The Neuroscience of Gratitude and Its Effects on the Brain:

Gratitude is more than just a polite response or a momentary feeling of thankfulness — it is a deeply transformative emotion that shapes how our minds and bodies function. Neuroscience has begun to uncover how practicing gratitude activates specific areas of the brain linked to reward, motivation, and emotional wellbeing, leading to long-lasting positive effects on mental health and resilience. From simple practices like keeping a gratitude journal to expressing appreciation toward others or the world around us, gratitude nurtures empathy, strengthens social bonds, and fosters a sense of fulfillment. Rooted in the Latin word gratia, meaning grace or thankfulness, gratitude has been recognized for centuries as a healing force, and modern science now confirms its profound impact on the brain and overall wellbeing. In the rest of this article, we will explore the neuroscience of gratitude and its effects on the brain.

What Is Gratitude? (A Neuroscientific Perspective):

In the field of positive psychology, gratitude is often described as the way we recognize and appreciate the good in our lives. It is more than a fleeting feeling of thankfulness — it is a positive emotional response that emerges when we acknowledge a benefit we have received or when we extend appreciation toward others (Emmons & McCullough, 2004). At its core, gratitude involves both cognitive recognition and emotional experience, reminding us of the connections we share with those who contribute to our wellbeing.

Yet gratitude extends beyond being just a pleasant emotion. It is a complex psychological phenomenon that requires us to recognize the role others play in enhancing our lives, thereby deepening our appreciation of positive outcomes and relationships. This makes gratitude a uniquely social emotion — one that not only enriches personal happiness but also strengthens bonds between individuals.

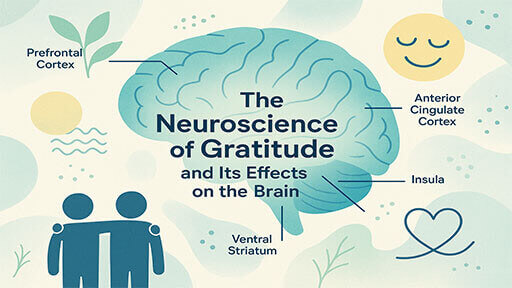

From a neuroscientific standpoint, researchers have identified that gratitude activates several important regions of the brain. These include the prefrontal cortex, responsible for higher-order thinking and decision-making; the anterior cingulate cortex, which helps regulate emotions; the ventral striatum, a central hub in the brain’s reward system; and the insula, which plays a key role in emotional awareness (Fox et al., 2015). Together, these areas form the foundation for how gratitude influences the way we process rewards, regulate emotions, and make decisions.

Understanding how these brain mechanisms work is still an ongoing area of study, but findings suggest that gratitude has far-reaching effects on our emotional resilience, social connections, and even physical health (Fox et al., 2015). When we engage in gratitude, it alters activity at the neurotransmitter level, creating physiological changes that give rise to feelings of happiness, satisfaction, and inner contentment (Fox et al., 2015).

Another fascinating aspect of gratitude is its association with moral cognition. Researchers hypothesize that when we feel grateful, our brains engage reward circuits that are not only linked to pleasure but also to social interactions and moral decision-making. This means gratitude helps us evaluate fairness, generosity, and reciprocity in our relationships. Neuroimaging studies show that these processes involve changes in the posteromedial cortex, insula, medial prefrontal cortex, and the nucleus accumbens, a region that lies at the heart of the brain’s reward system (Fox et al., 2015).

In short, gratitude is both a deeply emotional and neurologically grounded experience. It enhances our ability to connect with others, fosters resilience in the face of adversity, and nurtures overall mental and physical wellbeing — all while reshaping the very structure and function of the brain.

The Science of Gratitude (How It Changes the Brain):

Gratitude, while often thought of as a simple “thank you,” is far more complex than a social courtesy or a fleeting emotional state. Modern neuroscience demonstrates that gratitude activates multiple regions of the brain, influences neurotransmitter systems, and even reshapes brain structures over time. This growing body of evidence suggests that gratitude is not only good for our mood but also essential for resilience, wellbeing, and social connection.

Gratitude and Brain Activation: One of the most compelling findings in neuroscience is that gratitude engages regions of the brain involved in moral cognition, decision-making, and emotional processing. For example, research has shown that making moral decisions about gratitude activates the right anterior superior temporal cortex — an area associated with emotion, memory, autonomic functions, and reward-related processes (Zahn et al., 2008). This indicates that gratitude is not just about feeling good; it is a higher-order process that integrates social understanding, emotional regulation, and ethical reasoning.

Gratitude, the Nervous System, and Emotional States: At a neurobiological level, gratitude plays a role in calming the body’s stress responses. It helps regulate the sympathetic nervous system, which is typically responsible for “fight or flight” reactions and anxiety. On a psychological level, gratitude supports a mental shift away from negative rumination and toward more positive and constructive thought patterns (Wong et al., 2018). In other words, gratitude not only quiets the physiological stress response but also trains the mind to adopt a healthier, more optimistic outlook.

The role of the limbic system is also central in this process. The limbic system — which includes the thalamus, hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and cingulate gyrus — regulates much of our emotional life. Within this system, the hippocampus and amygdala are particularly responsive to gratitude. These structures govern memory formation, emotional learning, and bodily responses, and they become activated when we experience gratitude (Wong et al., 2018).

Importantly, the hypothalamus within this network has a direct link to the brain’s reward pathways. When stimulated through feelings of gratitude, it boosts the release of serotonin and activates the brainstem to produce dopamine, two key neurotransmitters associated with mood, pleasure, and motivation (Zahn et al., 2008). This explains why gratitude often leaves us with a lingering sense of warmth, calmness, and satisfaction.

Structural Changes in the Brain: Beyond temporary mood enhancement, gratitude has been linked to actual structural changes in the brain. Neuroimaging research has revealed that people who regularly practice gratitude exhibit increased gray matter volume in regions of the brain tied to cognitive functioning, learning, and decision-making (Zahn et al., 2014). Gray matter plays a critical role in processing complex tasks, sensory input, and voluntary movement, so this increase points to gratitude’s long-term role in enhancing both cognitive and emotional health.

These changes suggest that gratitude is capable of reshaping neural pathways, reinforcing circuits related to positive thinking and reward processing. Over time, this may alter the way individuals perceive themselves, others, and the world around them, contributing to greater emotional stability and overall happiness (Fox et al., 2015). Additionally, gratitude has been linked with improved immune system functioning through its regulation of neurotransmitters and stress responses, further extending its benefits to physical health (Zahn et al., 2008).

Gratitude, the Brain, and Social Connection: Another critical dimension of gratitude lies in its role in social bonding and connection. Studies highlight a strong relationship between gratitude and oxytocin, the so-called “bonding hormone.” When gratitude is expressed, oxytocin levels rise, promoting trust, empathy, and intimacy within relationships (Algoe & Way, 2014). This demonstrates that gratitude is not merely a private emotional state but a deeply social one that enhances cooperation and strengthens interpersonal ties.

Interestingly, brain activity related to gratitude is not only triggered by personal experiences but also by exposure to stories of compassion and altruism. When people hear narratives about kindness or expressions of gratitude, brain regions associated with empathy and emotional awareness are activated, producing hormonal changes that mirror those experienced when practicing gratitude directly (Algoe & Way, 2014). This suggests that gratitude can spread socially, reinforcing emotional bonds within communities and fostering collective wellbeing.

Consequently, gratitude is a powerful neuropsychological process that affects the brain on multiple levels. It engages moral reasoning centers, regulates the nervous system, activates reward pathways, enhances neurotransmitter release, and even reshapes brain structures. At the same time, it strengthens social bonds by promoting oxytocin release and reinforcing empathy. These findings explain why gratitude is not only a pleasant emotional experience but also a cornerstone of resilience, mental health, and meaningful human connection.

Psychological and Physiological Benefits of Gratitude:

Most people know the warm, uplifting feeling that comes from being appreciated or expressing appreciation to others. Gratitude is more than just a fleeting emotion; it is a powerful psychological and physiological process that links the mind, emotions, and behavior. Recent advances in neuroscience and psychology demonstrate that gratitude can enhance emotional wellbeing, strengthen resilience, improve physical health, and even transform the way the brain responds to stress and adversity.

- Gratitude and Resilience: One of the most consistent findings in gratitude research is its connection to resilience and happiness. Studies have shown that individuals who regularly practice gratitude, such as through journaling, report higher levels of emotional strength and overall happiness (McCanlies et al., 2018). Gratitude shifts attention away from toxic emotions like jealousy, envy, resentment, and anxiety, and instead reinforces focus on positive life experiences. By reframing challenges through appreciation, gratitude builds emotional resilience and equips individuals to handle setbacks more effectively.

- Gratitude as a Buffer Against Stress: Stress reduction is one of gratitude’s most well-documented benefits. Regular practice has been shown to lower cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone, and improve cardiac function, contributing to better heart health (McCraty & Childre, 2004). Participants who practiced gratitude not only reported lower stress levels but also demonstrated greater resilience in the face of emotional setbacks. Moreover, gratitude practices appear to rewire the brain, conditioning it to respond to difficult circumstances with greater awareness, perspective, and emotional balance (McCraty & Childre, 2004).

Spiritual dimensions of gratitude have also been studied. Research indicates that individuals who feel grateful to God tend to report higher stress resilience and better overall health. In one study, older adults who expressed greater gratitude to God scored significantly higher on a stress-tolerance index compared to their peers (Krause, 2006). This suggests that spiritual gratitude may play a unique role in promoting psychological and physiological wellbeing.

- Gratitude and Anxiety: Gratitude has also been linked to reductions in anxiety, particularly when confronting existential fears. In one study, 83 Chinese adults were divided into three groups: one wrote gratitude notes, one wrote about worries, and the third completed a neutral writing task. Afterward, all groups were exposed to stimuli related to death anxiety. Results showed that participants in the gratitude-writing group experienced significantly fewer symptoms of death anxiety compared to the other groups (Lau & Cheng, 2011). These findings highlight gratitude’s ability to foster acceptance and reduce fear of the future, making it a valuable tool in therapeutic and life-coaching interventions.

- Gratitude and Pain Reduction: Gratitude may also alleviate physical pain. By influencing dopamine regulation, gratitude appears to help reduce pain perception and promote more positive affect (Emmons & McCullough, 2003). In their study Counting Blessings Versus Burdens, participants with neuromuscular diseases reported better physical wellbeing when engaging in gratitude practices. Beyond immediate relief, gratitude also increases the likelihood of sustained positive functioning and improved mood over time (Emmons & McCullough, 2003).

- Gratitude and Immunity: The benefits of gratitude extend to the immune system. Individuals with higher levels of trait gratitude report fewer common health complaints, including headaches, digestive issues, infections, dizziness, congestion, and sleep disturbances (Hazlett et al., 2021). Gratitude practices have also been shown to reduce somatic symptoms such as sore muscles, nausea, and fatigue. Researchers suggest that gratitude may work by downregulating threat responses in the amygdala, thereby reducing cellular inflammation linked to poor health outcomes (Hazlett et al., 2021).

- Gratitude and Sleep: Sleep quality is another domain where gratitude demonstrates significant benefits. Neuroscientific research has found that acts of kindness and expressions of gratitude activate the hypothalamus, a brain region that regulates essential bodily functions including sleep cycles (Zahn et al., 2009). When the hypothalamus is stimulated in this way, individuals experience deeper, more restorative sleep and report feeling more energized in the mornings. Gratitude therefore supports both emotional recovery and physical restoration through its impact on sleep regulation.

- Gratitude and Depression: Finally, gratitude plays a protective role against depression. By lowering stress hormones and regulating autonomic nervous system activity, gratitude reduces the intensity of depressive symptoms (Emmons & McCullough, 2003). At the neurochemical level, gratitude enhances activity in the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in managing negative emotions such as guilt, shame, and aggression. Strengthening this neural modulation not only lessens depressive symptoms but also increases empathy, positivity, and prosocial behaviors (Emmons & McCullough, 2003).

In brief, gratitude offers a wide array of psychological and physiological benefits. It builds resilience, lowers stress, reduces anxiety and depression, enhances sleep, improves immunity, and even reduces pain. Through its effects on the brain and body, gratitude functions as a powerful tool for mental health and physical wellbeing, offering a natural and accessible way to promote happiness and resilience across the lifespan.

How to Practice Gratitude for Brain-Boosting Benefits:

Since neuroscience confirms that gratitude can literally reshape the brain, alter cognition, and boost overall wellbeing, the key is to engage in simple practices that cultivate appreciation in daily life. Gratitude does not need to be complicated — even small acts of conscious thankfulness can activate the brain’s reward circuits and reinforce positive emotional patterns. Whether practiced individually or introduced as structured therapeutic interventions, gratitude can unlock what many researchers call a “cognitive superpower.”

1. Appreciate Yourself: The foundation of gratitude begins with the self. Too often, people overlook the importance of acknowledging their own strengths, achievements, and virtues. A simple practice involves standing in front of a mirror and naming five things you genuinely appreciate about yourself. These affirmations can include past accomplishments, current efforts, or enduring qualities such as kindness, loyalty, discipline, or creativity.

Complimenting yourself in this way is more than a confidence booster — it sparks feelings of joy and fosters self-compassion. Over time, practicing self-directed gratitude helps individuals develop a healthier self-image and a stronger sense of resilience when facing life’s challenges.

2. Keep a Gratitude Journal: One of the most effective tools for cultivating gratitude is a gratitude journal. This practice creates a dedicated space to record the people, events, and circumstances that bring meaning and joy to life. The act of writing itself forces the brain to consciously shift focus away from negativity and toward appreciation, strengthening positive thinking habits over time.

To maximize benefits, experts recommend several tips for gratitude journaling:

- Be specific in your entries rather than vague.

- Provide depth and detail, exploring why you are grateful for a particular experience or person.

- Write regularly and consistently to build a habit.

- Reflect not only on positive gifts but also on negative experiences that were avoided or resolved, acknowledging growth and resilience.

- Savor the emotions that arise during reflection, allowing gratitude to be felt fully rather than just recorded.

With consistent practice, gratitude journals become powerful reminders of life’s blessings and sources of comfort during difficult times.

3. Gratitude Visits: Expressing gratitude toward others magnifies its effects. A particularly impactful method is the gratitude visit. This involves writing a heartfelt letter to someone who has made a meaningful difference in your life, then personally delivering it and reading it aloud to the recipient.

Research shows that gratitude visits foster profound emotional experiences for both the giver and the receiver, producing lasting improvements in wellbeing, happiness, and social connection. Participants report feeling more purposeful, more connected to others, and more satisfied with life following such visits (Stefan et al., 2021). Unlike fleeting compliments, gratitude visits create memorable moments of authentic appreciation that strengthen bonds and reinforce positive emotions.

4. Gratitude Meditation and Exercises: Another powerful way to integrate gratitude into daily life is through meditation and structured exercises. Gratitude meditation typically involves pausing, being present, and reflecting intentionally on specific people, circumstances, or aspects of life for which one feels thankful. This can be practiced for a few minutes daily or incorporated into existing meditation routines.

Interestingly, research suggests that even a single session of gratitude meditation can produce noticeable psychological benefits, including reduced stress and improved mood. Over time, the practice deepens emotional awareness, enhances empathy, and fosters a greater sense of peace.

Beyond meditation, a wide range of gratitude exercises exist, many of which can be incorporated into therapy and coaching sessions. These may include guided reflections, group discussions, or structured “homework” assignments where clients practice gratitude in specific contexts. Such interventions not only strengthen individual mental health but also encourage stronger interpersonal relationships and a more compassionate outlook on life.

Eventually, gratitude can be practiced in many forms — from private reflections in a journal to shared experiences like gratitude visits or meditations. Each of these practices stimulates the brain’s reward pathways, enhances emotional resilience, and builds stronger social bonds. By weaving gratitude into daily routines, individuals can experience its brain-boosting benefits while cultivating a more positive, purposeful, and fulfilling life (Stefan et al., 2021).

How Helping Professionals Can Use Gratitude in Therapy and Coaching:

Gratitude is not only a personal practice but also a valuable therapeutic tool. Helping professionals, such as therapists, counselors, and coaches, can integrate gratitude into their sessions in both direct and subtle ways. By encouraging clients to cultivate a mindset of appreciation, practitioners can help them tap into the neurobiological and psychological benefits of gratitude, which include reduced stress, improved resilience, and greater overall wellbeing.

Starting with Awareness: One of the simplest ways to introduce gratitude into therapy is by cultivating awareness and presence. For example, sessions can begin with a brief body scan or a few minutes of mindful breathing to ground the client. Once settled, the practitioner can ask the client to reflect on one thing they felt grateful for since the previous meeting. This simple exercise shifts attention away from stressors and toward positive experiences, setting a constructive tone for the session.

Teaching clients to live with greater awareness of gratitude can activate the neurobiological benefits described in the literature, such as regulating stress responses, enhancing mood, and strengthening emotional resilience (McCraty & Childre, 2004). Over time, this practice not only improves mental health but also reshapes how clients view their lives and relationships.

Three Practical Approaches for Professionals:

- Visual Reminders of Gratitude: Encourage clients to create visual cues that remind them to be grateful in their everyday lives. These may include affirmations placed on mirrors, photographs of loved ones, images of meaningful places, or notes highlighting personal achievements and milestones. Such reminders help anchor gratitude in daily routines, making it more than a fleeting thought and transforming it into a sustainable habit.

- Reinforcing Grateful Language: Language plays a powerful role in shaping thought patterns. Research shows that individuals who practice gratitude often use words such as gifts, blessings, fortunate, abundance, and givers (McCraty & Childre, 2004). By reinforcing this type of language during sessions, therapists and coaches can help clients reframe challenges and adopt a more appreciative outlook. Encouraging clients to discuss their lives using terms of abundance rather than deficit strengthens both the practice and the mindset of gratitude.

- Structured Gratitude Exercises: Incorporating gratitude-based exercises into therapy or coaching can be highly effective in addressing specific issues. Techniques such as journaling about things one is grateful for, writing thank-you notes, or engaging in gratitude meditations can be used to build resilience, reduce negative emotions, and improve relationships. These practices not only foster self-awareness but also help clients experience gratitude’s social and emotional benefits firsthand.

Subsequently, gratitude can be seamlessly woven into therapeutic and coaching practices — whether through mindful reflection, positive language, visual cues, or structured exercises. Helping clients cultivate gratitude allows them to access its profound psychological and physiological benefits, while also strengthening coping skills, enhancing resilience, and promoting healthier relationships (McCraty & Childre, 2004).

The Future of Gratitude Research in Neuroscience:

The scientific exploration of gratitude is still in its early stages, yet the findings so far have been both compelling and transformative. Current evidence clearly demonstrates that gratitude is more than an abstract feeling — it is an emotion with direct and measurable effects on both the brain and the body (Hazlett et al., 2021). As neuroscience advances, researchers are beginning to envision new ways of studying and even enhancing gratitude, potentially unlocking deeper insights into its therapeutic and health-related benefits.

Integrating Technology with Gratitude Research: Future studies are likely to merge gratitude research with cutting-edge developments in neurotechnology, brain–computer interfaces, artificial intelligence, and neurostimulation. These tools may allow scientists to map the neural pathways of gratitude with unprecedented precision, shedding light on how gratitude interacts with networks related to reward, emotion regulation, and social bonding. Beyond observation, neurostimulation techniques could potentially be used to amplify the brain’s natural capacity for gratitude, making it easier for individuals to access the positive emotions and physiological benefits associated with this state.

Artificial intelligence, in particular, holds promise for analyzing large datasets from gratitude interventions, identifying patterns across diverse populations, and even personalizing strategies for cultivating gratitude. For example, AI-driven applications may one day be used in therapy or coaching to recommend customized gratitude practices based on individual brain responses, emotional profiles, or health conditions.

Long-Term Effects and Practical Applications: Another important direction for future research lies in exploring the long-term effects of gratitude. While short-term benefits — such as reduced stress, improved mood, and better sleep — are well-documented, less is known about how sustained gratitude practice might influence the brain and body over years or even decades. Understanding these long-term effects could be particularly valuable for therapists, counselors, and coaches who seek to integrate gratitude into structured treatment plans.

By studying how consistent gratitude practices reshape brain structures, regulate stress hormones, and enhance resilience, researchers could help professionals design evidence-based interventions tailored to specific populations. For example, gratitude-based therapies may be adapted for individuals struggling with anxiety, trauma, or chronic illness, offering a low-cost, accessible, and non-invasive complement to traditional treatments.

Ultimately, the future of gratitude research in neuroscience lies at the intersection of psychology, technology, and clinical application. With advancements in neurotechnology and AI, it may soon be possible not only to better understand the neural mechanisms of gratitude but also to enhance and sustain it in ways that optimize mental, emotional, and physical health. This next phase of research promises to provide therapists, coaches, and healthcare professionals with powerful new tools to harness gratitude’s full potential for human wellbeing (Hazlett et al., 2021).

At the end of the day, we can say that the neuroscience of gratitude reminds us that appreciation is not just a pleasant emotion but a transformative force with tangible effects on the brain, body, and spirit. By consciously practicing gratitude—whether through kind words, reflective journaling, or simply pausing to notice life’s blessings—we nurture stronger relationships, greater resilience, and a deeper sense of wellbeing. Gratitude gives us a way to reframe challenges, celebrate small victories, and approach each day with renewed hope. In essence, it is both a science-backed practice and a timeless human strength that allows us to live more connected, meaningful, and fulfilling lives.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

How does gratitude change the brain?

Gratitude activates neural circuits involved in reward, empathy, and emotional regulation. When we practice gratitude, areas such as the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex show increased activity, which helps with decision-making, emotional balance, and positive social behaviors. Over time, regular gratitude practices can strengthen these pathways, making it easier to focus on positive experiences and regulate stress.

What are the neurological benefits of gratitude?

The neurological benefits include increased dopamine and serotonin production, which improve mood, as well as reduced activity in the amygdala, which lowers stress and anxiety. Gratitude also supports healthier sleep, boosts resilience, and contributes to long-term wellbeing by reinforcing positive thought patterns.

Which part of the brain is more active when we feel gratitude?

Research shows that gratitude activates several regions of the brain, particularly the medial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and ventral striatum. These areas are associated with reward processing, empathy, and moral cognition, explaining why gratitude enhances both personal happiness and social connection.

Can gratitude practice actually change brain structure?

Yes, studies using brain imaging have found that consistent gratitude practices can increase gray matter volume in regions associated with emotional regulation and learning. This suggests that gratitude not only changes brain function but may also lead to structural changes over time.

How does gratitude affect stress and anxiety?

Gratitude reduces the body’s stress response by calming the sympathetic nervous system. It lowers cortisol levels, helps regulate heart rate, and increases activity in brain regions that counterbalance fear and worry. This makes gratitude a valuable tool for managing anxiety and building resilience.

Does gratitude improve relationships?

Absolutely, expressing gratitude activates brain regions linked to social bonding and empathy, often accompanied by oxytocin release—the hormone connected to trust and closeness. This strengthens relationships, increases feelings of safety, and fosters deeper connections.

Can gratitude be used in therapy?

Yes, Therapists and coaches often incorporate gratitude practices such as journaling, gratitude visits, or mindfulness exercises. These practices can help clients reframe negative experiences, reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, and improve overall mental health outcomes.

How quickly can someone feel the benefits of gratitude?

Some people notice benefits after a single session of gratitude meditation or journaling, such as feeling calmer or more optimistic. However, long-term, consistent practice is where the biggest changes occur—both in how the brain functions and in overall wellbeing.

References:

- Algoe, S. & Way, B. (2014). Evidence for a role of the oxytocin system, indexed by genetic variation in the social bonding effects of expressed gratitude. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(12), 1855–1861. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst182

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377

- Emmons, R. & McCullough, M. (2004). The psychology of gratitude (series in affective science). Oxford University Press.

- Fox, G. R., Kaplan, J., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. (2015). Neural correlates of gratitude. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 1491, 149–154. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01491

- Hazlett, L., Moieni, M., Irwin, M., Haltom, K., Jevtic, I., Meyer, M., Breen, E., Cole, S. & Eisenberger, N. (2021). Exploring neural mechanisms of the health benefits of gratitude in women: A randomized controlled trial. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 95, 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.04.019

- Krause, N. (2006). Gratitude toward God, stress and health in late life. Research on Aging, 28(2), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027505284048

- Lau, R. W. & Cheng, S. T. (2011). Gratitude lessens death anxiety. European Journal of Aging, 8(3), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-011-0195-3

- McCanlies, C., Gu, K., Andrew, E. & Violanti, M. (2018). The effect of social support, gratitude, resilience and satisfaction with life on depressive symptoms among police officers following Hurricane Katrina. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 64(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764017746197

- McCraty, R. & Childre, D. (2004). The grateful heart: The psychophysiology of appreciation. In R. Emmons & E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 230–255). Oxford University Press.

- Russell, E. & Fosha, D. (2008). Transformational affects and core state in AEDP: The emergence and consolidation of joy, hope, gratitude and confidence in (the solid goodness of) the self. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 18(2), 167–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/1053-0479.18.2.167

- Stefan, D., Lefdahl, E., Alayan, A., Decker, M., Kulwicki, T., Parallel, J. & Wittwer, J. (2021). The impact of gratitude letters and visits on relationships, happiness, wellbeing and meaning in graduate students. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 5(2), 110–126. Retrieved From https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d1b5/f198239ccbc89297dea8c6303f94b2c51151.pdf

- Wong, Y., Owen, J., Gabana, N., Brown, J., McInnis, S., Toth, P. & Gilman, L. (2018). Does gratitude writing improve the mental health of psychotherapy clients? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 28(2), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1169332

- Zahn, R., Garrido, G., Moll, J. & Grafman, J. (2014). Individual differences in posterior cortical volume correlate with proneness to pride and gratitude. Social Cognition and Affective Neuroscience, 9(11), 1676–1683. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst158

- Zahn, R., Moll, J., Iyengar, V., Huey, E., Tierney, M., Krueger, F. & Grafman, J. (2009). Social conceptual impairments in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with right anterior temporal hypometabolism. Brain, 132(3), 604–616. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awn343

- Zahn, R., Moll, J., Paiva, M., Garrido, G., Krueger, F. & Huey, E. (2008). The neural basis of human social values: Evidence from functional MRI. Cerebral Cortex, 19(2), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn080

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College