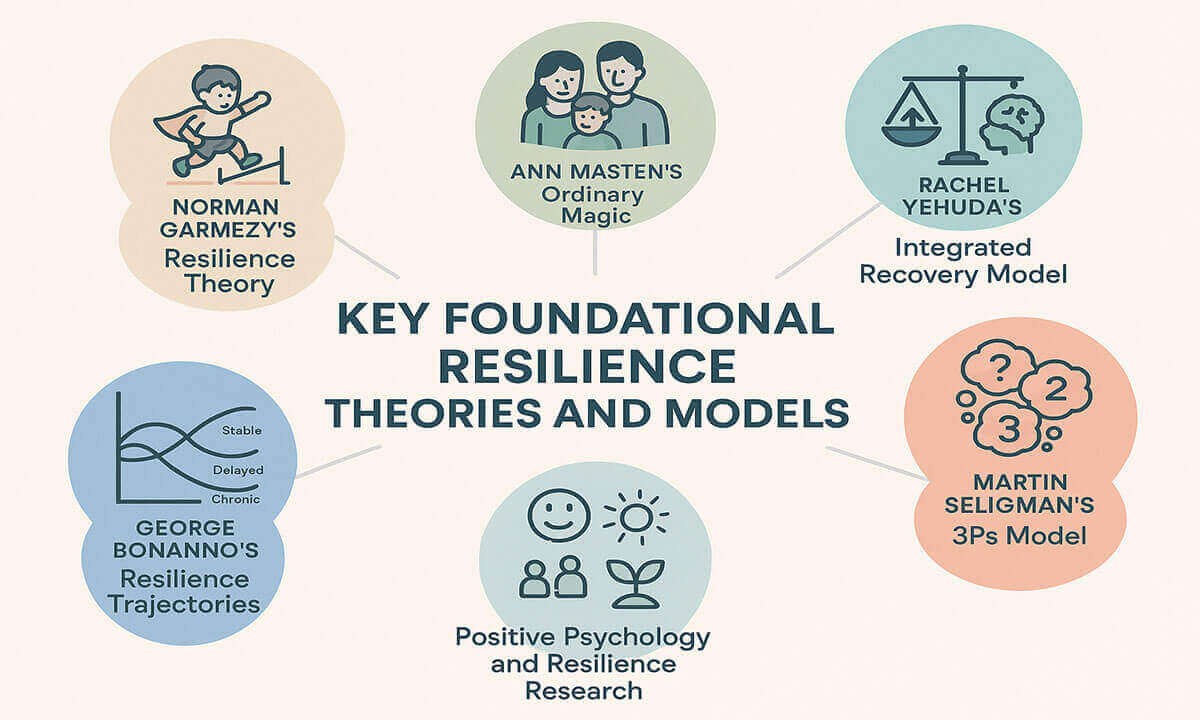

Key Foundational Resilience Theories and Models:

Why do some individuals thrive despite adversity while others struggle to cope? This question has been central to psychology, trauma studies, and therapeutic practices for decades. Therapists and researchers have gone further to ask what life experiences, environments, or personality traits predispose people to adapt successfully while others develop stress disorders. Foundational resilience theories and models offer a framework for understanding these differences. They show us that resilience is not just about innate toughness but rather a process that unfolds across time, relationships, and systems of support (Southwick et al., 2014). Over the years, pioneers like Norman Garmezy, Ann Masten, George Bonanno, Rachel Yehuda, and Martin Seligman have provided essential models that shape how resilience is understood and applied in practice. From shifting the field’s focus away from pathology toward protective factors, to highlighting resilience as ordinary rather than extraordinary, these theories have significantly influenced both clinical practice and broader social perspectives. This article will explore the key foundational resilience theories and models, their applications, their integration into therapeutic settings, the role of positive psychology in resilience research, and some criticisms of resilience theory.

Norman Garmezy’s Resilience Theory:

Norman Garmezy is widely regarded as the father of modern resilience research because he was among the earliest psychologists to systematically study how some children managed to succeed in life despite being born into high-risk environments. These environments often included conditions such as parental mental illness, substance abuse, poverty, and unstable family systems. Instead of focusing only on the damaging effects of these risk factors, Garmezy shifted attention toward identifying the protective mechanisms that allowed some children not just to survive but to thrive (Masten & Cicchetti, 2012).

His groundbreaking studies in the 1970s and 1980s represented a major paradigm shift in developmental psychology. Until then, psychology was primarily concerned with pathology, disease, and dysfunction. Researchers and clinicians often asked, “What is wrong with this child?” or “What deficits explain their problems?” Garmezy’s work broke this mold. He began asking questions that centered on strengths and adaptability: “What helps this child cope? What resources, relationships, or personal traits are sustaining them?” This shift from a deficit-based model to a strength-based perspective laid the foundation for resilience research as a legitimate scientific field.

One of Garmezy’s most influential contributions was the Project Competence Studies, a long-term research initiative that tracked children across different life stages. Through this work, he discovered that resilience was not a rare or extraordinary quality. Instead, it was a set of adaptive processes supported by both internal traits and external factors. Internally, children who exhibited problem-solving abilities, optimism, and emotional regulation were more likely to withstand adversity. Externally, strong attachments to supportive caregivers, positive peer relationships, and stable community resources acted as protective buffers against chronic stress (Masten & Cicchetti, 2012).

Garmezy’s research also revealed that resilience is dynamic rather than static. It is not something that a child either possesses or lacks, but rather a process that develops through interaction between individual characteristics and environmental influences. For instance, a child living in poverty might face multiple stressors but could still thrive academically and emotionally if they had access to a nurturing teacher, a supportive peer group, or extended family members who provided stability. This highlighted the fact that resilience must always be understood within the broader ecological context in which a person lives.

Another important aspect of Garmezy’s work was his role in transforming psychology’s orientation from pathology to prevention. By showing that children in high-risk environments were capable of positive adaptation, he laid the groundwork for interventions aimed at strengthening protective factors. His research inspired future generations of psychologists to design programs that emphasized skill-building, mentorship, and community engagement rather than simply treating symptoms of stress or trauma after the fact.

Perhaps what makes Garmezy’s contribution especially powerful is the spirit behind his inquiry. He reframed the narrative around children facing adversity. Instead of labeling them as “broken” or “damaged,” his perspective honored their strengths and capacities. In doing so, he also opened the possibility of building a science of human strength within adversity, one that could be studied empirically and applied in clinical and educational contexts.

In many ways, Garmezy’s theory marked the birth of resilience psychology as a distinct field. His ideas continue to influence current research and therapeutic practices, especially in how clinicians conceptualize the role of protective factors in helping individuals endure and adapt to challenges. As Masten and Cicchetti (2012) emphasize, his work was instrumental in redirecting developmental psychology toward the study of competence, adaptation, and growth, which remain central themes in resilience research today.

Ann Masten’s “Ordinary Magic”:

Ann Masten’s contributions to resilience theory represent one of the most influential developments following Norman Garmezy’s pioneering work. Building on his emphasis on protective factors, Masten introduced the idea that resilience is not rare or extraordinary but rather something grounded in ordinary processes of human development. She famously referred to resilience as “ordinary magic”, a phrase that captures the notion that resilience arises from common, everyday systems of support such as caregiving, attachment, problem-solving, and community stability (Masten, 2014).

What made Masten’s perspective groundbreaking was her rejection of the idea that resilience is a superhuman trait. Earlier perspectives sometimes unintentionally portrayed resilient individuals as exceptional, almost heroic figures who managed to overcome adversity through sheer willpower or unusual talent. Masten’s research demonstrated that resilience is not reserved for the extraordinary but is accessible to all individuals through the everyday functioning of protective systems. According to her, the true magic of resilience lies not in rarity but in its ordinariness—it emerges from the natural interaction between human beings and their environments.

Her research has consistently shown that resilience is rooted in basic adaptive systems. These include secure attachment relationships with parents or caregivers, effective emotional and behavioral regulation, cognitive competence, problem-solving abilities, and the availability of supportive social networks. In fact, her findings indicated that when these ordinary systems are intact and nurtured, children and adults are far more likely to adapt positively even when faced with chronic stress or traumatic experiences (Masten, 2014).

A critical implication of Masten’s work is that resilience can be nurtured and strengthened. Since it is not an innate superpower but a set of processes tied to human development, it can be supported through intentional interventions. For example, ensuring stable caregiving, promoting positive educational environments, and fostering community connections are all ways to strengthen resilience in children and adults. This has been particularly important for therapists, educators, and policymakers, as it provides practical strategies for building resilience at both individual and societal levels.

Masten’s idea of “ordinary magic” also expands the meaning of resilience beyond mere survival. Resilience, in her framework, is about thriving in the face of adversity, not just enduring it. This view acknowledges that resilience involves growth, adaptation, and meaning-making rather than simply bouncing back to a pre-crisis state. Such an understanding aligns closely with strengths-based approaches in therapy and coaching, where the emphasis is on helping individuals and families build on what is already working in their lives rather than focusing solely on deficits.

Another important contribution of Masten’s theory is her focus on resilience as a systemic and relational process. She argued that resilience does not reside within an individual alone but is shaped by broader social and ecological contexts. Families, schools, neighborhoods, and communities all play a role in fostering or undermining resilience. This ecological perspective highlights that resilience cannot be fully understood or supported without considering the multiple systems in which a person is embedded.

For therapists and coaches, Masten’s work provides a hopeful and empowering message. It reassures both practitioners and clients that resilience is not something mystical or unattainable. Instead, it can be cultivated through ordinary processes of care, connection, and support. Her research encourages practitioners to focus on strengthening these everyday systems rather than searching for rare qualities in individuals.

In brief, Ann Masten’s concept of “ordinary magic” redefined resilience as a normal part of human development, shaped by basic adaptive systems that can be strengthened and nurtured across the lifespan. By removing the mystique around resilience and situating it within ordinary processes, she helped shift resilience theory into a more practical and inclusive framework. As a result, resilience is no longer seen as an exceptional gift but as a universal capacity for adaptation that emerges when individuals are embedded in supportive environments and relationships.

George Bonanno’s Resilience Trajectories:

George Bonanno has been one of the most influential contemporary researchers in the field of resilience, particularly through his work on mapping how individuals adapt to highly adverse life events over time. His contributions stand out because they are grounded in large-scale longitudinal studies that track people before, during, and after trauma or loss. Unlike earlier models that viewed resilience as either present or absent, Bonanno demonstrated that resilience can take multiple trajectories depending on the individual, the type of adversity, and the surrounding context (Bonanno & Burton, 2013).

One of the central insights from Bonanno’s work is the concept of resilience as a trajectory rather than a single outcome. He defines resilience as a stable pattern of healthy functioning following adversity, but emphasizes that not everyone follows the same path. His research identified several distinct adaptation patterns:

- Minimal-impact resilience – Many individuals experience an adverse event but continue functioning with little or no significant disruption. Their emotional and behavioral functioning remains relatively stable, showing that resilience can often be the most common response to trauma.

- Delayed recovery – Some individuals initially struggle after adversity, showing signs of distress or dysfunction, but eventually regain stability over time. This pattern suggests that resilience does not always appear immediately but can unfold gradually as coping strategies and support systems take effect.

- Chronic dysfunction – A smaller group of individuals continues to struggle significantly and persistently after trauma. This pattern highlights that not everyone is resilient in the same way, and some require longer-term therapeutic or systemic interventions to recover.

These trajectories reveal that resilience is not a rare quality but a common human response that can vary in timing and intensity depending on individual and contextual factors (Bonanno & Burton, 2013).

Another major contribution of Bonanno’s theory is his emphasis on regulatory flexibility. Unlike earlier resilience theories that focused heavily on traits or stable characteristics, Bonanno argued that resilience is shaped by a person’s ability to flexibly adapt their coping strategies to meet the demands of the situation. For example, the same coping mechanism that works in one context may be ineffective in another. A person may need to express emotions openly in one situation but regulate or suppress them in another to maintain stability. This flexibility in self-regulation, rather than rigid adherence to one strategy, is a critical determinant of resilience (Bonanno & Burton, 2013).

Bonanno’s research also challenged the assumption that resilience is rare. Through his studies on bereavement, trauma, and loss, he consistently found that the majority of people show resilient responses after major life events. For instance, his work on individuals who lost loved ones revealed that most participants did not develop chronic grief or trauma symptoms but instead displayed stable psychological functioning over time. This finding runs counter to the traditional view that adversity inevitably leads to long-term psychological harm.

From a therapeutic perspective, Bonanno’s model carries important implications. First, it normalizes resilience as a typical outcome rather than an exception, which can be empowering for clients who fear that their struggles are signs of weakness. Second, his emphasis on regulatory flexibility provides a practical focus for therapy. Clinicians can help clients identify when a particular coping strategy is serving them well and when it might be hindering their recovery. By enhancing clients’ adaptive flexibility, therapists can support them in navigating diverse challenges more effectively.

Bonanno’s trajectory model also broadens the scope of resilience research by showing that it is measurable and observable over time. This has helped move resilience theory into a more scientific domain, where outcomes can be studied with empirical precision. Longitudinal data allow researchers to distinguish between temporary distress and long-term dysfunction, painting a more nuanced picture of how humans recover from adversity.

In exact, George Bonanno’s resilience trajectories framework provides a powerful and evidence-based understanding of how people adapt to trauma and loss. By recognizing multiple patterns of adaptation, emphasizing regulatory flexibility, and demonstrating that resilience is common, his work reshapes how psychologists, therapists, and the general public view human responses to adversity. It shifts the narrative from seeing resilience as exceptional to recognizing it as a normal and diverse process, deeply influenced by how individuals regulate themselves and adapt across time.

Rachel Yehuda’s Integrated Recovery Model:

Rachel Yehuda’s work on resilience represents a critical shift in the way psychologists understand adaptation after trauma. Unlike earlier models that tended to divide individuals into two categories—resilient or symptomatic—Yehuda and her colleagues challenged this dichotomy. Through extensive research on trauma survivors, particularly those with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Yehuda argued that resilience and ongoing symptoms can coexist. Her integrated recovery model emphasizes that resilience is not the absence of suffering but the ability to move forward while still carrying aspects of trauma (Yehuda et al., 2013).

One of the most important insights of Yehuda’s model is that resilience is not a fixed state that people either possess or lack. Instead, it is a dynamic process of reintegration. Survivors of trauma may continue to experience flashbacks, nightmares, or anxiety, yet still demonstrate resilience by actively engaging in life, pursuing meaning, and adapting in ways that allow them to grow. This approach recognizes that trauma leaves lasting marks, but those marks do not prevent individuals from leading purposeful and fulfilling lives.

Yehuda describes this process as a reconstruction of the self. Trauma often shatters one’s sense of identity, safety, and continuity. The integrated recovery model highlights how survivors rebuild their identities by weaving trauma into their life narrative in a way that acknowledges both pain and strength. This does not mean denying or erasing suffering, but rather integrating it into a broader story of survival, learning, and growth. In this sense, resilience is about transformation, where individuals develop new capacities, perspectives, and insights because of their experiences rather than in spite of them.

A distinctive feature of Yehuda’s framework is its acknowledgment of post-traumatic growth. Many survivors report not only recovering from trauma but also experiencing profound personal development. They may discover deeper empathy, stronger relationships, a clearer sense of purpose, or a renewed appreciation for life. The integrated recovery model provides space for these experiences, framing resilience as a journey that honors both ongoing struggles and newfound strengths.

Yehuda’s work has significant implications for clinical practice. Traditional approaches often aimed to eliminate all symptoms of trauma as the definition of successful treatment. However, Yehuda encourages therapists to view healing in broader terms. A client may still experience intrusive memories or hypervigilance but could simultaneously demonstrate resilience through their ability to sustain relationships, maintain work, or engage in meaningful pursuits. Therapists guided by this model focus less on eradicating symptoms and more on supporting the client’s ongoing adaptation and ability to find meaning despite those symptoms.

Her research also sheds light on the biological and neurobiological underpinnings of resilience. Yehuda has extensively studied the neuroendocrine system, stress hormones, and genetic factors in trauma survivors, demonstrating that biological changes accompany psychological adaptation. This integration of biological and psychological perspectives adds depth to the model and underscores resilience as a multi-layered process that involves mind, body, and environment.

Furthermore, Yehuda’s approach is deeply validating for survivors. Many trauma survivors feel pressured to “get over it” or “bounce back,” which can create shame when symptoms persist. By reframing resilience as compatible with ongoing symptoms, Yehuda’s model reduces stigma and honors the lived reality of trauma survivors. It acknowledges that healing does not always mean the absence of pain, but rather the courage to continue moving forward with insight, intention, and adaptability.

In clear-cut, Rachel Yehuda’s integrated recovery model offers a compassionate and realistic understanding of resilience. It shifts the focus from a binary view of either brokenness or strength to a nuanced perspective that embraces both suffering and growth. By seeing resilience as a dynamic process of reintegration, this model provides a framework that is both clinically practical and deeply humane. It teaches us that resilience is not about erasing the scars of trauma but about carrying them in ways that allow individuals to live fully, purposefully, and authentically.

Martin Seligman’s 3Ps Model of Resilience:

Martin Seligman, a pioneer in positive psychology, made an important contribution to resilience theory with his 3Ps model, which explores how trauma survivors interpret and explain their experiences. His framework identifies three common cognitive distortions that often intensify suffering after adversity: personalization, pervasiveness, and permanence (Seligman, 2006). These beliefs are widespread among trauma survivors, yet they are also malleable. By challenging and reframing them, individuals can foster resilience, restore hope, and begin to rebuild their lives.

- Personalization refers to the belief that one is entirely to blame for what happened. Trauma survivors often internalize guilt and self-blame, seeing themselves as the sole cause of events beyond their control. For example, a survivor of abuse might wrongly believe that they invited or deserved the harm. Seligman’s framework emphasizes that helping clients disentangle responsibility is essential. In therapy, this may involve exploring the broader context, clarifying where accountability truly lies, and introducing practices of self-compassion. By reframing self-blame, survivors can replace destructive narratives with healthier, more accurate perspectives that promote healing (Copley, 2023).

- Pervasiveness is the belief that trauma has contaminated every aspect of life. Survivors who hold this view often feel that their suffering defines them completely, making it difficult to see areas of strength, connection, or joy. For instance, a person who has experienced a devastating loss may struggle to find meaning or pleasure in any domain of life, perceiving the trauma as all-encompassing. Therapists applying Seligman’s model work to help clients reclaim areas of competence, identity, and relationships that remain untouched or that can be rebuilt. This process restores balance and perspective, showing survivors that while trauma is profound, it does not dictate every dimension of their existence.

- Permanence is the belief that the pain will never end, that the trauma has created a permanent state of despair or dysfunction. Survivors may feel stuck in their suffering, unable to envision a future in which healing is possible. Seligman emphasizes that this belief can be particularly damaging because it strips away hope, a key ingredient in resilience. Therapeutic work in this area often involves presenting evidence of change, both from clinical experience and the client’s own history. By highlighting how emotions, memories, and symptoms evolve over time, therapists can help clients recognize that trauma does not have to define their entire future. With care, intention, and support, healing remains possible.

The strength of Seligman’s 3Ps model lies in its practical application within trauma-informed therapy. It gives therapists a structured way to address the distorted cognitive patterns that prolong suffering. Instead of merely asking, “What’s wrong with me?” clients are invited to consider new questions: “What happened to me? How am I interpreting it? And how might I experience it differently?” This shift moves the therapeutic conversation away from pathology and toward possibility, aligning with broader resilience frameworks that emphasize strength and growth.

Another important aspect of Seligman’s work is its connection to positive psychology. By focusing on how people explain and reframe their experiences, his model aligns with the idea that resilience is nurtured by cultivating optimism, meaning-making, and self-trust. Survivors who learn to challenge the three Ps are not only less likely to remain stuck in trauma but are also more likely to engage in growth-oriented behaviors, such as rebuilding relationships, setting new goals, and embracing life with a renewed sense of agency.

For clinicians, Seligman’s model provides a powerful reminder that resilience is not simply about enduring adversity but also about transforming how it is understood. By targeting personalization, pervasiveness, and permanence, therapists can help clients rewrite their narratives in ways that foster healing, empowerment, and hope.

In thoroughgoing, Martin Seligman’s 3Ps model of resilience highlights the profound role of interpretation in shaping recovery from trauma. Personalization, pervasiveness, and permanence may distort how survivors see themselves and their futures, but with therapeutic intervention, these beliefs can be challenged and reframed. By shifting the narrative from self-blame and hopelessness to self-compassion and growth, Seligman’s framework empowers individuals to move forward with resilience. It underscores that resilience is not only about surviving adversity but also about reshaping meaning, restoring trust, and envisioning a future beyond suffering.

Positive Psychology and Resilience Research:

Positive psychology has become a central force in deepening our understanding of resilience, particularly in recent years. Where earlier approaches often emphasized pathology, dysfunction, or the elimination of symptoms, positive psychology has shifted attention toward strengths, growth, and wellbeing. In this framework, resilience is not defined merely as “bouncing back” from adversity but as cultivating the inner and outer resources that allow people to thrive despite challenges (Kalisch et al., 2021).

One of the key contributions of positive psychology is its focus on the role of positive emotions in building resilience. Research has demonstrated that emotions such as joy, gratitude, and hope do not simply provide temporary relief during hardship; they expand an individual’s capacity to think clearly, solve problems, and form supportive relationships. For example, Holmedal Byrne and Gustafsson (2024) found that positive emotions lay the foundation for long-term wellbeing by creating psychological flexibility and promoting adaptive coping. This suggests that cultivating positive affect is not about ignoring suffering but about creating mental and emotional space for constructive responses to adversity.

Another important insight from this body of research is the connection between meaning-making and time perspective. Resilient individuals often hold a strong sense of purpose and maintain a future-oriented mindset. Even during periods of suffering, they are able to frame their experiences within a larger life narrative that emphasizes growth, learning, or service to others. Molina-García et al. (2021) showed that individuals who possess a clear sense of meaning and a hopeful perspective on the future tend to report higher levels of resilience and greater life satisfaction. This underscores the fact that resilience is not just about enduring difficulty but also about how people interpret adversity and integrate it into their identities.

Positive psychology has also provided valuable insights into interventions that actively increase resilience. Studies have shown that practices such as self-compassion, gratitude exercises, and relational repair can significantly improve resilience, even in individuals experiencing severe psychological distress. For instance, interventions focused on cultivating self-compassion help clients replace self-blame with kindness and acceptance, which reduces emotional pain while increasing psychological strength (Holmedal Byrne & Gustafsson, 2024). Similarly, relational repair—restoring trust and connection in interpersonal relationships—has been shown to foster resilience by rebuilding social support networks that act as buffers against stress.

An especially significant finding in this area is that resilient individuals tend to prioritize resourcefulness over toughness. Bonanno and Westphal (2024) noted that resilient people do not simply push through hardships with grit or stoicism. Instead, they display adaptability by knowing when to seek help, when to rely on others, and when to change course. This challenges the traditional stereotype of resilience as mental toughness alone and reframes it as a flexible, relational process. It also validates the idea that asking for support is not a weakness but an essential aspect of resilience.

From a clinical perspective, positive psychology encourages therapists to move beyond a symptom-reduction model and instead focus on cultivating clients’ existing strengths. This involves helping clients recognize the qualities, skills, and relationships that have already sustained them, while also guiding them in developing new practices that nurture wellbeing. In trauma therapy, for example, this might include building routines that emphasize meaning-making, fostering emotional regulation, and intentionally cultivating positive emotions to counterbalance distress.

The integration of positive psychology into resilience research also offers a broader, more hopeful outlook for both individuals and communities. It shows that resilience is not just about minimizing damage but about expanding potential. Even in the aftermath of profound adversity, individuals can develop new perspectives, form deeper connections, and discover renewed purpose. This understanding aligns resilience more closely with concepts like post-traumatic growth and human flourishing.

In precise, positive psychology and resilience research together highlight that resilience is not simply the absence of dysfunction but the presence of adaptive capacities. Positive emotions enhance problem-solving and social connection, meaning-making provides direction and purpose, and interventions like self-compassion and relational repair actively strengthen resilience. By emphasizing resourcefulness and support-seeking, this field reframes resilience as a deeply human process rooted in relationships, perspective, and growth. Ultimately, positive psychology teaches us that resilience is not just about surviving adversity but about using it as a foundation for greater wellbeing, purpose, and connection.

Applying Resilience Theory in Practice:

Resilience theory has moved beyond being a purely academic concept and has become a valuable framework for practical applications in education, healthcare, workplaces, therapy, and community development. Applying resilience theory in practice involves translating its core principles, such as adaptability, emotional regulation, meaning-making, and supportive relationships, into strategies that help individuals and communities thrive despite adversity.

In education, resilience theory is particularly influential as teachers and administrators aim to support students not only academically but also emotionally and socially. Resilience-informed approaches focus on fostering protective factors such as problem-solving skills, self-efficacy, and positive peer relationships. For example, programs that teach growth mindset, encourage mentorship, and promote social-emotional learning help students develop coping strategies when facing academic stress, family challenges, or social pressures. Schools that integrate mindfulness, goal-setting, and collaborative learning create environments where setbacks are seen as opportunities for growth rather than signs of failure. Research indicates that resilience-based education improves academic outcomes while also enhancing long-term wellbeing and adaptability.

In healthcare and mental health settings, resilience theory is applied to improve patient outcomes and support those experiencing chronic illness, trauma, or psychological distress. Interventions often focus on strengthening psychological resources rather than simply reducing symptoms. Trauma-informed therapy, for instance, emphasizes clients’ strengths, helping them rebuild a sense of control and find meaning after distressing experiences. Healthcare providers themselves benefit from resilience-informed practices, including mindfulness, reflective journaling, and peer support groups, which reduce burnout and maintain emotional balance. Integrating resilience into healthcare encourages both recovery and personal growth, allowing patients and providers to navigate challenges more effectively.

In workplaces, resilience theory informs employee wellbeing initiatives and organizational culture. Resilience-focused programs teach adaptive coping strategies, promote effective communication, and foster supportive leadership. Employees are guided to manage stress, collaborate effectively, and maintain work-life balance. Leaders who prioritize flexibility, transparency, and empathy create environments where employees feel supported during times of change or high demand. In high-stress industries such as healthcare, emergency services, and finance, resilience-based strategies reduce burnout, improve job satisfaction, and strengthen team cohesion, while empowering individuals to adapt to evolving challenges.

Therapists and counselors use resilience theory to help clients recognize that their struggles do not define them and can become sources of growth and learning. Resilience-based therapy emphasizes clients’ existing resources, such as social support, personal strengths, and past successes. Techniques such as narrative therapy help clients reframe their life stories, highlighting survival, adaptation, and personal growth. Cognitive-behavioral strategies support the development of resilient thought patterns. This approach validates vulnerability while fostering active coping and personal agency, guiding clients to see themselves as active participants in their recovery.

Communities also benefit from resilience theory through programs designed to prepare for and recover from collective challenges such as natural disasters, economic crises, or social inequities. Community resilience initiatives focus on building social networks, fostering shared identity, and ensuring access to resources. In disaster recovery, for example, programs often create support centers and long-term recovery planning that integrates emotional, social, and material needs. Such approaches recognize that resilience is not only an individual capacity but a collective process that emerges through cooperation, shared meaning, and mutual support.

Policy and governance applications of resilience theory involve preparing societies to respond to uncertainty and adversity. Public health initiatives, economic safety nets, and disaster preparedness programs incorporate resilience principles to support populations effectively. Policies informed by resilience prioritize prevention, adaptability, and access to resources. Educational policies may include funding for school counseling services, while urban planning may focus on creating environments that can withstand natural disasters while promoting social cohesion.

Individuals can also apply resilience theory in their daily lives. Practices such as mindfulness, cultivating supportive relationships, setting realistic goals, and prioritizing self-care enhance personal resilience. Reframing challenges as opportunities for learning and growth strengthens emotional regulation and problem-solving capacity. Resilience in personal development emphasizes balancing acceptance of difficulty with proactive steps toward wellbeing, ensuring that vulnerability is acknowledged while adaptability and growth are cultivated.

In essence, applying resilience theory in practice demonstrates that resilience is not an abstract concept but a practical framework for strengthening individuals, organizations, and communities. Through strategies that emphasize adaptability, relational support, and meaning-making, resilience allows people and societies to navigate adversity while fostering growth, transformation, and collective strength.

Criticisms of Psychological Resilience Theories:

While resilience has become one of the most studied topics in psychology and wellbeing research, its theoretical frameworks are not without criticism. Scholars have pointed out several conceptual, methodological, and ethical concerns that highlight the need for a more nuanced understanding of resilience. These criticisms are important because they prevent the concept from being oversimplified or misused, ensuring that resilience research and interventions remain meaningful, culturally sensitive, and supportive rather than burdensome.

- Conceptual Ambiguity: One of the main criticisms of resilience theories is that the concept itself is often too broad or vague. Different researchers and clinicians define resilience in different ways: some see it as a personality trait, others as a process, and still others as an outcome (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013). This lack of clarity makes it difficult to measure resilience consistently or to compare findings across studies. For example, a person may be considered “resilient” in one study because they recovered quickly from stress, while another study may define resilience as long-term thriving after adversity. Without a universally agreed-upon definition, the risk is that resilience becomes a “catch-all” term that loses its precision.

- Overemphasis on the Individual: Another concern is that many resilience theories focus heavily on individual traits or coping strategies, sometimes neglecting the social, cultural, and structural factors that shape people’s ability to withstand adversity. Critics argue that by centering resilience within the individual, there is a danger of overlooking systemic issues such as poverty, discrimination, violence, or lack of access to healthcare. In this sense, resilience discourse can unintentionally shift responsibility away from governments, institutions, or communities, and place the burden of survival solely on the individual (Joseph, 2013). For instance, telling marginalized groups to simply “be more resilient” risks minimizing the structural inequalities they face.

- Pathologizing Normal Responses: Some researchers caution that resilience theories may inadvertently pathologize those who struggle after trauma. By framing resilience as the “ideal” response, people who experience ongoing distress might feel stigmatized or believe they are somehow failing. This concern is particularly relevant in trauma contexts, where recovery is often non-linear and deeply personal. Bonanno (2004) has argued that resilience should be seen as one of many valid pathways after adversity, not as a standard against which all survivors are measured. Otherwise, the concept risks creating unrealistic expectations for survivors and adding guilt or shame to their suffering.

- Cultural Limitations: Many resilience theories were originally developed within Western contexts, which can limit their relevance when applied across diverse cultures. For example, Western theories often emphasize autonomy, individual achievement, or self-efficacy, while other cultures may place greater importance on community, spirituality, or collective identity as sources of resilience (Ungar, 2012). Applying a one-size-fits-all model risks overlooking these differences and imposing culturally biased frameworks. Critics emphasize the need for more culturally grounded definitions of resilience that recognize how meaning, values, and coping strategies vary across societies.

- Measurement Challenges: Measuring resilience remains a methodological challenge. Many resilience scales rely on self-reports, which are subject to biases such as social desirability or memory distortions. Additionally, resilience is often dynamic and context-dependent—it may change over time, across different life domains, or in response to specific challenges. Yet most measurement tools treat it as a static trait. This raises questions about whether resilience can be accurately captured by standardized surveys or whether more flexible, context-sensitive approaches are needed (Windle, 2011).

- The “Resilience Fetish”: Some scholars have criticized what they call the “resilience fetish” in psychology and policy discourse. This refers to the widespread tendency to glorify resilience as a universal solution to adversity, often without sufficient attention to prevention or systemic change. For example, in workplaces, employees are often encouraged to undergo resilience training to cope with stress, while little is done to address the underlying causes of burnout, such as excessive workloads or toxic organizational cultures. Critics argue that this overemphasis on resilience can depoliticize suffering by suggesting that individuals should adapt to unjust conditions rather than demand structural improvements (Neocleous, 2013).

- Neglect of Vulnerability and Rest: Finally, resilience theories have been critiqued for not paying enough attention to the role of vulnerability, rest, and recovery. The constant emphasis on “bouncing back” or “thriving” may create pressure to always perform strength and adaptability, leaving little room for acknowledging exhaustion, grief, or the need for retreat. Some contemporary scholars propose that resilience should not always mean pushing through but sometimes allowing space for vulnerability, acceptance, and healing (Luthar et al., 2015).

In specific, while resilience remains a valuable and widely applied concept, it is not free from limitations. The major criticisms revolve around conceptual vagueness, overemphasis on individual responsibility, cultural biases, measurement difficulties, and the risk of placing undue pressure on people to appear endlessly strong. These critiques highlight the importance of viewing resilience as contextual, relational, and dynamic, rather than as a static trait or universal prescription. By integrating these critiques, future resilience theories and practices can become more inclusive, compassionate, and effective.

In conclusion, foundational resilience theories have profoundly shaped how we understand human adaptation to adversity. From Garmezy’s focus on protective factors, to Masten’s “ordinary magic,” to Bonanno’s trajectories of resilience, Yehuda’s integrated recovery model, and Seligman’s 3Ps framework, these theories provide rich perspectives on how individuals cope with challenges.

Positive psychology has expanded this field, showing that resilience is nurtured through emotions, meaning, and community. At the same time, critical voices remind us to avoid oversimplification and to account for cultural and systemic contexts.

Ultimately, resilience is not about denying suffering or glorifying survival but about recognizing the human capacity to adapt, grow, and find meaning even in the face of hardship. By integrating these theories into practice, therapists, coaches, and educators can help individuals move from pathology to possibility, honoring both the pain and the strength that shape the human experience.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is resilience?

Resilience is the ability to adapt, recover, and grow in response to adversity, stress, or trauma. It involves psychological, emotional, and social resources that allow individuals and communities to maintain or regain functioning after challenging experiences. Resilience is not a fixed trait but a dynamic process that can be nurtured and strengthened over time.

Can resilience be developed or is it innate?

Resilience can be cultivated. While some individuals may naturally possess certain traits that support coping, research shows that resilience is largely shaped by life experiences, relationships, and access to supportive systems. Practices such as mindfulness, self-compassion, emotional regulation, and building strong social connections can enhance resilience at any stage of life.

What are some key theories of resilience?

Several foundational frameworks help explain resilience. Norman Garmezy focused on protective factors in children growing up in high-risk environments. Ann Masten emphasized that resilience is “ordinary magic,” built from everyday supportive systems. George Bonanno highlighted resilience trajectories, showing it as a stable pattern of healthy functioning over time. Rachel Yehuda introduced the integrated recovery model, emphasizing that resilience and symptoms can coexist. Martin Seligman’s 3Ps model explains how interpretations of trauma affect recovery. Positive psychology research adds insights about the role of emotions, meaning, and resourcefulness in resilience.

How can resilience theory be applied in practice?

Resilience theory can guide interventions in education, healthcare, therapy, workplaces, and communities. In schools, it supports social-emotional learning and problem-solving skills. In healthcare, it strengthens patients’ psychological resources and reduces provider burnout. In therapy, it emphasizes client strengths and adaptive coping. In workplaces, it informs leadership and employee wellbeing programs. Communities and policymakers use resilience frameworks to prepare for and recover from collective challenges, ensuring social, emotional, and material support.

What are common challenges or criticisms of resilience theory?

Critics point out that resilience theory can be too broadly defined and may overemphasize individual responsibility while neglecting systemic and social factors. Cultural biases, measurement difficulties, and the risk of pathologizing normal distress are also concerns. Additionally, resilience should not be romanticized, as enduring adversity does not always equate to healthy adaptation. Recognizing these limitations helps ensure that resilience interventions are inclusive, compassionate, and effective.

What role does positive psychology play in resilience?

Positive psychology emphasizes cultivating strengths, meaning, and wellbeing alongside coping skills. Positive emotions, purpose, future-oriented thinking, self-compassion, and relational repair all contribute to resilience. Research shows that resilient individuals prioritize resourcefulness and social support over mere mental toughness, using these strategies to thrive despite challenges.

Is resilience the same as post-traumatic growth?

While resilience and post-traumatic growth are related, they are not identical. Resilience refers to maintaining or regaining functioning after adversity, whereas post-traumatic growth involves experiencing positive psychological changes, such as greater appreciation of life, stronger relationships, or new personal insights, as a result of struggling with adversity. Resilience can set the foundation for post-traumatic growth, but not all resilient individuals experience growth beyond recovery.

How can individuals strengthen their resilience?

Individuals can build resilience by cultivating emotional regulation, fostering supportive relationships, engaging in meaningful activities, developing problem-solving skills, practicing self-compassion, and maintaining a positive outlook. Recognizing past coping successes, seeking help when needed, and framing challenges as opportunities for growth are also key strategies. Resilience is a lifelong practice that can be reinforced through reflection, intentional action, and connection with others.

References:

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, Trauma, and Human Resilience: Have We Underestimated the Human Capacity to Thrive After Extremely Aversive Events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

- Bonanno, G. A., & Burton, C. L. (2013). Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613504116

- Bonanno, G. A., & Westphal, M. (2024). The three axioms of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 37(5), 717–723. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.23071

- Copley, L. A. (2023). Loving you is hurting me: A new approach to healing trauma bonds and creating authentic connection. Hachette/Balance.

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological Resilience: A Review and Critique of Definitions, Concepts and Theory. European Psychologist, 18, 12-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

- Holmedal Byrne, K., & Gustafsson, B. M. (2024). Implementation study of “Building Resilience,” including positive psychology interventions and positive emotion regulation training in patients with severe mental illness in an adult outpatient psychiatric mental health setting: An exploratory clinical trial. Behavior Modification, 48(5–6), 537–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/01454455241269842

- Joseph, C. (2013). Advanced Credit Risk Analysis and Management. Croydon: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118604878

- Kalisch, R., Köber, G., Binder, H., Ahrens, K. F., Basten, U., Chmitorz, A., Choi, K. W., Fiebach, C. J., Goldbach, N., Neumann, R. J., Kampa, M., Kollmann, B, Lieb, K., Plichta, M. M., Reif, A., Schick, A., Sebastian, A., Walter, H., Wessa, M., … & Engen, H. (2021). The frequent stressor and mental health monitoring-paradigm: A proposal for the operationalization and measurement of resilience and the identification of resilience processes in longitudinal observational studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 710493. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.710493

- Luthar, S. S., Grossman, E. J., & Small, P. J. (2015). Resilience and adversity. In M. E. Lamb & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Socioemotional processes (7th ed., pp. 247–286). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy307

- Masten, A. S. (2014). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. Guilford Press.

- Masten, A. S., & Cicchetti, D. (Eds.). (2012). Risk and resilience in development and psychopathology: The legacy of Norman Garmezy. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 333–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000016

- Molina-García, L., Castillo, I., & Queralt, A. (2021). Cross-sectional study of resilience, positivity and coping strategies as predictors of engagement-burnout in undergraduate students: Implications for prevention and treatment in mental well-being. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, Article 596453. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.596453

- Neocleous, M. (2013). Resisting Resilience. Radical Philosophy, 178. Retrieved From https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/commentary/resisting-resilience

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. Vintage Books.

- Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), Article 25338. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338

- Ungar, M. (2012). Social ecologies and their contribution to resilience. In M. Ungar (Ed.), The social ecology of resilience (pp. 13–32). Springer.

- Windle, G. (2011) What Is Resilience? A Review and Concept Analysis. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 21, 152-169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0959259810000420

- Yehuda, R., Daskalakis, N. P., Desarnaud, F., Makotkine, I., Lehrner, A. L., & Koch, E. (2013). Epigenetic biomarkers as predictors and correlates of symptom improvement following psychotherapy in combat veterans with PTSD. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4, Article 118. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00118

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College