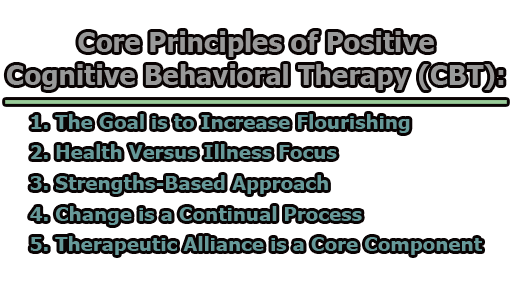

Core Principles of Positive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT):

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has long been recognized as an effective method for treating a range of psychological disorders by addressing dysfunctional emotions, behaviors, and thought patterns. However, traditional CBT has been critiqued for focusing primarily on symptom reduction and pathology. In response, Positive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) emerged as a modern, strengths-based adaptation, integrating concepts from positive psychology and solution-focused brief therapy. Rather than centering on what is wrong, Positive CBT emphasizes human strengths, well-being, and the pursuit of flourishing. It is grounded in the belief that people are not just looking to survive but to thrive (Bannink, 2012). The following are five core principles of Positive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT):

1. The Goal is to Increase Flourishing: One of the central tenets of Positive CBT is the shift in therapeutic goals from merely reducing symptoms to actively increasing flourishing. Flourishing, as defined in positive psychology, refers to living a life rich in meaning, engagement, and positive emotion (Seligman, 2011). Rather than focusing on alleviating distress alone, Positive CBT seeks to promote psychological well-being by helping individuals build on their strengths, enhance their emotional health, and foster satisfying relationships and life accomplishments.

A foundational model supporting this approach is Seligman’s PERMA model, which identifies five key elements of well-being:

- Positive Emotion (experiencing joy, gratitude, hope)

- Engagement (being deeply involved in activities)

- Relationships (having supportive and meaningful social connections)

- Meaning (having a sense of purpose)

- Accomplishment (working toward and achieving goals) (Seligman, 2011).

Positive CBT incorporates interventions that stimulate these dimensions. For instance, clients may engage in activities designed to boost gratitude or recognize meaningful moments in their lives. A common practice includes reframing negative thoughts into constructive or balanced perspectives, promoting a more optimistic and empowering view of the world (Bannink, 2012).

Another critical aspect of this principle is the positivity ratio, a concept introduced by Fredrickson and Losada (2005), which suggests that people flourish when they experience at least three positive emotions for every negative one (3:1 ratio). This ratio was found to correlate with enhanced creativity, resilience, and overall functioning. Fowler and Christakis (2008) also demonstrated that positive emotions spread through social networks, suggesting that individual well-being can contribute to broader societal benefits. Hence, increasing flourishing is not only beneficial on a personal level but also contributes to the collective well-being of families, workplaces, and communities.

By focusing on increasing what is good in life, Positive CBT offers clients a proactive and hopeful framework, supporting the development of a life that is not just functional, but rich, meaningful, and joyful.

2. Health Versus Illness Focus: Traditional CBT approaches often begin with identifying psychological symptoms or maladaptive behaviors—essentially, focusing on what is wrong. In contrast, Positive CBT emphasizes what is right and what is possible. This principle encourages a health-focused orientation, wherein therapy is structured around enhancing wellness rather than just reducing pathology (Bannink, 2012).

In Positive CBT, clients are encouraged to set goals not based on what they want to stop (e.g., “I want to stop being anxious”) but on what they want to move toward (e.g., “I want to feel more confident in social situations”). This subtle but powerful shift transforms the therapeutic dialogue from one of deficit and dysfunction to one of potential and growth. The focus becomes constructive goal-setting, where the client, not the therapist, defines what success looks like.

An essential tool used in this approach is future envisioning. Clients are invited to describe in detail what their lives will look like when their goals are achieved. This helps clarify values, activate hope, and strengthen motivation. The therapist’s role is not to diagnose or correct but to facilitate a conversation that brings out the client’s own aspirations, abilities, and desired outcomes (Bannink, 2012).

Moreover, this principle aligns with the solution-focused brief therapy perspective, which holds that solutions and progress do not necessarily come from understanding problems but from identifying exceptions, successes, and pathways forward (de Shazer et al., 2021). By focusing on desired futures and what already works, clients can tap into intrinsic motivation and existing capabilities.

Ultimately, by prioritizing health and wellness over illness and deficits, Positive CBT creates a more empowering therapeutic environment—one that inspires clients to build on their potential and take ownership of their healing and personal development.

3. Strengths-Based Approach: One of the defining features of Positive CBT is its strengths-based orientation, which stems from the foundational principles of positive psychology. Unlike traditional therapeutic approaches that concentrate on deficits or disorders, Positive CBT actively explores and builds upon the client’s existing strengths and inner resources (Bannink, 2012). The assumption is that all individuals possess unique character strengths and abilities that can be harnessed to navigate life’s challenges and achieve personal goals.

To identify these qualities, therapists often use empirically validated tools such as the Values in Action (VIA) Inventory of Strengths. Developed by Peterson and Seligman (2004), this assessment categorizes 24 character strengths under six broad virtues: wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. Examples of character strengths include creativity, perseverance, kindness, gratitude, and hope. Once identified, these strengths can be intentionally applied to help clients tackle specific problems or pursue meaningful goals.

For instance, a client experiencing social anxiety might discover that one of their signature strengths is “kindness.” The therapist might encourage the client to express this strength in small social interactions, thereby shifting the focus from anxiety to positive action that reinforces confidence and social connection.

In addition to structured assessments, therapists also use narrative techniques to highlight strengths. This might involve asking clients to recall times when they overcame difficulties, acted bravely, or achieved something important. By reflecting on past successes, clients begin to view themselves as capable and resilient rather than broken or weak.

This strengths-based mindset contributes significantly to self-efficacy—the belief in one’s own ability to manage and succeed. According to Peterson (2006), cultivating such strengths not only helps resolve present issues but also supports sustained well-being over time. By focusing on what is right with the client, rather than what is wrong, Positive CBT offers a more hopeful and empowering pathway to psychological growth.

4. Change is a Continual Process: In Positive CBT, change is not seen as a one-time breakthrough but as a continuous, evolving process. This principle acknowledges that personal growth and healing unfold over time through a series of small, meaningful steps (Bannink, 2012). Rather than waiting for dramatic transformations, Positive CBT emphasizes the importance of recognizing and celebrating small wins, which can significantly boost a client’s confidence and motivation.

This principle is aligned with solution-focused brief therapy, which encourages clients to pay attention to “exceptions” to their problems—that is, times when things were slightly better or more manageable. Identifying these moments can help clients uncover effective strategies they have already used and replicate them in future situations (de Shazer et al., 2021). Every small act of progress is treated as evidence that positive change is already happening.

Moreover, the process of ongoing change is supported by developing what Carol Dweck (2006) refers to as a “growth mindset”—the belief that abilities and intelligence can be developed with effort, learning, and persistence. Clients are encouraged to view setbacks not as failures, but as part of a longer journey of development. This perspective reduces the fear of failure and increases resilience, as clients come to understand that difficulties are opportunities for learning and growth.

Therapists play an important role in reinforcing this principle by regularly asking clients questions such as:

- “What’s better since our last session?”

- “What small step did you take toward your goal this week?”

- “What did you learn about yourself recently?”

These inquiries highlight progress and create an upward momentum. Over time, this builds a sense of mastery and encourages clients to take further steps, ultimately leading to lasting, self-directed change.

5. Therapeutic Alliance is a Core Component: A strong and trusting therapeutic alliance is fundamental to the effectiveness of any psychotherapy, and in Positive CBT, it holds even greater significance. This approach views the therapist-client relationship not merely as a foundation for treatment but as an active and dynamic force that shapes the entire healing process (Bannink, 2012). Positive CBT emphasizes a collaborative partnership, where both therapist and client work together toward clearly defined goals in an atmosphere of mutual respect, empathy, and empowerment.

From the very first session, Positive CBT focuses on building rapport and creating a safe, nonjudgmental space where the client feels valued and understood. The therapist adopts a coaching stance rather than an authoritative or directive role, inviting the client to be an equal partner in the therapeutic journey. This client-centered approach increases engagement and motivation, making clients more likely to commit to the therapeutic process and apply learned skills outside of sessions (Norcross & Wampold, 2011).

An important aspect of the therapeutic alliance in Positive CBT is the respect for client autonomy. The therapist supports the client in setting their own goals, choosing interventions that resonate with them, and evaluating progress. This reinforces the idea that clients are the experts of their own lives and fully capable of directing their personal growth. According to Bannink (2012), giving clients this sense of control strengthens their sense of agency and promotes a more active and hopeful engagement with change.

Additionally, Positive CBT encourages the co-creation of meaning within the therapeutic dialogue. Rather than interpreting or analyzing problems on behalf of the client, the therapist asks solution-focused and positively framed questions like:

- “What is already working for you?”

- “How will you know when things are better?”

- “What would a good day look like for you?”

These types of questions empower clients to reflect on their own capabilities, preferences, and values. They also help maintain a forward-looking focus, directing attention toward what the client wants to achieve rather than what they want to avoid.

Research consistently affirms that the strength of the therapeutic alliance is a key predictor of positive treatment outcomes across all types of therapy (Norcross & Wampold, 2011). In Positive CBT, this alliance is not just a helpful addition—it is a core mechanism of change, fostering hope, engagement, and long-term well-being.

It is apparent that Positive CBT represents a significant evolution in psychotherapy, integrating the rigor of cognitive behavioral techniques with the empowering principles of positive psychology. Its focus on flourishing, strengths, self-defined goals, ongoing change, and therapeutic collaboration makes it especially effective for clients seeking more than symptom relief. By promoting positive emotions and leveraging what is strong rather than what is wrong, Positive CBT fosters a proactive and hopeful pathway to mental well-being. As Bannink (2012) emphasized, the ultimate goal is not merely to treat dysfunction but to build lives worth living—full of meaning, joy, and resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is Positive CBT?

Positive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or Positive CBT, is a modern approach to psychological therapy that combines traditional cognitive behavioral strategies with the uplifting and empowering focus of positive psychology. Rather than simply reducing negative symptoms like anxiety or depression, Positive CBT aims to help individuals build happiness, well-being, resilience, and a greater sense of purpose in life. It encourages people to focus on their strengths, positive emotions, and what is already going well, while still addressing challenges in a constructive way.

How is Positive CBT different from traditional CBT?

Traditional CBT mainly concentrates on identifying and changing negative thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors that contribute to emotional distress. While it’s highly effective, it often places more emphasis on fixing what’s wrong. Positive CBT takes this a step further by also focusing on what’s right—helping clients to notice their strengths, appreciate positive experiences, and move toward meaningful goals. It doesn’t ignore problems, but it invites a more hopeful, forward-looking, and solution-based mindset. It asks not just, “What do you want to stop?” but “What kind of life do you want to create?”

Who is Positive CBT suitable for?

Positive CBT is well-suited for a wide variety of people. It can help those struggling with mild to moderate emotional challenges such as stress, anxiety, or low mood. It is also ideal for individuals who are functioning well but want to improve their life satisfaction, build confidence, or gain clarity about their goals. Since the approach is empowering and focused on personal strengths, many clients find it motivating and uplifting. It’s also useful in coaching and workplace settings where growth and development are key goals.

Does Positive CBT ignore negative thoughts or difficult emotions?

Not at all. Positive CBT recognizes the reality of negative emotions, struggles, and painful experiences. However, instead of dwelling on these difficulties, it helps individuals understand them in context and find ways to move forward. The emphasis is on balancing challenges with hope, noticing what is still possible, and drawing strength from past successes. Negative thoughts are still addressed—but they are reframed in a more empowering light, helping clients regain control and optimism.

What role does the therapist play in Positive CBT?

In Positive CBT, the therapist acts as a collaborative guide or coach rather than a problem-solver or expert. The client is seen as the expert on their own life, and the therapist’s job is to support and amplify their natural strengths, insights, and motivation. Together, they explore what is already working, define what success looks like, and build a plan for achieving it. The relationship between therapist and client is based on trust, encouragement, and mutual respect, which is crucial for the success of the therapy.

What techniques are used in Positive CBT?

Positive CBT uses a wide variety of techniques that draw from both cognitive behavioral therapy and positive psychology. Some of these include:

- Reframing negative thoughts to highlight growth, learning, or opportunity

- Identifying personal strengths and learning how to apply them in everyday life

- Setting positive, meaningful goals rather than only focusing on symptom relief

- Practicing gratitude and appreciation to enhance emotional well-being

- Savoring positive moments, even small ones, to build a sense of joy and presence

- Visualizing a preferred future to inspire action and motivation

- Solution-focused questioning to uncover past successes and inner resources

These strategies help individuals shift from surviving to thriving.

Is Positive CBT effective?

Yes, many people find Positive CBT to be highly effective, especially those who are looking for a more uplifting and motivational therapy experience. It supports emotional healing while also encouraging personal growth, goal setting, and self-discovery. Because it focuses on what works and builds momentum through small successes, clients often report feeling more hopeful, capable, and empowered early in the process.

Can children or teenagers benefit from Positive CBT?

Absolutely. Positive CBT can be adapted for children and adolescents, especially because it emphasizes strengths, values, and positive experiences—areas that can be very engaging for younger people. When therapy is fun, interactive, and focused on what the child or teen does well, they are more likely to feel comfortable and participate actively. Parents or guardians can also be included to help reinforce progress at home.

How long does Positive CBT take to work?

Positive CBT is typically designed to be brief and goal-oriented. Some individuals begin to notice improvements within just a few sessions, especially when they are actively engaged and apply the techniques in daily life. While therapy duration can vary depending on each person’s needs, many people see meaningful progress in 6 to 12 sessions. Of course, some may choose to continue for longer periods for deeper exploration and development.

What kinds of goals can someone work on in Positive CBT?

The goals in Positive CBT are personal and client-defined. Some people work on improving their emotional resilience or managing stress, while others focus on building stronger relationships, finding meaning in their work, or boosting self-confidence. Others may want to overcome procrastination, develop healthier habits, or explore a more fulfilling life direction. The common thread is that the goals are positive, realistic, and meaningful—focused not on avoiding problems but on creating a life that feels rewarding and purposeful.

References:

- Bannink, F. (2012). Practicing positive CBT: From reducing distress to building success. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House Publishing Group.

- De Shazer, S., Dolan, Y., Korman, H., Trepper, T., McCollum, E. and Berg, I.K. (2021) More than Miracles the State of the Art of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy. Routledge, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003125600

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Losada, M. F. (2005). Positive Affect and the Complex Dynamics of Human Flourishing. American Psychologist, 60(7), 678–686. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678

- Fowler, J.H. and Christakis, N.A. (2008) Dynamic Spread of Happiness in a Large Social Network: Longitudinal Analysis over 20 Years in the Framingham Heart Study. British Medical Journal, 337, 1-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a2338

- Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2011). Evidence-based therapy relationships: Research conclusions and clinical practices. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022161

- Peterson, C. (2006). The Values in Action (VIA) Classification of Strengths: The un-DSM and the real DSM. In M. Csikszentmihalyi & I. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), A life worth living: Contributions to positive psychology (pp. 29–48). Oxford University Press.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press; American Psychological Association.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College