Basic Understanding of Cognitive Restructuring:

In everyday life, our minds rarely pause before drawing conclusions. Thoughts arise automatically, often shaped by past experiences, assumptions, and deeply ingrained patterns of interpretation. While these mental shortcuts can help us navigate the world efficiently, they can also lead us toward distorted or overly negative conclusions without our conscious awareness. This is where cognitive restructuring, a core technique of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), becomes especially valuable. Cognitive restructuring is the process of identifying, challenging, and reshaping unhelpful thought patterns that contribute to emotional distress. Rather than accepting every thought as fact, it teaches individuals to examine the evidence behind their beliefs, recognize cognitive distortions such as catastrophizing or all-or-nothing thinking, and replace them with more balanced, realistic perspectives. By learning to interrupt automatic negative thought cycles, individuals can improve emotional resilience, enhance well-being, and respond to life’s challenges with greater clarity and confidence. In the rest of this article, we will explore the basic understanding of cognitive restructuring.

What Is Cognitive Restructuring?

Cognitive restructuring (also referred to as cognitive reframing) is a structured psychological process designed to help individuals identify, challenge, and replace maladaptive patterns of thinking. Rooted in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), it focuses on uncovering automatic negative thoughts and deeply held beliefs that shape emotional responses and behaviors. According to Clark (2013), cognitive restructuring helps clients discover, evaluate, and modify irrational or distorted thoughts that contribute to distress. Rather than attempting to suppress thoughts, the process encourages individuals to examine them critically and replace them with more balanced and evidence-based interpretations.

As a foundational technique in CBT, cognitive restructuring is widely used because many psychological difficulties are maintained not merely by external events, but by how individuals interpret those events (Mills et al., 2008). For example, two people may experience the same setback (such as failing an exam) but respond very differently depending on their thought patterns. One may think, “I failed this test; I’m stupid,” while another may think, “I didn’t prepare effectively this time; I can improve.” The event is identical, but the interpretation determines the emotional outcome.

Mills et al. (2008) emphasize that cognitive restructuring reduces stress by cultivating more adaptive thinking habits and strengthening constructive self-talk. Over time, replacing harsh self-criticism with realistic and compassionate perspectives builds emotional resilience and psychological flexibility.

Five Examples of Cognitive Restructuring in Action: Cognitive restructuring often involves transforming dysfunctional core beliefs into healthier alternatives. Core beliefs are deeply ingrained assumptions about oneself, others, and the world. These beliefs are often formed early in life and operate automatically. Below are common dysfunctional beliefs and their healthier replacements:

- “I don’t deserve love” → “I deserve love.” This shift challenges feelings of unworthiness and promotes self-acceptance.

- “I am a bad person” → “I am a good person who sometimes makes mistakes.” Instead of defining identity by isolated actions, this reframing allows for growth and self-forgiveness.

- “I am worthless” → “I am worthwhile.” This change directly confronts global negative self-evaluations.

- “It’s not OK to show emotions” → “It’s OK to feel and express my emotions appropriately.” This reframing supports emotional authenticity and healthier relationships.

- “I can’t trust anyone” → “I can trust some people.” Rather than adopting an extreme, all-or-nothing belief, this new thought introduces nuance and discernment.

Each of these examples illustrates how cognitive restructuring does not create unrealistic positivity; instead, it replaces rigid, absolute, and self-defeating beliefs with balanced and functional alternatives.

Common Cognitive Distortions: Cognitive distortions are systematic errors in thinking that bias how we perceive ourselves and our environment. Beck (1976), a pioneer of CBT, described these distortions as inaccurate and irrational thought patterns that can significantly impact emotional well-being. Although these distortions often occur automatically, they are not facts, they are interpretations shaped by past experiences and underlying schemas.

- Overgeneralization: Overgeneralization occurs when a person draws sweeping conclusions based on a single negative event. For instance, after one failed job interview, someone might think, “I’ll never get hired anywhere.” According to Beck (1976), this distortion transforms isolated incidents into global patterns of failure. Over time, such thinking can erode confidence and discourage future effort.

- Magnification and Minimization: Magnification involves exaggerating the importance of negative events, while minimization downplays positive achievements. Yurica and DiTomasso (2005) describe this distortion as one that distorts evaluation processes. For example, a person might magnify a minor mistake—“I ruined everything”—while minimizing success—“That achievement wasn’t a big deal.” This imbalance reinforces low self-esteem and persistent dissatisfaction.

Why Addressing Cognitive Distortions Matters: Cognitive distortions can damage self-concept, impair decision-making, and fuel emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression (Beck, 1976). When individuals repeatedly interpret experiences through distorted lenses, those interpretations begin to feel like objective truths. Cognitive restructuring interrupts this cycle by introducing deliberate reflection and evidence-based evaluation.

Through consistent practice, individuals learn to pause, question automatic thoughts, examine supporting and contradicting evidence, and generate alternative interpretations. This process gradually weakens dysfunctional schemas and strengthens healthier cognitive habits.

So, cognitive restructuring empowers individuals to become active participants in shaping their internal dialogue. By challenging biased thinking and cultivating balanced perspectives, people can reduce psychological distress, enhance emotional resilience, and develop a more compassionate relationship with themselves.

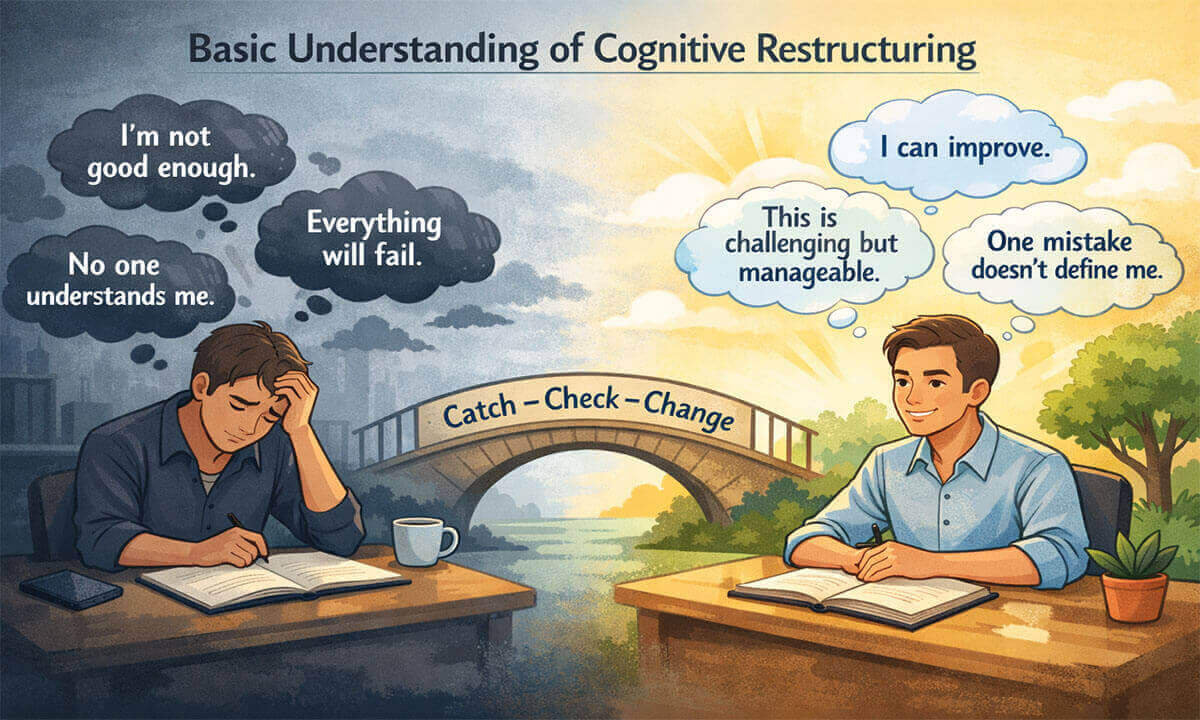

The Three Cs of Cognitive Restructuring:

The “Three Cs” of cognitive restructuring (Catch it, Check it, Change it) provide a simple yet powerful framework for understanding how to work with unhelpful thoughts. Often used in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), this model breaks down the restructuring process into three memorable and practical steps. Although cognitive change can feel complex, the Three Cs translate it into a skill that anyone can learn and practice.

1. Catch It (Becoming Aware of the Thought): The first step is learning to catch the thought. Many of our negative thoughts happen automatically and so quickly that we barely notice them. They often appear as immediate interpretations of situations rather than deliberate reflections.

For example, imagine receiving brief feedback from a supervisor. Within seconds, a thought may arise:

- “I must have done something wrong.”

The emotional reaction (perhaps anxiety or self-doubt) follows almost instantly. If we do not pause to “catch” the thought, we may assume the feeling is caused directly by the event. However, in CBT, we understand that it is the interpretation of the event that shapes the emotional response.

Catching the thought requires:

- Slowing down your reaction

- Noticing emotional shifts

- Asking yourself, “What just went through my mind?”

This step builds self-awareness. Without awareness, change is impossible. With awareness, distorted thinking becomes visible and therefore workable.

2. Check It (Evaluating the Thought): Once the thought is identified, the next step is to check it. This means evaluating whether the thought is accurate, helpful, and supported by evidence.

Here, you move from emotional reasoning (“It feels true, so it must be true”) to analytical reasoning. You ask:

- What evidence supports this thought?

- What evidence contradicts it?

- Am I engaging in a cognitive distortion (e.g., catastrophizing, mind-reading, overgeneralizing)?

- Is there another possible explanation?

- If a friend had this thought, what would I say to them?

For instance, if the thought is:

- “I always mess things up,”

Checking it might reveal:

- Evidence against it: You have completed many tasks successfully.

- Cognitive distortion present:

- Alternative explanation: This was a single mistake, not a pattern of failure.

The purpose of checking is not to dismiss your emotions, but to ensure your thoughts are fair and realistic. Often, we discover that our harshest thoughts lack solid evidence.

3. Change It (Replacing the Thought): The final step is to change the thought into something more balanced and accurate. This does not mean replacing it with blind optimism or unrealistic positivity. Instead, the goal is to develop a rational and compassionate alternative.

For example:

- Original thought: “I embarrassed myself completely.”

- Changed thought: “I felt uncomfortable, but most people probably didn’t notice. Even if they did, everyone makes mistakes.”

Or:

- Original thought: “I’m a failure.”

- Changed thought: “I didn’t succeed this time, but I can learn and improve.”

This new thought typically leads to a shift in emotion; from shame or panic to mild disappointment or determination. Over time, consistently changing distorted thoughts rewires habitual patterns of thinking, increasing emotional resilience and self-confidence.

Why the Three Cs Matter: The strength of the Three Cs lies in their simplicity. They provide a repeatable mental habit that can be used in everyday situations; at work, in relationships, or during moments of stress.

- Catch it builds awareness.

- Check it builds critical thinking.

- Change it builds emotional resilience.

With practice, this process becomes more automatic. Instead of being swept away by negative assumptions, individuals learn to pause, reflect, and respond thoughtfully. The result is not the elimination of difficult emotions, but a healthier and more balanced relationship with one’s thoughts.

Thus, the Three Cs transform cognitive restructuring from a therapeutic concept into a practical life skill; one that empowers individuals to shape their internal dialogue rather than be controlled by it.

How Does Cognitive Reframing Work?

Cognitive reframing operates on one of the central principles of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): our thoughts influence our emotions, and our emotions influence our behaviors. In other words, it is not simply events themselves that determine how we feel, but how we interpret those events. When interpretations are negative, rigid, or distorted, they often give rise to distressing emotions and unhelpful behavioral patterns.

CBT is built on the understanding that maladaptive thinking contributes significantly to psychological distress. For example, if someone thinks, “I failed this presentation; I’m completely incompetent,” they may feel shame or anxiety and avoid future opportunities. However, if the thought becomes, “That presentation didn’t go as well as I hoped, but I can improve,” the emotional response is more likely to be constructive rather than debilitating. The situation remains the same; the interpretation changes and so does the emotional outcome.

Cognitive restructuring requires individuals to actively challenge their automatic negative thoughts rather than accepting them as unquestionable truths. Many of these thoughts arise quickly and feel convincing, which makes them difficult to detect. Over time, they can solidify into deeply held beliefs. The reframing process slows this automatic reaction down. Clients are guided to ask questions such as:

- What evidence supports this thought?

- What evidence contradicts it?

- Am I engaging in a cognitive distortion?

- Is there an alternative explanation?

By systematically examining their thinking, clients begin to recognize that thoughts are mental events, not objective facts.

According to Mills et al. (2008), when applied correctly, cognitive restructuring helps individuals stop automatically trusting their thoughts as accurate representations of reality and instead begin testing them for accuracy. This shift is crucial. Rather than being controlled by unexamined internal narratives, clients learn to evaluate them with curiosity and skepticism.

In practice, cognitive reframing forms the backbone of many CBT sessions. Therapists use a wide range of structured techniques—such as thought records, behavioral experiments, and evidence-for-and-against exercises—to help clients identify distortions and generate more balanced alternatives. These techniques are adaptable and can be applied to various concerns, including anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, stress, and interpersonal conflicts.

Over time, repeated practice strengthens new cognitive habits. Clients begin to internalize a more balanced inner dialogue. They become less reactive to fleeting negative thoughts and more capable of responding thoughtfully rather than impulsively. As Mills et al. (2008) note, this capacity to evaluate and revise one’s thinking is a powerful tool for reducing distress and promoting long-term psychological wellbeing.

Ultimately, cognitive reframing works because it empowers individuals to reshape their internal narratives. By challenging distorted thinking patterns and replacing them with realistic, compassionate alternatives, clients cultivate emotional resilience and healthier behavioral responses, creating meaningful and lasting change.

Six Cognitive Restructuring Techniques:

Although cognitive distortions can feel automatic and deeply ingrained, research and clinical experience show that they are not fixed. With intentional practice and structured intervention, individuals can learn to identify, challenge, and replace distorted thinking patterns with more accurate and adaptive alternatives. Cognitive restructuring techniques have demonstrated considerable effectiveness in helping clients reexamine harmful beliefs and develop healthier cognitive habits. Below are six widely used techniques.

1. Socratic Questioning: Socratic questioning is one of the most powerful and widely used cognitive restructuring tools. Rooted in guided discovery rather than direct confrontation, this technique helps clients evaluate the validity of their thoughts through systematic inquiry.

Rather than telling clients their thoughts are irrational, therapists ask structured questions such as:

- Is this thought realistic?

- Am I basing my thoughts on facts or feelings?

- What evidence supports this belief?

- What evidence contradicts it?

- Could I be misinterpreting the situation?

- Am I seeing this in black-and-white terms when it may be more nuanced?

- Is this thought habitual, or is it supported by objective facts?

This questioning process encourages cognitive flexibility. Clients begin to notice logical gaps, emotional reasoning, and cognitive distortions embedded in their thinking. Over time, they internalize this questioning style and apply it independently, transforming it into a lifelong skill for emotional regulation.

2. Thought Records: Thought records are structured worksheets that help clients track and evaluate their automatic thoughts. According to Myles and Shafran (2015), thought records are especially useful because awareness is the first step in cognitive change. Many distorted thoughts operate below conscious awareness; writing them down brings them into focus.

Although formats may vary, most thought records include:

- The triggering situation

- The automatic thought

- The emotion(s) experienced

- Evidence supporting the thought

- Evidence against the thought

- A more balanced alternative thought

By consistently recording thoughts in real-life situations, clients begin to detect recurring themes and distortions. For example, someone may discover a pattern of catastrophizing or overgeneralizing across different contexts. This structured reflection weakens the automatic power of distorted beliefs and replaces them with reasoned alternatives.

4. Decatastrophizing (“What If” Technique): Decatastrophizing, also called the “what if” technique, is particularly effective for anxiety-driven thinking. It involves asking, “What’s the worst that could realistically happen?” and logically following the feared scenario through to its conclusion (Dattilio & Freeman, 1992).

Instead of stopping at an exaggerated fear—“If I make a mistake, everything will fall apart”—the therapist guides the client step-by-step:

- What would happen next?

- How would you cope?

- Has something similar happened before?

- What resources would you have?

This technique often reveals that the feared outcome is either unlikely or manageable. By systematically examining the catastrophic prediction, clients reduce exaggerated anxiety and regain a sense of control. Even when worst-case scenarios are unpleasant, they are rarely as devastating as imagined.

5. Guided Imagery: Guided imagery uses visualization to access emotionally charged beliefs and assumptions. It is particularly effective when thoughts are tied to vivid internal images rather than purely verbal narratives. Edwards (1989) outlines three primary categories of imagery work within cognitive restructuring.

- Life Event Visualization: The client focuses on a specific meaningful event; either recent (e.g., an argument) or distant (e.g., childhood rejection). The therapist guides the client to revisit the scene mentally, exploring thoughts, emotions, and assumptions associated with it (Edwards, 1989). This process often uncovers core beliefs formed during emotionally significant experiences.

- Reinstatement of a Dream or Daytime Image: Here, the client revisits a previously experienced image; perhaps from a dream, fantasy, or earlier imagery session. Such images often hold symbolic meaning and evoke strong emotions. By reexamining them in a therapeutic setting, clients gain insight into underlying fears or desires.

- Feeling Focusing: In feeling focusing, the client begins with an emotion experienced in the present session. Rather than starting with a memory, the therapist invites the client to sit with the feeling and allow an image to emerge naturally. If the image lacks clarity, multisensory evocation (exploring sights, sounds, textures, or sensations) can deepen the visualization (Edwards, 1989). Once the image is fully formed, the therapist explores its meaning collaboratively.

- Imagery Assessment Techniques: After generating imagery, therapists use specific assessment techniques to uncover its symbolic meaning.

- Prompted Soliloquy: The client becomes an object or entity within the image and speaks from its perspective. For instance, if the image involves a drying lake, the client might speak as the lake, describing its experience.

- Interview: The therapist questions the client while they remain in the role of the object or figure.

- Prompted Dialogue: The client speaks to another element within the image.

- Prompted Descriptions: The therapist frequently asks the client what they see and feel to clarify meaning.

- Prompted Transformation: The therapist suggests altering the image once its meaning is understood.

These techniques help externalize internal conflicts and reveal hidden assumptions in a symbolic yet accessible way.

6. Restructuring Techniques: Once the meaning of an image or thought pattern has been clarified, the therapist guides the client toward restructuring harmful beliefs. Edwards (1989) describes several structured methods.

- Summary and Reframing: The therapist summarizes key insights and gently proposes alternative interpretations based on the imagery and discussion. This step integrates emotional and cognitive insight.

- Directed Dialogue: The client takes on a role from the imagery and speaks specific lines suggested by the therapist, reinforcing new beliefs or challenging old ones.

- Prompted Dialogue: Rather than scripting the response, the therapist encourages the client to generate their own words to express a healthier perspective.

- Directed Transformation: The therapist instructs the client to alter the image; perhaps strengthening a vulnerable figure or removing a threatening one.

- Prompted Transformation: Instead of prescribing the change, the therapist invites the client to imagine a transformation that feels empowering or healing.

Through these restructuring strategies, clients actively revise the symbolic representation of their internal world. This experiential shift often leads to deeper and more lasting cognitive change than purely verbal analysis.

In essence, cognitive restructuring techniques (from Socratic questioning and thought records to guided imagery and transformational dialogue) provide structured pathways for identifying and correcting distorted thinking. Whether through logical examination (Myles & Shafran, 2015; Dattilio & Freeman, 1992) or imagery-based exploration (Edwards, 1989), these tools empower clients to reshape entrenched beliefs. Although cognitive distortions can be persistent, they are not permanent. With practice, clients learn to question automatic assumptions, reinterpret experiences more realistically, and develop cognitive habits that support resilience and psychological wellbeing.

The 5 Steps of Cognitive Restructuring:

Cognitive restructuring is most effective when it follows a clear, structured sequence. Rather than simply telling clients to “think positively,” this method teaches them how to systematically examine and modify distressing thoughts. The American Psychological Association (APA) outlines a practical five steps approach commonly used in CBT-based interventions. Below is a brief explanation of each step.

1. Identify the Situation: The first step is to clearly describe the triggering event. This involves identifying the specific situation that led to emotional distress. It is important to focus on observable facts rather than interpretations.

For example:

- “My supervisor gave me feedback on my report.”

- “I didn’t receive a reply to my message.”

- “I made a mistake during a presentation.”

This step helps separate the objective event from the meaning the individual attaches to it. Without this distinction, people often confuse their interpretations with reality. Clarifying the situation creates a foundation for accurate cognitive analysis.

2. Identify the Emotion: Next, the individual identifies the strongest emotion experienced in response to the situation. Naming the emotion increases emotional awareness and helps regulate intensity.

Common emotions include:

- Sadness

- Anxiety

- Anger

- Shame

- Guilt

- Fear

Clients are often encouraged to rate the intensity of the emotion (e.g., 0–100%). This allows them to observe changes later in the process. By isolating the emotional response, individuals begin to see the connection between thoughts and feelings—an essential principle of CBT.

3. Identify the Automatic Thought: Automatic thoughts are immediate interpretations that arise in response to a situation. They often feel convincing and unquestionable. In this step, the individual articulates the specific belief associated with the emotional reaction.

Examples include:

- “I’m incompetent.”

- “They don’t like me.”

- “I always mess things up.”

- “This is going to end badly.”

These thoughts are often distorted, exaggerated, or rooted in long-standing core beliefs. Writing them down makes them visible and concrete, rather than vague and overwhelming. This clarity is essential for meaningful cognitive change.

4. Analyze and Challenge the Thought: This step is the core of cognitive restructuring. The individual evaluates the automatic thought using evidence-based questioning; often through Socratic dialogue.

Key questions include:

- What evidence supports this thought?

- What evidence contradicts it?

- Am I confusing feelings with facts?

- Am I engaging in a cognitive distortion (e.g., catastrophizing, overgeneralizing)?

- Is there an alternative explanation?

The goal is not to deny emotions but to test the accuracy of the belief. Many automatic thoughts collapse under careful examination. Others may contain partial truths but are exaggerated or incomplete.

By evaluating evidence objectively, individuals begin to shift from emotional reasoning (“I feel it, so it must be true”) to rational analysis.

5. Develop a Rational Rebuttal: The final step involves creating a more balanced, realistic thought to replace the original distorted one. This is not about forced positivity but about accuracy and fairness.

For example:

- Original thought: “I’m terrible at my job.”

- Rational rebuttal: “I made a mistake, but I’ve done many things well. I can learn from this.”

- Original thought: “They didn’t reply because they don’t like me.”

- Rational rebuttal: “There could be many reasons for the delay. I don’t have enough evidence to assume rejection.”

After generating the new thought, the individual reassesses the emotional intensity. In many cases, distress decreases significantly once the belief becomes more balanced. Repeated practice strengthens this cognitive flexibility and reduces the power of distorted thinking patterns over time.

Ultimately, the five steps cognitive restructuring process (identifying the situation, emotion, automatic thought, challenging the belief, and developing a rational rebuttal) provides a structured pathway for transforming distressing thinking patterns. By systematically examining thoughts rather than accepting them as facts, individuals learn to respond to challenges with greater clarity and emotional resilience. As outlined by the American Psychological Association, this structured approach empowers clients to reshape maladaptive beliefs and cultivate healthier cognitive habits.

How Cognitive Restructuring Helps in Treating Mental Health Disorders:

Cognitive restructuring is one of the most powerful and widely used tools in CBT. At its core, it is based on a simple but transformative idea: our thoughts influence our emotions and behaviors. When thinking patterns become distorted, rigid, or overly negative, they can maintain or intensify psychological distress. By identifying and modifying these patterns, cognitive restructuring directly addresses one of the root mechanisms underlying many mental health disorders. Below is a brief look at how this process contributes to treatment and recovery.

1. It Reduces the Power of Automatic Negative Thoughts: Many mental health disorders are fueled by automatic negative thoughts; quick, habitual interpretations that feel true but are often inaccurate. These thoughts shape emotional reactions before a person even realizes what has happened.

For example:

- Depression: “I’m worthless.”

- Anxiety: “Something terrible is going to happen.”

- Social anxiety: “Everyone is judging me.”

- PTSD: “I’m not safe anywhere.”

Cognitive restructuring helps individuals slow down these automatic reactions and examine them critically. By questioning evidence and considering alternative explanations, clients begin to weaken the emotional intensity attached to distorted thoughts. Over time, these thoughts lose their automatic authority.

2. It Interrupts the Thought–Emotion–Behavior Cycle: Mental health disorders often operate in a self-reinforcing loop:

- Distorted thought

- Negative emotion

- Avoidant or maladaptive behavior

- Reinforcement of the distorted thought

For example, in social anxiety:

- Thought: “I’ll embarrass myself.”

- Emotion: Fear

- Behavior: Avoid social events

- Outcome: No disconfirming evidence; anxiety remains

Cognitive restructuring breaks this cycle at the thought level. By challenging the original belief (“What evidence suggests I’ll embarrass myself?”), the emotional intensity decreases, making healthier behaviors possible. When individuals act differently, they gather new evidence that further reshapes their thinking.

3. It Treats Depression by Challenging Negative Core Beliefs: Depression is often characterized by what psychologists call the “negative cognitive triad”—negative views about the self, the world, and the future. Examples include:

- “I am unlovable.”

- “Nothing ever works out.”

- “Things will never get better.”

Cognitive restructuring helps individuals identify these deeply rooted core beliefs and examine their accuracy. Instead of accepting them as facts, clients learn to test them against real-life evidence. Gradually, they replace global, absolute statements with balanced perspectives.

This process reduces hopelessness and self-criticism, two central features of depressive disorders. As thinking becomes more realistic and compassionate, mood typically improves.

4. It Reduces Anxiety by Correcting Catastrophic Thinking: Anxiety disorders often involve overestimating danger and underestimating coping ability. People may engage in catastrophizing (“This will be a disaster”) or mind-reading (“They think I’m incompetent”).

Cognitive restructuring addresses these distortions by:

- Evaluating the likelihood of feared outcomes

- Considering alternative explanations

- Identifying coping resources

- Practicing decatastrophizing (“If the worst happens, how would I handle it?”)

By recalibrating threat perception, anxiety levels decrease. Clients begin to feel more capable and less overwhelmed.

5. It Supports Trauma Recovery by Reframing Meaning: In trauma-related disorders such as PTSD, individuals often develop rigid, self-blaming, or fear-based beliefs:

- “It was my fault.”

- “I should have prevented it.”

- “The world is completely unsafe.”

Cognitive restructuring helps clients differentiate between responsibility and circumstance, examine distorted guilt, and build a more nuanced understanding of the traumatic event. While it does not erase painful memories, it changes the meaning attached to them. This shift reduces shame, fear, and hypervigilance.

6. It Improves Emotional Regulation: When distorted thoughts intensify emotions, those emotions can feel overwhelming. Cognitive restructuring promotes emotional regulation by teaching individuals to pause, reflect, and respond deliberately rather than react impulsively.

Instead of:

- “I feel angry, so this situation is unfair.”

Clients learn:

- “I feel angry. What thought is driving this emotion?”

This separation between feeling and interpretation creates space for calmer decision-making and healthier interpersonal interactions.

7. It Builds Long-Term Resilience: One of the most important benefits of cognitive restructuring is that it teaches a skill—not just symptom management. Clients learn how to:

- Monitor their thoughts

- Identify distortions

- Generate balanced alternatives

- Test beliefs through experience

These skills remain useful long after therapy ends. Individuals become less vulnerable to relapse because they can independently challenge emerging negative patterns.

In this way, cognitive restructuring does not simply reduce symptoms; it strengthens psychological flexibility and resilience.

8. It Enhances Self-Compassion and Self-Efficacy: Many disorders involve harsh self-judgment. Cognitive restructuring encourages fairness and evidence-based self-evaluation. Over time, individuals shift from self-criticism to constructive self-reflection.

For example:

- From: “I’m a failure.”

- To: “I struggled in this area, but I can learn and improve.”

This change fosters self-efficacy (the belief in one’s ability to cope and grow) which is essential for recovery across various mental health conditions.

9. It Promotes Behavioral Change: Thoughts influence actions. When distorted thoughts change, behavior naturally follows. Reduced avoidance, improved communication, healthier risk-taking, and increased engagement in meaningful activities often result from cognitive restructuring.

Behavioral changes then provide real-world evidence that reinforces healthier thinking patterns, creating a positive feedback loop.

Subsequently, cognitive restructuring helps treat mental health disorders by addressing the cognitive distortions that sustain emotional suffering. By teaching individuals to identify, evaluate, and modify unhelpful thoughts, it reduces symptoms of depression, anxiety, trauma-related disorders, and more. Beyond symptom relief, it fosters emotional regulation, resilience, and long-term psychological growth. Cognitive restructuring empowers individuals to move from being passive recipients of their thoughts to active evaluators of them. In doing so, it transforms internal dialogue from a source of distress into a tool for healing and well-being.

It is apparent that cognitive restructuring offers more than just a set of therapeutic techniques; it provides a practical framework for transforming the way we interpret our experiences. While it is natural to develop negative or distorted beliefs over time, these patterns are not fixed or permanent. Through intentional reflection, evidence-based questioning, and consistent practice, individuals can reshape unhelpful thoughts into balanced and constructive perspectives. The distress that stems from faulty thinking is not something we are destined to endure. With the right tools, awareness, and guidance, people can reduce emotional suffering, strengthen resilience, and build healthier relationships with themselves and others. Cognitive restructuring reminds us that while we cannot always control what happens to us, we can learn to influence how we understand and respond to it, and that shift can make all the difference.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Is cognitive restructuring the same as positive thinking?

No, cognitive restructuring is not about forcing positive thoughts or ignoring problems. Instead, it focuses on developing balanced and realistic thinking. The goal is accuracy, not blind optimism. It encourages replacing distorted or exaggerated thoughts with fair and evidence-based alternatives.

What are cognitive distortions?

Cognitive distortions are biased or irrational ways of thinking that can negatively affect how we perceive ourselves and the world. Common examples include:

- All-or-nothing thinking (“If I’m not perfect, I’m a failure.”)

- Catastrophizing (“This is going to be a disaster.”)

- Overgeneralization (“I failed once; I’ll always fail.”)

- Mind-reading (“They must think I’m incompetent.”)

Cognitive restructuring helps identify and correct these distortions.

How does cognitive restructuring improve mental health?

It reduces emotional distress by addressing the thought patterns that fuel conditions like anxiety, depression, and stress. When individuals learn to question automatic negative thoughts and replace them with balanced ones, emotional intensity decreases, and healthier behaviors become possible.

Can I practice cognitive restructuring on my own?

Yes, many aspects can be practiced independently using tools such as thought records, journaling, and the “Catch it, Check it, Change it” method. However, working with a trained therapist can provide deeper insight, structure, and support; especially for complex or long-standing issues.

How long does it take to see results?

The timeline varies depending on the individual and the severity of the issue. Some people notice shifts in emotional intensity after just a few sessions, while long-term change may take consistent practice over weeks or months. Like any skill, cognitive restructuring becomes more effective with repetition.

Does cognitive restructuring eliminate negative thoughts completely?

No, negative thoughts are a normal part of human experience. The goal is not elimination but management and evaluation. Cognitive restructuring teaches individuals not to automatically believe every negative thought that arises.

Who can benefit from cognitive restructuring?

Anyone experiencing stress, self-doubt, anxiety, depression, or difficulty managing emotions can benefit. It is also useful for personal growth, improving decision-making, and building resilience—even for individuals without a diagnosed mental health disorder.

What is the first step in cognitive restructuring?

The first step is becoming aware of your automatic thoughts. This involves noticing emotional shifts and asking yourself, “What was I just thinking?” Awareness is the foundation for meaningful change.

Why is cognitive restructuring considered effective?

Because it targets one of the central drivers of emotional distress—distorted thinking. By systematically identifying, evaluating, and replacing inaccurate beliefs, it creates lasting cognitive and emotional shifts rather than temporary symptom relief.

References:

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Handout 27: 5 steps of cognitive restructuring instructions. APA. Retrieved February 20, 2026, from https://www.apa.org/pubs/books/supplemental/Treatment-for-Postdisaster-Distress/Handout-27.pdf

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and emotional disorders. International Universities Press.

- Clark, D. A. (2013). Cognitive restructuring. In S. G. Hoffman, D. J. A. Dozois, W. Rief & J. Smits (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of cognitive behavioral therapy (pp. 1–22). John Wiley & Sons.

- Dattilio, F. M., & Freeman, A. (1992). Introduction to cognitive therapy. In A. Freeman & F. M. Dattilio (Eds.), Comprehensive casebook of cognitive therapy (pp. 3–11). Springer.

- Edwards, D. (1989). Cognitive restructuring through guided imagery: Lessons from Gestalt therapy. In A. Freeman, K. M. Simon, L. E. Beutler & H. Akrowitz (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of cognitive therapy (pp. 283–297). Springer.

- Mills, H., Reiss, N., & Dombeck, M. (2008). Cognitive restructuring. Mental health. Retrieved February 20, 2026, from https://www.mentalhelp.net/articles/cognitive-restructuring-info/

- Myles, P., & Shafran, R. (2015). The CBT handbook: A comprehensive guide to using cognitive behavioural therapy to overcome depression, anxiety and anger. Robinson.

- Santos, B., Pinho, L., Nogueira, M. J., Pires, R., Sequeira, C., & Montesó-Curto, P. (2024). Cognitive restructuring during depressive symptoms: A scoping review. Healthcare, 12(13), 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131292

- Stevenson, J., Mattiske, J. K., & Dixon, R. D. V. (2019). The effect of a brief online self-compassion versus cognitive restructuring intervention on trait social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 123, Article 103492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103492

- Yurica, C. L., & DiTomasso, R. A. (2005). Cognitive distortions. In S. Felgoise, A. M. Nezu, C. M. Nezu & M. A. Reinecke (Eds.), Encyclopedia of cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 117–122). Springer.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College