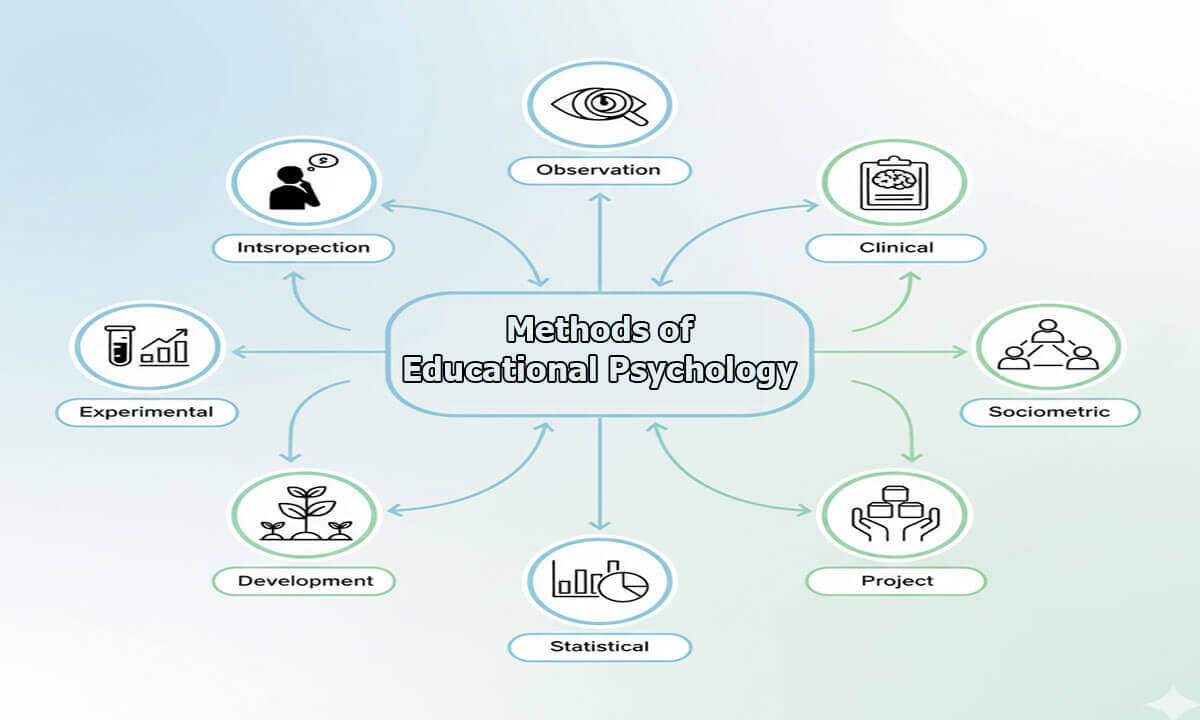

Methods of Educational Psychology:

Educational psychology is the scientific study of learning processes, psychological aspects of teaching, and the social contexts of education (Woolfolk, 2017). To understand how students think, feel, and behave in educational settings, researchers in this field rely on multiple research methods. Each method offers different windows into cognition, motivation, emotion, and behaviour; each also has trade-offs in validity, reliability, generalizability, and ethics. In practice, researchers often combine methods (a “mixed methods” approach) to triangulate findings and produce more robust conclusions (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). In the rest of this article, we will explore some of the essential methods of educational psychology: introspection, observation, experimental, case-study, developmental (genetic), clinical, sociometric, project, and statistical methods.

1. Introspection Method: The introspection method involves the subject carefully observing and reporting their own internal mental processes—thoughts, images, feelings, sensations—while or immediately after undertaking a task (e.g., solving a problem). The participant is both the observer and the observed (i.e. subject and instrument). This was one of the earliest methods in psychology (Wundt’s structuralism) and has often been used to probe conscious experience (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

Example: A student is assigned a memory task (e.g. recall a list of words) and then asked to write down what thoughts, strategies, or mental images came to mind during recall (for instance, “I grouped words into categories in my mind,” or “I tried to visualize each word”).

Strengths.

- It gives direct access to subjective experience—something no other method can provide fully.

- It is inexpensive and requires no complex instrumentation.

- For certain phenomena (e.g. feeling states, imagery), introspective reports may yield unique qualitative insights.

Limitations:

- Introspective reports are inherently subjective and not verifiable by independent observers; reliability and validity are limited (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

- It is difficult or impossible for many mental processes (especially unconscious ones) to become fully accessible to introspection.

- The act of introspecting may itself alter the mental process being observed (i.e. reactivity).

- It is poorly suited for children, animals, or persons with limited verbal or metacognitive capacity.

Because of these issues, introspection has largely been supplanted in modern psychology, though it still plays a role in phenomenological or qualitative traditions (Overgaard, 2010).

2. Observation Method: Observation involves systematically watching and recording behaviour as it occurs, either in natural settings (naturalistic observation) or in more controlled settings (structured observation). An observer may be visible (participant or non-participant) or hidden, and structured using checklists, rating scales, or coding schemes (Kozulin, 2003).

Example: A researcher sits in a classroom and records how often students raise their hands, engage in off‐task talk, or ask questions during a lesson. Alternatively, in a playground setting, an observer records instances of children initiating play, peer rejection, or conflict.

Strengths:

- Behaviour is recorded in context, making observations ecologically valid (i.e. real behaviour rather than hypothetical).

- It is less reliant on self-report and thus sidesteps introspection’s biases.

- It is particularly useful for children or nonverbal populations (who may not articulate their internal states).

- Good for generating hypotheses for further study.

Limitations:

- Observer bias: what the observer chooses to notice, record, or emphasize can distort findings.

- Reactivity or the “observer effect”: individuals may change behaviour when they know they are being watched (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

- Some behaviours or internal states (e.g. motivations, thinking) remain hidden and must be inferred.

- In natural settings, controlling extraneous variables is difficult, complicating causal inference.

- Coding and analysis may be laborious, and interrater reliability must be assured (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

3. Experimental Method: The experimental method seeks to establish cause–effect relationships by manipulating one or more independent variables (IVs) and observing the effect on a dependent variable (DV), while controlling extraneous variables. Pretest–posttest controls, random assignment, counterbalancing, and control groups are common features (Shadish et al., 2002).

Example: A researcher tests whether a “flipped classroom” instructional approach leads to better test performance compared to traditional lecture. Two comparable groups of students are randomly assigned; one group experiences the flipped format (IV), and both groups’ test scores (DV) are compared afterward.

Strengths:

- High internal validity: when well-done, experiments allow strong inference about causality (Shadish et al., 2002).

- The method is replicable, and control over extraneous variables reduces confounds.

- Quantitative data is amenable to rigorous statistical analysis.

Limitations:

- Artificiality: lab or tightly controlled classroom settings may not reflect real educational contexts (thus limiting external validity).

- Ethical constraints: not all manipulations are permissible (e.g. withholding beneficial instruction).

- Some educational phenomena are not easily manipulable (e.g. long‐term development, personality traits).

- Participants may not behave “naturally” under experimental conditions.

- The cost, time, and logistical demands can be high (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

4. Case Study Method: A case study is an intensive, in‐depth investigation of a single individual, group, institution, or phenomenon over time, using multiple sources of data (interviews, observation, documents, tests) (Yin, 2014). In educational psychology, case studies are especially useful for understanding special or atypical learners, complex interventions, or contextual phenomena.

Example: A school psychologist follows a student with dyslexia across a school year, collecting data from teacher interviews, standardized reading tests, classroom observation, family history, and writing samples, in order to understand the student’s difficulties and develop appropriate interventions.

Strengths:

- Provides a rich, nuanced, holistic understanding of a case in its real context.

- It is well-suited for exploring rare, complex, or contextual phenomena.

- It can generate hypotheses, guide theory refinement, or illustrate principles (Yin, 2014).

Limitations:

- Limited generalizability: one case may not represent the population.

- Vulnerable to researcher bias and interpretation errors.

- Resource-intensive: time, effort, and access are required.

- Ethical challenges: confidentiality, participant burden, and researcher influence must be carefully managed.

5. Developmental (Genetic) Method: The developmental (also called genetic) method studies how behaviour, cognition, emotion, and other psychological attributes change over time (Siegler, 2006). Common designs include:

- Longitudinal design (same participants measured repeatedly over time)

- Cross-sectional design (different cohorts of different ages tested at one point in time)

- Sequential design (combining cross-sectional and longitudinal)

- Microgenetic design (very frequent observations over a critical change period to capture process of change) (Siegler, 2006).

Example: A researcher measures children’s working memory capacity at age 5, 7, 9, and 11 (longitudinal). Or one tests cohorts of 5-, 7-, and 9-year-olds at the same time (cross-sectional). Or one uses a microgenetic method to observe how a child acquires a new strategy for mental arithmetic over many sessions in a short period.

Strengths:

- Captures developmental trends and trajectories (how change occurs).

- Helps distinguish age effects vs cohort effects (in sequential designs).

- Microgenetic designs can reveal mechanism and process of change, not just endpoints.

Limitations:

- Longitudinal studies face attrition (dropouts), time demands, and practice effects.

- Cross-sectional designs confound age with cohort (historical) differences.

- Microgenetic designs demand intense sampling and resources; generalizability is limited to moments of rapid change.

- It can be difficult to isolate causes (other variables may co‐vary with age).

6. Clinical Method: The clinical method is akin to a flexible, interview‐based, semi-structured case method, where the researcher probes a participant’s thoughts, feelings, reasoning, and background, adapting as new data emerges. It is used often in educational psychology and counseling to diagnose, intervene, and understand individual differences (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

Example: In a child guidance clinic, an educational psychologist meets with a student struggling in school, conducts interviews with the student, family, teacher; administers psychological assessments, observes in class; forms and tests hypotheses about cognitive, emotional, or motivational barriers; and uses that insight to tailor intervention.

Strengths:

- Flexible, responsive to emerging information.

- Good for in-depth understanding and tailoring intervention.

- Integrates qualitative and quantitative data.

Limitations:

- Lower generalizability.

- Risk of bias from the clinician’s theoretical orientation or subjective interpretation.

- Ethical and confidentiality concerns are more acute.

- Requires high skill and time investment.

7. Sociometric Method: The sociometric method, developed by Jacob L. Moreno, assesses the social relationships within a group (e.g. friendships, peer acceptance, rejection) by peer nominations, ratings, or sociograms, thereby mapping group structure, cliques, isolates, leaders, and social dynamics (Moreno, 1934).

Example: In a classroom of 30 students, the teacher asks each student to name three classmates they prefer to work with and three they least prefer. These nominations are coded to produce sociometric status (e.g. popular, rejected, neglected) and sociograms (graphical maps of social links).

Strengths:

- Provides concrete data on peer relationships and group structure.

- Useful for planning interventions (e.g. grouping strategies, reducing social isolation).

- Reflects social dimensions of classroom life often overlooked by traditional cognitive/achievement metrics.

Limitations:

- Risk of harm: some children may feel excluded or stigmatized if low status is revealed.

- Responses may be influenced by popularity, social desirability, or peer pressure.

- Sociometric status may change over time (temporal instability).

- Typically captures only one aspect (social preference) and not full personality or cognition.

8. Project Method: The project method is primarily an instructional strategy (originating in progressive education) in which students engage in purposeful, real-world inquiry or tasks (e.g. designing, investigating, producing). As a method in educational psychology, it can be used as an intervention under study: comparing learning, engagement, motivation, and outcomes under project-based instruction versus traditional instruction.

Example: In a science class, students are asked to design a small hydroponics system as a semester project, conducting background research, building prototypes, collecting data, reflecting, and presenting findings. A researcher then measures learning gains, student motivation, and group dynamics, comparing participants to a control class taught by lecture.

Strengths:

- Encourages active, student-directed learning and higher-order skills (planning, inquiry, reflection).

- More authentic and motivating; integrates multiple domains (cognitive, social, communication).

- Provides a rich context for studying how students learn, collaborate, self-manage, and reflect.

Limitations:

- Outcomes can be harder to assess fairly (variability in student initiative, group dynamics).

- Requires substantial design, scaffolding, resources, and teacher skill.

- May be less efficient or feasible in large classes or rigid curricula.

- Comparisons to traditional methods may be confounded by factors such as novelty, teacher enthusiasm, or student selection bias.

9. Statistical Method: The statistical method refers to the use of quantitative techniques to analyze data obtained via experiments, observations, surveys, or tests. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies), inferential tests (t-tests, ANOVAs, regressions, structural equation modeling), and more advanced psychometric models (e.g. item response theory) are included (Chen, Li, & Ying, 2021).

Example: After administering a motivation questionnaire and mathematics test, a researcher uses regression to predict test scores from motivational variables; uses factor analysis to identify underlying dimensions of motivation; or compares mean test gains between experimental and control groups. Also, in sociometric data, centrality measures and graph theory metrics may be applied.

Strengths:

- Enables summarization, generalization, and hypothesis testing across large samples.

- Can detect patterns, relationships, and effect sizes that might not emerge via qualitative inspection.

- Allows control for covariates and testing of mediation, moderation, or causal models.

- Advanced models (e.g. IRT) improve measurement precision and validity (Chen et al., 2021).

Limitations:

- The strength of inference depends on sample quality (size, representativeness, measurement validity).

- Statistical significance may not equate to educational/practical significance.

- Overreliance on statistical models can obscure contextual, individual, or qualitative nuance.

- Misuse or misinterpretation (e.g. p-hacking, ignoring assumptions) is a risk.

Integrative Use & Methodological Complementarity:

In practice, no single method meet requirements for every research question in educational psychology. Effective research often combines methods:

- An experiment might test whether a new instructional design improves outcomes; but concurrent observation can monitor how students behave (engagement, collaboration) under the new design.

- A case study or clinical investigation of a struggling student may reveal individual pathways, which can then guide the formulation of hypotheses and larger‐scale statistical studies.

- Developmental designs trace how learners change over time; statistical modeling helps quantify trajectories and identify predictors or moderators.

- Sociometric data can inform how peer relationships interact with academic motivation or performance.

Thus, method triangulation helps offset the weaknesses of any single approach and increases confidence in findings (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

In conclusion, the methods of educational psychology—introspection, observation, experimental, case study, developmental, clinical, sociometric, project, and statistical—offer diverse yet complementary approaches to understanding learning, development, motivation, and social dynamics in educational contexts. Introspection provides access to subjective experience (though with limitations); observation grounds us in overt behaviour; experiments allow causal inference (within constraints); case and clinical methods offer depth and individual nuance; developmental approaches chart change over time; sociometrics reveal social structure; project method bridges research and pedagogy; and statistical methods let us test, generalize, and model findings quantitatively.

No method is perfect: each has trade‐offs in validity, generalizability, resource demands, and ethical constraints. A well‐designed research program in educational psychology will judiciously select or combine methods appropriate to the research question, population, and context—and interpret results with awareness of each method’s boundaries.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What are the main methods used in educational psychology?

Educational psychology relies on several methods such as introspection, observation, experimental methods, case studies, developmental methods, clinical approaches, sociometric studies, project methods, and statistical techniques to understand learning, behavior, and teaching effectiveness.

Why is observation an important method in educational psychology?

Observation allows psychologists and educators to study behavior in natural classroom or social settings, providing authentic data about students’ interactions, learning habits, and challenges without interference.

How do experiments contribute to educational psychology research?

Experiments allow researchers to control variables and test cause-effect relationships, such as whether a new teaching method improves student performance compared to traditional methods.

What is the role of case studies in educational psychology?

Case studies provide detailed insights into individual learners or small groups, making them useful for understanding special needs, giftedness, or unique learning challenges.

How do developmental methods help in education?

Developmental methods study how learning and behavior change across different life stages, helping teachers adapt strategies to the age and developmental level of learners.

What is sociometry, and why is it used in classrooms?

Sociometry measures social relationships within a group, such as friendships or peer acceptance. It helps teachers understand group dynamics and address social isolation or bullying.

Why are statistical methods important in educational psychology?

Statistical methods are essential for analyzing test scores, surveys, and experiments. They help researchers draw valid conclusions and improve reliability and validity in findings.

Which method is most reliable in educational psychology?

No single method is universally reliable. The choice depends on research goals—experiments are strong for causality, observations for natural behavior, and case studies for depth. Often, a mixed-methods approach gives the best results.

How do these methods improve classroom teaching?

By applying findings from these methods, teachers can design more effective instruction, address student needs, and create supportive learning environments.

Are there ethical concerns in using these methods?

Yes, educational psychology research must protect student privacy, avoid harm, ensure informed consent, and maintain fairness when studying or testing learners.

References:

- Chen, Y., Li, X., & Ying, Z. (2021). Item response theory: A statistical framework for educational and psychological measurement. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2108.08604

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Eysenck, M.W., & Keane, M.T. (2015). Cognitive Psychology: A Student’s Handbook (7th ed.). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315778006

- Kozulin, A (2003). Psychological Tools and Mediated Learning. In A. Kozulin, B. Gindis, V. S. Ageyev and S. M. Miller (Eds.), Vygotsky’s educational theory in cultural context (pp. 15-38). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Moreno, J. L. (1934). Who Shall Survive? A New Approach to the Problem of Human Interrelations. Beacon House. Retrieved From https://reflexus.org/wp-content/uploads/whoshallsurvive.pdf

- Overgaard, M. (2010). How consciousness will change our view on neuroscience: Commentary on Lamme. Cognitive Neuroscience, 1(3), 224–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/17588928.2010.497585

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin.

- Siegler, R. S. (2006). Microgenetic Analyses of Learning. In D. Kuhn, R. S. Siegler, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Cognition, perception, and language (6th ed., pp. 464–510). John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

- Woolfolk, A. (2017). Educational psychology (13th ed.). Pearson.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.30.1.108

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College