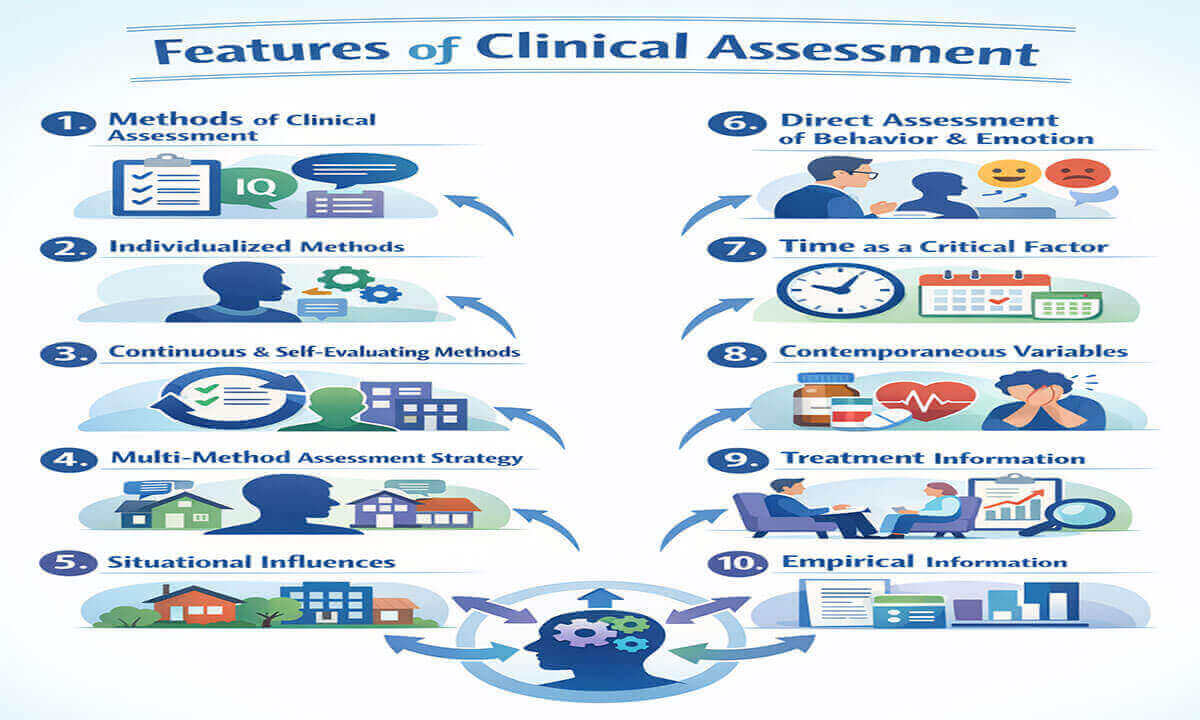

Key Features of Clinical Assessment:

Clinical assessment is a foundational process in psychology, psychiatry, and mental health care that involves systematically gathering information about an individual’s psychological functioning, emotional state, behavior patterns, and contextual influences. Unlike simple testing, clinical assessment is a dynamic, integrative, and hypothesis-driven process designed to understand the client as a whole person rather than as a collection of symptoms (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016). Effective clinical assessment informs diagnosis, treatment planning, risk evaluation, and outcome monitoring. To achieve these goals, clinicians rely on multiple features that ensure accuracy, relevance, and ethical practice. These features include diverse assessment methods, individualized and continuous evaluation, sensitivity to situational and temporal factors, direct observation of behavior and emotion, and reliance on empirical evidence. This article explores the key features of clinical assessment, highlighting their importance in delivering valid, reliable, and person-centered mental health care.

1. Methods of Clinical Assessment: Clinical assessment relies on a systematic use of multiple methods to gather accurate and comprehensive information about an individual’s psychological functioning. These methods commonly include clinical interviews, psychological tests, behavioral observations, self-report measures, and collateral information (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016).

The clinical interview is often the starting point of assessment. Through structured, semi-structured, or unstructured interviews, clinicians explore presenting problems, symptom history, personal background, mental status, and psychosocial factors. Psychological tests (such as intelligence tests, personality inventories, or symptom checklists) provide standardized data that help compare an individual’s functioning with normative populations. Behavioral observation allows clinicians to directly examine how clients act, communicate, and regulate emotions in real or simulated settings.

Example: A clinician assessing a university student for depression may use a semi-structured interview to explore mood symptoms, administer a standardized depression scale (such as the Beck Depression Inventory), observe the student’s affect and speech during sessions, and gather collateral information from academic records or family members. Using multiple methods increases accuracy and reduces reliance on a single source of information (Hunsley & Mash, 2007).

Usually, the use of diverse methods strengthens clinical judgment and enhances the validity and reliability of assessment findings.

2. Individualized Methods: A core feature of clinical assessment is that it must be individualized to the client’s unique characteristics and context. No assessment method is universally appropriate for all individuals. Clinicians must adapt their tools and approaches based on factors such as age, culture, language, education, cognitive abilities, and presenting problems (American Psychological Association [APA], 2017).

Individualization ensures that assessment results are meaningful and ethically sound. Standardized tests may not fully capture a person’s experiences if cultural norms, literacy levels, or developmental stages are ignored. Tailoring assessment methods also helps build rapport and increases client engagement in the assessment process.

Example: When assessing a child with suspected attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a clinician may rely more on behavioral observations, teacher reports, and parent interviews rather than lengthy self-report questionnaires. In contrast, when assessing an adult client with anxiety, self-report scales and detailed clinical interviews may be more appropriate. Adapting methods to the individual improves diagnostic accuracy and fairness (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016).

Thus, individualized assessment reflects a person-centered approach that respects diversity and supports accurate clinical understanding.

3. Continuous and Self-Evaluating Methods: Clinical assessment is best understood as a continuous and self-evaluating process, rather than a one-time event. Psychological functioning can change over time due to treatment, life events, or developmental factors. Therefore, clinicians must regularly reassess clients to monitor progress, evaluate treatment effectiveness, and revise clinical hypotheses when necessary (Persons, 2008).

Self-evaluation is equally important in this process. Clinicians must critically reflect on their interpretations, remain aware of potential biases, and consider alternative explanations for observed behaviors or symptoms. This reflective practice supports ethical responsibility and improves clinical decision-making.

Example: A therapist working with a client diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder may conduct periodic symptom assessments during therapy sessions. If anxiety scores remain unchanged after several weeks of treatment, the clinician may reconsider the treatment approach or reassess contributing factors such as stress, medication effects, or comorbid conditions. This ongoing evaluation ensures that treatment remains responsive and evidence-based (Kazdin, 2008).

Continuous and self-evaluating assessment allows clinicians to adapt to change, improve outcomes, and maintain professional accountability.

4. Multi-Method Assessment Strategy: A multi-method assessment strategy refers to the systematic use of multiple assessment techniques to understand an individual’s psychological functioning. Rather than relying on a single source of data, clinicians integrate information from interviews, standardized tests, behavioral observations, self-reports, and collateral sources to form a comprehensive clinical picture (Meyer et al., 2001).

This approach is based on the principle of converging evidence, where findings from different methods support or clarify one another. When results across methods are consistent, confidence in the assessment increases. When discrepancies appear, they provide valuable insights into situational factors, response biases, or underlying psychological processes.

Example: A clinician assessing a client for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may combine a trauma-focused clinical interview, standardized PTSD symptom scales, direct observation of emotional responses during sessions, and reports from family members. If the client minimizes symptoms in self-reports but shows intense emotional distress during interviews, the discrepancy highlights avoidance or lack of insight, which is clinically meaningful (Hunsley & Mash, 2007).

Generally, a multi-method strategy enhances diagnostic accuracy, reduces assessment bias, and supports evidence-based clinical decision-making.

5. Situational Influences: Clinical assessment must consider situational and environmental influences that shape behavior and emotional responses. Psychological functioning does not occur in isolation; it is influenced by family relationships, social roles, cultural expectations, occupational demands, and life stressors (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

Symptoms may vary significantly across different contexts. Behaviors that appear problematic in one setting may be adaptive in another. Ignoring situational factors can lead to misinterpretation of symptoms and inappropriate diagnoses.

Example: A child who exhibits aggressive behavior at school but not at home may be responding to peer conflict, academic pressure, or classroom structure rather than an underlying conduct disorder. Similarly, an adult who experiences anxiety only in work environments may be reacting to job-related stress rather than having a generalized anxiety disorder. Assessing situational influences allows clinicians to understand the context-specific nature of symptoms (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016).

By incorporating environmental context, clinicians ensure that assessment findings are accurate, meaningful, and ethically grounded.

6. Direct Assessment of Behavior and Emotion: Another critical feature of clinical assessment is the direct assessment of behavior and emotion. Rather than relying solely on what clients report about themselves, clinicians observe how individuals behave, communicate, and express emotions in real-time or structured settings (Haynes and O’Brien, 2000).

Direct observation provides access to nonverbal behavior, emotional regulation, interpersonal style, and coping strategies. It is especially valuable when clients have limited insight, difficulty verbalizing emotions, or tendencies to underreport or exaggerate symptoms.

Example: During an assessment session, a clinician may observe a client who reports feeling “calm” but displays trembling hands, avoidance of eye contact, and a strained voice. These observable behaviors suggest underlying anxiety that may not be fully captured through self-report measures alone. In child assessments, direct observation during play or classroom activities often reveals emotional and behavioral patterns that standardized tests cannot detect.

Direct assessment increases ecological validity and strengthens the overall quality of clinical judgment.

7. Time as a Critical Factor: Time is a crucial dimension in clinical assessment because psychological symptoms and behaviors change across different time periods. Clinicians must consider the onset, duration, frequency, and progression of symptoms to understand their clinical significance (Kazdin, 2003).

Short-term emotional reactions to stress (such as sadness after a loss or anxiety before an exam) are often normal and adaptive. In contrast, persistent or worsening symptoms over long periods may indicate a psychological disorder. Developmental timing is also essential, as behaviors appropriate at one life stage may be problematic at another.

Example: A teenager who experiences mood swings for a few weeks following academic failure may be showing a situational reaction. However, if low mood, withdrawal, and hopelessness persist for several months, this pattern may suggest major depressive disorder. Similarly, bedwetting is developmentally normal in early childhood but becomes clinically concerning in adolescence. Longitudinal assessment allows clinicians to distinguish between temporary reactions and enduring psychological conditions (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016).

Considering time improves diagnostic accuracy and prevents overpathologizing normal human experiences.

8. Contemporaneous Variables: Contemporaneous variables are factors present at the time of assessment that can influence an individual’s behavior, emotional state, or test performance. These include physical health conditions, medication effects, substance use, fatigue, sleep deprivation, and current stress levels (Hunsley & Mash, 2007).

Failure to consider these variables can lead to inaccurate interpretations and flawed clinical conclusions. A client’s current state may not reflect their typical functioning, but rather a temporary condition affecting performance or mood.

Example: A client assessed for cognitive difficulties may perform poorly on memory tasks due to lack of sleep or side effects of medication rather than an underlying neuropsychological disorder. Similarly, elevated anxiety scores may reflect acute stress related to a recent life event, such as job loss or family conflict, rather than a chronic anxiety disorder. Identifying contemporaneous variables ensures that assessment results are interpreted within the appropriate context (Kazdin, 2003).

Accounting for these factors enhances ethical responsibility and clinical precision.

9. Treatment Information: Clinical assessment plays an essential role in treatment planning and evaluation. Assessment findings guide clinicians in selecting appropriate interventions, setting therapeutic goals, and establishing baseline measures against which progress can be evaluated (Kazdin, 2008).

Assessment continues throughout treatment to monitor outcomes and determine whether interventions are effective. If progress is limited, clinicians may revise the treatment plan, reassess diagnoses, or explore additional contributing factors.

Example: A clinician working with a client diagnosed with panic disorder may use initial assessment data to determine the severity and frequency of panic attacks. During treatment, repeated assessments help evaluate whether cognitive-behavioral techniques are reducing symptoms. If panic episodes persist, the clinician may adjust therapeutic strategies or consider pharmacological consultation. This ongoing feedback strengthens the link between assessment and intervention (Persons, 2008).

Using assessment as a treatment tool ensures that clinical practice remains responsive, flexible, and evidence-based.

10. Empirical Information: A fundamental feature of modern clinical assessment is its grounding in empirical information. Evidence-based assessment emphasizes the use of scientifically validated tools, research findings, and standardized procedures to ensure reliability, validity, and clinical utility (Hunsley & Mash, 2007). Clinicians combine empirical evidence with clinical expertise and client characteristics to make informed, objective decisions.

Empirical grounding helps reduce subjective bias, prevents overreliance on intuition, and ensures that assessment practices meet professional and ethical standards. It also allows clinicians to compare a client’s performance or symptoms with normative data or research benchmarks, strengthening the accuracy of diagnoses and treatment planning.

Example: When assessing depression, a clinician may administer the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), a widely validated self-report measure, rather than relying solely on casual observation. The results are interpreted based on normative scores, research on clinical thresholds, and the client’s specific context. Similarly, neuropsychological assessments, such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV), provide empirically derived scores that help identify cognitive strengths and weaknesses relative to the population (Groth-Marnat & Wright, 2016).

Integrating empirical information ensures that clinical assessment is scientifically sound, replicable, and ethically responsible, supporting effective intervention and optimal client outcomes.

In conclusion, clinical assessment is a complex, integrative, and evolving process that lies at the heart of effective mental health practice. Its key features (diverse methods, individualization, continuous evaluation, multi-method strategies, attention to situational and temporal factors, direct observation, consideration of contemporaneous variables, treatment relevance, and empirical grounding) work together to create a holistic understanding of the client. When applied thoughtfully and ethically, clinical assessment moves beyond diagnosis to inform meaningful intervention, promote client well-being, and support evidence-based care. In an increasingly diverse and dynamic clinical landscape, these features ensure that assessment remains scientifically sound, person-centered, and clinically effective.

References:

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. APA.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Groth-Marnat, G., & Wright, A. J. (2016). Handbook of psychological assessment (6th ed.). Wiley.

- Haynes, S. N., & O’Brien, W. H. (2000). Principles and practice of behavioral assessment. Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

- Hunsley, J., & Mash, E. J. (2007). Evidence-based assessment. Annual review of clinical psychology, 3, 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091419

- Kazdin, A. E. (2003). Research Design in Clinical Psychology (4th ed.). London: Pearson.

- Kazdin, A. E. (2008). Evidence-based treatment and practice: New opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. American Psychologist, 63(3), 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146

- Meyer, G. J., Finn, S. E., Eyde, L. D., Kay, G. G., Moreland, K. L., Dies, R. R., Eisman, E. J., Kubiszyn, T. W., & Reed, G. M. (2001). Psychological testing and psychological assessment. A review of evidence and issues. The American psychologist, 56(2), 128–165.

- Persons, J. B. (2008). The case formulation approach to cognitive-behavior therapy. The Guilford Press.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College