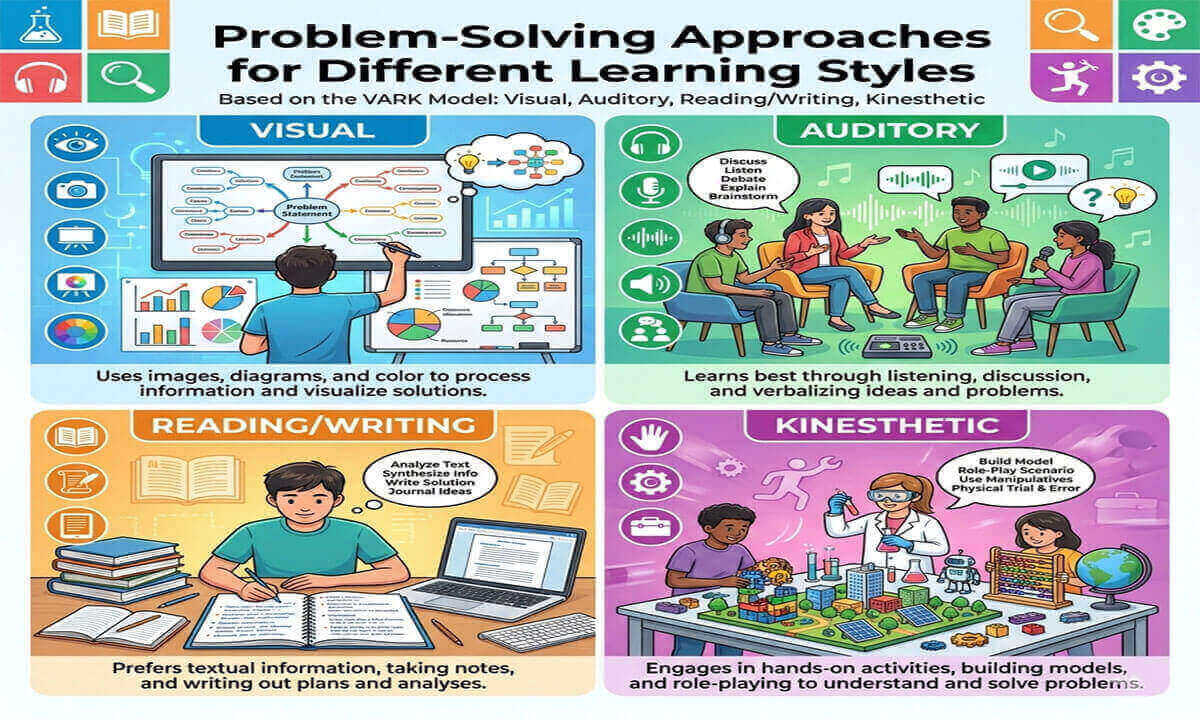

Problem-Solving Approaches for Different Learning Styles:

People do not learn in the same way. Some prefer visuals, others remember better by listening, writing, or physically engaging with information. These individual preferences are often referred to as learning styles, a concept widely discussed in educational psychology. One of the most recognized classifications is the VARK model, which divides learning preferences into four types: Visual, Auditory, Reading/Writing, and Kinesthetic (Fleming & Mills, 1992). Understanding these differences is essential because learning style influences how people approach challenges, process information, and solve problems. Problem-solving is not a one-method-fits-all process. When learners use approaches that fit their preferred learning style, they often think more clearly, retain information better, and solve problems more effectively (Liew et al., 2015). In the rest of this article, we will explore problem-solving approaches for different learning styles and how educators can adapt teaching to support diverse learners.

Understanding Learning Styles:

Learning styles refer to the preferred way individuals absorb, interpret, and retain information (Scott, 2010). The VARK model categorizes learners into:

- Visual Learners – Learn through images, charts, and spatial understanding.

- Auditory Learners – Learn best through listening and verbal discussion.

- Reading/Writing Learners – Prefer text-based input and output.

- Kinesthetic Learners – Understand through movement, hands-on activities, and physical experiences.

Although learners may show dominance in one category, most people benefit from a mixture of approaches (Fleming & Baume, 2006). Recognizing these styles helps individuals choose problem-solving strategies that align with how their brains process information.

Problem-Solving Approaches for Different Learning Styles:

1. Visual Learners (Seeing is Solving):

Visual learners are individuals who understand information best when it is presented in a visual format such as diagrams, charts, illustrations, flowcharts, and spatial layouts. They tend to think in pictures rather than words and often convert verbal information into mental imagery to make sense of it (Leite et al., 2010). When confronted with a new idea, they may pause to visualize it mentally before responding, which is why they often perform well when lessons include maps, graphic organizers, or symbol-based cues (Fleming & Mills, 1992). These learners usually appreciate neatly arranged content, highlighted notes, color separation, and visual order because it helps them process and store information more efficiently.

They also tend to have strong spatial awareness and may recall where information was located on a page rather than the exact wording itself. Visual learners often use drawing or doodling as a thinking tool, not out of distraction but as a way to mentally organize ideas. Studies show that presenting learning material visually enhances recall and comprehension for learners who naturally process information through sight (Leite et al., 2010). For them, understanding grows when they can literally see how one part of a problem connects to another.

Problem-Solving Approach: Visual learners solve problems most effectively when the issue is broken down visually. Instead of approaching a challenge through lengthy explanations or purely verbal reasoning, they need to externalize the problem in a visually arranged form. By turning unclear ideas into symbols, images, sketches, or stepwise diagrams, they are able to identify patterns, detect gaps, and plan solutions more clearly. Research suggests that visual representation of information supports deeper cognitive processing because it aids in organizing complex concepts in a structured manner (Fleming & Baume, 2006). In essence, visual learners do not just solve the problem—they picture it first.

Techniques that Support Problem-Solving for Visual Learners:

- Mind Maps: Mind maps convert a central issue into branches of related ideas. A learner can place the problem in the center and connect sub-points outward. This allows them to see how different elements link together rather than processing them in a linear way. This visual structure reduces cognitive overload and encourages creative exploration of solutions (Fleming & Baume, 2006).

- Flowcharts: A flowchart guides visual learners step-by-step from the problem to the outcome. Each box represents an action, decision, or pathway. Seeing the process laid out visually helps them break down a big challenge into manageable pieces. It becomes easier to identify where the problem lies and which step should come next.

- Color Coding: Using colors to classify details—such as red for challenges, green for solutions, and blue for resources—helps separate information into categories at a glance. Color-based organization improves memory recall for visually oriented students and enhances focus on priority areas (Leite et al., 2010).

Visual problem-solving can be compared to assembling a puzzle: once the pieces are spread out and visible, the picture begins to make sense. For a visual learner, clarity emerges not through discussion but through seeing structure, patterns, and connections.

2. Auditory Learners (Talk It Out):

Auditory learners make sense of information by hearing it. They understand concepts best when they are verbally explained, whether through discussions, lectures, podcasts, debates, or oral instructions. Rather than relying on visual representation or written notes, these learners internalize information by listening, speaking, and engaging in conversations (Gilakjani, 2012). They often remember tone, voice, and spoken examples more clearly than written text, and can recollect details from previous discussions even if they did not write anything down. Their learning process is rhythmic and sound-oriented, which is why many auditory learners enjoy reading aloud, repeating information verbally, or using mnemonic devices based on sound patterns.

This learning preference strongly influences how they approach problem-solving. When faced with a challenge, auditory learners often need to verbalize their thoughts to make sense of them. Speaking activates their reasoning process; hearing a concept explained aloud helps them identify errors, clarify missing information, and guide their thinking in a structured direction. Research indicates that auditory engagement—such as listening, discussing, or dialoguing—enhances comprehension for individuals who learn best through sound (Gilakjani, 2012). For them, silence can hinder thinking, while conversation stimulates it.

Problem-Solving Approach: Auditory learners solve problems most effectively through dialogue and discussion. They benefit from explaining the issue aloud to themselves or others, as speaking helps them process ideas that might remain unclear when confined to internal thought. They often ask questions, seek verbal feedback, and use conversation as a tool to break down complex elements. Hearing different viewpoints strengthens understanding, making collaborative brainstorming particularly useful. Instead of mapping information visually, these learners “untangle” problems through words and sound.

Strategies for Problem-Solving:

- Group Discussions and Brainstorming: Collaborative problem-solving works well because auditory learners can listen to multiple perspectives and refine their ideas through real-time feedback. Conversation provides them with sound-based cues, new viewpoints, and verbal reasoning pathways that lead toward solutions (Gilakjani, 2012).

- Self-Recording and Playback: When working individually, auditory learners can record themselves explaining the problem or brainstorming solutions. Listening to the playback helps them analyze their reasoning, catch gaps in logic, or discover new insights that were not obvious during the initial thought process. Hearing their own voice reinforces memory and enhances clarity.

- Verbal Repetition and Oral Summaries: Repeating instructions, summarizing key points aloud, or teaching someone else the concept improves retention. This technique strengthens memory pathways by converting information into sound—a form that aligns naturally with auditory processing.

For an auditory learner, solving a problem feels much like having a conversation with the challenge itself. They understand by hearing and think more effectively when ideas are spoken, questioned, discussed, and echoed back. Where visual learners see solutions, auditory learners hear them.

3. Reading/Writing Learners (Pen and Paper Power):

Reading/Writing learners are those who absorb information most effectively when it is presented in text form. They enjoy reading books, articles, instructions, and written explanations, and they prefer expressing themselves through writing. Their notebooks are often filled with organized notes, summaries, bullet points, or rewritten content because writing is not just a record—it is part of their thinking process. According to Fleming & Baume (2006), this learning group prefers tasks that involve reading, note-taking, and composition since written material offers structure, clarity, and personal control over information. They may also excel at vocabulary-based learning, academic writing, or tasks that require detailed documentation.

These learners approach problem-solving through logical language-based methods. They need to read about the issue to understand it and write about it to solve it. When faced with a challenge, they often start by gathering information through written resources, then translate those ideas into their own words. Writing enables them to organize thoughts step-by-step, which helps break down complex problems into manageable components. Research suggests that rewriting and summarizing content strengthens understanding and improves long-term retention for this type of learner (Fleming & Baume, 2006). For them, clarity emerges through text, not imagery or dialogue.

Problem-Solving Approach: The most effective path for reading/writing learners is to convert the problem into written form. They might write out the question, list possible causes, describe each step, or draft a paragraph explaining the issue. Seeing their thoughts in writing allows them to examine logic carefully, identify missing pieces, and refine their reasoning. Instructions, manuals, research articles, and written examples are valuable tools because text gives them time to analyze and reflect deeply before concluding.

Strategies for Problem-Solving:

- List-Making and Outlining: Writing lists of problem components, potential solutions, pros and cons, or sequential steps helps these learners structure the issue clearly. Lists transform confusion into order, making the solution more obvious through organization.

- Research and Reading Resources: Reading case studies, previous examples, or written explanations equips them with knowledge and patterns they can apply. Written information offers depth, context, and evidence—key elements for problem-based reasoning (Fleming & Baume, 2006).

- Note-Taking and Summarization: Rewriting problem details in their own words improves understanding because the act of writing reinforces ideas neurologically. Summaries act as personal clarifications, turning raw information into meaningful insight. Writing drafts or journaling through a problem can reveal answers during the process itself.

For reading/writing learners, solving a problem is like crafting an essay: they collect information, organize it, write through their reasoning, revise their ideas, and gradually uncover solutions. Text is both their tool and their pathway to clarity.

4. Kinesthetic Learners (Hands-On Problem Solvers):

Kinesthetic learners process information best through movement, touch, and real-world experiences. Instead of learning by watching or listening alone, they understand concepts when they physically interact with materials or engage in active experimentation. They may frequently move, fidget, tap feet, or prefer standing over sitting because bodily engagement stimulates their thinking. Research shows that kinesthetic learners thrive when they can manipulate objects, practice skills, or participate in activities that require physical involvement rather than passive observation (Romanelli et al., 2009). These learners often excel in environments where learning is connected to action—such as labs, workshops, role-play, sports, or hands-on demonstrations.

This learning style deeply affects how they approach problem-solving. Kinesthetic learners make sense of challenges by doing something with them. They might test different solutions physically, simulate the situation, or try several trial-and-error attempts to see what works. While visual learners draw and auditory learners speak, kinesthetic learners pick things up, move them around, build prototypes, or act out scenarios. Romanelli et al. (2009) highlight that bodily involvement enhances conceptual understanding because it allows learners to connect abstract knowledge with real experience. Simply put, action activates thought for these learners.

Problem-Solving Approach: Kinesthetic learners solve problems most effectively through physical engagement. They benefit from experimenting directly with materials, using manipulatives, or creating models to represent different elements of the problem. Instead of processing solutions mentally, they often need to test them in real time. Movement not only keeps them focused but also stimulates creative thinking. If stuck, a short walk or physical break can trigger new ideas—because motion fuels cognition.

Strategies for Problem-Solving:

- Physical Models and Manipulatives: Representing ideas with real objects—such as blocks for math, cards for planning steps, or physical layouts for design—helps kinesthetic learners visualize relationships by touching them. Manipulation makes abstract issues tangible and understandable (Romanelli et al., 2009).

- Role-Playing and Simulations: For conceptual or interpersonal problems, acting out scenarios enables learners to step inside the situation. Through simulation, they experiment with solutions, test reactions, and gain practical insights that reading or listening might not provide.

- Movement-Based Thinking Breaks: Kinesthetic learners often need to move to think clearly. Stretching, walking, or even reorganizing their workspace can improve focus. Physical activity boosts creativity and enables the brain to process information subconsciously during movement.

For kinesthetic learners, problem-solving is much like building or crafting: they must touch, test, move, and feel the components to truly understand them. Their solutions grow from action rather than theory alone, making learning an active exploration rather than a passive experience.

Blending Learning Styles (The Hybrid Advantage):

Most individuals are not purely one learning style. Using multiple techniques often strengthens problem-solving skills (Liew et al., 2015). A learner might:

- Draw a diagram (visual)

- Explain it aloud (auditory)

- Write down findings (reading/writing)

- Build a model (kinesthetic)

A blended approach encourages creativity and deep understanding by engaging multiple senses and cognitive pathways.

Adapting Problem-Solving for Education:

Recognizing that students possess different learning preferences is essential for effective teaching and problem-solving development. A one-size-fits-all instructional approach may leave some learners disengaged or struggling to understand content, whereas varied strategies create equitable learning opportunities for all. Research suggests that although learning style theories should not rigidly determine instruction, offering diverse modes of engagement significantly enhances comprehension and motivation (Liew et al., 2015). When educators intentionally incorporate visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic elements into lessons, students are more likely to connect with the material and develop strong problem-solving skills.

The classroom becomes more inclusive when students are given multiple pathways to explore ideas. For example, a math concept can be introduced through diagrams and charts (visual), explained aloud through discussion (auditory), followed with written practice exercises (reading/writing), and reinforced through manipulative tools or real-life applications (kinesthetic). Fleming and Baume (2006) emphasize that learning preferences function best when viewed as flexible tools rather than rigid labels. This means teachers do not need to teach four separate lessons but can blend strategies creatively within a single learning experience.

Another key aspect is helping students recognize their own strengths. Encouraging learners to reflect on which methods help them understand ideas faster allows them to develop metacognitive awareness—knowing how they learn, not just what they learn. When students understand their learning tendencies, they can independently select problem-solving strategies suited to the task at hand. This promotes autonomy, confidence, and self-regulated learning, which are vital skills for academic success and lifelong adaptability (Pashler et al., 2009).

Practical Ways Educators Can Adapt Problem-Solving Instruction:

- Offer Variety in Learning Activities: Rotate between visuals, discussions, reading materials, and hands-on tasks so that each lesson appeals to multiple learning processes. For example, begin with a visual demonstration, follow with class dialogue, assign a written reflection, and then conduct an experiment or project. Variety keeps students engaged and supports deeper learning.

- Encourage Student Choice: Provide options for how students can approach tasks or present solutions. Some may choose to design a flowchart, others to write an essay, record a voice explanation, or build a model. Allowing choice validates diverse strengths and encourages learners to explore new strategies (Bull & Keengwe, 2019).

- Create a Flexible and Supportive Classroom Environment: A rigid structure may limit students’ problem-solving potential. Instead, encourage movement breaks, collaborative tasks, visual workspaces, reading corners, and hands-on stations. Flexibility supports kinesthetic learners (Romanelli et al., 2009) while still benefiting others who use blended methods.

- Model Hybrid Problem-Solving: Teachers can demonstrate thinking processes aloud, sketch diagrams on the board, write out steps, or manipulate materials during explanations. Modeling integrated strategies helps students see that real-world problem-solving thrives on multiple approaches rather than a single method.

- Use Reflective Follow-Ups: After activities, ask students to reflect on which strategy helped them most and why. This builds awareness of personal learning habits, encourages experimentation, and strengthens cognitive flexibility—key qualities of effective problem solvers (Leite et al., 2010).

When educators embrace diversity in learning, students learn not only what to think but how to think. The classroom transforms into a space where exploring solutions becomes more meaningful, engaging, and accessible to all learners.

At the end of the day, we can say that problem-solving is a universal skill, but the path to finding a solution varies from person to person. Visual learners understand problems when they see them, auditory learners when they talk them out, reading/writing learners through text, and kinesthetic learners through action. Using problem-solving approaches that match learning styles not only increases engagement but also leads to more effective and lasting understanding. Whether you’re a student, teacher, or lifelong learner, knowing your learning preference is a powerful tool. Discovering how you learn means discovering how you solve—and that knowledge can transform challenges into opportunities.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Can a person belong to more than one learning style?

Yes, absolutely. Most people are blended learners who show strengths in more than one style. Someone may learn theory well through reading but need visual aids to fully grasp complex concepts, or they may understand instructions better when they hear them while taking notes. Learning preferences shift depending on the task, environment, and even mood. Recognizing multiple styles allows a learner to switch approaches, making problem-solving more flexible and effective.

Do learning styles affect how quickly we solve problems?

Learning styles don’t determine intelligence, but they do influence how we approach a challenge. When a task matches our preferred learning method—visual, auditory, reading/writing, or kinesthetic—we often process information faster and retain it better. Using the wrong approach doesn’t prevent learning, it just makes the process slower and sometimes frustrating. Matching learning strategies to personal style usually results in quicker understanding and higher confidence.

What if I don’t know my learning style yet?

If you’re unsure, observe what feels natural when learning something new. Do you draw diagrams? Prefer listening to explanations? Write notes automatically? Learn best by doing? Paying attention to these habits often reveals your dominant style. Another option is experimenting—try watching a video, reading text, discussing with a friend, or practicing hands-on. Whichever method leads to clarity and comfort is likely a strong part of your learning profile.

Can learning styles be developed over time?

Yes, learning styles are not fixed traits; they can grow and strengthen like skills. A visual learner can practice auditory strategies, a reading/writing learner can improve through hands-on projects, and so on. Developing multiple styles is valuable because real-life problem-solving isn’t always provided in your preferred format. Flexibility leads to resilience and better adaptability in academic, professional, and everyday situations.

How can teachers use learning styles to improve problem-solving skills in students?

Teachers can design lessons that include varied formats—diagrams, reading materials, discussions, and practical tasks—so all students find an entry point into understanding. Providing choice is powerful: allow students to write a summary, create a poster, present verbally, or build a model. When students are allowed to use their natural preferences, participation increases and problem-solving becomes more engaging and meaningful.

If I already solve problems well, do learning styles still matter?

Yes, because knowing how you think gives you control over the process. Even if you perform well, understanding your learning style helps you work smarter, not harder. You can choose techniques that reduce stress, improve recall, and speed up solutions. It also helps you assist others by recognizing that what works for you may not work for them.

What if a problem requires a learning style I’m not strong in?

This is where blending styles becomes an advantage. If one method feels difficult, switch to another approach. For example, if written instructions aren’t clear, convert them into diagrams or discuss them verbally. If theory seems abstract, try applying it physically. Using multiple styles acts like opening several doors to the same room—the solution becomes accessible through different paths.

References:

- Bull, P. H., & Keengwe, J. (Eds.). (2019). Handbook of research on innovative digital practices to engage learners. Information Science Reference/IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-9438-3

- Fleming, N.D. & Mills, C. (1992). Helping Students Understand How They Learn. The Teaching Professor, Vol. 7 No. 4, Magma Publications, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Fleming, N., & Baume, D. (2006). Learning Styles Again: VARKing up the Right Tree! Educational Developments, 7, 4-7.

- Gilakjani, A. P. (2012). Visual, auditory, kinesthetic learning styles and their impacts on English language teaching. Journal of Studies in Education, 2(1), 104–113. https://doi.org/10.5296/jse.v2i1.1007

- Leite, W. L., Svinicki, M., & Shi, Y. (2010). Attempted validation of the scores of the VARK: Learning styles inventory with multitrait–multimethod confirmatory factor analysis models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(2), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164409344507

- Liew, S. C., Sidhu, J., & Barua, A. (2015). The relationship between learning preferences (styles and approaches) and learning outcomes among pre-clinical undergraduate medical students. BMC Medical Education, 15, Article 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0327-0

- Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2009). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x

- Romanelli, F., Bird, E., & Ryan, M. (2009). Learning styles: A review of theory, application, and best practices. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 73(1), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj730109

- Scott, C. (2010). The enduring appeal of “learning styles”. Australian Journal of Education, 54(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494411005400102

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College