The Herbartian Approach to Lesson Planning:

Lesson planning is an essential aspect of effective teaching and learning. Among the various approaches that have shaped modern pedagogical practices, the Herbartian Approach stands out for its systematic, structured, and psychological basis. Developed by the German philosopher and educationist Johann Friedrich Herbart (1776–1841), this approach laid the foundation for scientific lesson planning during the 19th century. Herbart emphasized the need for organized instruction rooted in the psychology of learning, believing that well-structured teaching leads to effective knowledge acquisition and moral development. This article explores the Herbartian approach to lesson planning, including its meaning, steps, advantages, and criticisms, highlighting its continued relevance in education.

Understanding the Herbartian Approach:

Johann Friedrich Herbart is often regarded as the father of scientific pedagogy. His educational philosophy was built on two core ideas: apperception (the process by which new ideas are assimilated with existing knowledge) and interest (the role of student motivation). According to Herbart, learning happens when teachers connect new knowledge with students’ prior knowledge in a logical and psychological order.

Herbart stressed that lesson planning should not be a random sequence of activities but rather follow a definite structure. This structure ensures that lessons progress systematically, catering to students’ mental processes and fostering holistic understanding.

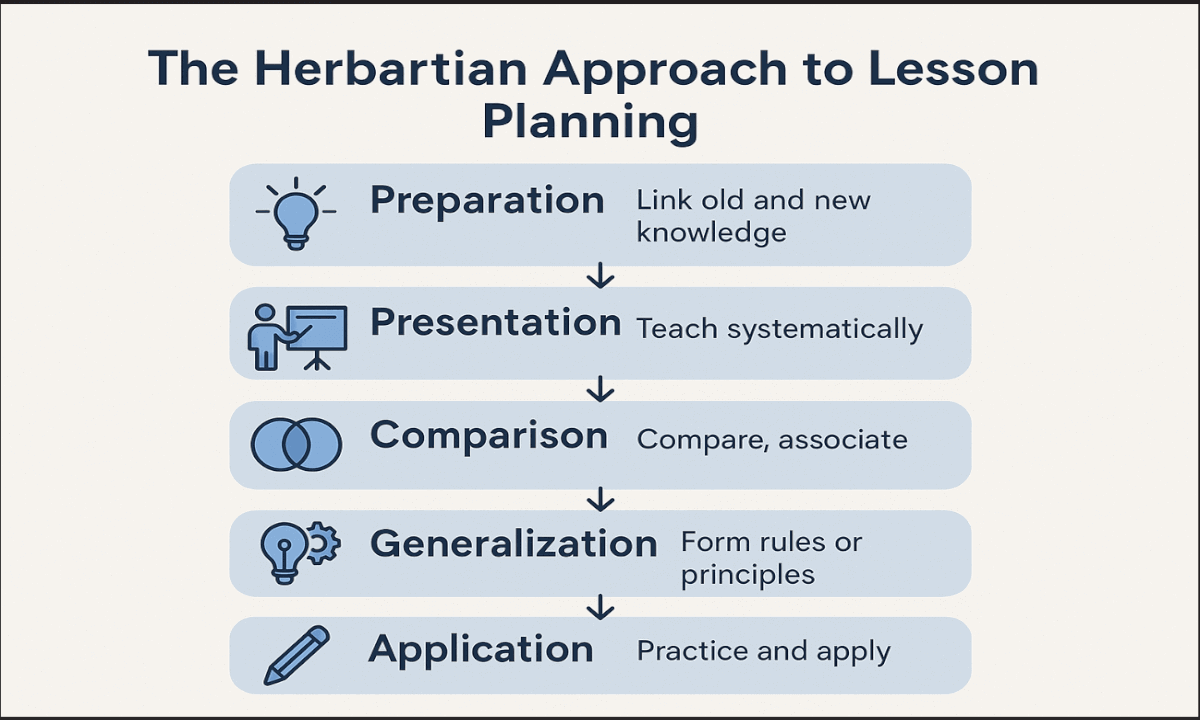

Five Formal Steps of the Herbartian Approach:

The heart of the Herbartian approach lies in its clear, logical sequence of five steps. Herbart believed that the mind processes new knowledge in a definite way, and teachers should structure their lessons to align with this natural mental process. Each step has a specific role in ensuring that students understand, internalize, and apply what they learn.

1. Preparation (Introduction): The first step is to prepare students’ minds to receive new knowledge. Herbart emphasized that learning cannot happen in a vacuum—students need a mental bridge connecting what they already know with what they are about to learn.

Key features:

- Activate students’ prior knowledge.

- Capture their interest and curiosity.

- Set a clear purpose for the lesson.

How it works: Teachers might use questions, real-life situations, anecdotes, or simple discussions to connect the topic to students’ experiences. This helps create a mental readiness for new information.

Example: Before teaching about the water cycle, a teacher might ask, “Where does rain come from? Have you ever seen puddles disappear on a sunny day?” This primes students to think about evaporation and condensation.

2. Presentation: In this step, the teacher introduces the new knowledge or concept in a clear, organized, and systematic manner. Herbart argued that clear presentation prevents confusion and ensures that students grasp the material thoroughly.

Key features:

- Use simple language and step-by-step explanation.

- Employ teaching aids (charts, models, visuals, experiments).

- Engage multiple senses where possible.

How it works: Teachers should present facts logically, from simple to complex, concrete to abstract, or known to unknown.

Example: When explaining photosynthesis, the teacher might show a diagram of a leaf, explain the role of sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water, and even perform a simple experiment showing oxygen bubbles in water plants.

3. Comparison (Association): The third step involves helping students compare, associate, or relate new ideas to what they already know. This mental process is what Herbart called apperception—the merging of new and old knowledge.

Key features:

- Highlight similarities and differences.

- Encourage students to find connections.

- Use analogies and examples.

How it works: Teachers ask probing questions to help students link the new concept to previous lessons or real-life experiences.

Example: After learning about photosynthesis, students might compare it to how humans eat food. A teacher could ask, “How is a plant making food like you eating your lunch? What’s different?”

4. Generalization: Once students have compared and analyzed the new information, they are guided to generalize. This means they draw conclusions, formulate rules, or develop general statements from specific facts.

Key features:

- Guide students to find key principles.

- Encourage students to express ideas in their own words.

- Reinforce understanding of broader concepts.

How it works: Teachers pose higher-order questions that help students arrive at general rules or statements.

Example: After comparing plants and animals, students might conclude, “Green plants are producers because they make their own food using sunlight.” This generalization ties the specific lesson to a broader scientific concept.

5. Application: The final step is applying the acquired knowledge to new situations. This checks understanding, reinforces learning, and develops students’ ability to use knowledge in real life.

Key features:

- Provide exercises, problem-solving tasks, or practical activities.

- Encourage students to apply concepts in familiar or novel contexts.

- Assess understanding through questions or activities.

How it works: Students may do written exercises, projects, experiments, or answer questions that require them to use what they have learned.

Example: After a lesson on the water cycle, students might be asked to explain why clothes dry faster in the sun, or create a simple diagram showing evaporation and condensation in everyday life.

Summary of the Five Steps:

| Step | Purpose | Key Activity |

| Preparation | Ready the mind | Link old and new knowledge |

| Presentation | Introduce new ideas | Teach systematically |

| Comparison | Relate ideas | Compare, associate |

| Generalization | Conclude | Form rules or principles |

| Application | Use knowledge | Practice and apply |

Herbart’s five steps remain influential because they align with how people naturally process information: preparing the mind, presenting new ideas, connecting them to existing knowledge, drawing conclusions, and applying the learning. This simple yet structured flow makes lessons logical, meaningful, and memorable for students.

Merits of the Herbartian Approach:

The Herbartian approach to lesson planning holds an important place in the history of educational methods. Despite being developed in the 19th century, its strengths continue to inform modern teaching practices. The approach’s structured and systematic nature, emphasis on psychological principles, and logical sequence offer several distinct advantages for both teachers and students. Here are its main merits in detail:

i. Systematic and Logical Sequence: One of the utmost strengths of the Herbartian approach is its clear, step-by-step progression. By following the five formal steps—Preparation, Presentation, Comparison, Generalization, and Application—teachers ensure that lessons are delivered in a coherent and logical order.

Why it’s beneficial:

- Helps teachers avoid haphazard teaching.

- Ensures that each part of the lesson builds upon the previous one.

- Makes complex concepts easier to understand by breaking them down into smaller, manageable parts.

Example: In a science lesson on the water cycle, the teacher first connects students’ prior knowledge (Preparation), explains the stages with visuals (Presentation), relates it to daily experiences like drying clothes (Comparison), helps students derive the general principle (Generalization), and finally asks them to apply it to explain real-life phenomena (Application).

ii. Psychological Basis: Herbart’s approach was one of the first to integrate the psychology of learning into lesson planning. The concept of apperception—linking new knowledge to existing ideas—reflects how the human mind naturally learns.

Why it’s beneficial:

- Takes students’ mental processes into account.

- Makes learning meaningful rather than rote.

- Encourages teachers to consider students’ prior knowledge, interest, and readiness.

Example: Before introducing fractions, a math teacher might connect the idea to students’ experiences of sharing pizza slices or chocolates, making abstract concepts relatable and easier to grasp.

iii. Promotes Student Engagement: The Herbartian approach emphasizes active student participation through questioning, discussion, and practical activities, especially in the Preparation, Comparison, and Application steps.

Why it’s beneficial:

- Prevents passive listening and rote memorization.

- Engages students’ curiosity and critical thinking.

- Builds connections between theory and real-life experiences.

Example: Students may compare different animal habitats after learning about ecosystems, discuss similarities, and generalize about how living conditions affect survival.

iv. Develops Higher-Order Thinking: Through the steps of Comparison and Generalization, students are guided to analyze, compare, draw conclusions, and generalize ideas. This fosters analytical and critical thinking skills rather than mere memorization.

Why it’s beneficial:

- Encourages logical reasoning and deeper understanding.

- Helps students see patterns and principles behind facts.

- Prepares students to solve problems and think independently.

Example: After comparing local and international climates, students may generalize that climate influences vegetation and lifestyle, applying this understanding to interpret geographical data.

v. Practical Guidance for Teachers: For new or inexperienced teachers, the Herbartian approach serves as a clear framework to plan lessons confidently and systematically.

Why it’s beneficial:

- Provides structure and reduces guesswork.

- Helps teachers manage time effectively.

- Makes it easier to evaluate whether lesson objectives are met.

Example: A trainee teacher can use the five steps as a checklist to ensure that their lesson moves from preparation to application without skipping essential parts.

vi. Foundation for Modern Lesson Planning: The Herbartian model laid the groundwork for later instructional theories and models like Bloom’s Taxonomy, RCEM, and the 5E Instructional Model. The enduring idea of moving from known to unknown, simple to complex, and concrete to abstract can be traced back to Herbart’s influence.

Why it’s beneficial:

- Offers a timeless framework adaptable to modern classrooms.

- Encourages integration with new teaching strategies, such as activity-based or constructivist learning.

- Promotes reflective teaching practices.

Limitations of the Herbartian Approach:

While the Herbartian approach to lesson planning played a pivotal role in shaping structured, scientific teaching, it has also faced significant criticisms over time. Many modern educators argue that its rigid, teacher-centered framework does not fully align with contemporary ideas about how students learn best. Here are the main limitations of the Herbartian approach, explained in detail:

i. Overly Rigid and Mechanical: One major criticism is that the Herbartian approach can become too rigid and mechanical when followed strictly. The fixed sequence of five steps—Preparation, Presentation, Comparison, Generalization, and Application—may not suit every subject, lesson, or age group.

Why this is a problem:

- Not all learning situations can be broken down neatly into five formal steps.

- It may force teachers to stick to the sequence even when flexibility is needed.

- Creative, spontaneous teaching moments can be stifled.

Example: In art or music lessons, where exploration and creativity are central, imposing a rigid structure can limit students’ free expression.

ii. Teacher-Centered, Not Learner-Centered: The Herbartian approach is largely teacher-directed. The teacher plans, presents, explains, and controls each step, leaving students mostly in the role of passive receivers rather than active participants.

Why this is a problem:

- Modern education emphasizes active, student-centered learning.

- It does not fully encourage discovery learning, collaboration, or student choice.

- Students may become dependent on the teacher instead of developing self-directed learning skills.

Example: In an inquiry-based science lesson, students might learn better by conducting experiments themselves rather than only listening to the teacher’s step-by-step presentation.

iii. Neglects Individual Differences: Herbart’s model assumes that all students in the classroom can learn the same content in the same way and at the same pace. It does not account for differences in learning styles, abilities, interests, or backgrounds.

Why this is a problem:

- Students have diverse needs and preferences.

- Some may need more time or alternative methods to grasp concepts.

- The “one-size-fits-all” approach can leave weaker students behind or bore advanced learners.

Example: A student who struggles with language might find it hard to follow a lesson that heavily relies on verbal presentation and teacher explanation without varied activities or differentiated tasks.

iv. Limited Scope for Activity-Based and Experiential Learning: Modern educational theories emphasize learning by doing, group work, projects, fieldwork, and hands-on activities. The Herbartian approach, however, focuses mainly on teacher explanation and mental processing rather than physical or social activities.

Why this is a problem:

- Children, especially younger ones, learn best through exploration and play.

- Learning experiences outside the classroom (like experiments, outdoor observations, or field trips) don’t fit neatly into Herbart’s five-step model.

- Modern constructivist approaches encourage students to construct knowledge through real-life tasks, which the Herbartian model underemphasizes.

Example: A science teacher may prefer an inquiry-based experiment where students form their own hypotheses rather than passively follow the teacher’s fixed steps.

v. Less Suitable for Skill-Based or Creative Subjects: Subjects that rely heavily on skills, performance, or creativity—such as physical education, drama, art, music, or vocational training—often require flexible, practice-oriented methods rather than formal theoretical steps.

Why this is a problem:

- Skills are often learned through repeated practice, demonstration, and feedback, not rigid steps.

- The model suits theoretical knowledge better than practical skill development.

Example: Teaching swimming or pottery cannot realistically follow a rigid sequence like Preparation–Presentation–Comparison–Generalization–Application.

vi. Does Not Promote Critical Thinking Beyond Generalization: While the Herbartian method does include a step for generalization, it does not deeply cultivate other critical thinking skills like problem-solving, analysis from multiple perspectives, or evaluation of contradictory ideas.

Why this is a problem:

- 21st-century skills require students to tackle complex, ambiguous problems.

- Critical thinking today extends beyond recognizing general principles.

Example: Debating ethical dilemmas in a social studies class often requires students to evaluate, argue, and justify conflicting viewpoints—tasks that are not emphasized in the rigid Herbartian sequence.

Relevance of the Herbartian Approach Today:

Despite being over 180 years old, the Herbartian approach to lesson planning continues to hold practical value in contemporary education, though in an adapted form. While some elements are seen as outdated, many of its core ideas remain deeply embedded in modern teaching methods, curriculum design, and teacher training practices around the world. Here’s why the Herbartian approach still matters today:

A. Foundation for Systematic Lesson Planning: One of the greatest contributions of the Herbartian approach is its insistence on a planned, systematic structure for every lesson. Even today, lesson plans used by teachers, schools, and training institutions worldwide often reflect this principle.

Why it’s relevant:

- It reminds teachers that effective teaching does not happen by chance—it requires preparation and logical organization.

- The concept of sequencing a lesson into phases (introduction, development, conclusion) directly stems from Herbart’s five steps.

- Modern frameworks like Bloom’s Taxonomy, the RCEM approach, and the 5E Model (Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate) echo this step-by-step structure.

B. Psychological Basis and Constructivism: Herbart’s emphasis on apperception—connecting new knowledge with prior knowledge—aligns with modern constructivist theories of learning. Constructivists like Piaget and Vygotsky also stress that learners build new ideas on the foundation of what they already know.

Why it’s relevant:

- Today’s effective teachers begin lessons by activating prior knowledge.

- Methods like mind mapping, brainstorming, KWL charts (What I Know, What I Want to Know, What I Learned) reflect this same principle.

- Linking new concepts to students’ real-life experiences makes learning meaningful and engaging—an idea that Herbart strongly advocated.

C. Emphasis on Active Involvement: Although sometimes viewed as teacher-centered, the Herbartian approach does contain steps—like Comparison and Application—that encourage students to think, analyze, compare, and apply ideas. These align with active learning practices widely used today.

Why it’s relevant:

- Steps like generalization and application promote higher-order thinking, a goal of 21st-century education.

- Teachers still use questions, discussions, and practical tasks to encourage active participation—practices deeply rooted in Herbart’s framework.

- Inquiry-based learning, project-based learning, and problem-solving strategies often begin with similar sequences of preparing, presenting, exploring, and applying knowledge.

D. Use in Teacher Training and Inspections: In many countries, the Herbartian model is still used—at least partly—as a basis for training new teachers on how to plan lessons. Inspectors or school leaders often expect lesson plans to clearly show:

- An introduction to connect with students’ prior knowledge.

- Logical steps for presenting new content.

- Opportunities for practice and application.

Why it’s relevant:

- It gives novice teachers a simple, practical guide to design clear, complete lessons.

- It ensures that important parts of a lesson—motivation, explanation, reinforcement, and practice—are not overlooked.

E. Adaptable for Blended and Modern Contexts: While the original Herbartian approach was developed for traditional classrooms, its principles are often adapted for modern, technology-enhanced learning. For example:

- Preparation can include digital pre-class activities or flipped classroom tasks.

- Presentation can integrate multimedia, interactive simulations, or virtual labs.

- Comparison can happen through online discussions or collaborative digital tools.

- Application may involve real-world projects, digital portfolios, or online assessments.

Why it’s relevant:

- The core steps can easily blend with e-learning, blended learning, and competency-based learning models.

- Teachers can maintain structure while incorporating modern technologies and student-centered strategies.

F. Balancing Structure and Flexibility: Modern education values flexibility and learner autonomy, but a well-structured backbone—like that provided by the Herbartian model—helps balance creativity with clarity.

Why it’s relevant:

- Total freedom without structure can lead to unplanned, ineffective teaching.

- The Herbartian steps remind teachers to maintain a clear instructional flow, even when using flexible, interactive methods.

In conclusion, the Herbartian Approach to lesson planning marks an important milestone in the history of education. By introducing a systematic, psychological, and scientific basis for instruction, Herbart laid the groundwork for modern educational planning. While the rigid structure may not align fully with today’s diverse and dynamic classrooms, the principles of preparation, connection, and application continue to guide effective teaching practices. By blending Herbart’s ideas with flexible, learner-centered methods, educators can create meaningful, engaging, and impactful learning experiences for students.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Who developed the Herbartian approach to lesson planning?

The Herbartian approach was developed by Johann Friedrich Herbart (1776–1841), a German philosopher, psychologist, and educator who is often called the father of scientific pedagogy. He believed in making education systematic and based on psychological principles.

What are the five formal steps in the Herbartian approach?

The five formal steps are:

- Preparation (Introduction) — Prepare students’ minds and connect prior knowledge.

- Presentation — Introduce new knowledge clearly and systematically.

- Comparison (Association) — Relate new knowledge to what is already known.

- Generalization — Guide students to draw general rules or conclusions.

- Application — Help students apply the new knowledge in practical contexts.

Why is the Herbartian approach important in education?

It is important because it introduced a scientific and structured method for lesson planning. It emphasizes logical sequencing, connecting new ideas to prior knowledge, and applying concepts, which are still core principles in modern teaching.

Is the Herbartian approach still relevant today?

Yes, but in an adapted form. While modern education has shifted toward more flexible, learner-centered, and activity-based methods, the Herbartian principles of structured planning, psychological connection, and clear presentation still influence lesson design today.

What are the main advantages of using the Herbartian approach?

Key advantages include:

- Providing a clear, logical sequence for teaching.

- Emphasizing the psychology of learning through apperception.

- Encouraging systematic lesson preparation.

- Laying the foundation for modern lesson planning models.

What are the criticisms of the Herbartian approach?

Critics argue that it:

- Is too rigid and teacher-centered.

- May not fit skill-based or creative subjects.

- Neglects individual learning differences.

- Provides limited scope for discovery learning, hands-on activities, or student-led inquiry.

Can the Herbartian steps be combined with modern teaching methods?

Absolutely. Many teachers adapt the basic sequence while incorporating modern strategies like group work, projects, technology, and inquiry-based learning. The steps can serve as a flexible guide rather than a strict rule.

What kind of lessons are best suited for the Herbartian approach?

It works best for concept-based or theoretical lessons where structured explanation and logical progression are needed—such as in science, social studies, or language lessons focusing on grammar rules.

How can new teachers benefit from the Herbartian approach?

New teachers often find it helpful as a framework for planning lessons clearly and confidently. It ensures that no key part of a lesson—like connecting prior knowledge or checking understanding—is overlooked.

How does the Herbartian approach compare to modern constructivist methods?

Both stress linking new learning to what students already know, but constructivist methods focus more on active exploration, student inquiry, and collaboration, whereas the Herbartian approach emphasizes a more structured, teacher-led sequence.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College