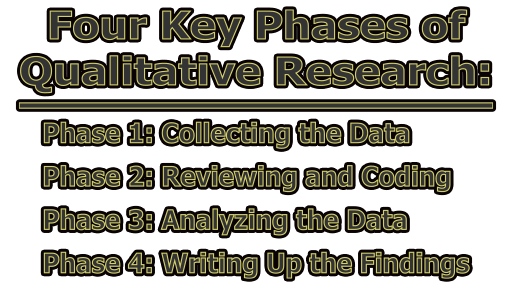

Four Key Phases of Qualitative Research:

Qualitative research is a powerful approach for exploring human experiences, social interactions, and complex phenomena in depth. However, for researchers new to this methodology, the process can seem daunting. To provide clarity, this article outlines the four key phases of qualitative research: data collection, reviewing and coding, data analysis, and writing up the findings.

Phase 1: Collecting the Data:

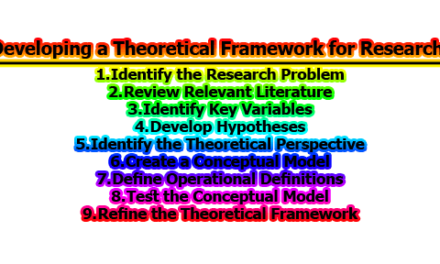

The foundation of qualitative research lies in the data collection phase. The richness and depth of the data directly influence the validity and impact of the study. As Flick (2018) notes, the choice of data collection methods should align with the research question and design to ensure meaningful and relevant insights.

Common Data Collection Methods:

i. Interviews: One-on-one interviews allow researchers to explore participants’ perspectives, experiences, and emotions in detail. Open-ended questions foster a deep understanding of the subject matter (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2015).

- Structured Interviews: A predefined set of questions ensures consistency across participants.

- Semi-Structured Interviews: A mix of fixed and flexible questions allows for deeper exploration.

- Unstructured Interviews: Conversations flow naturally, uncovering unexpected insights.

Researchers should establish rapport with participants to encourage honest responses, ensuring ethical considerations such as informed consent and confidentiality are upheld (Seidman, 2019).

ii. Observations: This method involves directly witnessing and recording behaviors in their natural settings. Ethnographic studies often rely on observations to uncover nuanced social interactions (Angrosino, 2007).

- Participant Observation: The researcher immerses themselves in the environment while actively engaging with participants.

- Non-Participant Observation: The researcher remains a passive observer to minimize influence on the setting.

- Field Notes and Audio-Visual Recording: Detailed documentation enhances data reliability and allows for richer analysis (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 2011).

iii. Documents and Archival Research: Analyzing written materials such as letters, reports, or journals provides insights into historical contexts, organizational structures, and personal narratives (Bowen, 2009).

- Primary Documents: Created at the time of an event, such as official records, letters, or diaries.

- Secondary Documents: Analyzed or interpreted records, such as literature reviews or media reports.

- Digital Archival Research: Online resources and databases serve as valuable repositories for qualitative data.

iv. Fieldwork: Immersing oneself in the research setting helps gather first-hand experiences, fostering a deeper contextual understanding (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 2011).

- Extended Engagement: Spending prolonged time in the field enhances understanding of the cultural or social dynamics.

- Building Trust with Participants: Essential for eliciting authentic responses and reducing observer bias.

- Ethical Considerations: Ensuring anonymity and consent is crucial in sensitive environments (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

Best Practices for Data Collection:

- Intentionality: Align data collection methods with the research objectives (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

- Quality over Quantity: Prioritize depth and richness over sheer volume (Mason, 2010).

- Building Trust: Establish rapport with participants to encourage honesty and openness (Seidman, 2019).

- Reflexivity: Researchers should remain aware of their biases and how these may impact the data collection process (Berger, 2015).

By following these best practices, researchers can ensure that their data collection methods yield meaningful and reliable results, setting a strong foundation for the subsequent phases of qualitative research.

Phase 2: Reviewing and Coding:

Once data has been collected, the next crucial step in qualitative research is reviewing and coding. This phase transforms raw data into structured, meaningful segments that pave the way for analysis. As Saldaña (2021) states, qualitative coding is an iterative process that helps researchers identify themes, patterns, and relationships within the dataset.

Understanding Qualitative Coding: Qualitative coding is the process of assigning labels (codes) to segments of data that represent specific ideas, themes, or categories. This systematic approach allows researchers to organize and interpret data effectively (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2018).

- Inductive Coding: Emerging codes are developed based on patterns observed in the data without predefined categories (Thomas, 2006).

- Deductive Coding: Codes are based on an existing theoretical framework or prior research (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

- Hybrid Coding: A combination of inductive and deductive approaches, allowing flexibility in analysis (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006).

Steps in the Coding Process:

i. Data Familiarization:

- Read through transcripts, field notes, or documents multiple times to develop a comprehensive understanding.

- Take preliminary notes highlighting recurring words, phrases, or patterns (Nowell et al., 2017).

ii. Developing a Coding Framework:

- Define codes based on key concepts in the research question and literature review.

- Ensure codes are clear, mutually exclusive, and comprehensive to avoid overlap (Boyatzis, 1998).

iii. Applying Codes to Data:

- Use software such as NVivo, Atlas.ti, or manual methods like color-coding and spreadsheets.

- Assign labels to text segments that fit the coding framework, refining categories as needed (Gibbs, 2018).

iv. Identifying Themes and Patterns:

- Group similar codes into broader themes that represent significant insights.

- Use visual tools like coding trees or matrices to examine relationships between themes (Clarke & Braun, 2017).

v. Ensuring Reliability and Validity:

- Inter-Coder Reliability: Have multiple researchers code the same data and compare results to ensure consistency (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020).

- Reflexivity: Researchers should document their thoughts and biases throughout the coding process to maintain transparency (Berger, 2015).

- Audit Trails: Keeping a record of coding decisions and changes enhances credibility (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Practical Example: Imagine conducting interviews on workplace stress. During the coding process, you notice recurring mentions of “workload pressure,” “lack of support,” and “burnout.” You assign these phrases to corresponding codes and later identify overarching themes like “organizational challenges” and “employee well-being.”

Best Practices for Reviewing and Coding:

- Remain Flexible: Adjust codes as new insights emerge (Saldaña, 2021).

- Use Software When Possible: Digital tools streamline coding and reduce errors (Silver & Lewins, 2014).

- Seek Feedback: Discuss coding frameworks with colleagues or advisors to refine interpretations (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

By following a structured coding approach, researchers can systematically organize qualitative data, ensuring that themes and patterns emerge in a meaningful and reliable manner. This phase is foundational for the subsequent data analysis stage, where deeper interpretations are made.

Phase 3: Analyzing the Data:

Once qualitative data has been reviewed and coded, the next essential step is analysis. This phase involves interpreting patterns, themes, and relationships within the coded data to extract meaningful insights. According to Braun and Clarke (2006), qualitative data analysis is an iterative process that requires deep engagement with the data to uncover underlying meanings and connections.

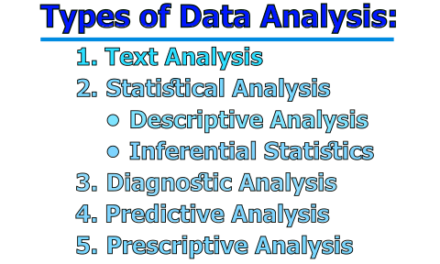

Approaches to Qualitative Data Analysis: There are multiple approaches to analyzing qualitative data, each suitable for different research objectives:

i. Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006):

- Focuses on identifying, analyzing, and reporting themes within the data.

- Useful for exploring participants’ experiences, perceptions, and emotions.

- Steps:

- Familiarization with data (re-reading, noting initial thoughts).

- Generating initial codes (applying labels to meaningful text segments).

- Searching for themes (grouping codes into broader categories).

- Reviewing themes (refining and ensuring coherence among themes).

- Defining and naming themes (clarifying meanings and relationships).

- Producing the final report (presenting findings with supporting evidence).

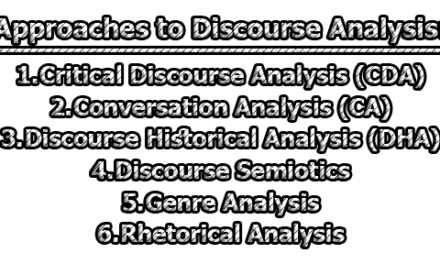

ii. Discourse Analysis (Gee, 2014):

- Examines language use, social structures, and power relations.

- Analyzes how communication constructs meaning within specific contexts.

- Useful for studying ideologies, cultural narratives, and institutional discourse.

iii. Narrative Analysis (Riessman, 2008):

- Focuses on how individuals construct meaning through storytelling.

- Examines personal experiences, autobiographies, or life histories.

- Useful for understanding identity formation, social interactions, and subjective interpretations.

iv. Content Analysis (Krippendorff, 2018):

- Systematically categorizes textual data based on the frequency of certain words, concepts, or themes.

- Bridges qualitative and quantitative research by providing structured analysis.

- Useful for analyzing media content, policy documents, and historical records.

Steps in Data Analysis:

a. Data Immersion:

- Researchers should deeply engage with the data, continuously reflecting on patterns and potential meanings (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

- Memo-writing can be useful to capture thoughts and analytical ideas (Charmaz, 2014).

b. Pattern Recognition and Theme Development:

- Themes should emerge naturally from the data, with careful validation to ensure they align with research questions (Nowell et al., 2017).

- Using software like NVivo or MAXQDA can facilitate pattern detection and visualization.

c. Linking Findings to Theory:

- Themes should be connected to existing theories or frameworks to enhance interpretative depth (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

- This process ensures that findings contribute meaningfully to academic discussions.

d. Triangulation for Validity:

- Comparing multiple data sources (e.g., interviews, observations, and documents) strengthens the credibility of findings (Patton, 1999).

- Peer debriefing and member checking (seeking participant validation) enhance reliability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Practical Example: For a study on remote work challenges, a thematic analysis might reveal key themes such as “lack of work-life boundaries,” “technological stress,” and “team communication gaps.” These insights help researchers understand common struggles and propose organizational solutions.

Best Practices for Data Analysis:

- Remain Open to Emerging Insights: Data analysis should be flexible, allowing new themes to surface (Saldaña, 2021).

- Use Visualization Tools: Concept maps, thematic matrices, and coding trees aid in organizing findings (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2018).

- Justify Interpretations with Evidence: Use direct quotes, excerpts, and case examples to support conclusions (Creswell, 2013).

By carefully analyzing qualitative data, researchers can derive valuable insights that inform broader academic and practical discussions. This phase sets the foundation for the final step—writing up the findings in a coherent and compelling manner.

Phase 4: Writing Up the Findings:

The final phase of qualitative research is writing up the findings, where researchers present their analysis in a structured, coherent, and engaging manner. This stage is crucial as it transforms raw data and insights into a scholarly narrative that contributes to academic and practical knowledge (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Structuring the Write-Up: A well-organized report ensures clarity, coherence, and credibility. Typically, a qualitative research write-up includes the following sections:

i. Introduction:

- Provides a brief overview of the research problem, objectives, and significance.

- Outlines the research questions and methodological approach (Silverman, 2020).

ii. Methodology:

- Describes data collection methods, participant selection, and ethical considerations.

- Justifies the chosen analytical framework (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

iii. Findings and Analysis:

- Presents key themes and patterns that emerged from the data.

- Supports claims with direct quotes, excerpts, and case examples (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

- Uses visual tools like thematic maps, coding trees, or diagrams to enhance comprehension (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2018).

iv. Discussion:

- Interprets findings in relation to existing literature and theoretical frameworks.

- Highlights unexpected insights and their implications (Patton, 1999).

- Acknowledges study limitations and suggests areas for future research (Creswell, 2013).

v. Conclusion:

- Summarizes key takeaways and contributions to knowledge.

- Suggests practical applications of the findings (Nowell et al., 2017).

Best Practices for Writing Up Qualitative Research:

a. Tell a Compelling Story:

- Findings should be presented as a cohesive narrative, connecting themes and insights logically (Riessman, 2008).

- Use storytelling techniques to illustrate real-world implications of the data.

b. Use Participants’ Voices:

- Incorporate verbatim quotes to maintain authenticity and provide evidence for claims (Gibbs, 2018).

- Ensure anonymity and confidentiality by using pseudonyms where necessary (Berger, 2015).

c. Maintain Transparency and Reflexivity:

- Clearly describe the researcher’s role and potential biases in interpreting findings (Charmaz, 2014).

- Document decision-making processes to enhance credibility (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

d. Ensure Coherence and Consistency:

- Findings should directly answer the research questions and align with the coding and analytical framework (Silver & Lewins, 2014).

- Avoid unnecessary repetition and ensure logical flow across sections.

e. Engage with the Literature:

- Compare findings with existing studies to highlight contributions to the field (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

- Discuss whether results confirm, challenge, or extend prior research (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

Practical Example: For a study on work-life balance, the findings section might discuss themes such as “flexibility as a double-edged sword” or “stress management strategies.” The discussion would then interpret these insights in relation to theories of organizational behavior and workplace well-being.

So, writing up qualitative findings is not just about reporting data but crafting an insightful and impactful narrative. By maintaining clarity, coherence, and engagement, researchers ensure that their findings contribute meaningfully to academic discourse and practical applications.

The Iterative Nature of Qualitative Research:

Qualitative research is rarely a linear process; instead, it follows an iterative cycle where data collection, analysis, and interpretation often overlap. This iterative nature allows researchers to refine their understanding and adapt their approaches as new insights emerge (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Characteristics of Iteration in Qualitative Research:

i. Continuous Refinement of Research Questions:

- As researchers immerse themselves in the data, initial research questions may evolve to better capture emerging patterns and themes (Maxwell, 2013).

- This flexibility enables a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the research topic (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

ii. Revisiting Data Collection:

- If gaps or inconsistencies arise during analysis, researchers may return to the field to collect additional data (Charmaz, 2014).

- This process ensures a more comprehensive dataset and enhances the study’s validity (Silverman, 2020).

iii. Ongoing Data Coding and Re-Coding:

- Initial codes may be revised or expanded as deeper insights develop (Saldaña, 2021).

- Iterative coding helps to refine categories and uncover latent meanings in the data (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2018).

iv. Emergent Themes and Theory Development:

- Rather than imposing pre-existing frameworks, qualitative research often allows themes to emerge naturally (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

- The constant comparison method helps to refine concepts and build theories grounded in the data (Corbin & Strauss, 2015).

Practical Implications of an Iterative Approach:

- Enhancing Data Validity: Returning to participants for clarification (member checking) strengthens credibility (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

- Increasing Analytical Rigor: The iterative review of findings ensures thorough and well-supported interpretations (Nowell et al., 2017).

- Encouraging Reflexivity: Researchers continuously reflect on their positionality and its impact on data interpretation (Berger, 2015).

Example of Iteration in Practice: In a study on remote work dynamics, initial interviews may highlight “work-life balance” as a major theme. Further interviews or observations might reveal nuanced perspectives, such as differences based on job roles or organizational culture. This feedback loop allows researchers to refine their questions and deepen their analysis.

Thus, embracing iteration in qualitative research strengthens the depth and credibility of findings. By continuously revisiting data collection, coding, and analysis, researchers remain open to new interpretations and ensure their work is both robust and insightful.

Key Takeaways:

- Data collection involves gathering rich, meaningful insights through interviews, observations, and documents.

- Reviewing and coding structures data into themes, facilitating analysis.

- Data analysis employs methods such as thematic, discourse, narrative, and content analysis to derive insights.

- Writing up synthesizes findings into a compelling academic narrative.

By embracing the iterative nature of qualitative research, scholars can produce robust, insightful, and impactful studies that contribute meaningfully to their fields (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a method of inquiry that focuses on understanding human experiences, behaviors, and social phenomena through non-numerical data such as interviews, observations, and textual analysis.

How does qualitative research differ from quantitative research?

Qualitative research explores in-depth perspectives and meanings, while quantitative research focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis to test hypotheses.

What are common qualitative research methods?

Common methods include interviews, focus groups, observations, document analysis, and ethnography.

How is data collected in qualitative research?

Data is typically collected through direct interaction with participants, written documents, and field observations. Methods vary depending on the research design and objectives.

What is coding in qualitative research?

Coding involves categorizing and labeling qualitative data to identify patterns, themes, and relationships within the dataset.

What are the key phases of qualitative research?

The key phases include data collection, reviewing and coding, analyzing the data, and writing up the findings.

What is thematic analysis?

Thematic analysis is a method used to identify, analyze, and interpret patterns (themes) within qualitative data.

How do researchers ensure the credibility of qualitative research?

Credibility is maintained through techniques like triangulation, member checking, reflexivity, and audit trails.

Why is qualitative research considered iterative?

Qualitative research is iterative because researchers often revisit data collection, coding, and analysis multiple times to refine their insights and ensure a comprehensive understanding.

What are some challenges in qualitative research?

Challenges include subjectivity, time-consuming data collection and analysis, difficulty in generalizing findings, and ensuring researcher reflexivity.

How is qualitative data presented in research findings?

Findings are typically presented using descriptive narratives, direct quotations, thematic discussions, and connections to existing literature.

Can qualitative and quantitative research be combined?

Yes, mixed-methods research integrates both qualitative and quantitative approaches to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a research problem.

What ethical considerations are important in qualitative research?

Key ethical considerations include informed consent, confidentiality, participant privacy, and minimizing researcher bias.

What software tools are used for qualitative data analysis?

Common software tools include NVivo, Atlas.ti, MAXQDA, and Dedoose, which help researchers manage, code, and analyze qualitative data.

How long does qualitative research typically take?

The duration varies depending on the study’s scope, complexity, and data collection methods, but it can range from several weeks to months or even years in extensive studies.

References:

- Angrosino, M. (2007). Doing Ethnographic and Observational Research. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208932

- Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9, 27-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic Analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12, 297-298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226206868.001.0001

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Flick, U. (2018). An Introduction to Qualitative Research (6th ed.). https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/an-introduction-to-qualitative-research/book261109

- Gee, J.P. (2014). An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. Routledge, Oxon.

- Gibbs, G. R. (2018). Analyzing qualitative data (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526441867

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Sage Publications.

- Kvale, S. and Brinkmann, S. (2015). Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 3rd Edition, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

- Mason, M. (2010). Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1428/3027

- Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2018). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

- Patton, M. Q. (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research, 34(5 Pt 2), 1189–1208.

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage Publications.

- Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Seidman, I. (2019). Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. Teachers College Press.

- Silver, C., & Lewins, A. (2014). Using software in qualitative research: A step-by-step guide (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473906907

- Silverman, D. (2020). Interpreting qualitative data (6th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College