The Big 3 Approaches to Qualitative Data Collection: Structured, Semi-Structured, and Unstructured Interviews

Qualitative research is an indispensable tool for gaining deep insights into human experiences, behaviors, and perceptions. Within this realm, interviews serve as one of the most effective methods for collecting nuanced data. However, the success of this method largely depends on selecting the appropriate interview approach. Broadly, there are three types of interviews: structured, semi-structured, and unstructured. Each approach comes with its unique strengths and weaknesses, making them suitable for different research contexts. In the rest of this article, we are going to explore the Big 3 Approaches to Qualitative Data Collection, shedding light on their applicability, challenges, and advantages.

1. Structured Interviews:

Structured interviews are a type of qualitative data collection method where the interviewer uses a pre-determined set of questions administered in a standardized order. This approach is often compared to a questionnaire delivered in a conversational style, ensuring consistency across all respondents (Bryman, 2021). The primary objective is to reduce variability and ensure that all participants have a uniform experience, making their responses directly comparable (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2018).

This method is particularly advantageous when the research goal involves collecting comparable data from a large sample size. For instance, structured interviews are widely used in social research, healthcare studies, and market analysis, where quantifiable data is required (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2015).

Key Characteristics:

- Pre-defined Questions: All questions are crafted beforehand and asked in the same sequence.

- Uniform Delivery: Interviewers are trained to deliver questions in a standardized manner, avoiding deviations or personal interpretations.

- Focused Responses: The scope of responses is often restricted, leading to answers that align closely with the research objectives.

Advantages:

- Consistency and Comparability: The standardized format ensures that all participants answer identical questions, making it easier to compare responses across a large sample (Bryman, 2021). This is particularly useful in cross-sectional studies where generalizable data is needed.

Example: A structured interview can be used to survey patients’ satisfaction with healthcare services, using uniform questions about wait times, staff behavior, and facility cleanliness.

- Time Efficiency: Structured interviews are quicker to conduct than semi-structured or unstructured interviews, as the pre-defined format minimizes digressions. Additionally, data analysis is streamlined due to the uniformity of responses (Cohen et al., 2018).

Example: In a study involving 1,000 participants, structured interviews can save time by avoiding prolonged open-ended discussions.

- Objectivity and Reliability: By adhering strictly to a script, interviewer bias is significantly reduced, ensuring that the data remains objective and reliable (King & Horrocks, 2010).

- Ease of Replication: Structured interviews are easy to replicate in different settings or with different populations, which is ideal for validation studies or large-scale surveys (Patton, 2015).

Disadvantages:

- Limited Depth: The rigid structure of the interview may prevent participants from elaborating on their responses, potentially overlooking important insights or nuances (Bryman, 2021).

Example: If a participant expresses dissatisfaction with a service but cannot elaborate due to the restrictive format, the data might fail to capture the underlying issue.

- Inflexibility: Structured interviews do not allow for deviations or follow-up questions, which can limit the interviewer’s ability to explore unexpected but relevant topics (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2015).

Example: A participant might mention an unforeseen factor affecting their experience, but the structured format does not permit further exploration.

- Potential for Monotony: The repetitive nature of structured interviews can feel monotonous for both the interviewer and the participant, potentially affecting the quality of responses.

Applications:

Structured interviews are most suitable for scenarios where standardized data collection is essential.

- Large-Scale Surveys: For example, national demographic studies often employ structured interviews to ensure consistency across thousands of participants.

- Policy Evaluation: Government agencies may use structured interviews to assess the impact of social programs.

- Market Research: Structured interviews are commonly used to gather consumer feedback on products or services.

Steps to Conduct Structured Interviews:

- Design the Interview Guide: Develop clear, concise, and relevant questions that align with the research objectives. Avoid leading or ambiguous questions to ensure unbiased responses.

- Pilot Testing: Conduct a pilot test to evaluate the clarity and effectiveness of the questions, making adjustments as needed (Cohen et al., 2018).

- Training Interviewers: Ensure that interviewers are trained to deliver the questions in a consistent manner and manage time effectively.

- Data Collection: Conduct the interviews, ensuring adherence to the script and maintaining neutrality.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the data using statistical or thematic methods, depending on the nature of the responses.

Example Scenario:

A healthcare organization wants to assess patient satisfaction across multiple facilities. Using structured interviews, researchers ask patients identical questions about appointment scheduling, wait times, and staff demeanor. The data collected allows the organization to identify patterns and implement targeted improvements.

2. Unstructured Interviews:

Unstructured interviews are the most flexible and conversational method of qualitative data collection. Unlike structured interviews, which rely on a pre-determined set of questions, unstructured interviews allow participants to guide the discussion. This method prioritizes open-ended, free-flowing conversations to explore participants’ perspectives in depth (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2015). The interviewer takes on a facilitator role, ensuring that participants feel comfortable sharing their experiences without rigid constraints.

This approach is particularly valuable for exploratory studies, where the primary goal is to uncover rich, context-specific insights rather than produce standardized data.

Key Characteristics:

- No Pre-defined Structure: While there may be a general theme or research objective, specific questions are not pre-determined.

- Participant-Led: The discussion is guided by participants’ responses, enabling the researcher to delve into areas of interest as they emerge.

- Emphasis on Depth: Focus is placed on understanding complex emotions, experiences, or phenomena in a natural context.

Advantages

- Rich, Contextual Data: Unstructured interviews are ideal for collecting detailed, nuanced insights. They enable researchers to understand participants’ unique perspectives in their own words (Bryman, 2021).

Example: A study exploring survivors’ experiences of trauma can use unstructured interviews to gather highly personal and emotional narratives.

- Flexibility: The lack of a rigid format allows interviewers to adapt questions and pursue emerging themes. This flexibility often leads to unexpected but valuable findings (Patton, 2015).

Example: During an interview with small business owners, a participant might mention unforeseen challenges such as navigating digital marketplaces, prompting further exploration.

- Natural Conversation Flow: Unstructured interviews mimic casual dialogue, which can make participants feel more at ease and encourage honest, open responses (King & Horrocks, 2010).

Disadvantages:

- Time-Intensive: Conducting unstructured interviews requires significant time. The conversations are often lengthy, and the resulting data can be vast and complex to analyze (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2018).

Example: A single unstructured interview might last several hours, with additional time needed for transcription and thematic analysis.

- Difficulty in Comparisons: Due to the variability in responses, comparing data across participants can be challenging. This limitation makes unstructured interviews less suitable for studies requiring standardized data (Bryman, 2021).

- Dependence on Interviewer Skill: Successful unstructured interviews rely heavily on the interviewer’s ability to build rapport, listen actively, and steer the conversation without imposing bias (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2015).

Example: An inexperienced interviewer might struggle to maintain focus or miss opportunities to probe deeper into significant topics.

- Potential for Irrelevant Data: Without a structured framework, participants may go off-topic, leading to data that is less relevant to the research objectives (Patton, 2015).

Applications:

Unstructured interviews are particularly useful for:

- Exploratory Research: Ideal for understanding new or poorly researched phenomena.

- Personal Narratives: Effective for capturing personal stories, emotions, and experiences,

- Sensitive Topics: Useful for discussing delicate subjects where participants need freedom to express themselves.

Steps to Conduct Unstructured Interviews:

- Define Broad Research Objectives: Clearly identify the overarching theme or purpose of the study while avoiding overly specific questions.

- Build Rapport: Create a comfortable and trusting environment to encourage open communication.

- Encourage Open-Ended Responses: Use prompts like “Can you tell me more about that?” or “How did that make you feel?” to explore participants’ perspectives.

- Document the Conversation: Record the interview (with consent) and take detailed notes to capture both verbal and non-verbal cues.

- Analyze Themes: Use qualitative analysis techniques, such as thematic analysis, to identify patterns and insights in the data.

Example Scenario:

A sociologist researching the cultural significance of rituals in indigenous communities might use unstructured interviews. By allowing participants to freely describe their traditions, beliefs, and practices, the researcher can gain a deeper understanding of their lived experiences without imposing a predefined framework.

3. Semi-Structured Interviews:

Semi-structured interviews represent a middle ground between structured and unstructured approaches. This method involves a pre-determined set of open-ended questions, allowing flexibility for the interviewer to explore additional themes or probe deeper into specific responses (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2015). Semi-structured interviews are highly valued in qualitative research because they balance the consistency of structured interviews with the depth of unstructured interviews, making them suitable for a wide range of studies.

Key Characteristics:

- Guided Flexibility: The interviewer uses a list of guiding questions but can deviate to explore relevant topics introduced by participants.

- Open-Ended Questions: Questions encourage participants to elaborate on their experiences, perspectives, and feelings.

- Moderate Comparability: While some level of standardization exists, the flexibility can introduce slight variations between interviews.

Advantages:

- Balance Between Depth and Consistency: Semi-structured interviews allow for detailed exploration while maintaining enough structure to ensure comparability across participants (Bryman, 2021).

Example: A study on employee satisfaction could include questions about work culture but also explore personal anecdotes about workplace challenges.

- Flexibility in Probing: Researchers can ask follow-up questions to clarify or delve deeper into unexpected insights, ensuring richer data collection (Patton, 2015).

Example: If a participant mentions an innovative work habit, the interviewer can explore its impact on productivity.

- Participant-Centered: By combining structure with openness, participants feel free to share their thoughts without being confined by rigid questioning (King & Horrocks, 2010).

- Efficient Data Collection: While more time-intensive than structured interviews, the pre-prepared questions streamline the interview process compared to unstructured interviews (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2018).

Disadvantages:

- Skill-Dependent Execution: Conducting a successful semi-structured interview requires a skilled interviewer capable of balancing structure with flexibility (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2015).

Example: An inexperienced interviewer may fail to maintain focus, leading to irrelevant data or missed opportunities for deeper inquiry.

- Potential for Variability: The flexibility can lead to inconsistencies in how questions are asked, making cross-participant comparisons more complex (Bryman, 2021).

- Analysis Challenges: The diversity of responses can make thematic analysis time-consuming and resource-intensive (Patton, 2015).

Applications:

Semi-structured interviews are versatile and can be used in a variety of research contexts, including:

- Exploratory Studies: For example, investigating the impact of social media on mental health among teenagers.

- Policy Evaluation: Assessing the implementation of government policies by combining standardized questions with participant-specific discussions.

- Mixed Methods Research: Complementing quantitative findings with qualitative insights to offer a well-rounded perspective.

Steps to Conduct Semi-Structured Interviews:

- Prepare an Interview Guide: Develop a list of open-ended questions aligned with the research objectives. Include prompts for possible follow-up questions.

- Build Rapport: Create a comfortable environment for participants to encourage openness and trust.

- Follow the Guide, But Stay Flexible: Use the prepared questions as a foundation while allowing the conversation to flow naturally.

- Take Notes and Record: With participants’ consent, record the session and take notes to capture both verbal and non-verbal cues.

- Analyze and Interpret: Use thematic analysis or other qualitative methods to identify patterns and insights across responses.

Example Scenario:

A researcher studying the effects of remote work might prepare semi-structured interview questions focusing on productivity and work-life balance. However, if participants highlight challenges such as isolation or technology issues, the researcher can probe deeper into those topics to gain richer insights.

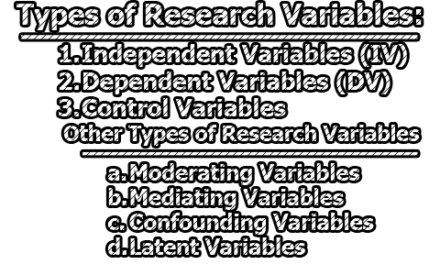

Choosing the Right Approach:

Selecting the appropriate interview approach depends on your research objectives and questions. Here are some considerations to guide your decision:

- Research Aims: If your goal is to validate a hypothesis or collect comparable data, structured interviews are ideal.

For exploratory research, where depth and unexpected insights are valued, unstructured interviews are preferable.

If you aim to strike a balance between depth and comparability, semi-structured interviews are the way to go.

- Sample Size: Structured interviews work well with large sample sizes due to their efficiency and consistency.

Unstructured and semi-structured interviews are better suited for smaller samples, where detailed insights are prioritized.

- Interviewer Expertise: Structured interviews require less skill, as they follow a script.

Unstructured and semi-structured interviews demand experienced interviewers who can navigate conversations and manage time effectively.

- Time and Resources: Structured interviews are quicker to conduct and analyze.

Unstructured interviews require significant time for both data collection and analysis.

Semi-structured interviews strike a middle ground in terms of time commitment.

It is apparent that in qualitative research, interviews are a powerful tool for uncovering deep insights. However, the choice between structured, semi-structured, and unstructured interviews can significantly impact the quality and relevance of the data collected. Structured interviews prioritize consistency and comparability, making them suitable for large-scale studies. Unstructured interviews offer unparalleled depth and flexibility, ideal for exploratory research. Meanwhile, semi-structured interviews provide a balanced approach, catering to studies requiring both depth and comparability.

Ultimately, the “right” approach depends on the unique needs of your research. By carefully considering your research aims, questions, and available resources, you can confidently select the most appropriate interview strategy. Armed with this understanding, you’ll be well-equipped to conduct meaningful interviews and generate valuable insights for your study.

References:

- Bryman, A., et al. (2021). Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780190853662. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/social-research-methods-9780190853662/

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research Methods in Education (8th ed.). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Research-Methods-in-Education/Cohen-Manion-Morrison/p/book/9781138209886/

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2015). InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- King, N., & Horrocks, C. (2010). Interviews in Qualitative Research. SAGE Publications.

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-research-evaluation-methods/book232962/

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College