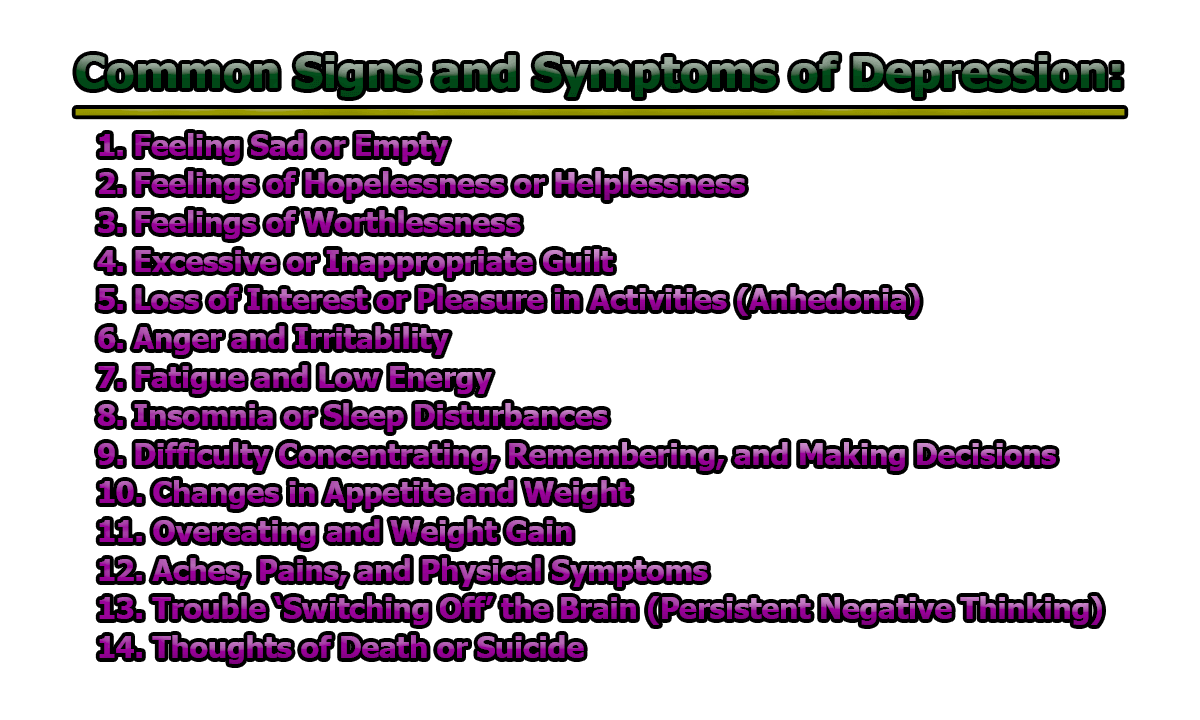

Common Signs and Symptoms of Depression:

Depression, clinically known as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), is a pervasive mental health condition affecting approximately 280 million individuals worldwide (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023). The symptoms of depression extend far beyond persistent sadness; they encompass emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and physical dimensions, varying significantly among individuals. To be diagnosed with depression, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) stipulates that symptoms must persist for at least two weeks and impair daily functioning (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). In the rest of this article, we will explore some of the common signs and symptoms of depression and how to overcome them.

1. Feeling Sad or Empty: One of the most universally recognized symptoms of depression is a pervasive and persistent feeling of sadness. Individuals may describe this state as a heavy emotional burden or an overwhelming sense of emptiness. This mood is typically present most of the day, nearly every day, and is not necessarily triggered by specific events (APA, 2013). Some people may express that they feel “numb” or unable to experience happiness or joy, even in situations that previously brought pleasure. This symptom, often referred to as a “low mood,” can be accompanied by crying spells or a blank emotional state.

Research Insight: According to the National Institute of Mental Health (2024), sadness in depression is not just a temporary emotional reaction to life circumstances but rather a sustained emotional state that interferes with daily life. It may also be misinterpreted by others as laziness or disinterest, which can increase the affected individual’s sense of isolation.

2. Feelings of Hopelessness or Helplessness: Depression often clouds an individual’s outlook on life, making them feel that their situation is hopeless and unchangeable. Hopelessness is characterized by negative expectations for the future and the belief that positive change is impossible. Helplessness, on the other hand, reflects the feeling that no one—not even oneself—can help resolve the current state of despair (Beck et al., 1979). These cognitive distortions contribute to a self-reinforcing cycle of negative thinking and withdrawal from life activities.

Research Insight: Studies show that hopelessness is a strong predictor of suicidal ideation and behaviors, especially when it is accompanied by the belief that no actions or interventions will make a difference (Joiner, 2005).

3. Feelings of Worthlessness: People with depression often experience extreme self-criticism and feelings of worthlessness. They may believe that they have no value, that they are a burden to others, or that their lives lack purpose or meaning. This symptom can manifest as excessive self-blame over minor mistakes or perceived flaws, sometimes even regarding events from the distant past (APA, 2013).

Research Insight: Pizzagalli (2014) notes that low self-worth and self-directed negative emotions are not just psychological phenomena but may be linked to changes in brain regions associated with reward and self-evaluation, such as the anterior cingulate cortex.

4. Excessive or Inappropriate Guilt: Guilt is a normal emotion, but in depression, it often becomes distorted and exaggerated. Individuals may ruminate over past mistakes or believe they are responsible for things beyond their control. Unlike healthy guilt, which can motivate corrective behavior, depressive guilt is persistent and paralyzing. This can cause the individual to internalize blame for events or relationships that have little to do with their actions (Pizzagalli, 2014).

Research Insight: The presence of excessive guilt has been particularly noted in individuals with melancholic depression, where it serves as a diagnostic marker (APA, 2013). Persistent guilt may also impair interpersonal relationships, as the individual may withdraw or over-apologize in social contexts.

5. Loss of Interest or Pleasure in Activities (Anhedonia): Anhedonia is one of the core symptoms of major depressive disorder and refers to a diminished ability to experience pleasure or interest in previously enjoyable activities. This may include hobbies, social interaction, exercise, music, or sexual activity. The individual may stop participating in these activities altogether or find them unfulfilling and dull when they do (Treadway & Zald, 2011).

Research Insight: Anhedonia is not only emotionally distressing but also biologically rooted. It has been linked to dysfunction in the brain’s reward circuitry, particularly in areas like the ventral striatum. This symptom is a strong predictor of poor treatment outcomes and may require specialized therapeutic approaches (Treadway & Zald, 2011).

6. Anger and Irritability: Depression is commonly associated with sadness, but for many individuals—especially men, adolescents, and children—irritability, anger, or agitation may be more prominent symptoms. A person with depression may become easily frustrated, lose their temper over minor issues, or feel generally “on edge” (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2024). This emotional volatility may be due to the inner turmoil and psychological exhaustion that often accompany depression.

Research Insight: According to Fava et al. (2010), irritability is present in up to 50% of individuals diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). It may reflect an underlying sense of helplessness and internalized frustration, manifesting externally as hostility toward others.

7. Fatigue and Low Energy: One of the most commonly reported symptoms of depression is persistent fatigue—a state of chronic exhaustion that affects physical and mental energy levels. This is not simply tiredness that improves with rest; instead, people with depression may feel drained regardless of how much they sleep (APA, 2013).

This fatigue often interferes with daily functioning. Tasks that once seemed easy—such as getting out of bed, cooking, or commuting—may feel overwhelming. This contributes to further withdrawal from social, occupational, and personal responsibilities.

Research Insight: According to Höhn et al. (2013), fatigue in depression may be related to inflammatory processes in the body, as well as disruptions in circadian rhythm and neurotransmitter imbalances.

8. Insomnia or Sleep Disturbances: Sleep problems are deeply intertwined with depression. Many people with depression experience insomnia, including difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking too early and being unable to go back to sleep. On the other hand, some individuals may oversleep or struggle to get out of bed (hypersomnia) (NIMH, 2024).

Sleep disturbances both exacerbate and are exacerbated by depressive symptoms, leading to a vicious cycle of poor sleep and worsening mood.

Research Insight: According to Baglioni et al. (2011), insomnia is not only a symptom but also a risk factor for the onset and recurrence of depression. Effective treatment often involves addressing both mood and sleep disturbances concurrently.

9. Difficulty Concentrating, Remembering, and Making Decisions: Depression often impairs cognitive functioning, making it hard to concentrate, stay focused, or make even simple decisions. Individuals may describe feeling mentally “foggy” or distracted and may struggle to recall information or complete tasks that once felt routine (Rock et al., 2014).

These difficulties can negatively impact academic, work, and personal life, sometimes leading to further frustration and guilt, which worsen depressive symptoms.

Research Insight: Cognitive impairment in depression has been linked to changes in the function of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus—areas of the brain responsible for executive function and memory (McIntyre et al., 2013).

10. Changes in Appetite and Weight: Depression can lead to significant changes in appetite—either a marked decrease or increase. Some individuals may lose interest in food altogether and experience weight loss, while others may turn to food for comfort, resulting in weight gain (APA, 2013).

These changes are not always deliberate and may reflect broader disturbances in reward processing and self-regulation associated with depression.

Research Insight: A study by Lutter and Nestler (2009) suggests that appetite changes in depression are associated with altered signaling in the hypothalamus and dopamine pathways, impacting both hunger cues and the pleasure derived from eating.

11. Overeating and Weight Gain: In contrast to appetite loss, some individuals with depression may experience increased appetite and significant weight gain. This behavior is often associated with emotional eating, in which food is used as a coping mechanism for emotional distress, boredom, or loneliness (APA, 2013). Carbohydrate-rich comfort foods, in particular, may temporarily boost serotonin levels, which can create a short-lived feeling of well-being but ultimately worsen depressive symptoms.

Research Insight: According to Lutter and Nestler (2009), depression-related overeating is associated with reward-system dysfunction, particularly involving dopamine and leptin signaling. This can make the brain less responsive to natural rewards, leading individuals to seek more food to achieve emotional satisfaction.

Moreover, atypical depression, a subtype of major depressive disorder, specifically includes symptoms such as increased appetite and hypersomnia (Thase, 2007).

12. Aches, Pains, and Physical Symptoms: Depression does not only affect emotional well-being—it can also cause unexplained physical symptoms, such as chronic pain, headaches, backaches, or digestive problems. These symptoms are often resistant to medical treatment and may not have a clear physical cause (NIMH, 2024). This mind-body connection can lead individuals to seek help from general practitioners for physical discomfort before receiving a mental health diagnosis.

Research Insight: According to Bair et al. (2003), nearly two-thirds of individuals with depression report somatic symptoms. These physical manifestations may result from increased inflammation and dysregulation of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and norepinephrine, which are involved in both mood and pain perception.

13. Trouble ‘Switching Off’ the Brain (Persistent Negative Thinking): People with depression often experience rumination, a cognitive process characterized by repetitive, intrusive, and negative thoughts. This persistent mental activity makes it difficult for individuals to relax, sleep, or focus on tasks. They may dwell on past mistakes, worries about the future, or feelings of self-doubt and failure (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000).

Research Insight: Rumination not only maintains depressive symptoms but also predicts their severity and duration. It is closely associated with dysfunction in the default mode network of the brain, which is active during rest and self-referential thought (Hamilton et al., 2011).

14. Thoughts of Death or Suicide: Perhaps the most serious symptom of depression is the presence of suicidal ideation—recurrent thoughts about death, dying, or taking one’s own life. These thoughts can range from passive (e.g., “I wish I wouldn’t wake up tomorrow”) to active planning of suicide. Not all individuals with depression have suicidal thoughts, but those who do require immediate professional intervention (APA, 2013).

Research Insight: Suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide, and depression is a major contributing factor. The World Health Organization (2025) estimates that over 720 000 people die by suicide every year. According to Joiner (2005), suicidal ideation is driven by a combination of perceived burdensomeness, a sense of hopelessness, and social disconnection.

Warning signs can include verbal expressions of despair, withdrawal from loved ones, giving away possessions, and sudden mood improvement after a period of deep depression—potentially signaling a decision to act.

Diagnosis and When to Seek Help:

Diagnosing depression involves a comprehensive clinical evaluation that considers a person’s psychological, emotional, and physical symptoms. Mental health professionals often conduct structured clinical interviews and use standardized screening tools, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which assesses the severity and frequency of depressive symptoms over the past two weeks (Kroenke et al., 2001).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) provides the standard criteria for diagnosing major depressive disorder. According to the American Psychiatric Association (2013), a diagnosis requires that an individual experiences five or more of the core symptoms, such as depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, changes in weight or appetite, fatigue, sleep disturbances, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, and suicidal ideation. These symptoms must persist most of the day, nearly every day, for at least two consecutive weeks and cause significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

It is crucial that individuals seek professional help when symptoms interfere with daily life, relationships, or work performance. Early intervention can lead to better outcomes and may prevent the condition from worsening. Those experiencing thoughts of self-harm or suicide should seek immediate medical attention or contact emergency services, as this is considered a psychiatric emergency (NIMH, 2024).

Treatment Options:

A. Psychotherapy and Medication: Evidence supports the effectiveness of a combination of psychotherapy and medication for treating moderate to severe depression. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), one of the most widely studied and applied forms of therapy, focuses on identifying and challenging negative thought patterns and behaviors. CBT has demonstrated high efficacy in reducing symptoms of depression and preventing relapse (Butler et al., 2006).

Pharmacological treatments include antidepressants, particularly Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine, sertraline, and citalopram. These medications work by increasing serotonin levels in the brain, thereby enhancing mood and emotional regulation (Mayo Clinic, 2022). However, antidepressants usually take 4 to 8 weeks to show noticeable improvements, and some individuals may need to try several medications before finding the most effective one with manageable side effects.

For individuals with treatment-resistant depression, options such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) may be considered (APA, 2013).

B. Lifestyle Interventions: In addition to clinical treatment, lifestyle modifications can play a significant role in alleviating depressive symptoms and enhancing overall well-being:

- Regular Physical Activity: Exercise has been shown to increase the availability of neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, which are crucial for mood regulation. Even moderate activity, such as walking for 30 minutes a day, can reduce symptoms of depression (Blumenthal et al., 1999).

- Balanced Nutrition: Diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids, whole grains, fruits, and vegetables are linked to improved mental health. A deficiency in nutrients such as folate, vitamin D, or B12 has been associated with increased risk of depression (Sánchez-Villegas et al., 2007).

- Mindfulness and Stress Management: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and other relaxation techniques like yoga and deep breathing exercises can help individuals manage stress and reduce ruminative thinking (Hofmann et al., 2010).

- Social Engagement: Maintaining connections with supportive people can reduce feelings of isolation and help foster a sense of belonging and purpose. Participating in social activities or support groups can be beneficial.

- Avoiding Alcohol and Substance Abuse: Substances like alcohol and drugs can worsen depressive symptoms, interfere with medications, and increase the risk of suicidal behavior (Harvard Health Publishing, 2024).

Supporting Someone with Depression:

Support from friends and family can have a profound impact on the recovery journey of someone with depression. Compassionate and nonjudgmental support helps reduce stigma, which is often a barrier to seeking help. Ways to provide support include:

- Encouraging professional help: Gently suggest that the person speak with a mental health professional. Offer to help them research options, schedule appointments, or accompany them to visits.

- Being present and listening: Simply being there, offering a listening ear, and validating their experiences can help the person feel seen and understood. Avoid offering unsolicited advice or minimizing their feelings.

- Maintaining communication: Stay in regular contact. Even a simple message or call can let someone know they are not alone.

- Encouraging healthy routines: While it’s important not to pressure the person, gently encouraging participation in daily activities such as going for a walk, eating meals, or spending time outside can be helpful.

- Reducing stressors: Where possible, assist with practical tasks such as errands, chores, or childcare to help reduce the burden of daily responsibilities (NIMH, 2024).

If the person expresses suicidal thoughts or intent, do not leave them alone and seek emergency support immediately by calling emergency services or a suicide prevention hotline.

At the end of the day, we can say that Depression is a common yet serious mental health condition that affects millions of individuals globally. It can present with a wide array of emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and physical symptoms, including persistent sadness, fatigue, loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities, irritability, appetite or sleep disturbances, and, in severe cases, suicidal ideation. These symptoms vary from person to person and can significantly impair daily functioning and overall well-being.

Despite its challenges, depression is highly treatable. A combination of professional interventions—such as psychotherapy, medication, and lifestyle modifications—has been proven effective in alleviating symptoms and preventing relapse. Early detection and treatment are vital, not only for symptom relief but also for improving long-term outcomes.

Anyone who suspects that they—or someone they care about—may be experiencing symptoms of depression is strongly encouraged to seek medical advice promptly. Consulting a doctor or mental health professional can initiate access to the appropriate support, diagnosis, and treatment. With timely and appropriate care, individuals living with depression can experience substantial improvements in quality of life, emotional health, and personal relationships. In some cases, seeking help can even be life-saving.

References:

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Baglioni, C., Battagliese, G., Feige, B., Spiegelhalder, K., Nissen, C., Voderholzer, U., … & Riemann, D. (2011). Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1-3), 10-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011

- Bair, M. J., Robinson, R. L., Katon, W., & Kroenke, K. (2003). Depression and pain comorbidity: A literature review. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(20), 2433-2445. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press.

- Blumenthal, J. A., Babyak, M. A., Moore, K. A., Craighead, W. E., Herman, S., Khatri, P., … & Krishnan, K. R. (1999). Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Archives of Internal Medicine, 159(19), 2349–2356. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.159.19.2349

- Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003

- Fava, M., Hwang, I., Rush, A. J., Sampson, N., Walters, E. E., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). The importance of irritability as a symptom of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry, 15(8), 856–867. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2009.20

- Hamilton, J. P., Furman, D. J., Chang, C., Thomason, M. E., Dennis, E., & Gotlib, I. H. (2011). Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: Implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biological Psychiatry, 70(4), 327–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.003

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2024). Understanding depression. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/understanding-depression

- Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018555

- Höhn, P., Menne-Lothmann, C., Peeters, F., Nicolson, N. A., Jacobs, N., Derom, C., Thiery, E., van Os, J., & Wichers, M. (2013). Moment-to-moment transfer of positive emotions in daily life predicts future course of depression in both general population and patient samples. PLoS ONE, 8(9), e75655. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075655

- Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press.

- Konttinen, H., Mannisto, S., Sarlio-Lahteenkorva, S., Silventoinen, K., & Haukkala, A. (2010). Emotional eating, depressive symptoms and self-reported food consumption. A population-based study. Appetite, 54(3), 473-479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2010.01.014

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Lutter, M., & Nestler, E. J. (2009). Homeostatic and hedonic signals interact in the regulation of food intake. Journal of Nutrition, 139(3), 629–632. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.108.097618

- Mayo Clinic. (2022). Depression (major depressive disorder). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression

- McIntyre, R. S., Cha, D. S., Soczynska, J. K., Woldeyohannes, H. O., Gallaugher, L. A., Kudlow, P., … & Baskaran, A. (2013). Cognitive deficits and functional outcomes in major depressive disorder: Determinants, substrates, and treatment interventions. Depression and Anxiety, 30(6), 515–527. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22063

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504

- Pizzagalli, D. A. (2014). Depression, stress, and anhedonia: Toward a synthesis and integrated model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 393-423. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185606

- Rock, P. L., Roiser, J. P., Riedel, W. J., & Blackwell, A. D. (2014). Cognitive impairment in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 44(10), 2029-2040. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002535

- Sanchez-Villegas, A., Henríquez, P., Figueiras, A., Ortuño, F., Lahortiga, F., & Martínez-González, M. A. (2007). Long chain omega-3 fatty acids intake, fish consumption and mental disorders in the SUN cohort study. European Journal of Nutrition, 46(6), 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-007-0671-x

- Thase, M. E. (2007). Recognition and diagnosis of atypical depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68(Suppl 8), 11–16.

- Treadway, M. T., & Zald, D. H. (2011). Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: Lessons from translational neuroscience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(3), 537–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.06.006

- Wessely, S. (2001). Chronic fatigue: Symptom and syndrome. Annals of Internal Medicine, 134(9 Pt 2), 838–843. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-134-9_part_2-200105011-00007

- World Health Organization. (2023). Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- World Health Organization. (2025). Suicide. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College