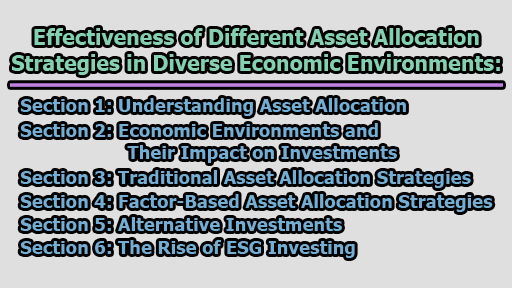

Effectiveness of Different Asset Allocation Strategies in Diverse Economic Environments:

In the ever-changing landscape of global economies, investors face the challenging task of managing their portfolios to navigate through various economic environments. The effectiveness of asset allocation strategies becomes paramount in determining investment success. In this article, we will explore the effectiveness of different asset allocation strategies in diverse economic environments.

Section 1: Understanding Asset Allocation:

Asset allocation serves as the cornerstone of effective portfolio management, providing investors with a structured approach to balance risk and return. Before delving into specific strategies, it is imperative to comprehend the fundamental concept of asset allocation.

1.1 Diversification as a Risk Management Tool: Diversification, a key principle of asset allocation, involves spreading investments across different asset classes to minimize the impact of poor performance in any single investment on the overall portfolio. The rationale behind diversification is rooted in the fact that different assets have varying risk and return profiles, and they may respond differently to economic events.

- Equities: Historically, stocks have exhibited higher volatility but also the potential for substantial returns, especially during bullish market conditions. The inclusion of equities in a portfolio can enhance its growth potential.

- Bonds: Bonds, on the other hand, are generally considered more stable and act as a source of income through interest payments. They often serve as a counterbalance to the volatility of stocks.

- Cash Equivalents: Cash equivalents, such as money market funds, provide liquidity and stability. While offering lower returns compared to stocks and bonds, they act as a cushion during turbulent market conditions.

Diversification is not just about selecting different asset classes; it also involves considering factors such as geographic regions, industries, and market capitalizations. By spreading investments across a variety of assets, investors aim to reduce the overall risk of the portfolio.

1.2 Aligning with Investment Objectives and Risk Tolerance: The asset allocation decision should be aligned with an investor’s financial goals, time horizon, and risk tolerance. For instance, a young investor with a long time horizon may opt for a more aggressive allocation, with a higher proportion allocated to equities, as they can tolerate short-term market fluctuations in pursuit of long-term capital appreciation.

- Risk Tolerance: Understanding one’s risk tolerance is crucial. Risk-averse investors may prefer a more conservative allocation with a higher allocation to bonds and cash equivalents, prioritizing capital preservation over aggressive growth.

- Investment Horizon: The investment horizon, whether short-term or long-term, influences the choice of assets. Longer investment horizons may allow for a higher exposure to equities, while shorter horizons may necessitate a more conservative approach.

Asset allocation, therefore, is not a one-size-fits-all strategy; it is a personalized decision that reflects an investor’s unique financial circumstances and preferences.

1.3 Periodic Rebalancing for Maintaining Optimal Allocation: Market fluctuations can cause deviations from the initially chosen asset allocation. Periodic rebalancing involves adjusting the portfolio to bring it back to its target allocation. This disciplined approach ensures that the portfolio stays in line with the investor’s risk tolerance and investment objectives.

- Sell High, Buy Low: Rebalancing inherently involves selling assets that have performed well and buying those that may have underperformed. This contrarian approach helps investors capitalize on market inefficiencies and maintain the desired risk-return profile.

- Adapting to Market Conditions: Economic environments are dynamic, and what may have been an optimal allocation in one market condition may no longer hold true in another. Rebalancing allows investors to adapt to changing market dynamics and avoid unintended overexposure to specific asset classes.

Understanding the significance of diversification, aligning asset allocation with individual goals and risk tolerance, and implementing disciplined rebalancing are foundational principles that set the stage for exploring the intricacies of specific asset allocation strategies across diverse economic environments.

Section 2: Economic Environments and Their Impact on Investments:

Understanding the dynamics of different economic environments is essential for investors seeking to tailor their asset allocation strategies to prevailing market conditions. Economic cycles, characterized by periods of expansion, contraction, and recovery, influence the performance of various asset classes. Examining how investments respond to different economic environments is crucial for constructing a resilient and adaptive portfolio.

2.1 Bull Markets:

2.1.1 Characteristics of Bull Markets: Bull markets are characterized by a sustained rise in economic activity, increasing employment, and optimistic investor sentiment. During these periods, consumer spending tends to be robust, corporate profits often rise, and stock markets generally experience upward trends.

- Favorable Conditions for Equities: In bull markets, equities are often the star performers, as the positive economic backdrop contributes to increased corporate earnings and higher stock prices.

- Challenges of Timing: Identifying the onset of a bull market is challenging, as market timing is inherently uncertain. Investors who are overly cautious might miss out on potential gains, while those who enter too late may face increased risks.

2.1.2 Asset Allocation Strategies for Bull Markets:

- Equity Emphasis: Given the historical outperformance of stocks during bull markets, investors may consider a more aggressive asset allocation with a higher proportion allocated to equities. Growth-oriented sectors and riskier assets may also be favored.

- Cautionary Measures: Despite the positive outlook, prudent investors should avoid excessive risk-taking and ensure that their portfolios remain diversified. Over-concentration in a single asset class, even in a bull market, can expose investors to potential losses if market conditions suddenly change.

- Regular Monitoring: Bull markets are not indefinite, and periodic reassessment of the investment strategy is crucial. Regular monitoring allows investors to identify signs of potential shifts in market sentiment and adjust their asset allocation accordingly.

2.2 Bear Markets:

1.2.1 Characteristics of Bear Markets: Bear markets are characterized by declining economic activity, rising unemployment, and a general pessimism among investors. During these downturns, stock prices often experience significant declines, and risk-averse behavior becomes prevalent.

- Safe-Haven Assets: Investors often flock to safe-haven assets such as government bonds and gold during bear markets. These assets provide stability and act as a hedge against the heightened volatility in equities.

- Impact on Equities: Equities, especially those deemed riskier, can face substantial losses during bear markets. Defensive sectors such as utilities and consumer staples may outperform, given their perceived stability.

2.2.2 Asset Allocation Strategies for Bear Markets:

- Defensive Posture: A defensive asset allocation strategy involves reducing exposure to equities and increasing allocations to safer assets like bonds and cash equivalents. This approach aims to protect capital during market downturns.

- Diversification for Stability: Diversification becomes even more critical during bear markets as correlations between asset classes can shift. A well-diversified portfolio with exposure to uncorrelated assets can help mitigate losses.

- Selective Equity Investments: While equities as a whole may face challenges in bear markets, certain defensive stocks or sectors may exhibit resilience. Utilities, healthcare, and consumer staples are examples of sectors that may perform relatively well.

2.3 Economic Recessions:

2.3.1 Unique Challenges of Economic Recessions: Economic recessions present unique challenges as they are often accompanied by a contraction in economic output, increased unemployment, and reduced consumer spending. Traditional correlations between asset classes may break down, and unexpected events can lead to heightened market volatility.

- Uncertainty and Market Volatility: The heightened uncertainty during economic recessions can lead to increased market volatility. Investors may face challenges in predicting market movements, making adaptive asset allocation strategies crucial.

- Fixed-Income Opportunities: Government bonds, particularly those with high credit quality, may be sought after as investors prioritize capital preservation. Central bank policies, such as interest rate cuts, can influence the performance of fixed-income securities.

2.3.2 Asset Allocation Strategies for Economic Recessions:

- Quality Fixed-Income Investments: Investors may increase their exposure to high-quality bonds and other fixed-income securities, which are perceived as safer during economic downturns. Government bonds, investment-grade corporate bonds, and Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) are examples.

- Defensive Equities: Defensive stocks, characterized by stable earnings and dividends, may outperform during economic recessions. These stocks are often found in sectors like healthcare, consumer staples, and utilities.

- Tactical Adjustments: Economic recessions require a tactical approach to asset allocation, with a focus on adaptability. Periodic reassessment of the economic landscape allows investors to make timely adjustments to their portfolios.

Understanding the impact of different economic environments on investments provides the foundation for selecting and implementing effective asset allocation strategies.

Section 3: Traditional Asset Allocation Strategies:

Traditional asset allocation strategies provide a systematic framework for investors to construct and manage their portfolios. These strategies, which include strategic, tactical, and dynamic asset allocation, aim to balance risk and return based on an investor’s financial goals and risk tolerance.

3.1 Strategic Asset Allocation:

3.1.1 Long-Term Portfolio Construction:

- Objective Setting: Strategic asset allocation begins with setting clear investment objectives, considering factors such as an investor’s risk tolerance, time horizon, and financial goals. This long-term perspective helps determine the initial allocation to different asset classes.

- Diversification as Core Principle: The strategy relies on the principle of diversification, spreading investments across various asset classes to reduce risk. The initial asset allocation is determined by the investor’s risk profile, with a typical mix of stocks, bonds, and cash equivalents.

3.1.2 Rebalancing for Portfolio Maintenance:

- Periodic Reassessment: While the initial asset allocation is based on long-term goals, periodic reassessment is crucial. Changes in market conditions, economic outlook, or personal circumstances may necessitate adjustments to the portfolio.

- Buy-and-Hold Approach: Strategic asset allocation often adopts a buy-and-hold approach, where investors maintain their chosen allocation through market ups and downs. Rebalancing involves selling assets that have outperformed and buying those that have underperformed to bring the portfolio back to its target allocation.

3.2 Tactical Asset Allocation:

3.2.1 Short-Term Adjustments Based on Market Conditions:

- Market Timing Challenges: Tactical asset allocation involves making short-term adjustments to a portfolio’s allocation based on current market conditions. However, accurately timing the market is challenging, and mistimed decisions can lead to suboptimal outcomes.

- Data and Analysis: Tactical asset allocators often rely on market indicators, economic data, and technical analysis to make short-term adjustments. The goal is to capitalize on perceived opportunities or mitigate risks as market conditions evolve.

3.2.2 Flexibility and Risk Management:

- Adapting to Changing Environments: The flexibility of tactical asset allocation allows for responsive adjustments in the face of changing market dynamics. This adaptability is particularly valuable during periods of economic uncertainty or market volatility.

- Risk Mitigation: Tactical asset allocation aims to mitigate risks by adjusting the portfolio’s exposure to different asset classes based on short-term expectations. This can be especially relevant during transitions between bull and bear markets.

3.3 Dynamic Asset Allocation:

3.3.1 Balancing Long-Term Goals with Short-Term Adaptability:

- Hybrid Approach: Dynamic asset allocation combines elements of both strategic and tactical approaches. It seeks to balance the long-term focus of strategic allocation with the adaptability of tactical allocation to changing market conditions.

- Incorporating Economic Indicators: Dynamic asset allocators often incorporate economic indicators, valuation metrics, and market sentiment into their decision-making process. This allows for a more nuanced approach to portfolio management.

3.3.2 Risk Management through Flexibility:

- Risk-Responsive Strategies: Dynamic asset allocation strategies are designed to be responsive to shifts in market risk. This responsiveness can be particularly advantageous during periods of economic turbulence or when traditional correlations between asset classes may be disrupted.

- Regular Monitoring and Adjustments: Regular monitoring of economic indicators and portfolio performance enables dynamic asset allocators to make timely adjustments. This proactive approach is aimed at optimizing the risk-return profile over time.

Assessing the historical performance of these traditional asset allocation strategies across various economic environments provides valuable insights into their effectiveness and limitations.

Section 4: Factor-Based Asset Allocation Strategies:

Factor-based asset allocation strategies depart from the traditional emphasis on asset classes and instead focus on specific factors that drive returns. Two notable approaches in this category are Risk Parity and Smart Beta, each offering a unique perspective on constructing portfolios.

4.1 Risk Parity:

4.1.1 Balancing Portfolios Based on Risk, Not Market Capitalization:

- Fundamental Principle: Risk parity allocates capital based on risk rather than traditional market capitalization weights. The goal is to create a balanced portfolio where each asset class contributes equally to the overall risk, mitigating the risk of overconcentration in any single asset.

- Risk Contributions: In a risk parity portfolio, assets with lower volatility may receive higher allocations, while riskier assets receive lower allocations. This approach seeks to achieve a more balanced risk contribution from each asset class.

4.1.2 Performance in Bull and Bear Markets:

- Bull Markets: During bull markets, risk parity portfolios may benefit from the positive performance of equities, but with a more balanced risk exposure. The strategy aims to reduce the impact of a potential market downturn on the overall portfolio.

- Bear Markets: In bear markets, the emphasis on risk diversification may help protect capital. While the strategy does not guarantee immunity from losses, the diversified risk approach aims to provide more stable returns during turbulent market conditions.

4.2 Smart Beta Strategies:

4.2.1 Alternative Index Construction Rules to Capture Factors:

- Beyond Market Capitalization: Smart beta strategies involve using alternative index construction rules to capture specific factors such as value, momentum, low volatility, or quality. This departure from traditional market-cap-weighted indices aims to generate excess returns or reduce risk.

- Factor Exposure: Different smart beta strategies provide exposure to specific factors. For example, a value-focused smart beta strategy may overweight stocks with lower valuations, while a low volatility strategy may prioritize stocks with lower price fluctuations.

4.2.2 Performance Across Economic Environments:

- Value Factors in Economic Expansions: Value-oriented smart beta strategies may outperform during economic expansions, as undervalued stocks have the potential to experience higher growth. These strategies often capitalize on market inefficiencies and mispricing.

- Low Volatility in Economic Contractions: Conversely, low volatility strategies may shine during economic contractions. Investors seeking stability may find these strategies appealing as they prioritize stocks with historically lower price fluctuations.

- Adapting to Market Conditions: The adaptability of smart beta strategies allows investors to tailor their factor exposure based on prevailing economic conditions, providing a dynamic approach to portfolio construction.

Understanding how risk parity and smart beta strategies perform across various economic environments provides investors with insights into the potential benefits and challenges associated with factor-based asset allocation.

Section 5: Alternative Investments:

Alternative investments, such as real assets and hedge funds, play a distinct role in portfolio diversification, offering potential returns that may not correlate with traditional asset classes. Examining their performance across diverse economic environments sheds light on their effectiveness in enhancing portfolio resilience and managing risk.

5.1 Real Assets:

5.1.1 Diversification Benefits and Inflation Hedge:

- Real Estate: Investing in real estate provides diversification benefits as it often exhibits a low correlation with traditional asset classes. Real estate values may appreciate independently of stock and bond market movements.

- Inflation Hedge: Real assets, including commodities, have historically served as a hedge against inflation. Tangible assets like precious metals and commodities may retain value or even appreciate during periods of rising prices.

5.1.2 Performance in Bull, Bear, and Inflationary Environments:

- Bull Markets: Real assets, particularly real estate, may benefit from positive economic conditions during bull markets. Increased demand for properties and infrastructure development can contribute to value appreciation.

- Bear Markets: While real assets are not immune to economic downturns, their lower correlation with traditional assets may provide some downside protection. Tangible assets like farmland or infrastructure projects may maintain value during bear markets.

- Inflationary Environments: Real assets, especially commodities, tend to perform well during inflationary periods. The intrinsic value of physical assets can rise as the purchasing power of currencies declines.

5.2 Hedge Funds:

5.2.1 Diverse Strategies for Market Outperformance:

- Long-Short Equity: Hedge funds often employ long-short equity strategies, allowing them to profit from both rising and falling stock prices. This flexibility enables managers to navigate changing market conditions.

- Global Macro: Global macro hedge funds take a macroeconomic approach, making bets on broad economic trends and global events. This strategy allows for a diversified set of investments, potentially benefiting from various economic environments.

5.2.2 Performance during Market Volatility and Uncertainty:

- Market-Neutral Strategies: Certain hedge funds employ market-neutral strategies, aiming to generate returns irrespective of market direction. These strategies can be particularly valuable during periods of heightened market volatility and uncertainty.

- Diversification from Traditional Investments: Hedge funds’ ability to invest across a wide range of asset classes and employ various strategies provides an additional layer of diversification, potentially reducing overall portfolio risk.

5.2.3 Challenges and Considerations:

- Fee Structure: Hedge funds often charge performance fees in addition to management fees. Investors should carefully evaluate the fee structure and weigh potential returns against costs.

- Liquidity Concerns: Some hedge fund strategies may involve less liquid assets, potentially impacting an investor’s ability to quickly access their capital. This illiquidity should be considered in the context of an investor’s overall portfolio needs.

Understanding how real assets and hedge funds perform in different economic environments allows investors to assess their role in a well-rounded portfolio.

Section 6: The Rise of ESG Investing:

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing has gained significant traction in recent years as investors increasingly seek to align their portfolios with ethical, social, and environmental considerations. Evaluating the performance of ESG-focused portfolios across diverse economic environments provides insights into their potential to deliver financial returns while promoting positive societal impact.

6.1 Principles of ESG Investing:

6.1.1 Environmental Factors:

- Climate Impact: ESG investors consider a company’s environmental impact, including its carbon footprint, use of renewable resources, and efforts to mitigate climate change. This aligns with the growing global emphasis on sustainability.

- Resource Efficiency: Companies focusing on efficient resource utilization, waste reduction, and sustainable supply chain practices are often favored by ESG investors.

6.1.2 Social Factors:

- Labor Practices: ESG considerations encompass labor practices, including fair wages, workplace safety, and diversity and inclusion initiatives. Companies demonstrating commitment to these principles are viewed positively.

- Community Engagement: ESG investors value companies that actively engage with and contribute positively to the communities in which they operate.

6.1.3 Governance Factors:

- Board Structure and Accountability: Effective governance is a cornerstone of ESG investing. Investors assess the structure and accountability of a company’s board, including the presence of independent directors and mechanisms for shareholder rights.

- Ethical Business Practices: Companies adhering to ethical business practices, transparent reporting, and anti-corruption measures are often favored by ESG investors.

6.2 Performance of ESG Portfolios Across Economic Environments:

6.2.1 Bull Markets:

- Outperformance Potential: ESG-focused companies may outperform during bull markets as they often demonstrate strong fundamentals, including effective governance, responsible business practices, and strategic adaptation to emerging environmental and social trends.

- Consumer Preferences: Positive ESG performance may resonate with consumers during periods of economic growth, leading to increased brand loyalty and market share for companies prioritizing sustainability.

6.2.2 Bear Markets:

- Resilience and Stability: ESG portfolios may exhibit resilience during bear markets due to their focus on companies with strong governance and risk management practices. This stability can be attractive to investors seeking to mitigate losses during economic downturns.

- Long-Term Focus: ESG investing is often characterized by a long-term perspective, with an emphasis on sustainable practices. This long-term focus may contribute to the stability of ESG portfolios during periods of market turbulence.

6.2.3 Economic Recessions:

- Adaptability and Risk Management: ESG factors are integral to risk management, and companies with strong ESG practices may demonstrate better adaptability during economic recessions. Effective governance and ethical business practices can contribute to strategic decision-making in challenging economic environments.

- Investor Demand: The increasing demand for ESG investments, even during economic downturns, may contribute to the resilience of ESG-focused portfolios. As more investors prioritize sustainability, the demand for ESG assets may remain robust.

6.3 Challenges and Considerations in ESG Investing:

6.3.1 Data Quality and Standardization:

- Lack of Uniform Standards: The lack of standardized ESG reporting frameworks can make it challenging to compare the ESG performance of different companies. Efforts to establish industry-wide standards are ongoing.

- Data Accuracy: The accuracy and reliability of ESG data can vary, impacting the ability of investors to make informed decisions. Ongoing improvements in data quality are essential for the continued growth of ESG investing.

6.3.2 Integration with Traditional Metrics:

- Balancing Financial and ESG Metrics: Integrating ESG factors with traditional financial metrics poses a challenge. Striking the right balance between financial performance and ethical considerations requires careful consideration and evolving analytical tools.

- Quantifying Impact: Measuring the actual impact of ESG practices on financial performance can be complex. Investors are increasingly seeking ways to quantify the tangible benefits of incorporating ESG criteria into their investment decisions.

In conclusion, constructing a resilient investment portfolio requires a nuanced understanding of different asset allocation strategies and their effectiveness across diverse economic environments. Strategic, tactical, dynamic, factor-based, and alternative approaches each have their merits and drawbacks. As investors navigate the complex seas of the global economy, a thoughtful combination of these strategies, tailored to individual risk preferences and financial goals, can help weather the storms and capitalize on the opportunities that arise.

References:

- Markowitz, H. (1952). “Portfolio Selection.” The Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77-91.

- Ibbotson, R. G., & Kaplan, P. D. (2000). “Does Asset Allocation Policy Explain 40, 90, or 100 Percent of Performance?” Financial Analysts Journal, 56(1), 26-33.

- Brinson, G. P., Hood, L. R., & Beebower, G. L. (1986). “Determinants of Portfolio Performance.” Financial Analysts Journal, 42(4), 39-44.

- Siegel, J. J. (2003). “Stocks for the Long Run: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns and Long-Term Investment Strategies.” McGraw-Hill Education.

- Shiller, R. J. (2015). “Irrational Exuberance.” Princeton University Press.

- Gorton, G., & Rouwenhorst, K. G. (2004). “Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures.” Financial Analysts Journal, 60(6), 47-68.

- Statman, M. (2011). “Behavioral Finance: The Second Generation.” SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Qian, E., Hua, R., & Belton, B. (2012). “Risk Parity, Demystified.” The Journal of Portfolio Management, 39(1), 60-68.

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). “Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds.” Journal of Financial Economics, 33(1), 3-56.

- Arnott, R., Hsu, J., & Moore, P. (2005). “Fundamental Indexation.” Financial Analysts Journal, 61(2), 83-99.

- National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries (NCREIF). (2021). “NCREIF Property Index (NPI).”

- Swensen, D. F. (2009). “Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment.” Free Press.

- Ang, A., Goetzmann, W. N., & Schaefer, S. M. (2009). “Evaluation of Active Management of the Norwegian Government Pension Fund—Global.” Norges Bank Working Paper.

- Lhabitant, F. S. (2001). “Hedge Funds: Myths and Limits.” John Wiley & Sons.

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). “ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from More than 2000 Empirical Studies.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 5(4), 210-233.

- Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). (2018). “Annual Impact Investor Survey.” Retrieved from https://thegiin.org/research/publication/annualsurvey2018/

Assistant Teacher at Zinzira Pir Mohammad Pilot School and College