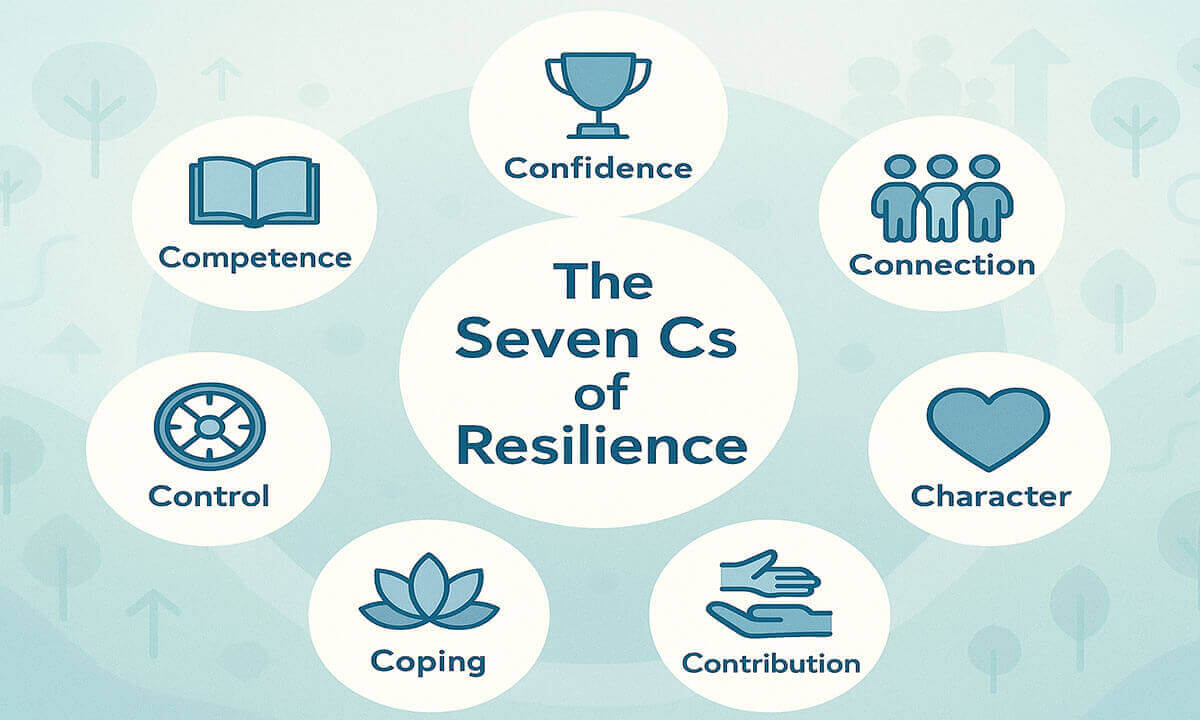

The Seven Cs of Resilience:

Resilience is widely regarded as the ability to adapt successfully in the face of adversity, stress, or trauma. It involves a combination of internal strengths and external resources that help individuals navigate challenges without becoming overwhelmed. One of the most influential frameworks for understanding resilience in youth development is Kenneth Ginsburg’s model of the Seven Cs of Resilience. This framework emphasizes a holistic approach to fostering resilience by integrating competence, confidence, connection, character, contribution, coping, and control (Ginsburg, 2011). Unlike models that focus solely on individual traits, the Seven Cs highlight the importance of family, community, and social support in shaping resilient behaviors.

- Competence: Competence refers to the ability to handle life’s challenges effectively by using one’s knowledge, skills, and judgment. It is not only about having raw ability but also about knowing how and when to apply those abilities in real-world situations. Competence develops when children and adolescents are given opportunities to try new tasks, make mistakes, and learn from them (Ginsburg, 2011).

For example, a child who is encouraged to participate in problem-solving activities, such as organizing a class project, gradually learns to plan, cooperate with peers, and resolve conflicts. These experiences foster a sense of mastery that contributes to resilience. Similarly, a teenager who is allowed to manage their own budget for the first time, under the guidance of parents, gains decision-making skills that will prepare them for adult responsibilities (Masten, 2014).

Research shows that perceived competence acts as a protective factor against risky behaviors. When adolescents feel capable in academics, sports, or social settings, they are less likely to engage in delinquent activities because they derive satisfaction and self-worth from positive achievements (Luthar, 2006). Thus, competence is not innate; it is cultivated by offering consistent opportunities for practice, feedback, and reinforcement.

- Confidence: Confidence is closely related to competence but goes beyond skill; it is the internal belief that one can succeed in facing challenges. Without confidence, even highly skilled individuals may hesitate to take risks or may give up easily in the face of setbacks. Confidence allows individuals to rely on their abilities with courage and persistence (Masten & Tellegen, 2012).

For instance, consider a student who struggles with mathematics. With supportive teachers and tutoring, the student gradually develops the competence to solve equations. As their skills improve, they begin to trust their abilities, which builds confidence. This confidence then encourages the student to attempt more advanced math problems, reinforcing a positive cycle of growth.

On the other hand, excessive criticism or lack of encouragement can undermine confidence. A child who is constantly told that they are “not smart enough” may internalize that belief, leading to self-doubt and avoidance of challenges (Ginsburg, 2015). To prevent this, educators and parents can help children build confidence by acknowledging effort as much as achievement, encouraging resilience in the face of setbacks, and setting realistic but challenging goals.

Confidence plays a vital role in resilience because it empowers individuals to approach life with optimism and perseverance. When people believe in themselves, they are more likely to view failures as temporary and solvable rather than permanent obstacles (Werner & Smith, 2001).

- Connection: Connection highlights the importance of supportive relationships in building resilience. Human beings are social by nature, and strong ties with family, peers, teachers, and community members provide a safety net during times of stress. Research shows that children and adolescents who feel securely connected to their families and communities display greater resilience when facing adversity (Werner & Smith, 2001).

For example, a young person going through parental divorce may experience emotional turmoil. However, if they have a close bond with a teacher or mentor who listens, encourages, and provides stability, they are more likely to adapt positively. Similarly, adolescents who participate in sports teams or youth groups often gain a sense of belonging that buffers against feelings of isolation. These relationships not only provide emotional support but also model coping strategies and reinforce positive values (Masten, 2014).

A lack of connection, on the other hand, can lead to feelings of alienation and increase vulnerability to negative outcomes such as depression, anxiety, or substance abuse. For instance, research on at-risk youth has found that those with supportive peer and adult relationships are significantly less likely to engage in delinquent behavior compared to those without such networks (Luthar, 2006).

Therefore, fostering connection means cultivating safe, stable, and nurturing relationships. Families, schools, and communities can strengthen resilience by promoting open communication, empathy, and opportunities for young people to feel valued and included.

- Character: Character refers to having a strong sense of morality, integrity, and values that guide one’s decisions and interactions with others. It helps individuals differentiate right from wrong and make ethical choices even when faced with peer pressure or adversity (Ginsburg, 2011). Character is not something people are simply born with; it is shaped by families, communities, schools, and cultural traditions that reinforce moral principles.

For example, a teenager who finds a lost wallet in school has a choice: keep the money or return it. If they have developed strong character through family discussions about honesty, school programs emphasizing integrity, and role models who model ethical behavior, they are more likely to make the responsible decision to return the wallet. This sense of doing the right thing, even when it is difficult, strengthens resilience by giving individuals a moral anchor in times of uncertainty.

Research shows that young people with a strong moral identity and a clear sense of values are better equipped to resist negative peer influences, such as pressure to use drugs or engage in delinquency (Luthar, 2006). Moreover, character fosters empathy, helping individuals connect with others and build meaningful relationships (Masten, 2014). In this sense, character not only protects individuals but also contributes to healthier communities.

- Contribution: Contribution highlights the importance of giving back to others and recognizing that one’s actions can positively influence the world. When individuals contribute to their families, schools, or communities, they develop a sense of purpose and belonging, which strengthens resilience (Ginsburg, 2015).

For example, a high school student who volunteers at a local food bank learns firsthand the value of helping others. This experience provides a sense of accomplishment and reinforces the belief that they are capable of making a difference. The act of giving also helps shift focus away from personal struggles toward collective well-being, which can reduce stress and promote positive mental health (Schwartz et al., 2003).

Contribution is especially powerful during adolescence, a time when young people are forming their identities. Research shows that prosocial behaviors, such as volunteering, mentoring, or engaging in community projects, are linked with lower rates of depression and higher levels of life satisfaction (Schwartz et al., 2003). Families and schools can nurture contribution by encouraging children to take responsibility at home, participate in community service, or engage in collaborative projects where their input is valued.

By learning that their contributions matter, young people develop resilience through a greater sense of meaning and interconnectedness. This perspective equips them to face challenges not only as individuals but also as active participants in supportive communities.

- Coping: Coping refers to the strategies and skills individuals use to manage stress, disappointment, and adversity. Effective coping is essential to resilience because it determines whether a person can navigate life’s challenges in a healthy and adaptive way (Compas et al., 2014). Coping strategies can be problem-focused (actively addressing the source of stress) or emotion-focused (managing emotional reactions).

For example, a college student who fails an important exam might respond in different ways. An ineffective coping strategy would be to avoid the issue entirely by engaging in substance use or withdrawing socially. On the other hand, an adaptive coping strategy would be to analyze what went wrong, seek tutoring support, and develop a study plan for improvement. Additionally, they might use emotion-focused coping, such as talking to friends or practicing mindfulness, to manage feelings of disappointment and anxiety.

Teaching coping skills is crucial for young people, as it helps prevent maladaptive behaviors like aggression, self-isolation, or substance misuse (Compas et al., 2014). Schools can promote coping by integrating stress-management workshops, mindfulness practices, and peer support programs into their curricula. Families can help by modeling healthy coping strategies, such as problem-solving conflicts through calm discussion rather than anger.

When individuals are equipped with effective coping tools, they are better prepared to handle inevitable setbacks, thereby strengthening their overall resilience (Masten, 2014).

- Control: Control refers to the belief that individuals can influence what happens in their lives through their own actions and decisions. Psychologists often describe this as an “internal locus of control,” where people believe that their behaviors, rather than luck or external forces, largely determine outcomes (Rotter, 1966). Having a sense of control increases motivation, reduces feelings of helplessness, and strengthens resilience.

For example, consider a high school athlete who loses an important competition. If the athlete believes that success or failure is purely determined by chance, they may feel powerless and discouraged. However, if they believe they can control the outcome by training harder, seeking coaching, and improving techniques, they are more likely to bounce back and remain engaged in their sport.

Research supports that children and adolescents who perceive greater control over their environments are more likely to show persistence in academics, better stress management, and higher overall achievement (Zimmerman, 2000). Conversely, a lack of control can lead to learned helplessness, where individuals stop trying even when opportunities for success exist. Parents, educators, and mentors can encourage a sense of control by allowing young people to make age-appropriate decisions, experience the consequences of their choices, and learn problem-solving strategies.

Cultivating control does not mean teaching young people they can dictate every outcome; rather, it emphasizes that their actions matter. This belief is critical for resilience, as it motivates individuals to take initiative, adapt, and persevere when facing challenges.

In conclusion, the Seven Cs of resilience—Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, Contribution, Coping, and Control—offer a holistic framework for understanding how individuals, especially children and adolescents, can thrive despite adversity. Each “C” builds upon the others: competence fosters confidence; confidence strengthens connection; connection reinforces character; character inspires contribution; contribution enhances coping; and coping supports a sense of control. Together, these qualities form the foundation of resilience.

By integrating these elements, families, educators, and communities can create environments that nurture resilience rather than leaving it to chance. Competence and confidence empower individuals to act effectively, while connection and character anchor them in strong values and relationships. Contribution instills purpose, coping equips them to manage stress, and control provides the belief that their choices matter.

In today’s world, where young people face increasing social, academic, and emotional challenges, the Seven Cs serve as both a roadmap and a toolkit for positive development. Cultivating resilience is not about eliminating hardship but about equipping individuals with the strengths and supports needed to face life’s inevitable difficulties with courage and adaptability. As Ginsburg (2011) emphasizes, resilience grows when young people are given both “roots” to remain grounded and “wings” to pursue their potential.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What are the Seven Cs of resilience?

The Seven Cs of resilience are Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, Contribution, Coping, and Control. This framework, developed by pediatrician Kenneth Ginsburg (2011), provides a holistic approach to strengthening resilience, particularly in children and adolescents.

Why are the Seven Cs important for young people?

They are important because they offer both internal strengths (such as coping and confidence) and external supports (such as connection and contribution) that help young people adapt to challenges. Research shows that resilience is not an inborn trait but a skill that can be nurtured through positive relationships and opportunities for growth (Masten, 2014).

How can parents help children build competence and confidence?

Parents can build competence by providing opportunities for children to try new tasks, solve problems, and learn from mistakes. Confidence grows when parents encourage effort, recognize achievements, and help children see themselves as capable individuals (Ginsburg, 2015).

What role do schools play in fostering resilience?

Schools play a crucial role by promoting supportive teacher-student relationships, offering extracurricular activities that encourage contribution, teaching coping strategies, and creating safe spaces where children can build connection and character (Luthar, 2006).

How can young people develop better coping skills?

Young people can develop coping skills through stress-management techniques such as mindfulness, exercise, journaling, problem-solving, or seeking support from trusted adults and peers. Programs that integrate coping strategies into school curricula have been shown to reduce anxiety and improve resilience (Compas et al., 2014).

What is the difference between confidence and competence?

Competence is the actual ability to do something effectively, while confidence is the belief in one’s ability to succeed. Both are essential for resilience: competence provides the foundation, and confidence ensures individuals trust themselves enough to act (Masten & Tellegen, 2012).

Can resilience be taught, or is it an innate trait?

Resilience is not fixed; it can be taught and strengthened over time. While some personality traits may influence resilience, factors such as supportive relationships, positive role models, and opportunities for growth play a much larger role in building it (Werner & Smith, 2001).

How does contribution enhance resilience?

When individuals contribute to their families, schools, or communities, they develop a sense of purpose and belonging. Acts of contribution, such as volunteering or helping at home, reinforce the idea that they matter and can make a difference, which strengthens resilience (Schwartz et al., 2003).

What does “control” mean in this framework?

Control refers to the belief that one’s actions influence outcomes. Children who develop a sense of control are more motivated, persistent, and less likely to feel helpless in the face of challenges (Rotter, 1966).

Can the Seven Cs be applied to adults as well?

Yes. While the framework was developed with youth in mind, the Seven Cs are universally applicable. Adults benefit from strengthening competence, confidence, connection, character, contribution, coping, and control in order to navigate life transitions, workplace challenges, and personal hardships (Masten, 2014).

References:

- Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Dunbar, J. P., Watson, K. H., Bettis, A. H., Gruhn, M. A., & Williams, E. K. (2014). Coping and Emotion Regulation from Childhood to Early Adulthood: Points of Convergence and Divergence. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(2), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12043

- Ginsburg, K. R. (2011). Building resilience in children and teens: Giving kids roots and wings (2nd ed.). American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Ginsburg, K. R. (2015). Building resilience in children and teens: Giving kids roots and wings (3rd ed.). American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In D. Cicchetti & D. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (2nd ed., pp. 739–795). Wiley.

- Masten, A. S. (2014). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. Guilford Press.

- Masten, A. S., & Tellegen, C. (2012). Resilience in developmental psychopathology: Contributions of the Project Competence Longitudinal Study. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941200003X

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976

- Schwartz, C., Meisenhelder, J. B., Ma, Y., & Reed, G. (2003). Altruistic social interest behaviors are associated with better mental health. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(5), 778–785. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000079378.39062.d4

- Werner, E. E., & Smith, R. S. (2001). Journeys from childhood to midlife: Risk, resilience, and recovery. Cornell University Press.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1016

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College