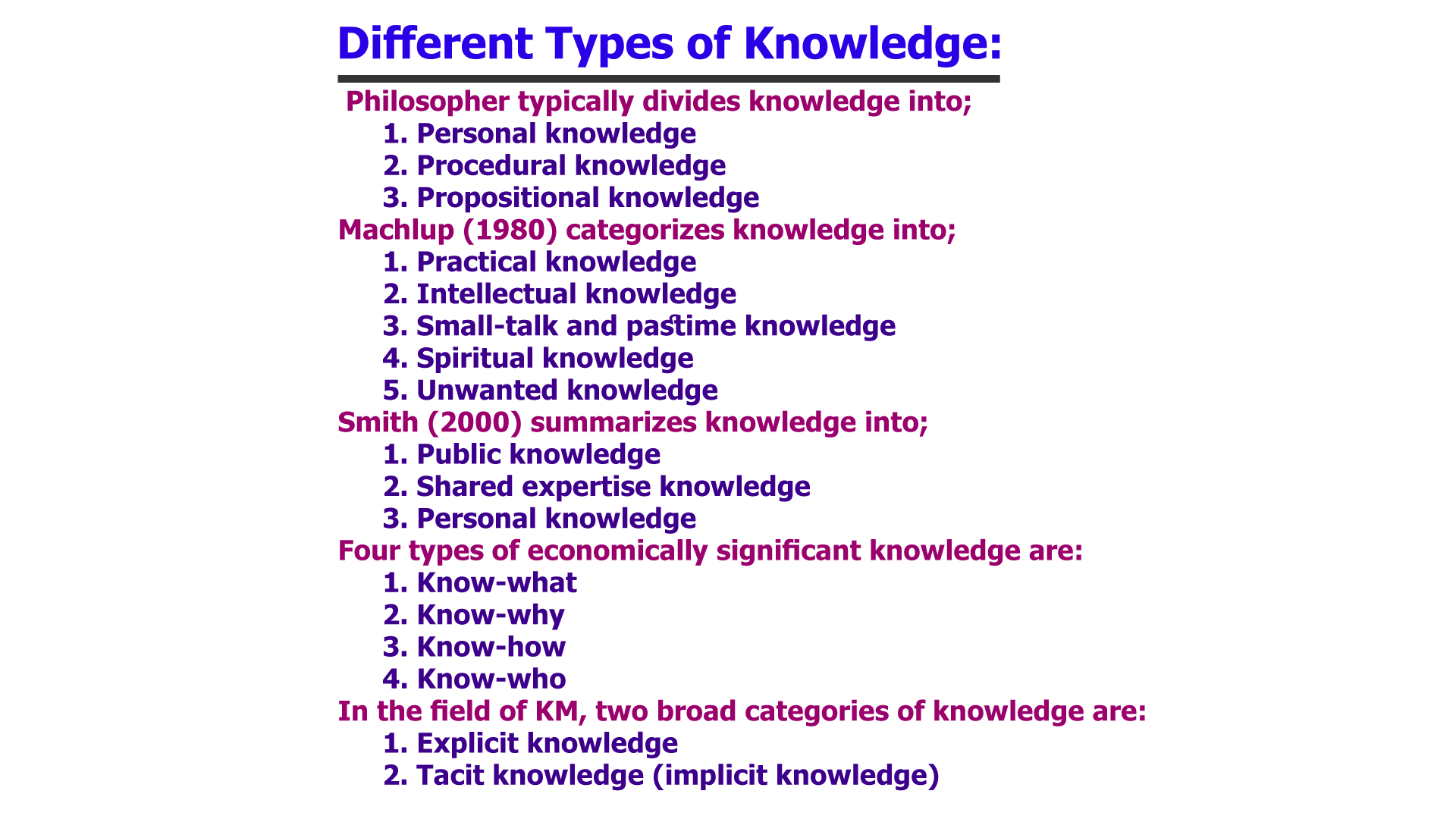

Different Types of Knowledge:

Knowledge is a broad and complex concept that can be approached from various perspectives. It is a vital part of human development and progress, and it plays a critical role in shaping our perceptions of the world around us. In this article, we will explore the different types of knowledge.

Philosopher typically divides knowledge into three categories:

1. Personal knowledge: Personal knowledge is knowledge that is based on personal experiences, beliefs, and values. It is the type of knowledge that is often subjective and difficult to quantify. Personal knowledge is acquired through personal experiences and interactions with the world around us. This type of knowledge is often closely tied to our emotions, and it can be influenced by our cultural and social backgrounds.

Personal knowledge is important because it helps us understand our own perspectives and biases. It can also help us relate to others and appreciate their unique perspectives. For example, someone who has personal knowledge of growing up in a particular cultural or social environment may be better able to understand and relate to others who have had similar experiences.

2. Procedural knowledge: Procedural knowledge refers to the knowledge of how to perform a particular task or skill. It is the type of knowledge that is often associated with practical skills, such as driving a car or playing a musical instrument. Procedural knowledge is acquired through practice and repetition, and it is often closely tied to muscle memory.

Procedural knowledge is important because it allows us to perform tasks and skills with greater efficiency and accuracy. It can also help us develop expertise in a particular field or area of study. For example, a surgeon must have a high degree of procedural knowledge in order to perform complex surgeries with precision and skill.

3. Propositional knowledge: Propositional knowledge, also known as declarative knowledge, refers to knowledge that is based on facts and propositions. It is the type of knowledge that is often associated with academic disciplines, such as mathematics, science, and philosophy. Propositional knowledge is acquired through education and formal instruction, and it is often expressed in language.

Propositional knowledge is important because it allows us to understand and explain the world around us. It can also help us make informed decisions and solve problems. For example, a scientist must have a high degree of propositional knowledge in order to develop new theories and conduct experiments to test them.

Machlup (1980) categorizes knowledge into five types:

- Practical knowledge: Practical knowledge, which is useful in an individual’s work, decisions and actions. Besides, professional knowledge, business knowledge, and political knowledge, etc. are regarded as practical knowledge.

- Intellectual knowledge: Intellectual knowledge, which satisfies intellectual curiosity.

- Small-talk and pastime knowledge: Small-talk and pastime knowledge, which satisfies non-intellectual curiosity or the desire for light entertainment.

- Spiritual knowledge: Spiritual knowledge, which relates to religion and mystical experiences.

- Unwanted knowledge: Unwanted knowledge, which is an outsight of one’s interests knowledge and is usually accidentally acquired.

Smith (2000) summarizes knowledge into three types:

- Public knowledge, which is explicit, taught and shared routinely.

- Shared expertise knowledge, which is shared by knowledge workers in their work.

- Personal knowledge, which exists tacitly in people’s mind. It is knowledge by acquaintance.

Four types of economically significant knowledge are:

- Know-what: Know-what refers to knowledge about facts. Here, knowledge is close to what is normally called information.

- Know-why: Know-why refers to scientific knowledge of the principles and laws of nature.

- Know-how: Know-how refers to skills or the capability to do something.

- Know-who: Know-who involves information about who knows what and who knows how to do what.

In the field of KM, two broad categories of knowledge are:

- Explicit knowledge: Explicit knowledge can be easily expressed, articulated, or encoded (codified), gathered, organized, transferred, or shared with others through social interaction. Examples of such knowledge are trade secrets, standards, patents, manuals, online databases, drawings, photographs, etc.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) defined explicit knowledge that can be expressed in words and numbers and can be easily communicated and shared in the form of hard data, scientific formulae, codified procedures, or universal principles.

According to Polany (1966) – Explicit knowledge or ‘codified’ knowledge, refers to knowledge that is transmittable in some systemic language — such as words, numbers, diagrams or models. As such, it is easily transmitted orally and in written or electronic form. It can also easily be manipulated and stored in various databases and repositories.

Explicit knowledge is knowledge that has been explained, recorded, or documented. Explicit knowledge is packaged, easily codified, transferable and communicable. Explicit knowledge, being available in the public domain, has also been called public knowledge or information.

- Tacit knowledge (implicit knowledge): Tacit knowledge is personal, embedded in the minds of people. It is intuitive, contextual, linked to experience and memories, and is difficult to formalize, document, and communicate. Such knowledge is difficult to identify, quantify and convert into real value unless a structured approach is not adopted to manage such knowledge. It is something that we do possess unconsciously and most of the time we are not aware of its existence. Such knowledge is self-acquired through experience, reading, learning, training, and interaction. It is different from the knowledge available in written records, as it is hidden in minds and processes in the form of expertise, skills, and competencies, normally gained through experience, socialization, and interaction with the environment. An example of tacit knowledge at work would be the reference librarian who on the basis of his/her experience can tell from where to find the best explanation of “conservation and preservation” or “lexicography”.

Polanyi (1966) defines tacit knowledge as personal, context-specific, and, thus, not easily visible and expressible — nor easy to formalize and communicate to others. Individuals may know more than they are able to articulate. Tacit knowledge is based on subjective insights, intuitions, and hunches and is deeply rooted in an individual’s actions and experiences and ideals, values, and emotions.

Tacit knowledge, sometimes known as implicit knowledge, is unspoken and hidden. It is the expertise and assumptions that individuals develop over the years that may never have been recorded or documented.

Tacit knowledge is very important in the organizational context, where it is embedded in the systems, processes, tools, and techniques that people create by utilizing their experience gained over a long period of time. In the corporate sector, it has to be gathered and preserved for furthering the organization’s objectives, otherwise, a great deal of such knowledge is lost when people leave the organization in search of better job opportunities due to a lack of “on the job” incentives.

References:

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press.

- Polanyi, M. (1958). Personal knowledge: Towards a post-critical philosophy. University of Chicago Press.

- Anderson, J. R. (1983). The architecture of cognition. Harvard University Press.

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

- Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn?. Educational psychology review, 16(3), 235-266.

- Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem-solving. Prentice-Hall.

- Resnick, L. B. (1987). Education and learning to think. National Academy Press.

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. National Academy Press.

- Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In Knowing, Learning, and Instruction: Essays in Honor of Robert Glaser (pp. 453-494). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Pollock, J. E., & Chandler, R. W. (2003). Cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience: Integration and implications for learning and instruction. In Advances in psychology research (Vol. 20, pp. 13-38). Nova Science Publishers.

- Resnick, M. (1991). Shared cognition: Thinking as social practice. In Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 1-20). American Psychological Association.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- DiPaola, M. F., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2003). The knowledge gap: An exploratory study of the relationship between explicit knowledge, implicit knowledge, and behavior. Journal of Educational Administration, 41(5), 436-454.

- Sternberg, R. J. (1985). Beyond IQ: A triarchic theory of human intelligence. Cambridge University Press.

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

- Perkins, D. N. (1992). Smart schools: Better thinking and learning for every child. Free Press.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Clancey, W. J. (1997). Situated cognition: On human knowledge and computer representations. Cambridge University Press.

- Rogoff, B. (1995). Observing sociocultural activity on three planes: participatory appropriation, guided participation, and apprenticeship. In J. V. Wertsch, P. del Río, & A. Alvarez (Eds.), Sociocultural studies of mind (pp. 139-164). Cambridge University Press.

Assistant Teacher at Zinzira Pir Mohammad Pilot School and College