations are directly linked to the data.

It is apparent that trustworthiness in qualitative research ensures that findings are credible, applicable, consistent, and objective. By focusing on the four key pillars—credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability—researchers can enhance the rigor and reliability of their studies. Implementing strategies such as prolonged engagement, member checking, thick description, audit trails, and reflexivity strengthens qualitative research and ensures that findings genuinely reflect participants’ experiences. By prioritizing trustworthiness, researchers contribute valuable and reliable knowledge to their respective fields.

References:

- Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219-234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

- Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1802-1811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Denzin, N. K. (2012). Triangulation 2.0. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(2), 80-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689812437186

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. Basic Books.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. SAGE Publications.

- Korstjens, I., & Moser, A. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 120-124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Publications.

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533-544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63-75. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837-851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College