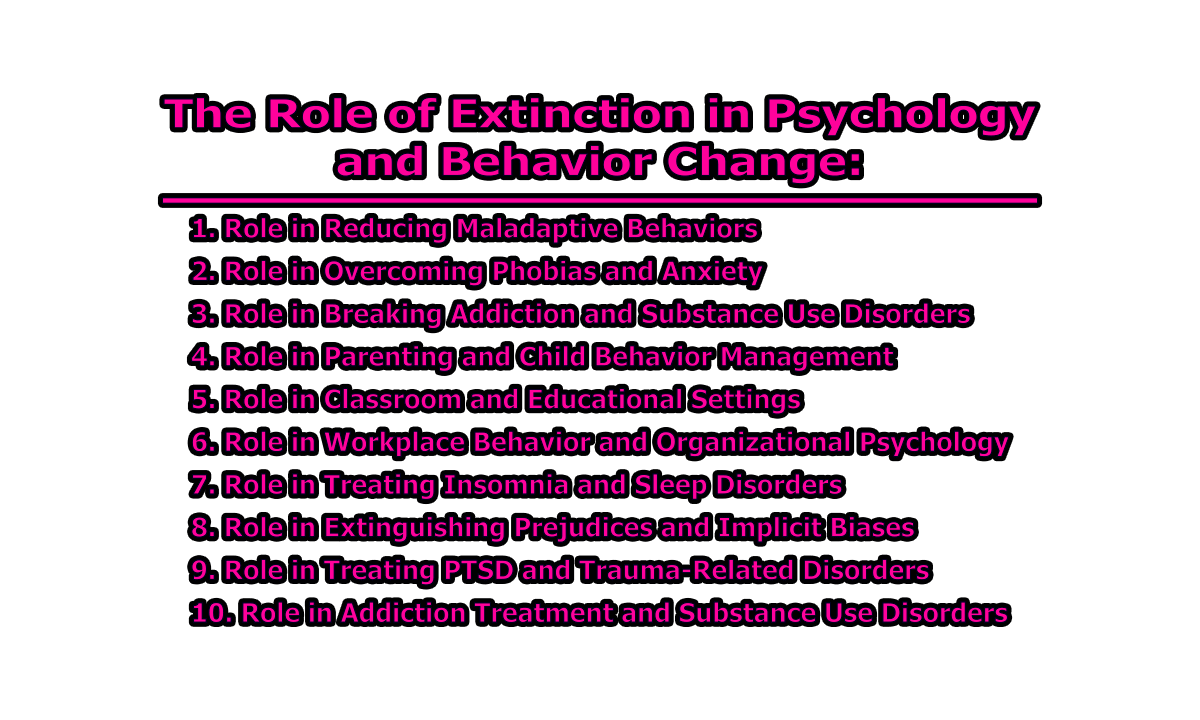

The Role of Extinction in Psychology and Behavior Change:

Extinction is a fundamental concept in behavioral psychology that refers to the gradual weakening and disappearance of a learned response when reinforcement is removed (Skinner, 1953). It plays a vital role in modifying behaviors across various domains, including education, therapy, addiction treatment, and workplace management. This article explores the role of extinction in psychology and behavior change.

1. Role in Reducing Maladaptive Behaviors: Extinction is a core principle used in applied behavior analysis (ABA) to reduce maladaptive behaviors, such as self-injury, aggression, or compulsive actions (Iwata et al., 1994). Maladaptive behaviors are often reinforced by external factors, such as attention, access to a desired item, or escape from a demand (Lerman & Iwata, 1996). When the reinforcement is consistently removed, the behavior eventually diminishes.

For example, if a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) frequently engages in self-injurious behavior (SIB), such as head-banging, to gain attention, behavior analysts might implement an extinction procedure by withholding attention when the behavior occurs (Hagopian et al., 1998). Instead, reinforcement (such as praise or tangible rewards) is provided for appropriate behaviors like using words or gestures to communicate needs.

However, extinction alone is often not enough. It is typically combined with differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA) to teach more adaptive behaviors (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2020). Without a suitable replacement behavior, extinction may lead to extinction bursts, where the behavior temporarily increases in frequency and intensity before declining (Lerman & Iwata, 1995). Therefore, extinction procedures must be applied carefully to prevent frustration and aggression.

2. Role in Overcoming Phobias and Anxiety: Extinction is a key mechanism in exposure therapy, a treatment for phobias, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Bouton, 2004). In classical conditioning, fear responses are learned when a previously neutral stimulus (e.g., a dog) is paired with a negative experience (e.g., being bitten), leading to a conditioned fear response (Pavlov, 1927). Extinction occurs when the feared stimulus is repeatedly presented without negative consequences, weakening the conditioned fear response over time (Myers & Davis, 2007).

For instance, in systematic desensitization, a person with arachnophobia (fear of spiders) might first be shown pictures of spiders, then watch videos, and eventually encounter a real spider in a controlled environment. Over repeated exposures, without any harm occurring, the conditioned fear response gradually weakens and extinguishes (Craske et al., 2014).

However, extinction is not always permanent. Spontaneous recovery can occur, where the fear response temporarily returns after a rest period (Rescorla, 2004). To strengthen extinction, contextual learning is emphasized—patients practice exposure in multiple environments to ensure long-term success (Vervliet, Craske, & Hermans, 2013).

3. Role in Breaking Addiction and Substance Use Disorders: Extinction is also used in substance abuse treatment, particularly in cue-exposure therapy (CET), where drug-related cues (e.g., seeing a syringe or smelling alcohol) are repeatedly presented without the actual drug, weakening the association between cues and cravings (Millan et al., 2011). This approach is based on classical conditioning, where drug users develop conditioned responses to environmental triggers (Conklin & Tiffany, 2002).

For example, a recovering smoker may experience intense cravings when seeing a cigarette pack or smelling tobacco smoke. In CET, the smoker is repeatedly exposed to these cues without being allowed to smoke, leading to extinction of the craving response (McHugh et al., 2010).

However, relapse remains a major challenge because:

- Spontaneous recovery – cravings may re-emerge unexpectedly after extinction (Bouton, 2002).

- Renewal effect – cravings can return if the person encounters a different setting (e.g., returning to an old neighborhood) (Crombag & Shaham, 2002).

- Reinstatement – a single exposure to the drug can reactivate cravings (Kalivas & O’Brien, 2008).

To improve long-term outcomes, extinction-based therapies are often combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), pharmacological treatments (e.g., naltrexone for opioid addiction), and mindfulness techniques.

4. Role in Parenting and Child Behavior Management: Extinction is widely used in parenting and child behavior management to decrease undesirable behaviors, especially those maintained by attention (Patterson, 1982). Parents often unintentionally reinforce behaviors like tantrums, whining, or excessive demands by responding to them with attention, even if it’s negative (e.g., scolding or arguing). When parents withhold reinforcement—by ignoring the behavior—it gradually decreases (Reiber et al., 2004).

A classic example is the extinction of bedtime tantrums. If a child cries every night to avoid sleeping alone, parents may unknowingly reinforce this by comforting the child or allowing co-sleeping. Implementing extinction involves consistently ignoring the tantrums while reinforcing independent sleeping behaviors, such as praising the child for staying in bed (Mindell et al., 2006).

However, extinction bursts—temporary intensifications of the unwanted behavior—are common (Lerman & Iwata, 1995). If parents give in during this phase, the behavior becomes even more resistant to extinction. To increase effectiveness, extinction should be paired with reinforcement of alternative behaviors (e.g., rewarding calm bedtime routines).

Challenges and Ethical Considerations:

- Gradual withdrawal is often recommended to reduce distress, especially in infants and young children (France & Hudson, 1990).

- Parental consistency is key—if caregivers occasionally reinforce the behavior, extinction may fail (Wakschlag et al., 2005).

- Cultural differences exist—some parenting styles prioritize responsiveness over extinction-based methods (Sadeh et al., 2010).

5. Role in Classroom and Educational Settings: Teachers use extinction techniques in classroom management to reduce disruptive behaviors while reinforcing positive behaviors (Reiber & McLaughlin, 2004). In many cases, students act out to gain attention from teachers or peers. If a teacher consistently ignores off-task behavior (e.g., calling out without raising a hand) while only responding to rule-following behaviors, the undesired behavior decreases over time (Simonsen, Fairbanks, Briesch, Myers, & Sugai, 2008).

For example, if a student frequently interrupts lessons by making jokes, and the teacher stops reacting (while reinforcing appropriate participation), the behavior weakens due to lack of reinforcement (Scott et al., 2001).

Extinction Strategies in Education:

- Planned Ignoring: Used for attention-seeking behaviors like excessive talking or whining (Allday & Pakurar, 2007).

- Token Systems: Extinction is often combined with positive reinforcement, where students earn points or rewards for following rules (Ayllon & Roberts, 1974).

- Peer Influence: Ignoring disruptive behavior works best when peers also withhold reinforcement (Wright & McCurdy, 2012).

Challenges in Classroom Extinction:

- Extinction bursts: Initially, disruptive behavior may increase before it declines. Teachers must remain consistent to avoid reinforcing escalation (Lerman et al., 1999).

- Emotional side effects: Frustrated students may exhibit aggression when reinforcement is removed. Teachers should provide alternative coping strategies (McCurdy et al., 2003).

- Effectiveness depends on function: Extinction is less effective if a behavior is reinforced by automatic reinforcement (e.g., sensory stimulation) rather than attention (Iwata et al., 1994).

6. Role in Workplace Behavior and Organizational Psychology: Extinction principles are used in workplace behavior management to shape employee productivity and reduce counterproductive work behaviors (Daniels, 2000). If a behavior (e.g., frequent lateness or excessive socializing) is no longer rewarded, it gradually decreases.

For example, if employees frequently take extended breaks, and supervisors stop allowing extra time without consequences, employees learn that this behavior is no longer reinforced and reduce it (Geller, 2005).

Applications in Workplace Behavior:

- Performance-Based Incentives: If employees no longer receive bonuses for meeting sales quotas, their motivation may decrease (Stajkovic & Luthans, 2006).

- Reducing Unproductive Meetings: If managers ignore off-topic discussions during meetings, employees eventually stick to relevant topics (Komaki, 1998).

- Discouraging Workplace Complaints: If complaints no longer receive attention, employees may find alternative solutions rather than relying on supervisors (Luthans & Kreitner, 1985).

Challenges in Workplace Extinction:

- Resistance to Change: Employees accustomed to rewards may resist extinction-based changes, leading to temporary declines in morale (Geller, 2005).

- Risk of Burnout: If positive reinforcement is also removed, employees may feel undervalued, reducing job satisfaction (Deci et al., 1999).

- Cultural Sensitivity: In some workplaces, ignoring behaviors may be perceived as disrespectful rather than a behavior modification strategy (Hofstede, 2001).

Best Practices for Workplace Extinction:

- Pair extinction with reinforcement: Encourage alternative productive behaviors (e.g., rewarding employees for timeliness rather than punishing lateness) (Daniels, 2000).

- Provide feedback and support: Help employees adjust rather than abruptly removing reinforcement (Stajkovic & Luthans, 2003).

7. Role in Treating Insomnia and Sleep Disorders: Extinction plays a crucial role in treating sleep-related issues, particularly insomnia and behavioral sleep disorders in children. Many sleep disturbances are maintained by reinforcement from caregivers or environmental cues (Mindell et al., 2006).

For example, sleep-onset association disorder occurs when a child relies on external cues (e.g., parental presence, rocking, or feeding) to fall asleep (France & Hudson, 1990). If caregivers consistently provide these cues, the child fails to develop independent sleep skills. Extinction therapy involves gradually removing these reinforcers, allowing the child to learn self-soothing behaviors.

Extinction-Based Sleep Interventions:

- Graduated Extinction (Ferber Method): Parents progressively delay responding to night wakings, reducing reinforcement while still providing periodic comfort (Ferber, 1985).

- Unmodified Extinction (Cry-It-Out Method): Parents completely ignore night wakings, leading to eventual extinction of excessive crying (Mindell et al., 2006).

- Extinction with Parental Presence: Parents remain in the room but avoid providing reinforcement, reducing distress while promoting self-soothing (Sadeh et al., 2010).

Challenges and Ethical Considerations:

- Extinction bursts: Initial increases in crying or protesting may distress both children and parents (France & Blampied, 1999).

- Parental Consistency is Key: Intermittent reinforcement (e.g., responding to crying some nights but not others) can strengthen the behavior instead of extinguishing it (Blunden, 2011).

- Cultural Sensitivity: Some cultures emphasize co-sleeping and responsive parenting, making extinction-based sleep training less acceptable (Sadeh, 2004).

Overall, extinction-based sleep training is effective for most children, with studies showing significant reductions in night wakings and sleep latency (Mindell et al., 2006). However, it should be customized based on child temperament and parental preferences.

8. Role in Extinguishing Prejudices and Implicit Biases: Extinction principles are also applied in social psychology, particularly in reducing stereotypes, prejudices, and implicit biases. Prejudice and bias are often conditioned responses—learned through repeated exposure to negative associations between certain groups and negative traits (Devine, 1989).

For example, if a person associates a particular racial or social group with negative stereotypes, their automatic bias is reinforced by media portrayals, social interactions, and cultural influences (Dovidio et al., 2001). Extinction techniques aim to disrupt these associations by exposing individuals to counter-stereotypical information without reinforcing the original bias (Gawronski et al., 2008).

Extinction Strategies for Reducing Bias:

- Counterconditioning: Individuals are exposed to positive exemplars (e.g., successful figures from stigmatized groups) to replace negative associations (Dasgupta & Greenwald, 2001).

- Repeated Exposure: Intergroup contact reduces bias by weakening conditioned stereotypes (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006).

- Implicit Bias Training: Cognitive interventions focus on consciously unlearning implicit biases through controlled exposure to counter-stereotypes (Devine et al., 2012).

Challenges in Bias Extinction:

- Spontaneous Recovery: Biases can return if an individual encounters a stereotype-reinforcing environment (Gawronski & Cesario, 2013).

- Renewal Effect: Bias extinction may be context-specific—someone may show reduced bias in a controlled setting but revert in real-world situations (Dasgupta, 2013).

- Motivational Barriers: Extinction of prejudice requires conscious effort, making it less effective in individuals who resist change (Plant & Devine, 2009).

Despite these challenges, research suggests that structured interventions can effectively weaken implicit biases over time, making extinction a valuable tool in diversity training and prejudice reduction (Devine et al., 2012).

9. Role in Treating PTSD and Trauma-Related Disorders: Extinction-based therapies are critical in treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other trauma-related conditions. PTSD develops when a traumatic event leads to conditioned fear responses, where neutral stimuli (e.g., loud noises, crowded places) become associated with trauma (Myers & Davis, 2007).

Extinction therapy helps by breaking these associations through exposure-based interventions, where patients repeatedly confront trauma-related cues in a safe environment until the fear response diminishes (Briggs & McMullen, 2024).

Extinction-Based PTSD Treatments:

- Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE): Patients repeatedly recount traumatic experiences and confront trauma-related cues to facilitate extinction (Foa et al., 2007).

- Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET): Uses immersive environments to expose PTSD patients (e.g., war veterans) to trauma-related cues in a controlled setting (Rizzo et al., 2010).

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): Uses guided exposure with bilateral stimulation (e.g., eye movements) to weaken trauma associations (Shapiro, 2001).

Challenges in PTSD Extinction:

- Extinction Doesn’t Erase Memory: Trauma-related associations may weaken but can reappear under stress (Milad et al., 2006).

- Avoidance Behaviors Hinder Treatment: Many patients avoid exposure therapy, preventing extinction from occurring (Craske et al., 2014).

- Context-Specific Extinction: Extinction may not generalize across environments, requiring diverse exposure settings (Vervliet et al., 2013).

Despite these challenges, extinction-based therapies are among the most effective treatments for PTSD, with long-term symptom reduction in most patients (Powers et al., 2010).

10. Role in Addiction Treatment and Substance Use Disorders: Extinction plays an essential role in addiction treatment by weakening the associations between drug-related cues and cravings (Bouton, 2002). Substance use disorders (SUDs) are partially driven by conditioned responses, where environmental cues (e.g., places, people, paraphernalia) trigger cravings and compulsive drug-seeking behavior (Everitt & Robbins, 2005).

For example, a person recovering from alcohol addiction may experience cravings when walking past a bar because past reinforcement (e.g., drinking in that setting) has conditioned an automatic response. Extinction-based therapies focus on breaking these associations through repeated exposure to these cues without drug reinforcement, gradually weakening cravings (Conklin & Tiffany, 2002).

Extinction-Based Addiction Treatments:

- Cue Exposure Therapy (CET): Individuals are exposed to drug-related cues (e.g., seeing a cigarette, holding a beer bottle) without actual substance use, leading to extinction of cravings (Childress et al., 1993).

- Virtual Reality Cue Exposure: A newer method using immersive digital environments to expose patients to realistic drug-related cues in a safe setting (Pericot-Valverde et al., 2012).

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT incorporates extinction principles by encouraging patients to challenge cravings and avoid reinforcing relapse behaviors (Marlatt & Donovan, 2005).

Challenges in Addiction Extinction:

- Spontaneous Recovery: Cravings may resurface unexpectedly, especially under stress (Bouton, 2002).

- Renewal Effect: Extinction often occurs in controlled therapy settings, but drug-seeking behavior may return in real-life environments (Conklin & Tiffany, 2002).

- High Relapse Rates: Without reinforcement of alternative coping strategies, extinction alone may be insufficient (Everitt & Robbins, 2005).

Best Practices for Addiction Extinction:

- Combine extinction with reinforcement: Reward healthy coping mechanisms, such as exercise or mindfulness, to replace substance use (Higgins et al., 1994).

- Train in multiple settings: Extinction should occur in varied environments to prevent context-dependent relapse (Bouton, 2004).

- Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT): Drugs like naltrexone and buprenorphine help reduce cravings by interfering with reinforcement mechanisms (Volkow et al., 2016).

Despite challenges, extinction-based interventions have shown significant success in reducing substance use and preventing relapse, especially when combined with behavioral reinforcement strategies (Conklin & Tiffany, 2002).

At the end of the day, we can say that extinction is a fundamental psychological process that plays a fundamental role in modifying behavior, unlearning conditioned responses, and facilitating long-term change. From treating phobias and PTSD to managing addiction and reinforcing positive behaviors, extinction-based techniques are widely applied in therapy, education, and behavioral interventions. However, extinction is not always permanent, as behaviors can resurface due to spontaneous recovery, renewal effects, and relapse. To maximize effectiveness, extinction should be combined with reinforcement strategies, exposure across multiple contexts, and cognitive-behavioral interventions. Understanding extinction not only enhances therapeutic outcomes but also helps individuals adapt to new behaviors, overcome maladaptive habits, and improve emotional regulation in daily life.

References:

- Allday, R. A., & Pakurar, K. (2007). Effects of teacher greetings on student on-task behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(2), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2007.86-06

- Ayllon, T., & Roberts, M. D. (1974). Eliminating discipline problems by strengthening academic performance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 7(1), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1974.7-71

- Bouton, M. E. (2002). Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: Sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biological Psychiatry, 52(10), 976–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01546-9

- Bouton, M. E. (2004). Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning & Memory, 11(5), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.78804

- Briggs JF, McMullen KM. Retrograde amnesia for the stress-induced impairment of extinction: time-dependent and not so forgotten. Learn Mem. 2024 Jan 29;31(1-2):a053895. doi: 10.1101/lm.053895.123. PMID: 38286522; PMCID: PMC10903941.

- Childress, A. R., McLellan, A. T., & O’Brien, C. P. (1986). Abstinent opiate abusers exhibit conditioned craving, conditioned withdrawal and reductions in both through extinction. British Journal of Addiction, 81(5), 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00385.x

- Conklin, C. A., & Tiffany, S. T. (2002). Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction, 97(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x

- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson.

- Craske, M. G., Treanor, M., Conway, C. C., Zbozinek, T., & Vervliet, B. (2014). Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 10-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006

- Crombag, H. S., & Shaham, Y. (2002). Renewal of drug seeking by contextual cues after prolonged extinction in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience, 116(1), 169–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7044.116.1.169

- Dasgupta, N. (2013). Implicit attitudes and beliefs adapt to social context. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 233-331. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00005-X

- Daniels, A. C. (2000). Bringing out the best in people: How to apply the astonishing power of positive reinforcement. McGraw-Hill.

- Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

- Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5

- Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit bias. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267-1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003

- Everitt, B. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2005). Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: gFrom actions to habits to compulsion. Nature Neuroscience, 8(11), 1481–1489. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1579

- Ferber, R. (1985). Solve your child’s sleep problems. Simon & Schuster.

- Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2007). Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences. Oxford University Press.

- France, K. G., & Hudson, S. M. (1990). Behavior management of infant sleep disturbance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23(1), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1990.23-91

- Gawronski, B., & Cesario, J. (2013). Of mice and men: What animal research can tell us about context effects on automatic responses in humans. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(2), 187-215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868313480096

- Geller, E. S. (2005). People-based safety: The source. Coastal Training Technologies.

- Hagopian, L. P., Fisher, W. W., Sullivan, M. T., Acquisto, J., & LeBlanc, L. A. (1998). Effectiveness of functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment: a summary of 21 inpatient cases. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31(3), 345-368. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1998.31-211

- Higgins, S. T., Wong, C. J., Badger, G. J., Ogden, D. E., & Dantona, R. L. (2000). Contingent reinforcement increases cocaine abstinence during outpatient treatment and 1 year of follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.64

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Sage.

- Iwata, B. A., Pace, G. M., Cowdery, G. E., & Miltenberger, R. G. (1994). What makes extinction work: An analysis of procedural form and function. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(1), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1994.27-131

- Kalivas, P. W., & O’Brien, C. (2008). Drug addiction as a pathology of staged neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(1), 166-180. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301564

- Komaki, J. (1998). Leadership from an operant perspective. Routledge.

- Leitenberg, H., Rawson, R. A., & Mulick, J. A. (1975). Extinction and reinforcement of alternative behavior. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 88(2), 640–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076418

- Lerman, D. C., & Iwata, B. A. (1995). Prevalence of the extinction burst and its attenuation during treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28(1), 93–94. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1995.28-93

- Luthans, F., & Kreitner, R. (1985). Organizational behavior modification and beyond: An operant and social learning approach. Scott, Foresman.

- Marlatt, G. A., & Donovan, D. M. (Eds.). (2005). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- McHugh, R. K., Hearon, B. A., & Otto, M. W. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 33(3), 511–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.012

- Milad, M. R., & Norrholm, S. D. (2023). Fear extinction: From basic neuroscience to clinical implications. Springer International Publishing.

- Millan EZ, Marchant NJ, McNally GP. Extinction of drug seeking. Behav Brain Res. 2011 Mar 1;217(2):454-62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.10.037. Epub 2010 Nov 10. PMID: 21073904.

- Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, Meltzer LJ, Sadeh A; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006 Oct;29(10):1263-76. Erratum in: Sleep. 2006 Nov 1;29(11):1380. PMID: 17068979.

- Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process. Castalia Publishing.

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Oxford University Press.

- Pericot-Valverde I, García-Rodríguez O, Ferrer-García M, Secades-Villa R, Gutiérrez-Maldonado J. Virtual reality for smoking cessation: a case report. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;181:292-6. PMID: 22954874.

- Powers, M. B., Halpern, J. M., Ferenschak, M. P., Gillihan, S. J., & Foa, E. B. (2010). A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for PTSD. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(6), 635-641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.007

- Reiber, Christopher, & McLaughlin, T. F. (2004). Classroom Interventions: Methods to Improve Academic Performance and Classroom Behavior for Students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. International Journal of Special Education, 19(1); p1-13. ERIC Number: EJ852038; ISSN: ISSN-0827-3383.

- Rescorla, R. A. (2004). Spontaneous recovery. Learning & Memory, 11(5), 501-509.

- Rothbaum, B. O., & Davis, M. (2003). Applying learning principles to PTSD. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1008, 112-121. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1301.012

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Simon and Schuster.

- Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (2006). Behavioral management and task performance in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 46(3), 325-334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00147.x

- Sutton, R. S., & Barto, A. G. (2018). Reinforcement learning: An introduction. MIT Press.

- Todd, T. P., Vurbic, D., & Bouton, M. E. (2014). Behavioral and neurobiological mechanisms of extinction in Pavlovian and instrumental learning. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 108, 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2013.08.012

- Vervliet, B., Craske, M. G., & Hermans, D. (2013). Fear extinction and relapse. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 9; 215-48. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185542

- Volkow, N. D., Koob, G. F., & McLellan, A. T. (2016). Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(4), 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1511480

- Wood, W., & Rünger, D. (2016). Psychology of habit. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 289-314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College