Protective Factors in Psychology:

Protective factors are crucial elements in the field of psychology that play a pivotal role in enhancing an individual’s resilience and reducing the likelihood of developing psychological disorders or experiencing adverse outcomes in the face of adversity or risk factors. These factors act as buffers, helping individuals cope with life’s challenges and promoting mental well-being. This article will delve into the concept of protective factors in psychology, discussing various types and examples.

Definition of Protective Factors:

Protective factors are characteristics, attributes, or circumstances that serve as buffers or shields against the development of mental health issues, psychological distress, or adverse outcomes, particularly in the presence of risk factors or challenging life circumstances (Masten, 2014). These factors act as positive influences that enhance an individual’s capacity to adapt, cope effectively, and maintain psychological well-being even when faced with adversity.

Importance of Protective Factors:

The importance of protective factors in psychology cannot be overstated, as they play a critical role in several key areas:

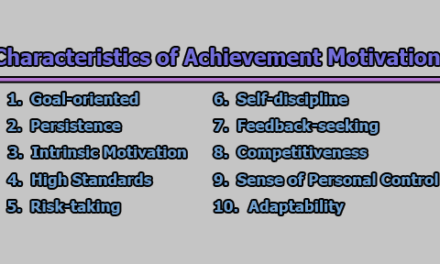

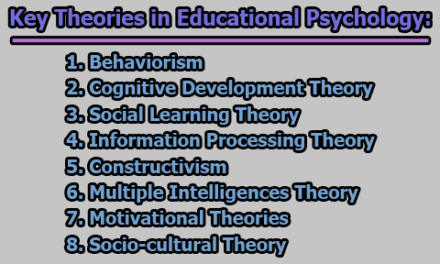

1. Resilience Promotion: Protective factors are fundamental to resilience, which is the ability to bounce back from adversity and grow stronger through challenging experiences (Rutter, 1987). By providing a cushion against the negative impacts of risk factors, protective factors enable individuals to endure hardship without succumbing to mental health problems.

2. Prevention and Intervention: Identifying and strengthening protective factors is crucial for designing effective preventive and intervention strategies. These strategies are essential for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers to reduce the likelihood of mental health issues and improve overall well-being (Masten & Motti-Stefanidi, 2020).

3. Holistic Well-being: Protective factors contribute to holistic well-being, encompassing not only the absence of mental illness but also the presence of positive psychological states. Factors like strong social support, self-efficacy, and optimism promote overall life satisfaction and fulfillment (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

4. Public Health: From a public health perspective, understanding and fostering protective factors can reduce the societal burden of mental health disorders. By addressing these factors, communities and policymakers can work towards healthier populations (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014).

5. Individual Empowerment: For individuals, recognizing and utilizing their own protective factors can empower them to take an active role in their mental health. This self-awareness can lead to more informed decisions and better strategies for dealing with life’s challenges.

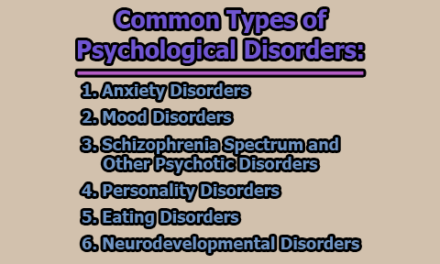

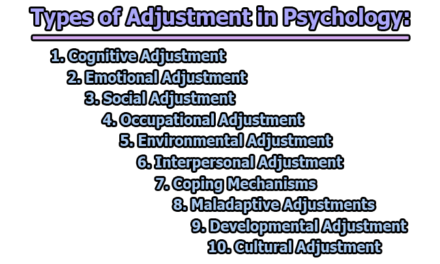

Types of Protective Factors in Psychology:

Protective factors in psychology can be categorized into various types, each contributing to an individual’s resilience and well-being. These protective factors serve as buffers against the development of mental health issues and other adverse outcomes. Here are some common types of protective factors:

1. Individual Protective Factors: Individual protective factors are inherent traits and personal characteristics that contribute to an individual’s resilience and well-being:

- Self-Efficacy: Self-efficacy, a concept developed by Bandura (1994), is the belief in one’s ability to successfully complete tasks and overcome challenges. Individuals with high self-efficacy tend to approach difficult situations with confidence and perseverance, making them more resilient in the face of adversity.

- Emotional Regulation: Emotional regulation involves the ability to recognize, manage, and cope with one’s own emotions effectively. People with strong emotional regulation skills can navigate stress and negative emotions more adaptively, reducing the risk of psychological distress (Gross, 2015).

- Optimism: Optimism, as discussed by Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000), refers to having a positive outlook on life and expecting favorable outcomes even in challenging circumstances. Optimistic individuals tend to cope better with stress and are less prone to depression.

- Coping Skills: Effective coping strategies, as described by Folkman and Lazarus (1988), involve problem-solving, seeking social support, and emotional regulation. Individuals who possess a repertoire of adaptive coping skills can better navigate stressors and setbacks.

- Adaptive Personality Traits: Certain personality traits contribute to resilience. For instance, adaptability, persistence, and a propensity for openness to new experiences, as highlighted in the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (Connor & Davidson, 2003), can facilitate one’s ability to bounce back from adversity.

2. Family Protective Factors: Family protective factors are elements within the family environment that enhance an individual’s resilience:

- Strong Social Support: Cohen and Wills (1985) emphasize that robust social support networks within families provide a safety net during difficult times. Supportive family relationships can mitigate the impact of stressors.

- Effective Communication: Walsh (2006) underscores the importance of open and effective communication within families. Healthy communication fosters understanding, emotional expression, and conflict resolution, contributing to family resilience.

- Stable Family Environment: A stable and nurturing family environment can promote emotional security and well-being. Stability and consistency in family life provide a foundation for resilience (Masten, 2014).

3. Community and Environmental Protective Factors: Factors in the broader community and environment also contribute to resilience:

- Access to Education: Quality educational opportunities empower individuals with knowledge and skills, enhancing their capacity to overcome challenges (Masten & Motti-Stefanidi, 2020).

- Safe Neighborhoods: Living in safe and supportive neighborhoods reduces exposure to violence and stress, promoting resilience (Sampson et al., 2002).

- Availability of Mental Health Services: Access to mental health care and support services is essential for individuals facing psychological challenges (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014).

- Positive Peer Relationships: Supportive and positive peer relationships can contribute to an individual’s sense of belonging and self-esteem (Brown, 1993). Such relationships provide social and emotional support.

4. Cultural and Ethnic Protective Factors: Cultural and ethnic factors that protect against adversity include:

- Cultural Resilience: Some cultural groups possess specific traditions, practices, and values that promote resilience (Ungar, 2008). These cultural assets can provide a source of strength during difficult times.

- Strong Cultural Identity: A strong connection to one’s cultural identity can offer a sense of belonging and purpose, bolstering one’s resilience (Sue & Sue, 2012).

5. Economic and Socioeconomic Factors: Economic and socioeconomic factors that can protect against adversity include:

- Financial Stability: Economic resources and financial stability can reduce stress related to financial hardship (Wadsworth, 2015). Financial security supports psychological well-being.

- Access to Healthcare: Adequate access to healthcare and health insurance can enhance both physical and mental well-being (Adler & Newman, 2002). Good health is a fundamental aspect of resilience.

6. School and Educational Factors: In the context of children and adolescents, school and educational factors can act as protective influences:

- Supportive Teachers and Mentors: Positive relationships with teachers and mentors at school can foster resilience and academic success (Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004).

- Engagement in Extracurricular Activities: Participation in extracurricular activities provides opportunities for skill development, social connection, and a sense of belonging (Mahoney et al., 2003).

Examples of Protective Factors:

Protective factors are crucial in promoting resilience and mental well-being by mitigating the impact of risk factors and adversity. Here are examples of protective factors:

- Regulatory Strengths:

- Endurance: Endurance is the ability to persist and maintain effort in the face of challenges and setbacks. It involves a high level of determination and tenacity, which allows individuals to continue working toward their goals even when obstacles arise. For example, a student who faces academic difficulties but continues to study diligently demonstrates endurance.

- Emotional Awareness: Emotional awareness refers to the capacity to recognize and understand one’s own emotions. It involves being in tune with one’s feelings, which can lead to better self-insight and the ability to identify sources of stress or emotional distress.

- Emotional Regulation: Emotional regulation encompasses a set of skills and strategies that enable individuals to manage their emotions effectively. This includes techniques such as deep breathing, mindfulness, and cognitive reframing. People who excel in emotional regulation can navigate emotionally charged situations with composure.

- Coping: Coping refers to the adaptive strategies individuals use to deal with stress and adversity. It can involve problem-focused coping (addressing the source of stress) or emotion-focused coping (managing the emotional response to stress). Effective coping strategies can help individuals maintain psychological well-being during challenging times.

- Honesty and Integrity: Honesty and integrity involve being truthful, trustworthy, and adhering to ethical principles. These qualities foster trust and positive relationships with others. Individuals who value honesty and integrity tend to have more stable and supportive social networks.

- Anger Management Skills: Anger management skills encompass the ability to recognize anger, express it in healthy ways, and prevent it from escalating into aggressive or harmful behavior. These skills include techniques like relaxation exercises, communication, and problem-solving to address the underlying causes of anger.

- Meaning-Making Strengths:

- Purpose: Purpose in life provides a sense of direction and motivation. It involves having meaningful goals and a clear sense of one’s values. People with a strong sense of purpose tend to persevere through challenges because they believe their efforts have significance.

- Optimism: Optimism is the expectation of positive outcomes even in the face of adversity. Optimistic individuals tend to view setbacks as temporary and specific, which helps them maintain resilience and hope during difficult times.

- Religious Meaning-Making: Religious meaning-making involves finding strength, guidance, and a sense of purpose through religious or spiritual beliefs and practices. Faith and spirituality can provide comfort and resilience during challenging life events.

- Interpersonal Strengths:

- Generativity: Generativity is the concern for future generations and a desire to contribute positively to the well-being of others. It often manifests as mentoring, teaching, or supporting younger individuals, which can create a sense of fulfillment and social connectedness.

- Compassion: Compassion involves recognizing and empathizing with the suffering of others. Compassionate individuals are more likely to offer emotional support and assistance to those in need, contributing to strong social bonds and support networks.

- Social Support: Social support refers to the emotional, informational, or instrumental assistance provided by one’s social network, including family, friends, and peers. Having a reliable support system can buffer the effects of stress and adversity.

- Community Support: Community support includes access to resources and services available within the community, such as support groups, counseling, or community organizations. These resources can provide essential assistance during challenging times.

- Forgiveness: Forgiveness is the act of letting go of resentment and negative emotions toward someone who has caused harm. Cultivating forgiveness can lead to improved interpersonal relationships and reduced emotional distress.

- Generative Roles:

- Maternal Attachment: Maternal attachment represents the strong emotional bond and attachment between a mother and her child. This secure attachment fosters emotional security and support, which are foundational for a child’s development.

- Paternal Attachment: Similar to maternal attachment, paternal attachment involves the emotional bond between a father and his child. A supportive and nurturing paternal figure can significantly contribute to a child’s well-being and resilience.

- Individual:

- Positive Physical Development: Positive physical development includes maintaining good physical health through regular exercise, proper nutrition, and healthy lifestyle choices. Physical health is interconnected with mental well-being and can provide energy and resilience.

- Academic Achievement: Academic achievement reflects success in education, which not only opens doors to future opportunities but also boosts self-esteem and confidence in one’s abilities.

- High Self-Esteem: High self-esteem is a positive self-image and belief in one’s self-worth. It contributes to resilience by fostering a strong sense of self-efficacy and the ability to face challenges with confidence.

- Emotional Self-Regulation: Emotional self-regulation involves managing one’s emotions effectively, which can reduce the impact of stressors on mental health. Techniques such as relaxation, mindfulness, and emotional expression contribute to emotional self-regulation.

- Coping and Problem-Solving Skills: Coping and problem-solving skills encompass a range of adaptive strategies for dealing with stress. Problem-focused coping involves addressing the root causes of stress, while emotion-focused coping focuses on managing emotional responses.

- Engagement and Connections in Multiple Contexts: Engaging in multiple social contexts, such as school, peer groups, sports, employment, religion, and cultural activities, provides diverse sources of support and a sense of belonging. This broad network can offer different forms of assistance during challenging times.

- Family:

- Provides Structure, Limits, Rules, and Predictability: A family that establishes clear boundaries, expectations, and routines provides a stable and predictable environment. This predictability can offer a sense of security and reduce anxiety.

- Supportive Relationships: Supportive relationships within the family, characterized by love, trust, and open communication, create a nurturing and emotionally secure environment.

- Clear Expectations for Behaviors and Values: Families that communicate and reinforce expectations for behavior and values help children develop a strong moral foundation and a clear sense of right and wrong.

- School/Community:

- Mentors and Support for Development: Mentors and supportive figures in schools and communities guide individuals in developing their skills, interests, and goals. These mentors offer valuable guidance and encouragement.

- Engagement in School and Community: Actively participating in school and community activities provides a sense of belonging, purpose, and connection with others who share similar interests and values.

- Positive Norms: Exposure to positive social norms and values that discourage risky behaviors and promote prosocial behavior helps individuals make healthier choices and resist negative influences.

- Clear Expectations for Behavior: Clearly defined expectations for appropriate behavior within schools and communities create a structured and safe environment where individuals understand the boundaries and consequences of their actions.

- Physical and Psychological Safety: A physically and psychologically safe environment within schools and communities protects individuals from harm and promotes a sense of security, which is essential for well-being.

In conclusion, protective factors are vital components in psychology that contribute to an individual’s resilience and mental well-being. They encompass individual, family, and environmental factors and play a crucial role in mitigating the effects of adversity and risk factors. Recognizing and cultivating these protective factors is instrumental in the development of effective intervention and prevention strategies in psychology.

References:

- Adler, N. E., & Newman, K. (2002). Socioeconomic disparities in health: Pathways and policies. Health Affairs, 21(2), 60-76.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71-81).

- Brown, B. B. (1993). Adolescents’ relationships with peers. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder Jr., & K. Lüscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 253-278). American Psychological Association.

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310-357.

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76-82.

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Manual for the Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1-26.

- Mahoney, J. L., Harris, A. L., & Eccles, J. S. (2003). Organized activity participation, positive youth development, and the over-scheduling hypothesis. Social Policy Report, 17(4), 3-32.

- Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(1), 6-20.

- Masten, A. S., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2020). Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: Reflections in the context of COVID-19. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1(2), 97-106.

- Pianta, R. C., & Stuhlman, M. W. (2004). Teacher-child relationships and children’s success in the first years of school. School Psychology Review, 33(3), 444-458.

- Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57(3), 316-331.

- Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (2002). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918-924.

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Behavioral health barometer: United States, 2014. HHS Publication No. SMA-15-4895.

- Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2012). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice (6th ed.). Wiley.

- Ungar, M. (2008). Resilience across cultures. The British Journal of Social Work, 38(2), 218-235.

- Walsh, F. (2006). Strengthening family resilience (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Wadsworth, M. E. (2015). Development of maladaptive coping: A functional adaptation to chronic, uncontrollable stress. Child Development Perspectives, 9(2), 96-100.

Former Student at Rajshahi University