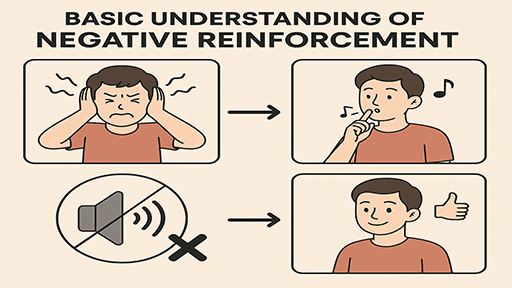

Basic Understanding of Negative Reinforcement:

When we think about changing behavior, the first ideas that usually come to mind are rewards and punishments. However, there’s a lesser-understood concept that plays a significant role in shaping our actions every day: negative reinforcement. Often confused with punishment, negative reinforcement works in a completely different way — instead of adding an unpleasant consequence, it removes something undesirable to strengthen a behavior. Imagine the relief of silencing a blaring alarm clock by getting out of bed — that simple action is a classic example. From encouraging children to do their homework, to motivating employees, to training pets, negative reinforcement quietly influences countless decisions in our daily lives. But how does it really work, and is it always the best approach? In the rest of this article, we will explore the basic understanding of negative reinforcement, clears up common misconceptions, and explores when it can help — and when it might backfire.

Defining Negative Reinforcement:

Negative reinforcement is a fundamental concept within B. F. Skinner’s (1938) theory of operant conditioning — a framework that explains how consequences shape voluntary behavior. Unlike punishment, which aims to decrease unwanted behaviors by introducing an unpleasant outcome, negative reinforcement works by increasing the likelihood that a behavior will occur again. It does this by removing an aversive or undesirable stimulus immediately after the desired behavior is performed (Skinner, 1938).

To illustrate, imagine someone suffering from a headache who takes pain medication. The unpleasant stimulus — the headache — is removed once the medication takes effect. This relief strengthens the behavior of taking medication in the future whenever pain arises (Bouton, 2007). In this way, the removal of discomfort acts as a motivator, reinforcing the behavior that caused its removal.

The Science Behind Negative Reinforcement:

At its core, negative reinforcement is about the brain’s natural drive to seek relief from discomfort. Neurologically, when an unpleasant stimulus is removed, the brain registers this relief as rewarding. This process involves several brain structures and neurotransmitters that play key roles in learning and motivation. The dopaminergic system, which governs reward pathways, works alongside the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex to help the brain learn which actions help avoid or remove unpleasant experiences (Schultz, 2016).

A related concept is avoidance learning, which is a specific type of negative reinforcement. In avoidance learning, an individual learns to perform certain behaviors to prevent an unpleasant situation before it happens. For instance, an employee might complete tasks ahead of a deadline to avoid last-minute stress and criticism from a supervisor (Mowrer, 1951). This avoidance removes the anticipated stressor, reinforcing the behavior of working early.

Negative Reinforcement in Operant Conditioning:

Skinner’s (1965) broader operant conditioning theory emphasizes how behaviors are shaped by their consequences. According to this framework, behaviors followed by positive outcomes tend to be repeated, while those followed by negative outcomes are less likely to recur. Negative reinforcement fits into this model by showing how the removal of a negative condition strengthens behavior.

Domjan (2006) highlights that negative reinforcement, unlike punishment, increases the frequency of a behavior precisely because it allows the individual to escape or avoid something unpleasant. Whether it’s turning off a loud alarm by getting out of bed or leaving a noisy room to regain peace, negative reinforcement shapes our daily habits, work routines, and even major life choices by motivating actions that bring relief from discomfort.

So, negative reinforcement is far more than just a classroom theory — it’s an everyday force influencing how people and animals learn to navigate their environments, minimize discomfort, and repeat behaviors that help them do so.

Negative Reinforcement vs. Punishment:

Negative reinforcement and punishment are two of the most commonly misunderstood concepts in behavior management, yet they operate in fundamentally different ways. While both are tools for influencing behavior, they achieve their effects through opposite mechanisms.

Negative reinforcement works by strengthening a behavior through the removal of an unpleasant stimulus. For instance, leaving the house early to avoid getting stuck in traffic removes the stress of a traffic jam — which, in turn, reinforces the habit of leaving early. Punishment, on the other hand, aims to reduce or suppress a behavior by introducing an aversive consequence. For example, receiving a fine for speeding is designed to discourage future speeding. Understanding how these processes differ is essential for anyone trying to shape behavior effectively and ethically.

Pros and Cons of Negative Reinforcement:

Advantages:

When used thoughtfully, negative reinforcement can be an effective tool for encouraging desirable behaviors and reducing problematic ones. Research by Athens and Vollmer (2010) found that negative reinforcement strategies can significantly boost compliance with tasks and help reduce disruptive behaviors in various settings.

Interestingly, negative reinforcement can also have surprising emotional benefits. Xu et al. (2021) discovered that individuals exposed to negative reinforcement reported higher levels of positive affect and joviality, along with lower fatigue, compared to those exposed to other types of reinforcement. This suggests that the relief from an unpleasant stimulus can actually uplift mood and motivation.

In educational settings, negative reinforcement can help students master new skills. Iwata (1987) showed that removing an aversive stimulus — for example, allowing a student to take a break after completing a difficult task — can motivate learners to engage more actively and correctly, thereby reinforcing positive academic behaviors.

Disadvantages:

Despite these advantages, negative reinforcement is not without its pitfalls. One major risk is that it can unintentionally encourage avoidance rather than true problem-solving. Piazza et al. (1997) demonstrated that when individuals discover they can escape or avoid unpleasant tasks by acting out, the avoidance behavior itself becomes reinforced — often worsening the problem over time.

Behaviors maintained through negative reinforcement can also be particularly resistant to change. For example, Iwata (1987) found that when escape behaviors become entrenched, interventions must be carefully designed to avoid accidentally reinforcing the very behaviors they aim to eliminate. A classic scenario is a student who throws a tantrum to get out of doing an assignment: if the teacher removes the task to stop the tantrum, the student learns that misbehavior is an effective escape strategy — and is likely to repeat it.

Additionally, negative reinforcement can sometimes clash with positive reinforcement approaches, complicating behavior plans. Lalli et al. (1999) compared positive and negative reinforcement and found that they can compete with each other, reducing the overall effectiveness of treatment strategies for behaviors like task avoidance. In such cases, using well-planned positive reinforcement may be the more effective and sustainable option.

Pros and Cons of Punishment:

Advantages:

Punishment, when applied correctly, can bring about rapid decreases in unwanted behaviors. Hanley et al. (2005) demonstrated that functional communication training paired with punishment was more effective at reducing severe problem behaviors than training without punishment.

Interestingly, some individuals and caregivers prefer interventions that include punishment elements. The same study by Hanley et al. (2005) found that participants managing severe behavior problems often favored treatment plans that included mild punishment, as they led to quicker, more noticeable results.

Disadvantages:

However, the use of punishment is fraught with ethical, legal, and practical concerns. Decades ago, the Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights raised important questions about the moral implications of behavior modification, highlighting the risk of infringing on individual rights (Whitman, 1974).

Punishment-based methods can also cause unintended psychological harm. A national survey by Reed and Lovett (2007) found widespread disagreement among professionals about the ethics and effectiveness of punishment, with concerns about negative side effects, such as emotional distress.

Overreliance on punishment can make it less effective over time and may lead to harmful consequences. Chen (2023) noted that excessive punishment can erode an individual’s sense of autonomy, damage trust, and cause resentment or fear. Similarly, Bangash et al. (2024) emphasized that the misuse of punishment can foster feelings of anger, anxiety, or defiance in those subjected to it.

Finding the Balance:

In practice, both negative reinforcement and punishment can shape behavior — but each must be used carefully, ethically, and with a clear understanding of how they work. Where negative reinforcement removes discomfort to strengthen desired actions, punishment adds discomfort to suppress unwanted ones. Knowing when and how to apply these strategies — and being mindful of their limitations — is key to promoting lasting, positive change in behavior.

Negative Reinforcement vs. Positive Reinforcement:

Negative reinforcement and positive reinforcement are two fundamental strategies used to strengthen desired behaviors — but they achieve this goal through different mechanisms. Understanding how each works is crucial for anyone involved in teaching, parenting, management, or behavior modification.

Positive reinforcement works by adding a rewarding stimulus after a behavior occurs, making it more likely that the behavior will be repeated. Classic examples include giving a child praise for doing their homework, offering an employee a bonus for meeting a target, or rewarding a pet with a treat for following a command. The added reward creates a pleasant association with the behavior, encouraging its repetition (Evans, 2015).

Negative reinforcement, on the other hand, strengthens behavior by removing an unpleasant or aversive stimulus once the desired behavior is performed. A simple example is turning off a loud alarm after getting out of bed, or stopping nagging once a child finishes their chores. The relief from something unpleasant reinforces the action that caused the discomfort to stop (Evans, 2015).

Both approaches fall under the umbrella of operant conditioning, yet they tap into different motivational systems: positive reinforcement motivates through gain, while negative reinforcement motivates through relief from discomfort.

Why Combine Positive and Negative Reinforcement?

Research shows that combining positive and negative reinforcement can be a powerful strategy for encouraging desired behaviors more effectively than using either method alone. For example, Bouxsein et al. (2011) found that pairing the two reinforcement types can improve learning outcomes and task compliance, especially when tasks are time-sensitive or challenging. Similarly, Wergård et al. (2015) highlighted that using both forms together can create a balanced dynamic of motivation and relief, helping individuals stay engaged and more willing to complete tasks.

Pairing the two strategies also allows for flexibility: people respond differently to rewards and the removal of unpleasant conditions. Using both approaches increases the chances that at least one form of reinforcement will resonate and drive the desired behavior.

Real-World Applications:

Combining positive and negative reinforcement happens more often than we may realize — and it can be especially useful in everyday settings like classrooms, workplaces, and families.

In the classroom, for instance, a teacher might praise a student for turning in assignments on time (positive reinforcement) and also remove extra homework for consistently good behavior (negative reinforcement). The student is motivated both by the reward of praise and the relief of less work.

In the workplace, managers often use similar pairings. An employee might earn a financial bonus for exceeding sales targets (positive reinforcement) and be excused from weekly check-in meetings once they demonstrate consistent performance and reliability (negative reinforcement). The combination of an added benefit and the removal of an obligation reinforces the high performance.

In parenting, caregivers can reinforce good behavior by giving extra playtime when chores are completed (positive reinforcement) while also removing a disliked responsibility — like washing dishes — for a child who keeps their room clean all week (negative reinforcement). The child is encouraged to keep up the good habits through both the promise of something enjoyable and the relief from an unwanted task.

Putting It All Together:

While positive and negative reinforcement use different pathways to strengthen behavior, they both aim to achieve the same outcome: to make desired actions more likely to occur again. By understanding how each works — and how they can be used together — parents, teachers, and managers can create environments that motivate, engage, and support the people they guide every day. Combining the motivating power of rewards with the relief of removing unwanted conditions can be an especially effective way to build healthy habits and positive behaviors that last.

How Effective Is Negative Reinforcement?

Negative reinforcement is a well-established tool in the field of behavior modification, with a significant body of research supporting its effectiveness — particularly in applied and educational settings. By definition, negative reinforcement strengthens a desired behavior by removing an aversive stimulus once that behavior occurs, thereby increasing the likelihood that the behavior will be repeated.

Iwata (1987) provided early foundational insights into how behaviors maintained through negative reinforcement can be shaped by strategically removing unpleasant stimuli. For example, when a student is allowed to take a break after completing a difficult task, the removal of the aversive condition (the challenging work) reinforces the act of completing it.

However, research comparing different reinforcement methods suggests that negative reinforcement is not always the best stand-alone solution. Lalli et al. (1999) found that positive reinforcement — adding a rewarding stimulus rather than removing an unpleasant one — can be even more effective in reducing certain problem behaviors. They argued that positive reinforcement tends to encourage active participation and skill building, while negative reinforcement may inadvertently encourage avoidance. Piazza et al. (1996) expanded on this, suggesting that a balanced approach integrating both positive and negative reinforcement often produces the best results, providing both motivation and relief.

That said, it’s important to remember that negative reinforcement, if misapplied, can sometimes strengthen the very behaviors we want to reduce — especially if escape or avoidance becomes a convenient way for someone to cope with tasks they find unpleasant.

Advantages of Negative Reinforcement:

Despite its potential drawbacks, negative reinforcement has clear and proven advantages. For example, Athens and Vollmer (2010) found that using negative reinforcement strategies in classrooms significantly increased students’ compliance with tasks while reducing disruptive behaviors. By removing an aversive consequence, such as persistent requests or demands, teachers could encourage students to complete work willingly.

Negative reinforcement can also lead to rapid behavior change. Lerman and Iwata (1996) demonstrated that when an unpleasant stimulus is quickly removed following a desired behavior, individuals are more likely to repeat that behavior. This is why negative reinforcement is commonly used in educational and therapeutic contexts where immediate results are sometimes necessary to maintain engagement.

Beyond schools and therapy, negative reinforcement can play a positive role in workplaces as well. For instance, Piazza et al. (1997) reported that employees who experienced fewer criticisms or micromanagement when they met deadlines were more likely to maintain high levels of productivity. Here, the removal of a negative factor — performance-related criticism — acted as a reinforcer for timely, efficient work.

Disadvantages of Negative Reinforcement:

However, relying too heavily on negative reinforcement can backfire. One risk is that it may encourage avoidance instead of genuine engagement with tasks. Mowrer’s (1951) research on avoidance learning showed that when people consistently use avoidance to escape unpleasant experiences, they may not learn how to solve the underlying problem. This tendency can hinder the development of long-term coping or problem-solving skills.

Another challenge is that behaviors sustained by negative reinforcement can be difficult to replace with more adaptive behaviors. Iwata (1987) noted that when people or students learn to escape tasks through certain behaviors — such as acting out to avoid homework — those behaviors can become deeply ingrained, requiring thoughtful, consistent intervention to change.

Finally, overusing negative reinforcement can have emotional costs. Hammond et al. (2020) found that individuals frequently exposed to negative reinforcement in learning environments may experience heightened stress and anxiety. This can undermine performance, motivation, and overall well-being — especially when negative reinforcement is not balanced with positive reinforcement strategies that build confidence and intrinsic motivation.

A Step-By-Step Guide for Using Negative Reinforcers Effectively:

While negative reinforcement can be a valuable tool for shaping behavior, it must be applied thoughtfully and systematically to achieve the desired results without causing unintended side effects. Research and practical guidelines suggest that following a clear, structured approach helps maximize its benefits while minimizing risks (Huitt, 1994; Iwata, 1987; Miltenberger, 2016). Below is a detailed, human-like explanation of each step to help parents, teachers, managers, or therapists use negative reinforcement effectively and ethically.

Step 1: Define the Target Behavior: The first step is to clearly identify the specific behavior you want to increase. This behavior should be measurable and observable — vague goals like “be more responsible” won’t work. For example, instead of saying “improve homework habits,” define the behavior as “completes math assignments before 8 PM every school night.” Being precise allows you to track progress accurately and make adjustments as needed (Huitt, 1994).

Step 2: Identify the Aversive Stimulus: Next, pinpoint the specific stimulus the person finds unpleasant and is motivated to escape or avoid. This could be anything from nagging, extra chores, or an annoying noise, to an unappealing task. For negative reinforcement to work, the aversive condition must genuinely be something the person wants to get rid of — otherwise, its removal won’t act as a motivator (Iwata, 1987).

Step 3: Make the Removal Contingent on the Desired Behavior: It’s crucial that the unpleasant stimulus is only removed after the desired behavior occurs. If the aversive condition goes away regardless of whether the behavior happens, the reinforcement link is broken and the strategy won’t work. For example, only stop reminding a student about chores once they actually complete them — not before (Miltenberger, 2016).

Step 4: Introduce the Negative Reinforcer Gradually and Consistently: Remove the aversive stimulus in a controlled and intentional way. Avoid removing it too quickly or inconsistently, as this can weaken the behavior change you’re trying to establish. A gradual reduction helps the person build a stable pattern of the desired behavior. For example, if you use extra homework as the aversive stimulus, reduce the workload gradually as the student consistently meets performance goals (Huitt, 1994).

Step 5: Monitor and Evaluate the Behavior: Keep a close eye on whether the target behavior is actually increasing. Observe and record progress so you can tell if the negative reinforcement is working as intended. If you see little or no improvement, reassess the unpleasant stimulus — maybe it’s not aversive enough — or adjust how and when it’s removed. Sometimes, a small tweak can make a big difference (Iwata, 1987).

Step 6: Pair Negative Reinforcement with Positive Reinforcement: While negative reinforcement can jump-start behavior change, combining it with positive reinforcement often produces the best long-term results. Once the desired behavior becomes more consistent, start pairing the removal of the aversive stimulus with rewards like praise, privileges, or small incentives. For example, when a student turns in work on time to avoid extra tasks, also praise their effort to build intrinsic motivation and positive feelings about the behavior (Miltenberger, 2016).

Step 7: Maintain Balance to Avoid Stress: Finally, don’t rely solely on negative reinforcement. Overusing aversive conditions can create a stressful or anxiety-provoking environment, which can backfire and lead to avoidance or resentment. A healthy balance of positive and negative reinforcement keeps motivation high and helps maintain a supportive, productive atmosphere (Huitt, 1994).

By following these seven practical steps — clearly defining the behavior, choosing the right aversive stimulus, ensuring consistent removal, monitoring progress, and balancing reinforcement strategies — negative reinforcement can become a powerful, ethical, and effective tool for encouraging positive behavior change.

Common Myths & Misconceptions About Negative Reinforcement:

Negative reinforcement is one of the most misunderstood concepts in behavioral psychology. Misconceptions about what it means — and how it works — often lead to its misuse or avoidance altogether. To use reinforcement strategies effectively in education, therapy, parenting, or even the workplace, it’s important to clear up these myths and replace them with accurate, research-based understanding.

- Myth: “Negative” Means Bad or Harmful: One of the most widespread myths is that the word negative automatically implies something bad, harmful, or undesirable. In behavioral psychology, however, negative simply means taking something away. It does not describe the quality or ethical nature of the reinforcement itself. Cooper et al. (2007) explain that negative reinforcement occurs when a behavior is strengthened by removing an aversive condition — like turning off an alarm when you get out of bed. The “negative” part refers to subtraction, not harm.

- Myth: Negative Reinforcement Is the Same as Punishment: Many people mistakenly use these terms interchangeably, but they describe opposite processes. Negative reinforcement increases a desired behavior by removing something unpleasant. Punishment, by contrast, decreases an undesired behavior by adding or applying an unpleasant stimulus. For example, if a child finishes chores to stop nagging, that’s negative reinforcement. If they lose screen time for misbehaving, that’s punishment. They are not the same — and confusing them can lead to poor behavior management (Skinner, 1965).

- Myth: Negative Reinforcement Only Works with Animals: It’s true that negative reinforcement is widely used in animal training, but it’s equally relevant — and common — in human settings. Domjan (2006) points out that negative reinforcement is a core learning process in humans, helping shape everyday behaviors like completing tasks to avoid nagging, leaving early to skip traffic, or wearing a seatbelt to stop the car from beeping. Piazza et al. (1997) also showed how negative reinforcement is used in educational and therapeutic contexts to reduce anxiety, encourage compliance, and manage challenging behaviors.

- Myth: Negative Reinforcement Is Unethical: Some people think that any form of negative reinforcement is inherently wrong or controlling. In reality, whether negative reinforcement is ethical depends on how it’s used. Schwartz and Kusyk (2017) argue that ethics in behavior management depend on the purpose, proportionality, and the impact on the person involved. For example, removing extra assignments when a student consistently meets deadlines is not unethical — it’s a practical motivator that can reduce stress and encourage good study habits.

- Myth: Negative Reinforcement Is More Effective Than Positive Reinforcement: While negative reinforcement can be highly effective in the right situations, research consistently shows that positive reinforcement is often more powerful for creating lasting, positive behavior change. Cameron and Pierce (1994) found that adding rewards like praise, privileges, or incentives not only motivates people but also fosters stronger, more enduring learning and engagement. Relying only on negative reinforcement can lead to avoidance or escape behaviors, while combining both can strike a healthy balance that builds skills and motivation together.

In conclusion, negative reinforcement is not a bad thing — nor is it a quick fix. When applied thoughtfully, it can be an effective tool for shaping behavior by removing an unpleasant stimulus once a desired action is performed. Used well, it can help parents encourage good habits, teachers manage classrooms, therapists guide behavior change, and managers build more productive teams.

However, overdependence on negative reinforcement can have downsides, like promoting avoidance or short-term compliance without addressing root causes. Research shows that blending it with positive reinforcement — adding rewards and recognition — is usually the best approach for encouraging long-term learning and growth (Piazza et al., 1997; Cameron & Pierce, 1994).

By understanding what negative reinforcement really is — and what it isn’t — anyone can apply it more intentionally and ethically. In doing so, we create environments that motivate, support, and inspire people to learn, grow, and thrive while maintaining trust and emotional well-being.

So as you think about your classroom, workplace, or family, ask yourself: How could I use negative reinforcement wisely, balancing it with encouragement, to support growth and build stronger relationships at the same time?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is negative reinforcement in simple terms?

Negative reinforcement is a strategy used to increase a desired behavior by removing something unpleasant when the behavior happens. For example, turning off a loud alarm when you get out of bed encourages you to get up on time in the future.

How is negative reinforcement different from punishment?

Negative reinforcement increases a behavior by taking away an aversive stimulus, while punishment decreases a behavior by adding an unpleasant consequence. They work in opposite ways: negative reinforcement strengthens a behavior; punishment aims to stop it.

Is negative reinforcement bad for people?

No — when used carefully, negative reinforcement is not harmful or unethical. Its ethical use depends on how, why, and where it’s applied. For example, removing extra tasks when an employee meets deadlines is a healthy use of negative reinforcement.

Does negative reinforcement only work with children or animals?

No. Negative reinforcement shapes behavior in people of all ages and in many settings. Adults experience it at work (e.g., fewer meetings for good performance), in daily life (e.g., doing tasks to stop reminders), and even in health behaviors (e.g., taking medicine to stop pain).

Which is more effective: negative or positive reinforcement?

Both can work well, but research shows positive reinforcement often produces stronger, longer-lasting results because it adds motivation through rewards. Many experts recommend combining both approaches to support learning and behavior change.

Can negative reinforcement cause problems?

Yes, if misused. Overusing it can teach people to avoid tasks rather than engage with them. For example, if a student throws tantrums to avoid classwork, removing the task reinforces the tantrum. That’s why it should be applied thoughtfully and often paired with positive reinforcement.

How can I use negative reinforcement responsibly?

Define the behavior you want to increase, make sure the unpleasant stimulus is truly motivating to remove, and only remove it when the desired behavior happens. Monitor results and, whenever possible, pair it with praise or other positive rewards.

References:

- Athens, E. S., & Vollmer, T. R. (2010). An investigation of differential reinforcement of alternative behavior without extinction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43(4), 569–589. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2010.43-569

- Bangash, M., Nayab, T., Zubair, M., Nawaz, H., Ullah, I., & Ullah, S. (2024). Examining the impacts of corporal punishment in secondary schools: Unraveling psychological repercussions on students. Journal of Health and Rehabilitation Research, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.61919/jhrr.v4i2.828

- Bouton, M. E. (2007). Learning and behavior: A contemporary synthesis. Sinauer Associates.

- Bouton, M. E. (2019). Extinction of instrumental (operant) learning: Interference, varieties of context, and mechanisms of contextual control. Psychopharmacology, 236(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-5076-4

- Bouxsein, K., Roane, H., & Harper, T. (2011). Evaluating the separate and combined effects of positive and negative reinforcement on task compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(1), 175–179. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2011.44-175

- Cameron, J., & Pierce, W. D. (1994). Reinforcement, reward, and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 64(3), 363–423. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543064003363

- Chen, X. (2023). A study of using reward and punishment in the education of school-aged children—based on behaviorism theory operant conditioning. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, 10, 86–90. https://doi.org/10.54097/ehss.v10i.6896

- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis.

- Domjan, M. (2006). The principles of learning and behavior. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- Evans, I. M. (2015). Reinforcement, principle of. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 207–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.21051-9

- Hammond, D., Xu, P., Ai, H., & Van Dam, N. (2020). Anxiety and depression related abnormalities in socio-affective learning. Journal of Affective Disorders. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/tg3ec

- Hanley, G. P., Piazza, C. C., Fisher, W. W., & Maglieri, K. A. (2005). On the effectiveness of and preference for punishment and extinction components of function‐based interventions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 38(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2005.6-04

- Huitt, W. (1994). Principles for using behavior modification. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved 03/27/2025, from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/behavior/behmod.html

- Iwata, B. A. (1987). Negative reinforcement in applied behavior analysis: An emerging technology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 20(4), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1987.20-361

- Lalli, J. S., Vollmer, T. R., Progar, P. R., Wright, C., Borrero, J., Daniel, D., Bathold, C. H., Tocco, K, & May, W. (1999). Competition between positive and negative reinforcement in the treatment of escape behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32(3), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1999.32-285

- Leeder, T. M. (2022). Behaviorism, Skinner, and operant conditioning: Considerations for sport coaching practice. Strategies, 35(3), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/08924562.2022.2052776

- Lerman, D. C., & Iwata, B. A. (1996). Developing a technology for the use of operant extinction in clinical settings: An examination of basic and applied research. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29(3), 345–382. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1996.29-345

- Miltenberger, R. G. (2016). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures. Cengage Learning.

- Mowrer, O. H. (1951). Two-factor learning theory: Summary and comment. Psychological Review, 58(5), 350–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0058956

- Piazza, C. C., Fisher, W. W., Hanley, G. P., Remick, M. L., Contrucci, S. A., & Aitken, T. L. (1997). The use of positive and negative reinforcement in the treatment of escape‐maintained destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30(2), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1997.30-279

- Piazza, C. C., Moes, D. R., & Fisher, W. W. (1996). Differential reinforcement of alternative behavior and demand fading in the treatment of escape‐maintained destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29(4), 569–572. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1996.29-569

- Reed, F. D. D., & Lovett, B. J. (2007). Views on the efficacy and ethics of punishment: Results from a national survey. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 4(1), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100832

- Schultz, W. (2016). Dopamine reward prediction error coding. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 18(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.1/wschultz

- Schwartz, M., & Kusyk, S. M. (2017). Ethical decision-making theory: Revisiting the moral intensity construct. Academy of Management, 2017(1), 16266. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2017.16266abstract,

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. BF Skinner Foundation.

- Skinner, B. F. (1965). Science and human behavior. Simon and Schuster.

- Wergård, E., Temrin, H., Forkman, B., Spångberg, M., Fredlund, H., & Westlund, K. (2015). Training pair-housed Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) using a combination of negative and positive reinforcement. Behavioural Processes, 113, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2014.12.008

- Whitman, M. A. (1974). Behavior modification: Introduction and implications. De Paul Law Review, 24(4), 949–959. Retrieved From: https://via.library.depaul.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2732&context=law-review

- Xu, S., Sun, Y., Huang, M., Huang, Y., Han, J., Tang, X., & Ren, W. (2021). Emotional state and feedback-related negativity induced by positive, negative, and combined reinforcement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 647263. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647263

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College