Basic Concept of Self-Esteem:

Self-esteem is one of the most fundamental yet often misunderstood aspects of human psychology. From childhood fairy tales to modern motivational slogans, the idea of “Believing in Yourself” is celebrated as a magical key to unlocking potential and achieving dreams. While this notion is sometimes exaggerated, the truth remains that healthy self-esteem does have a powerful impact on how we live, work, and relate to others. It shapes our confidence, influences our choices, and affects our resilience in the face of challenges. Understanding what self-esteem truly is—and how it supports our well-being—can help us nurture it in ourselves and encourage it in those around us, especially in children who are still forming their sense of self-worth. In the rest of this article, we will explore the basic concept of self-esteem.

What is the Meaning of Self-Esteem?

You probably already have an idea of what self-esteem is, but it is worth revisiting its meaning in detail to truly appreciate its impact on our lives. At its core, self-esteem refers to a person’s overall sense of value and self-worth. Put simply, it is how much we appreciate and accept ourselves. Adler and Stewart (2004) describe self-esteem as the degree to which a person “values, approves of, appreciates, prizes, or likes him or herself.”

One of the leading voices in the field of self-esteem research, Morris Rosenberg, offered a straightforward definition back in 1965: he described self-esteem as an individual’s general “favourable or unfavourable attitude toward the self.” This attitude can range from high self-regard and confidence to feelings of inadequacy or self-doubt.

Self-esteem is shaped by a variety of factors that interact throughout our lives. These include genetics, which influence temperament; personality traits, such as optimism or resilience; and life experiences, such as successes and failures that leave a mark on how we see ourselves. Other elements like age, health, and the thoughts we entertain daily also contribute to how we evaluate our worth. Social factors are equally important: our social circumstances, the reactions of others, and how often we compare ourselves to others can either strengthen or weaken our sense of self-esteem over time.

A key point to remember is that self-esteem is not something static or permanent—it is both malleable and measurable. This means we can assess our current level of self-esteem and take steps to improve it if needed.

Self-Esteem vs. Self-Acceptance:

While people often use self-esteem and self-acceptance interchangeably, they are not the same. Understanding the differences between these two concepts is crucial, as they lead to different ways of relating to ourselves and affect our wellbeing in distinct ways.

Self-esteem depends on evaluation. It involves judging ourselves and rating our traits or actions as either good or bad. This judgment shapes whether we see ourselves as worthy or unworthy (Ellis, 1994). In contrast, self-acceptance does not involve judgment but instead focuses on embracing oneself as a whole. It means relating to the self in a way that allows it to be, without labels of good or bad (Ellis, 1976).

Another important difference is that self-esteem is heavily rooted in comparison—it often hinges on how we measure up to others in terms of performance, appearance, or achievements. Self-acceptance, however, comes from realizing that there is no objective standard for judging the worth of a human being. It is an unconditional affirmation that we are enough as we are, regardless of how we compare to anyone else.

Furthermore, self-esteem is contingent on external factors. Our sense of worth might rise or fall based on our successes, failures, or how others react to us. This makes self-esteem inherently fragile and easily shaken. Self-acceptance, on the other hand, provides a more stable and lasting foundation. Because it is not dependent on external approval or performance, it fosters a secure and enduring positive relationship with the self (Kernis & Lakey, 2010).

When it comes to wellbeing, both self-esteem and self-acceptance have been linked to positive outcomes. High self-esteem is associated with greater life satisfaction (Myers & Diener, 1995) and lower levels of anxiety (Brockner, 1984). However, an excessive focus on self-esteem can backfire, sometimes feeding into egotism and narcissism (Crocker & Park, 2003). Self-acceptance, in contrast, is strongly tied to consistent, deep-rooted psychological wellbeing across multiple aspects of life (MacInnes, 2006).

Ultimately, while cultivating healthy self-esteem is valuable, nurturing self-acceptance may offer a more reliable path to genuine inner peace and resilience.

Self-Esteem and Psychology:

Self-esteem has long been one of the central topics in the field of psychology, stretching back to the very origins of the discipline itself. Even Sigmund Freud—often regarded as the founding father of modern psychology, though his ideas are viewed with a more critical lens today—recognized the significance of self-esteem in his theories about the human mind. Freud’s work suggested that our sense of self-worth plays a vital role in shaping how we think, feel, and behave.

Since then, countless psychologists have sought to understand what self-esteem truly is, how it develops or falters over time, and how it influences our mental health and day-to-day life. Despite decades of research, these questions continue to intrigue researchers, and there’s still no final, all-encompassing answer in sight. What we do know, however, is that self-esteem is distinct from other closely related concepts. Understanding these differences helps us better grasp how self-esteem fits into the bigger picture of human psychology.

- Self-Esteem vs. Self-Concept: First, it’s important to separate self-esteem from self-concept. While the two are connected, they are not the same. Self-concept refers to the way we perceive ourselves—our personal answer to the question, “Who am I?” It is our understanding of our own traits, habits, thoughts, preferences, strengths, weaknesses, and unique characteristics.

Purkey (1988) described self-concept as “the totality of a complex, organized, and dynamic system of learned beliefs, attitudes, and opinions that each person holds to be true about his or her personal existence.” In this sense, self-concept is broad and all-encompassing. According to Carl Rogers, the founder of client-centered therapy, self-esteem is actually a component within the larger framework of self-concept (McLeod, 2008).

- Self-Esteem vs. Self-Image: Another related term is self-image. Like self-concept, self-image concerns how we see ourselves—but with an important twist. Self-image may not always align with reality; it can be shaped by distorted thoughts or false beliefs about who we are (McLeod, 2008). In other words, our self-image might be realistic, overly negative, or unrealistically positive, but it rarely matches objective reality or how others truly see us.

- Self-Esteem vs. Self-Worth: People also sometimes confuse self-esteem with self-worth, but they are slightly different. Self-esteem is about what we think, feel, and believe about ourselves in terms of value and capability. Self-worth, however, is broader: it is the fundamental belief that we are valuable human beings who deserve love and respect simply because we exist (Hibbert, 2013). This difference highlights that while self-esteem can fluctuate, self-worth ideally remains constant and unconditional.

- Self-Esteem vs. Self-Confidence: Self-esteem is not the same as self-confidence either. Self-confidence is the trust we have in our abilities to handle tasks, face challenges, solve problems, and interact effectively with the world around us (Burton, 2015). Self-confidence often relies on our track record of external success—things we have done or can do well. It is possible for someone to have high self-confidence in certain areas (like sports or public speaking) but still struggle with low overall self-esteem if they don’t feel a general sense of self-worth.

- Self-Esteem vs. Self-Efficacy: Closely related to self-confidence is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is the belief in our ability to achieve specific goals or perform particular tasks (Neil, 2005). For example, a student might feel a high sense of self-efficacy in their ability to play the piano but feel low self-efficacy when it comes to passing a math exam. Unlike self-esteem—which reflects a general sense of worth—self-efficacy is task-specific and based on performance and experience.

- Self-Esteem vs. Self-Compassion: One more concept worth distinguishing is self-compassion. Self-compassion focuses on how we treat ourselves when we face difficulties or failures (Neff, n.d.). It is not about judging ourselves as good or bad but about offering kindness, understanding, and forgiveness to ourselves, especially during tough times. Practicing self-compassion can strengthen self-esteem, but the two are not the same thing. Where self-esteem is about evaluating worth, self-compassion is about embracing our humanness with warmth and patience.

- Esteem in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Many people also connect self-esteem with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, a theory that places esteem needs at the fourth level of his pyramid (According to Maslow’s popular Hierarchy of Needs model, all human beings have needs relating to five key domains: Physiological, Safety, Love/belonging, Esteem, Self-actualization). Maslow suggested that human motivation is built around fulfilling various needs, starting with basic physical needs and moving up toward self-actualization.

In Maslow’s hierarchy, esteem needs include external factors such as respect, status, recognition, and prestige, along with internal self-respect (McLeod, 2017). While self-esteem is part of this level, Maslow emphasized that the respect and esteem we receive from others can be just as critical to our growth as our inner sense of worth. He believed that only when our esteem needs—both from ourselves and from our social world—are met can we progress to self-actualization and reach our fullest potential.

In brief, although self-esteem overlaps with other self-related ideas like self-concept, self-worth, self-confidence, self-efficacy, and self-compassion, each of these plays a unique role in how we view ourselves and navigate the world. Understanding these differences helps us appreciate the depth of self-esteem’s influence and why it continues to be a fascinating topic in psychology.

Incorporating Self-Esteem in Positive Psychology:

The topic of self-esteem continues to stir debate within the field of psychology—especially in the realm of positive psychology, which focuses on what helps individuals and communities thrive. Dr. Martin Seligman, one of the founding figures of positive psychology, has voiced thoughtful reservations about embracing self-esteem uncritically within this field. In 2006, Seligman argued that modern society risks placing too much emphasis on building self-esteem at all costs, sometimes without concern for whether it is rooted in real achievement or healthy self-awareness. He explained:

“I am not against self-esteem, but I believe that self-esteem is just a meter that reads out the state of the system. It is not an end in itself. When you are doing well in school or work, when you are doing well with the people you love, when you are doing well in play, the meter will register high. When you are doing badly, it will register low.” (Seligman, 2006, p. v)

Seligman’s caution reminds us that self-esteem, while valuable, should not be treated as an isolated goal to chase blindly. Instead, it is best understood as a reflection of healthy functioning in other parts of life—such as meaningful work, rewarding relationships, and authentic self-expression. This perspective encourages researchers, coaches, and practitioners to look critically at how self-esteem fits into the bigger picture of well-being.

What High Self-Esteem Looks Like:

Despite concerns about artificially inflating self-esteem, research and observation have helped clarify what genuine, healthy self-esteem looks like in daily life. According to Branden (1992), people with high self-esteem show certain clear traits: they are open to constructive criticism, willing to admit mistakes, and comfortable both giving and receiving compliments. They tend to act in a way that shows harmony between what they say, do, and believe, and how they present themselves to the world.

People with high self-esteem often demonstrate curiosity about life and are eager to share their thoughts, ideas, and experiences with others. They can find humor in life’s ups and downs and feel comfortable asserting themselves in personal and social situations. The positive psychology movement has helped shine more light on these strengths, shifting some of the focus away from just treating low self-esteem to exploring how to foster strong, authentic self-worth.

Research and practical examples show that people with high self-esteem often:

- Appreciate themselves and others for who they are.

- Seek personal growth, meaning, and fulfillment in life.

- Express creativity and explore their inner potential.

- Make independent choices, aligning with their own values rather than simply conforming to others’ expectations.

- See the world realistically, accepting others as they are while encouraging positive change.

- Solve problems effectively and stay focused on solutions rather than dwelling on blame.

- Build healthy, loving relationships based on respect and honesty.

- Live according to clear personal values, speaking openly and kindly about their needs, opinions, and desires.

- Work to make a positive difference in other people’s lives (Smith & Harte, n.d.).

There are also practical signs that suggest a person has healthy self-esteem (Self Esteem Awareness, n.d.). If you:

- Act assertively and communicate freely without guilt.

- Focus on the present rather than getting stuck in past regrets.

- Believe you are equal to others—not better, not worse.

- Resist manipulation by standing firm in your beliefs.

- Accept and share your full range of feelings in safe relationships.

- Balance work, play, and rest.

- Take risks and face challenges to grow, learning from mistakes instead of being defined by them.

- Accept criticism without feeling personally attacked, seeing it as an opportunity to learn.

- Freely express your likes and dislikes and communicate honestly.

- Accept others for who they are instead of trying to change them.

To make this more concrete, imagine a student who receives a failing grade on an exam. A person with low self-esteem might internalize that failure and start believing they are inherently unintelligent or destined to keep failing. In contrast, a student with high self-esteem will likely view the bad grade as a single setback. They might analyze what went wrong—perhaps they didn’t study enough or didn’t understand some key concepts—and then develop a plan to improve. The failure is an event, not a defining label.

Or picture a young man on a first date. He genuinely likes his date but realizes they have very different opinions and values. Instead of pretending to agree to impress her, he confidently shares his own views and stays true to himself. His self-esteem allows him to be authentic rather than seeking approval at the cost of his values.

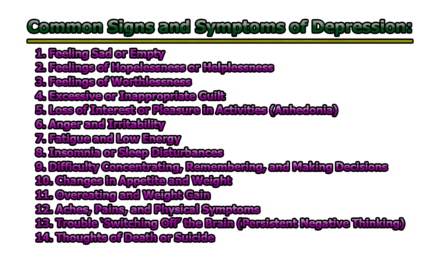

Signs of Low Self-Esteem:

On the other end of the spectrum, low self-esteem can reveal itself in many ways—often undermining a person’s confidence, relationships, and goals. Here are the examples of issues that commonly stem from low self-esteem:

- People-pleasing at the expense of one’s own needs.

- Feeling easily angered or irritated.

- Believing one’s opinions don’t matter.

- Hating oneself.

- Feeling that nothing one does is good enough.

- Being overly sensitive to others’ opinions.

- Feeling unsafe or threatened by the world.

- Doubting every decision, big or small.

- Frequently feeling sad or worthless.

- Struggling to maintain healthy relationships.

- Avoiding risks or new experiences.

- Engaging in addictive behaviors to escape discomfort.

- Lacking confidence in abilities.

- Struggling to set or maintain boundaries.

- Focusing more on weaknesses than strengths.

- Feeling unsure about one’s identity.

- Being consumed by negative past experiences.

- Struggling to say “no” to unreasonable demands.

- Struggling to ask for one’s needs to be met.

- Holding a pessimistic outlook on life.

- Doubting personal abilities or chances of success.

- Experiencing frequent negative emotions like fear, anxiety, or depression.

- Comparing oneself to others and often feeling inferior as a result.

Surprising Statistics and Facts About Self-Esteem:

Self-esteem is a deeply personal concept, yet its impact stretches far beyond the individual—it touches families, communities, and even entire societies. While we often hear that self-esteem is important, it can sometimes be hard to truly grasp just how much it shapes people’s behaviors, choices, and mental well-being. To make this clearer, here are some striking statistics and facts that reveal just how powerful—and sometimes fragile—self-esteem can be, especially for young people and girls. Some of these findings may sound familiar, but others might surprise you with their depth and implications for daily life.

Eye-Opening Facts About Self-Esteem and Its Impacts: For starters, self-esteem can influence the way teenagers navigate major life choices, including sexual behavior. Research has found that adolescent boys with high self-esteem are almost two and a half times more likely to initiate sexual activity than boys with low self-esteem. Interestingly, the pattern is reversed for girls: girls with high self-esteem are about three times more likely to delay sex compared to girls with low self-esteem (Spencer, Zimet, Aalsma, & Orr, 2002).

Low self-esteem has also been strongly linked to serious problems like violence, school dropout, teenage pregnancy, suicide, and lower academic performance (Misetich & Delis-Abrams, 2003). These connections highlight how deeply a lack of self-worth can disrupt young people’s development and future opportunities.

Body image is another area where self-esteem plays a huge role—especially for girls and women. Statistics show that about 44% of high school girls and 15% of boys are actively trying to lose weight, even if it is not medically necessary (Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse, n.d.). Perhaps even more concerning, seven in ten girls believe they are not good enough or don’t measure up in some way (Dove Self-Esteem Fund, 2008).

For many girls, how they feel about their body shape and weight has a stronger impact on self-esteem than what they actually weigh (Dove Self-Esteem Fund, 2008). This means that perception—often shaped by social media and cultural standards—can be more influential than reality.

Unfortunately, these pressures don’t disappear in adulthood. Nearly 90% of women report wanting to change at least one aspect of their physical appearance (Confidence Coalition, n.d.). Among young girls, the fear of gaining weight starts alarmingly early: 81% of 10-year-old girls are afraid of becoming fat (Confidence Coalition, n.d.). These fears can have lasting consequences—about one in four college-age women struggle with an eating disorder (Confidence Coalition, n.d.), and only a tiny fraction of women—just 2%—report that they think they are beautiful (Confidence Coalition, n.d.).

Low self-esteem can also be shaped by external life circumstances. Studies show that absent fathers, poverty, and a low-quality home environment all have significant negative impacts on a child’s developing self-esteem (Orth, 2018).

The Other Side of the Story (What Healthy Self-Esteem Brings): These statistics paint a sobering picture of just how widespread low self-esteem can be, but it’s important to remember that this is only part of the story. Many people do develop a healthy sense of self-esteem, and when they do, the benefits are wide-ranging and powerful.

According to Allegiance Health (2015), people with healthy self-esteem:

- Are less critical of themselves and others, creating more supportive and positive social interactions.

- Cope better with stress and are less likely to experience its harmful physical and mental side effects.

- Have a lower risk of developing eating disorders and body image issues.

- Are less likely to be overwhelmed by feelings of worthlessness, guilt, or shame.

- Communicate assertively and are more comfortable asking for what they want and need.

- Build stronger, more honest relationships and are more willing to leave relationships that are unhealthy or damaging.

- Trust themselves to make sound decisions and take responsibility for their choices.

- Are more resilient, bouncing back more easily from setbacks, disappointments, and failures.

Why This Matters: These facts show that self-esteem is not just a personal feel-good concept—it shapes mental health, life choices, and social outcomes in profound ways. The difference between healthy and low self-esteem can mean the difference between resilience and hopelessness, authentic relationships and toxic ones, growth and stagnation.

Given these realities, investing time and effort into understanding how to build healthy self-esteem is not just worthwhile—it’s necessary. Whether we are parents, teachers, counselors, or simply people who care about the well-being of ourselves and others, learning to nurture genuine self-esteem could be one of the most meaningful contributions we make to creating healthier, happier lives.

Relevant Research on Building Self-Esteem (What We Know and How to Grow It):

Thankfully, self-esteem is not some fixed trait that we’re born with and stuck with forever. For decades, researchers have explored how self-esteem develops, how it can be nurtured—especially in children and teenagers—and what practical steps can help people strengthen it throughout life. These studies show that building self-esteem is not only possible, but that it can lead to healthier, happier lives.

One example comes from a study with Brazilian university students, where researchers found a positive link between self-esteem and optimism—suggesting that those who feel better about themselves are more likely to maintain a hopeful, forward-looking attitude (Bastianello, Pacico, & Hutz, 2014).

A broader, fascinating look at this topic comes from a cross-cultural study on life satisfaction and self-esteem conducted across 31 countries. It revealed an interesting cultural twist: self-esteem tends to be lower in collectivist cultures compared to individualistic ones (Diener & Diener, 1995). Why? In cultures that value community and group harmony over individual expression, people may feel less encouraged to freely express personal thoughts and emotions—two things strongly tied to self-esteem in Western contexts.

Yet, even in collectivist countries like China, self-esteem has been found to be a key factor in life satisfaction. In China, researchers discovered that teenagers with higher self-esteem were not only more satisfied with life but also more resilient. Those with low self-esteem, however, showed more hopelessness and lower resilience in the face of life’s challenges (Chen, Cheung, Bond, & Leung, 2006; Karatas, 2011).

In individualistic cultures, the story is slightly different. Teens who are encouraged to trust their own beliefs and express themselves openly tend to have both higher self-esteem and stronger resilience when facing adversity (Dumont & Provost, 1999).

How Schools Can Help Build Self-Esteem: Schools play an especially important role in shaping self-esteem. Research confirms that well-designed school programs can make a real difference. For example, pairing students with mentors and creating activities that focus on relationship-building, goal setting, and academic support has been shown to improve students’ self-esteem, help them form healthier relationships, and reduce bullying and depression (King, Vidourek, Davis, & McClellan, 2009).

Even simple, short programs built into regular class time can help. Classroom-based lessons focused on self-esteem can boost students’ self-worth, reduce problem behaviors, and strengthen connections between classmates (Park & Park, 2014).

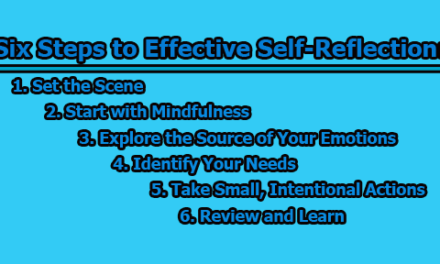

Adults Can Boost Self-Esteem Too: Of course, growing self-esteem is not just for kids—adults can benefit just as much. According to self-esteem researcher Dr. John M. Grohol, there are clear, practical steps that adults can take to strengthen their sense of self-worth (Grohol, 2011):

- Take a self-esteem inventory: Write down 10 strengths and 10 weaknesses to get a clear, honest picture of yourself.

- Set realistic goals: Focus on small, achievable steps you control, rather than setting yourself up for disappointment with impossible demands.

- Stop being a perfectionist: Learn to acknowledge both successes and mistakes, seeing errors as opportunities to grow.

- Explore yourself: Spend time understanding who you really are and what you value—this journey is lifelong.

- Update your self-image: Allow your view of yourself to grow and evolve as you do.

Quit comparing yourself to others. This is easier said than done but vital—compare yourself only to your past self, not to the edited highlight reels you see online.

More Practical Tips for Building Self-Esteem: Beyond Grohol’s advice, other experts have offered everyday habits that can strengthen self-esteem. For example, Henrik Edberg’s Positivity Blog recommends practical ideas like:

- Telling your inner critic to stop.

- Motivating yourself with kindness rather than fear.

- Taking two-minute breaks to appreciate yourself.

- Writing down three things each night that you appreciate about yourself.

- Replacing perfectionism with progress.

- Learning from mistakes instead of dwelling on them.

- Being kind to others (which helps you feel better about yourself too).

- Spending less time comparing yourself to others, especially online.

- Surrounding yourself with supportive, positive people (Edberg, 2017).

The Entrepreneur website adds even more concrete strategies (Laurinavicius, 2017):

- Use distancing pronouns: When feeling stressed, talk about yourself in the third person to get perspective (e.g., “Sarah is feeling anxious”).

- Remind yourself of your achievements: Keep a list to counter feelings of imposter syndrome.

- Get moving: Even a quick walk can lift your mood and self-image.

- Use the five-second rule: Act on good ideas quickly before doubt creeps in.

- Visualize success: Imagine reaching your goals in vivid detail.

- Be prepared: Whether it’s a job interview or a date, preparation builds confidence.

- Limit social media: Too much screen time fuels unfair comparisons.

- Meditate: This helps separate you from your thoughts and reduce harsh self-judgment.

- Keep some goals to yourself: It can boost your commitment and satisfaction when you reach them.

- Use positive affirmations: Simple statements can reshape negative thought patterns over time.

- Embrace failure as a teacher: Growth often happens when we fail and try again.

One important takeaway from all this research and advice is that self-esteem is both a cause and an effect. Yes, boosting your self-esteem can improve your performance at school or work, your relationships, and your mental health. But the reverse is true too—succeeding at work, achieving goals, and building healthy relationships naturally help grow your self-esteem.

So, rather than thinking of self-esteem as an isolated project, it’s more useful to see it as part of a larger effort to grow, connect, and thrive. When we work on the whole picture—developing skills, building connections, and caring for ourselves kindly—healthy self-esteem follows naturally.

Can We Help Boost Self-Esteem Issues with Therapy and Counseling?

When it comes to addressing low self-esteem, therapy and counseling can be among the most powerful and lasting forms of help. Research and decades of practice have shown that when therapy is done with care and the right approach, it can genuinely transform how people see themselves, helping them move from harsh self-criticism to genuine self-acceptance and self-respect.

At the heart of this process is the therapeutic relationship itself. When a client opens up about their deepest thoughts and feelings—and the therapist responds not with judgment, correction, or criticism but with acceptance, curiosity, and compassion—it can lay the groundwork for healthy self-esteem to grow. Feeling truly heard and accepted helps clients begin to think: “Maybe there’s nothing fundamentally wrong with me after all.”

Over time, this safe space and unconditional positive regard encourage clients to challenge their old beliefs about themselves. As Gilbertson (2016) explains, a good therapist will help clients see that self-esteem is not an unchangeable fact—it’s a belief, shaped by past experiences. By recognizing that their low self-esteem is rooted in those past experiences, clients can begin to accept that they could be exactly the same person today and still hold a higher opinion of themselves—if their early experiences had been different.

Therapists can also create new, healthier emotional experiences for clients to build upon. For example, the simple experience of feeling “basically acceptable” in the presence of the therapist—rather than “basically flawed”—gives clients a powerful, new point of reference. In this way, the therapist’s acceptance becomes a living example of how the client might learn to accept themselves too.

Crucially, this does not mean the therapist approves of every action a client takes—but rather, they communicate that at the core, the person themselves is acceptable and worthy of care and respect. Over time, this deep, genuine acceptance can have a transformative effect on a client’s self-belief and confidence (Gilbertson, 2016).

When done well, this process helps clients develop healthier self-love, self-worth, and self-acceptance. It also teaches them how to let go of unnecessary shame and separate their actions (which can change and improve) from their inherent value as human beings (Gilbertson, 2016).

The Benefits of Developing Self-Esteem with Meditation:

Beyond therapy and counseling, self-help practices like meditation have also been shown to support healthy self-esteem. Meditation is often praised for its many mental health benefits—reducing stress, increasing focus, promoting emotional balance—and boosting self-esteem can be added to that list.

At first glance, meditation might not seem like an obvious path to greater self-worth. After all, meditation is about letting go of thoughts rather than trying to directly build yourself up. But that is exactly where its power lies.

As meditation expert Andy Puddicombe (2015) points out, one reason self-esteem suffers is that we often get overly entangled with our thoughts about ourselves. We latch onto negative ideas—I’m not good enough, I failed again, No one likes me—and accept them as facts. When we meditate, however, we practice stepping back from those thoughts, observing them without reacting or attaching too much weight to them.

This process of de-identification—seeing thoughts simply as passing mental events rather than absolute truths—gradually loosens our grip on harsh self-judgment. Instead of getting stuck in repetitive negative self-talk, we learn to let unhelpful thoughts drift by.

Puddicombe (2015) explains that low self-esteem is often the result of over-identifying with our sense of self—believing we are every negative thought that pops into our mind. By practicing meditation, we learn to notice these thoughts without merging with them. We gain freedom from the critical inner voice that used to dominate our mind.

Over time, this mental distance reduces the power of harsh self-judgments and helps us relate to ourselves with more kindness and understanding. Instead of being at the mercy of every negative idea, we become more anchored in the present moment and our basic worth as human beings—flaws and all.

Can You Test Self-Esteem and What Are the Problems with Assessment?

Self-esteem has long been a central concept in psychology, and with that importance comes the need to measure it accurately. Over the decades, many different psychological scales and assessments have been developed to try to quantify this deeply personal, subjective experience. While these tools can be useful and informative—especially for researchers, therapists, and educators—they are not without limitations.

One major challenge is that there is no single, universally agreed-upon definition of what self-esteem actually is (Demo, 1985). Some definitions focus on global self-worth, while others emphasize specific domains like social competence or academic ability. This lack of consensus makes it difficult to create assessments that truly capture the same thing every time.

Another factor to consider is gender differences. Research has shown that there can be significant overall differences in how self-esteem presents across genders (Bingham, 1983). These differences can influence results, so it’s important to interpret scores with cultural and social contexts in mind rather than assuming that a single number tells the whole story.

In addition, there are simply too many instruments out there to measure self-esteem, which can be both a blessing and a curse. While variety can offer choice and specificity, it also leads to inconsistencies: many of these tools do not correlate strongly with each other (Demo, 1985). This means that someone could take two well-known self-esteem scales and get noticeably different results.

One more complication is the gap that often appears between self-reports—what people say about themselves—and “inferred” measures, such as ratings given by friends, teachers, or parents (Demo, 1985). People may underreport or overreport their self-esteem for various reasons, while others’ impressions might miss the nuances of a person’s inner experience.

For these reasons, researchers and practitioners are encouraged to approach self-esteem measurement with care. It’s wise to combine multiple measures, look at results critically, and use self-esteem scores alongside other information rather than relying on them in isolation.

Measuring Self-Esteem with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Despite the limitations, some self-esteem measures have stood the test of time and remain trusted and widely used today. The best-known and most widely used is the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE), developed by Morris Rosenberg and published in his 1965 book Society and the Adolescent Self-Image.

The Rosenberg Scale is straightforward, consisting of just 10 statements about general self-worth and self-acceptance. Respondents rate each item on a four-point scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Items like “I feel that I’m a person of worth” or “I take a positive attitude toward myself” are scored normally, while items that express negative self-assessment, such as “I feel I do not have much to be proud of,” are reverse-scored.

The ten items are:

- On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.

- At times I think I am no good at all.

- I feel that I have a number of good qualities.

- I am able to do things as well as most other people.

- I feel I do not have much to be proud of.

- I certainly feel useless at times.

- I feel that I’m a person of worth.

- I wish I could have more respect for myself.

- All in all, I am inclined to think that I am a failure.

- I take a positive attitude toward myself.

Items 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 are reverse-scored. After scoring, the points are summed to yield a single self-esteem score. Typically, lower total scores indicate higher self-esteem, while higher scores suggest lower self-esteem.

The RSE remains popular because it is simple, reliable, and highly consistent. Its results correlate well with other measures of self-esteem and show negative correlations with scales measuring depression and anxiety. This makes it a practical and trusted choice for both research and practical assessments.

The Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory: Another widely used tool is the Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory, developed by Stanley Coopersmith in the 1960s and refined in the 1980s. This assessment consists of 50 items where respondents indicate whether statements are “like me” or “not like me” (Robinson, Shaver & Wrightsman, 2010).

The Coopersmith Inventory was initially designed for children, aiming to measure their general self-regard and attitudes about themselves in different contexts, including social, academic, and family life. Later, Ryden (1978) adapted it for adults, recognizing that self-esteem remains vital well beyond childhood and adolescence.

Like the Rosenberg Scale, the Coopersmith Inventory has proven to be valid and reliable and remains popular among educators, researchers, and clinicians. It provides a broader look at how people evaluate themselves in various areas of life, rather than focusing solely on global self-worth.

In the end, measuring self-esteem can be incredibly useful—but it should always be done thoughtfully. Tools like the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and the Coopersmith Inventory give us valuable insights, yet it’s essential to remember that no single number can perfectly capture the rich, complex, and evolving nature of how a person feels about themselves. Combining multiple tools, considering the context, and using results as one piece of the bigger picture is the best way to truly understand self-esteem.

Factors That Influence Self-Esteem:

When we think about what shapes our sense of self-worth, the real challenge isn’t identifying which factors matter—it’s realizing just how many things can play a role. Self-esteem is a deeply layered and ever-evolving aspect of who we are. It is shaped by a wide range of personal, social, economic, and psychological factors that interact in complex ways, sometimes boosting our self-respect and confidence, and other times undermining it.

Let’s break down some research-backed influences that illustrate just how broad and interconnected the roots of self-esteem truly are:

One notable influence is the roles we commit to in life. Research has found that people who are committed to their worker, spousal, and parental roles tend to report higher levels of self-esteem (Reitzes & Mutran, 1994). This suggests that feeling dedicated and responsible in these areas can reinforce a sense of purpose and personal value.

Work identity is another piece of the puzzle. The meaning we attach to our role as a worker—how significant and fulfilling we perceive it to be—has been shown to positively relate to self-esteem as well (Reitzes & Mutran, 2006). People who feel that their work matters often feel better about themselves overall.

Interestingly, age and marital status can also play a role, but not always in the ways we might expect. Being married and older has been associated with lower self-esteem in some studies (Reitzes & Mutran, 2006). This could be because aging and long-term relationship dynamics sometimes introduce new stressors, feelings of stagnation, or shifting identities that challenge how people view themselves.

Educational level and income, on the other hand, have been repeatedly linked to higher self-esteem (Reitzes & Mutran, 2006). The greater sense of agency, opportunities, and respect that often come with education and financial security can significantly strengthen one’s confidence and self-worth.

Socioeconomic status is equally powerful in the opposite direction. People living in poverty or with limited resources often struggle with lower self-esteem, partly due to the stress and social stigma attached to economic hardship (von Soest, Wagner, Hansen, & Gerstorf, 2018).

Relationship status can make a difference too. Research has shown that living alone—without a partner or significant other—can be linked to lower self-esteem (von Soest et al., 2018). Human beings are social creatures, and meaningful connections tend to provide us with a sense of belonging and validation that supports a healthier self-image.

Employment and health also matter greatly. Unemployment and disability have both been found to contribute to lower self-esteem, likely because of the impact they have on a person’s sense of independence, social identity, and perceived ability to contribute (von Soest et al., 2018).

On the brighter side, certain personality traits can buffer these effects. For example, people who display a more mature personality and emotional stability tend to enjoy higher self-esteem (von Soest et al., 2018). These individuals often have better coping mechanisms, a balanced view of their strengths and weaknesses, and the resilience needed to face life’s challenges without excessive self-blame.

Finally, societal attitudes about our bodies and fitness habits also play a major role. Social norms—like how much weight we place on others’ opinions about our appearance and lifestyle—are often linked negatively with self-esteem, particularly when people feel they don’t measure up (Chang & Suttikun, 2017). However, having a strong sense of self-efficacy about exercise and pursuing physical activities for self-fulfillment rather than social approval can boost self-esteem.

Taken together, these factors show us that self-esteem is not a simple switch we can flip on or off. It is deeply embedded in our life circumstances, relationships, identities, and even the subtle ways we see and care for ourselves. Understanding these influences is the first step toward creating environments—at home, at work, and in society—that nurture and protect our sense of worth.

The Effects of Social Media on Self-Esteem:

By now, many people won’t be surprised to hear that spending too much time scrolling through social media can damage how we feel about ourselves. Research supports this common observation, showing that social media use is frequently linked to lower self-esteem (Friedlander, 2016). But why does something designed to keep us connected often leave us feeling worse instead of better?

To understand this, we need to remember a basic truth about human beings: we are social by nature. We thrive on connection, interaction, and community. At the same time, we instinctively compare ourselves to the people around us—gauging our progress, our appearance, our success, and even our happiness in relation to what we see in others. This tendency isn’t new; it’s part of being human. What is new is how much fuel social media adds to this comparison fire.

Before the age of Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok, our comparisons were mostly limited to people we saw regularly—family, friends, coworkers, neighbors. But now, with a few taps on a screen, we have an endless stream of carefully curated images and updates from friends, acquaintances, celebrities, influencers, and strangers from all over the world.

The problem is that what we see online is rarely the full truth. Instead, social media feeds are highlight reels. We see glowing vacation photos, exciting life updates, polished selfies, and celebratory milestones. What we don’t see are the messy parts—failures, disappointments, insecurities, or the ordinary moments when nothing noteworthy is happening.

When we compare our unfiltered reality to someone else’s filtered highlights, it’s no surprise that our own life can start to look dull or lacking by comparison. This gap between what we see online and what we feel day-to-day can quietly chip away at our self-esteem. We start to wonder: Am I falling behind? Why isn’t my life as beautiful or successful as theirs?

However, the impact of social media on our self-esteem isn’t all doom and gloom. The truth is, social media itself isn’t inherently bad for us—it’s how we use it, and how mindfully we interpret what we see, that matters most.

If we use social media in moderation, stay aware that we’re only seeing the highlight reels, and remind ourselves that every person has struggles and flaws behind the scenes, we can protect our sense of self-worth. In fact, we might even flip the script: when used wisely, social media can inspire us, connect us with like-minded people, or motivate us to pursue our goals.

So, you don’t have to swear off Instagram or delete your Facebook profile to maintain healthy self-esteem. Instead, use these platforms consciously and keep your perspective grounded. When you catch yourself spiraling into unhealthy comparison, pause and remember: what you see is only part of the story—never the whole picture (Friedlander, 2016).

Tips & Affirmations for Enhancing Self-Esteem:

When we think of self-esteem as something that can grow and strengthen—like a muscle—we open up a whole new world of possibilities for ourselves. It reminds us that we aren’t stuck with the same old self-image forever. Just as muscles grow stronger with regular exercise and care, so too can our sense of worth and self-respect.

Here are the practical tips you can start using right away to help build up healthier self-esteem:

- Spend time with people who lift you up: Surround yourself with those who encourage you, believe in you, and bring out your best self.

- Give back by helping others: Acts of kindness can make you feel useful and valued—whether that’s volunteering, lending a hand to a neighbor, or simply being there for a friend.

- Celebrate your achievements, no matter how small: Every step forward counts. Acknowledge your wins—big or small—and remind yourself they matter.

- Do what makes you happy: Prioritize activities that make you feel alive and fulfilled, whether that’s painting, hiking, cooking, or dancing in your living room.

- Change what you can—and let go of what you can’t: Focus your energy on what’s within your control. Worrying about things you can’t change drains your self-worth and motivation.

- Release the grip of perfectionism: Nobody is perfect, and chasing perfection will only exhaust you. Give yourself permission to be human—flaws and all.

- Speak to yourself like a friend: If you wouldn’t say something to your best friend, don’t say it to yourself. Be gentle, kind, and encouraging in your self-talk.

- Get involved in activities outside your usual routine: Join a club, take up a hobby, or learn something new—these can broaden your confidence and help you connect with new people.

- Own your uniqueness: Your quirks, your experiences, and your perspective are what make you, you. Embrace what sets you apart.

- Create a positive self-dialogue: Be mindful of the words you say to yourself daily—turn them into words that empower you rather than tear you down.

The well-known American author and motivational coach Jack Canfield once put it perfectly: “Daily affirmations are to the mind what exercise is to the body.” In other words, repeating positive statements about yourself every day helps train your mind to see your value and believe in your strengths.

If you’re not sure where to start, here are the simple affirmations from Develop Good Habits that can help boost your self-esteem and overall well-being:

- Mistakes are stepping stones to success. They are the path I must tread to achieve my dreams.

- I will continue to learn and grow.

- Mistakes are just an apprenticeship to achievement.

- I deserve to be happy and successful.

- I deserve a good life. I deny any need for suffering and misery.

- I am competent, smart, and able.

- I am growing and changing for the better.

- I love the person I am becoming.

- I believe in my skills and abilities.

- I have great ideas. I make useful contributions.

- I acknowledge my own self-worth; my self-confidence is rising.

- I am worthy of all the good things that happen in my life.

- I am confident with my life plan and the way things are going.

- I deserve the love I am given.

- I let go of the negative feelings about myself and accept all that is good.

- I will stand by my decisions. They are sound and reasoned.

- I have, or can quickly get, all the knowledge I need to succeed.

If none of these feel quite right for you, don’t worry—feel free to create your own! When you do, keep these three simple affirmation guidelines in mind:

- Use the present tense: Affirmations should reflect who you are right now. For example, instead of saying “I will do better tomorrow,” try “I am doing my best today.”

- Keep them positive: Focus on what you are, not what you’re not. So rather than “I am not a failure,” say “I am worthy and capable.”

- Make them genuine and meaningful: Your affirmations should resonate with you. They should feel true to your life and who you are, or who you are becoming.

Use these tips and affirmations daily—say them out loud, write them down, repeat them in your mind. Over time, you’ll find that they help strengthen your “self-esteem muscle,” empowering you to see yourself in a more positive, accepting light each day.

Quotes on Self-Esteem:

Sometimes, all it takes to ignite the journey of self-love is a few words that speak straight to the heart. Quotes might seem simple, but they can hold immense power—especially when they echo exactly what you need to hear at just the right moment. Not every quote will resonate with everyone, but chances are, at least one of these might plant a seed of change or light a spark of self-compassion within you.

Here are some timeless quotes to remind you of your worth, your wholeness, and your right to feel good about who you are:

“You yourself, as much as anybody in the entire universe, deserve your love and affection.” — Sharon Salzberg

This gentle reminder from Sharon Salzberg, a pioneer in loving-kindness meditation, tells us that we are just as worthy of our own love as anyone else is.

“The greatest thing in the world is to know how to belong to oneself.” — Michel de Montaigne

Centuries ago, Montaigne understood that self-belonging is the root of all freedom. When you truly belong to yourself, no one can take that away.

“The man who does not value himself, cannot value anything or anyone.” — Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand reminds us that self-value is the foundation for how we relate to the world. If we can’t see our own worth, it becomes much harder to appreciate the worth of others.

“Dare to love yourself as if you were a rainbow with gold at both ends.” — Aberjhani

This vivid image from Aberjhani invites you to treat yourself as something magical and precious—worth seeking, worth protecting, worth loving fully.

“As long as you look for someone else to validate who you are by seeking their approval, you are setting yourself up for disaster. You have to be whole and complete in yourself. No one can give you that. You have to know who you are—what others say is irrelevant.” — Nic Sheff

Nic Sheff’s words are a wake-up call: your wholeness does not lie in someone else’s hands. It is already yours to claim.

“I don’t want everyone to like me; I should think less of myself if some people did.” — Henry James

Henry James reminds us that universal approval isn’t a badge of honor—sometimes, staying true to yourself means not pleasing everyone, and that’s okay.

“Remember, you have been criticizing yourself for years and it hasn’t worked. Try approving of yourself and see what happens.” — Louise L. Hay

Louise Hay, a pioneer in self-help and affirmations, turns the usual cycle on its head: if self-criticism hasn’t brought you happiness yet, maybe it’s time to try self-acceptance instead.

“Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be?” — Marianne Williamson

One of Marianne Williamson’s most famous reflections urges us to stop shrinking from our own greatness. You are allowed to shine.

“I don’t entirely approve of some of the things I have done, or am, or have been. But I’m me. God knows, I’m me.” — Marianne Williamson

In another quote, Williamson reminds us that self-acceptance does not require perfection. We are all a work in progress, and that’s enough.

“To me, self-esteem is not self-love. It is self-acknowledgement, as in recognizing and accepting who you are.” — Amity Gaige

Amity Gaige draws an important line here: self-esteem doesn’t mean blindly adoring yourself—it means seeing yourself clearly, flaws and all, and choosing to stand with yourself anyway.

“Self-esteem is as important to our well-being as legs are to a table. It is essential for physical and mental health and for happiness.” — Louise Hart

This quote from Louise Hart reminds us that self-esteem is not a luxury—it’s a core pillar of our stability, just like the legs holding up a table.

“Self-esteem is made up primarily of two things: feeling lovable and feeling capable. Lovable means I feel people want to be with me. They invite me to parties; they affirm I have the qualities necessary to be included. Feeling capable is knowing that I can produce a result. It’s knowing I can handle anything that life hands me.” — Jack Canfield

Jack Canfield breaks self-esteem down into something practical and clear: it’s about feeling worthy of love and believing you can handle life’s challenges.

“You can’t let someone else lower your self-esteem, because that’s what it is—self-esteem. You need to first love yourself before you have anybody else love you.” — Winnie Harlow

Model and activist Winnie Harlow’s words cut to the truth—no one has the power to lower your self-worth unless you hand it to them.

“A man cannot be comfortable without his own approval.” — Mark Twain

Mark Twain puts it simply: true comfort in life begins with accepting yourself.

“Our self-respect tracks our choices. Every time we act in harmony with our authentic self and our heart, we earn our respect. It is that simple. Every choice matters.” — Dan Coppersmith

Dan Coppersmith reminds us that our self-esteem isn’t a one-time decision—it’s built every day through our actions. Each choice is a chance to strengthen it.

In conclusion, self-esteem is not just a concept tucked away in psychology textbooks—it’s an everyday, living part of how we see ourselves and navigate the world around us. It shapes how we speak to ourselves in quiet moments, how we bounce back when life knocks us down, and how we connect with those around us.

It’s true that healthy self-esteem won’t erase every challenge, but it will give you a stronger foundation to face those challenges with courage and self-compassion. It’s a resource you can grow over time—step by step, moment by moment—through conscious effort, reflection, and sometimes the support of others.

So stay kind to yourself, stay curious about your thoughts, and remember that the work you do to build your self-esteem today can ripple outwards, inspiring the people you love to see their own worth too.

There may never be one perfect formula for “how much” self-esteem is just right, but maybe that’s the point—it’s less about reaching a finish line and more about living your life as fully and authentically as you can. Keep going. You’re worth it.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Can self-esteem really change over time?

Yes—self-esteem is not a fixed trait but a dynamic aspect of who you are. It evolves throughout your life depending on your experiences, mindset, and environment. Major life events such as success at work, healthy relationships, or supportive communities can strengthen your sense of self-worth. On the other hand, criticism, failure, neglect, or toxic relationships can lower it. The good news is that self-esteem can always be nurtured—through intentional habits, positive self-talk, therapy, setting achievable goals, and learning to see setbacks as opportunities for growth rather than proof of inadequacy.

What’s the difference between high self-esteem and arrogance?

This is a common question. Healthy self-esteem means you respect yourself, acknowledge your strengths and weaknesses, and believe you have value—just like everyone else does. It does not mean you think you’re better than others. Arrogance, by contrast, often comes from insecurity and is about trying to feel superior by putting others down. People with genuine self-esteem tend to be humble, open to feedback, and supportive of others’ success, whereas arrogance seeks validation through comparison. Remember: true self-esteem lifts you up without pushing others down.

Can parents really help build their children’s self-esteem?

Definitely. Parents, caregivers, and teachers play a critical role in shaping a child’s self-esteem from an early age. Kids learn self-worth from the way adults respond to their mistakes, efforts, and feelings. Praising effort rather than perfection, encouraging problem-solving, listening without harsh judgment, setting healthy boundaries, and showing unconditional love all help children develop a secure sense of self-worth. It’s also important for adults to model self-compassion themselves—children often copy what they see more than what they’re told.

Does therapy really help with low self-esteem?

Yes, therapy and counseling can be transformative for people struggling with low self-esteem. Skilled therapists create a safe, accepting space for clients to explore the root causes of their self-criticism and negative beliefs. Through approaches like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), clients learn to recognize distorted thinking patterns, challenge unrealistic expectations, and build healthier beliefs about themselves. Over time, this can replace a harsh inner critic with a kinder, more supportive inner voice. For many, therapy also provides new, positive relational experiences that help heal old wounds.

Are there quick ways to boost self-esteem day to day?

Long-term self-esteem growth takes time, but daily actions can make a real difference. Simple steps include practicing daily affirmations that remind you of your worth, setting realistic goals and celebrating progress, spending time doing activities that make you feel capable and happy, and using compassionate self-talk instead of harsh self-criticism. Even small wins—like finishing a task, going for a walk, or speaking up for yourself—build confidence and reinforce the belief that you are capable and worthy.

How does social media affect self-esteem?

Social media can be a double-edged sword for self-esteem. On one hand, it can help you connect, learn, and find inspiration. On the other, it makes constant comparison almost unavoidable. People tend to share highlight reels, not everyday struggles—leading us to think others are happier, more attractive, or more successful than they really are. This can feed feelings of inadequacy or “not being enough.” The key is mindful use: unfollow accounts that make you feel worse about yourself, follow positive or authentic ones instead, and remind yourself that what you see is rarely the whole story.

What are good daily habits to build and maintain healthy self-esteem?

There are many simple habits you can weave into your daily life to strengthen self-esteem. Examples include:

- Practice gratitude: Keep a journal or pause each day to note things you appreciate about yourself and your life.

- Celebrate your achievements: Acknowledge small successes instead of dismissing them.

- Do activities you enjoy: Make time for hobbies, creativity, or relaxing moments that remind you of your worth.

- Surround yourself with supportive people: Spend time with those who lift you up, encourage you, and accept you as you are.

- Move your body: Regular exercise—even gentle walks—boosts mood and self-image.

- Use positive self-talk: Notice your inner critic and actively replace harsh thoughts with kinder, realistic ones.

- Set healthy boundaries: Learn to say no and prioritize your needs.

- Try something new: Stepping out of your comfort zone, even in small ways, builds confidence and shows you what you’re capable of.

References:

- Adler, N., & Stewart, J. (2004). Self-esteem. Psychosocial Working Group. Retrieved from http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/selfesteem.php

- Allegiance Health. (2015). 8 Health benefits of a healthy self-esteem. Health & Wellness Blog. Retrieved from https://www.allegiancehealth.org/blog/women/8-health-benefits-healthy-self-esteem

- Bastianello, M., Pacico, J., & Hutz, C. (2014). Optimism, self-esteem and personality: Adaptation and validation of the Brazilian Version Of The Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R). Psico-USF, Bragança Paulista. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pusf/v19n3/15.pdf

- Branden, N. (1992). The power of self-esteem. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B09VWP2TN1/

- Branden, N. (2013). What self-esteem is and is not. Retrieved from http://www.nathanielbranden.com/what-self-esteem-is-and-is-not

- Bingham, W. C. (1983). Problems in the assessment of self-esteem. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 6, 17-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00118849

- Brockner, J. 1984. Low self-esteem and behavioral plasticity: Some implications for personality and social psychology. In L. Wheeler (Ed.), Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 37: 1732–1741.

- Burton, N. (2015). Self-confidence versus self-esteem. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201510/self-confidence-versus-self-esteem

- Chang, H. J., & Suttikun, C. (2017). The examination of psychological factors and social norms affecting body satisfaction and self-esteem for college students. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 45(4), 422-437. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12220

- Chen, S. X., Cheung, F. M., Bond, M. H., & Leung, J. (2006). Going beyond self-esteem to predict life satisfaction: The Chinese case. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 9, 24-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2006.00182.x

- Confidence Coalition. (n.d.). Join KD in the movement to build confidence in girls and women. Kappa Delta Sorority. Retrieved from https://kappadelta.org/initiatives/confidence-coalition/

- Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Image and self-esteem. Mentor Resource Center. Retrieved from http://mentor-center.org/image-and-self-esteem/

- Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2003). Seeking self-esteem: Construction, maintenance, and protection of self-worth.

- Davis, W., Gfeller, K., & Thaut, M. (2008). An introduction to music therapy. Silver Spring, MD: American Music Therapy Association. https://www.amazon.com/dp/1884914209/

- Demo, D. H. (1985). The measurement of self-esteem: Refining our methods. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1490-1502. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.6.1490

- Diener, E. & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.653

- Dumont, M. & Provost, M. A,. (1999). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28, 343-363. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021637011732

- Dove Self-Esteem Fund. (2008). Real girls, real pressure: A national report on the state of self-esteem. Dove. Retrieved from http://www.isacs.org/misc_files/SelfEsteem_Report%20-%20Dove%20Campaign%20for%20Real%20Beauty.pdf

- Edberg, H. (2013). How to improve your self-esteem: 12 Powerful tips. The Positivity Blog. Retrieved from https://www.positivityblog.com/improve-self-esteem/

- Ellis, A. (1994). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. Birch Lane Press. https://www.amazon.com/dp/1559722487/

- Ellis, A. (1976). RET abolishes most of the human ego. Psychotherapy: Theory, research & practice, 13(4), 343. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086502

- Friedlander, J. (2016). Why social media is ruining your self-esteem—and how to stop it. Success. Retrieved from https://www.success.com/article/why-social-media-is-ruining-your-self-esteem-and-how-to-stop-it

- Gilbertson, T. (2016). Does therapy for low self-esteem really work? Good Therapy. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/does-therapy-for-low-self-esteem-really-work-0520164

- Grogan, S. (1999). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. London, UK: Routledge. https://www.amazon.com/dp/0415147859/

- Grohol, J. M. (2011). 6 Tips to improve your self-esteem. Psych Central. Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/blog/6-tips-to-improve-your-self-esteem/

- Hibbert, C. (2013). Self-esteem vs. self-worth: Q & A with Dr. Christina Hibbert. Retrieved from http://www.drchristinahibbert.com/self-esteem-vs-self-worth/

- Karatas, Z., & Cakar, F. S. (2011). Self-esteem and hopelessness, and resiliency: An exploratory study of adolescents in Turkey. International Education Studies, 4(4), 84-91. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1066570

- Kernis, M. H., & Lakey, C. E. (2010). Fragile versus secure high self-esteem: Implications for defensiveness and insecurity. Psychology Press.

- King, K. A., Vidourek, R. A., Davis, B., & McClellan, W. (2009). Increasing self-esteem and school connectedness through a multidimensional mentoring program. Journal of School Health, 72, 294-299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb01336.x

- Laurinavicius, T. (2017). 11 Research-backed hacks to improve self-confidence. Entrepreneur. Retrieved from https://www.entrepreneur.com/slideshow/302265

- MacInnes, D. L. (2006). Self‐esteem and self‐acceptance: an examination into their relationship and their effect on psychological health. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 13(5), 483-489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00959.x

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396. https://talkcurriculum.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/maslow-a-1943-a-theory-of-human-motivation.pdf

- McLeod, S. (2008). Self concept. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/self-concept.html

- McLeod, S. (2017). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

- Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (1995). Who is happy?. Psychological science, 6(1), 10-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00298.x

- Misetich, M., & Delis-Abrams, A. (2003). Your self esteem is up to YOU. Self-Growth. Retrieved from http://www.selfgrowth.com/articles/Abrams1.html

- Neff, K. (n.d.). Why self-compassion is healthier than self-esteem. Self-Compassion.org. Retrieved from http://self-compassion.org/why-self-compassion-is-healthier-than-self-esteem/

- Neill, J. (2005). Definitions of various self constructs. Wilderdom. Retrieved from http://www.wilderdom.com/self/

- Orth, U. (2018). The family environment in early childhood has a long-term effect on self-esteem: A longitudinal study from birth to age 27 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114, 637-655. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000143

- Park, K. M., & Park, H. (2014). Effects of self-esteem improvement program on self-esteem and peer attachment in elementary school children with observed problematic behaviors. Asian Nursing Research, 9, 53-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2014.11.003

- Purkey, W. (1988). An overview of self-concept theory for counselors. ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Personnel Services. Ann Arbor: MI (An ERIC/CAPS Digest: ED304630). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED304630

- Reitzes, D. C., & Mutran, E. J. (1994). Multiple roles and identities: Factors influencing self-esteem among middle-aged working men and women. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 313-325. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787158

- Reitzes, D. C., & Mutran, E. J. (2006). Self and health: Factors that encourage self-esteem and functional health. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(1), S44-S51. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.1.S44

- Robinson, J., Shaver, P., & Wrightsman, L. (2010). Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. https://www.amazon.com/dp/0125902441/

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. https://www.amazon.com/dp/069162268X/

- Self Esteem Awareness. (n.d.). 10 Positive self esteem examples. Retrieved from https://www.selfesteemawareness.com/10-positive-self-esteem-examples/

- Seligman, M. (2006). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. New York, NY: Vintage Books. https://www.amazon.com/dp/1400078393/

- Smith, S. R., & Harte, V. (n.d.). 10 Characteristics of people with high self-esteem. Dummies. Retrieved from http://www.dummies.com/health/mental-health/self-esteem/10-characteristics-of-people-with-high-self-esteem/

- Spencer, J., Zimet, G., Aalsma, M., & Orr, D. (2002). Self-esteem as a predictor of initiation of coitus in early adolescents. Pediatrics, 109, 581-584. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.109.4.581

- Von Soest, T., Wagner, J., Hansen, T., & Gerstorf, D. (2018). Self-esteem across the second half of life: The role of socioeconomic status, physical health, social relationships, and personality factors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114, 945-958. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000123

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College