How to Manage Eco-Anxiety With Positive Psychology:

Eco-anxiety is increasingly emerging as a significant psychological concern in the context of accelerating climate change. While concern for the environment has long existed, eco-anxiety goes beyond ordinary worry. It represents a deep emotional and cognitive response to the existential threat that climate change poses to personal safety, community stability, and humanity’s collective future. As Pihkala (2020) explains, eco-anxiety (also referred to as climate anxiety or climate distress) is not simply environmental concern, but a complex emotional reaction that may include fear, grief, guilt, anger, and helplessness. Recent research has further recognized eco-anxiety as a legitimate mental health issue rather than a passing trend. Boluda-Verdú et al. (2022) emphasize that climate-related distress reflects a rational response to real and measurable environmental threats, yet it can significantly affect emotional wellbeing, daily functioning, and long-term outlook. For many individuals, particularly young people and those closely connected to environmental issues, this distress can feel overwhelming and persistent. Living and working in regions known for their natural beauty often intensifies this experience. When individuals witness environmental degradation firsthand, the abstract concept of climate change becomes deeply personal. Clients, families, and communities in such areas may report heightened fear about the future, sadness over environmental loss, and uncertainty about what lies ahead. Given the growing prevalence of eco-anxiety, mental health professionals are increasingly called upon to understand and address this form of climate-related distress. This article explores how to manage eco-anxiety with positive psychology.

What Is Eco-Anxiety?

Eco-anxiety is commonly described as a persistent or recurring fear of environmental catastrophe. Usher et al. (2019) characterize it as a “relentless fear of environmental doom,” often triggered by direct exposure to climate-related disasters, repeated engagement with scientific reports, or continual media coverage of environmental decline. Unlike fleeting concern, eco-anxiety tends to be sustained and emotionally charged, reflecting the magnitude and urgency of the climate crisis.

From a psychological standpoint, eco-anxiety sits at the intersection of several domains. It draws from environmental psychology, which studies human relationships with the natural world; climate change psychology, which explores emotional and behavioral responses to environmental threats; existential anxiety, which relates to fears about survival and meaning; and anticipatory grief, the mourning of expected future losses (Ágoston et al., 2022). This blend makes eco-anxiety a complex emotional phenomenon rather than a single, simple fear response.

Although eco-anxiety has not been formally classified as a mental disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), mental health professionals increasingly acknowledge it as a serious and legitimate form of psychological distress (Cosh et al., 2024). Importantly, its recognition does not imply pathology in the traditional sense. Instead, it reflects the understanding that distress related to climate change can significantly impact wellbeing, daily functioning, and long-term outlook.

A central psychological mechanism underlying eco-anxiety is the perceived imbalance between the scale of the environmental threat and an individual’s perceived capacity to influence it (Pihkala, 2020). When clients feel that climate change is vast, global, and accelerating; while their personal actions seem small or insufficient; this disparity can generate intense feelings of helplessness and loss of control. Such powerlessness may evolve into eco-guilt, a sense of personal responsibility for environmental harm, even when individual contributions are minor (Ágoston et al., 2022).

Additionally, eco-anxiety is often intertwined with anticipatory grief; the mourning of environmental losses that have not yet occurred but appear inevitable. Clients may grieve disappearing ecosystems, endangered species, or the anticipated degradation of landscapes that hold personal or cultural meaning. This anticipatory element makes eco-anxiety forward-looking, anchored not only in present realities but also in feared futures.

How Is Eco-Anxiety Different From General Anxiety?

Eco-anxiety shares several symptoms with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), including restlessness, persistent worry, sleep disturbance, and difficulty concentrating (Hogg et al., 2021). However, the distinction lies primarily in its source, context, and moral dimensions.

- Source of Distress: While GAD typically involves excessive worry across multiple life domains (such as health, finances, relationships, or work) eco-anxiety is specifically rooted in environmental and climate-related concerns (Pihkala, 2020). These concerns are often supported by scientific evidence and observable environmental changes, making them grounded in real-world phenomena rather than disproportionate or unrealistic fears.

- Time Frame: Eco-anxiety is frequently both present- and future-oriented. Individuals may worry about immediate environmental impacts, such as extreme weather events, while simultaneously fearing long-term consequences for future generations (Orrù et al., 2024). This extended temporal focus distinguishes eco-anxiety from many forms of generalized anxiety, which may revolve around more immediate or personal concerns.

- Moral and Existential Elements: Unlike GAD, eco-anxiety often contains a strong moral or ethical dimension. Individuals may experience distress linked to humanity’s collective responsibility for environmental degradation or their own perceived complicity in unsustainable practices (Banwell & Eggert, 2023). The anxiety is therefore not only about safety but also about identity, values, and responsibility.

In short, eco-anxiety differs from GAD in its environmental focus, future orientation, and moral depth. It is not an irrational fear but a psychologically meaningful response to a documented and pressing global challenge.

What Is the Difference Between Eco-Anxiety and Climate Grief?

Although eco-anxiety and climate grief are closely related, they differ in their emotional foundation (Pihkala, 2022). Eco-anxiety is primarily characterized by fear, uncertainty, and apprehension about environmental degradation and climate instability (Hogg et al., 2021). It is forward-looking and anticipatory.

Climate grief, by contrast, centers on sadness and mourning in response to ecological losses that have already occurred. Cunsolo and Ellis (2018) describe climate grief as the emotional response to the loss of species, landscapes, livelihoods, and cultural identities deeply tied to the natural world. It reflects the sorrow of witnessing tangible environmental change.

In practice, these experiences often overlap. Clients may simultaneously fear future destruction (eco-anxiety) while mourning present losses (climate grief). Anticipatory grief can further blur the boundaries, as individuals grieve losses they expect but have not yet experienced. Recognizing these nuanced differences allows mental health professionals to respond more precisely to clients’ emotional needs.

Who Experiences Eco-Anxiety Most?

Eco-anxiety can affect individuals across age groups, professions, and cultural backgrounds. However, research suggests that certain populations are more vulnerable (Boluda-Verdú et al., 2022).

- Women: Binary survey data indicate that women often report higher levels of eco-anxiety than men (Niedzwiedz & Katikireddi, 2023). This disparity may relate to gendered socialization patterns, caregiving roles, or heightened emotional attunement to relational and environmental concerns.

- Adolescents and Young Adults: Adolescents and young adults consistently show elevated rates of eco-anxiety (Hickman, 2020). Young people face the prospect of living through the long-term consequences of climate change, which may intensify feelings of uncertainty about education, careers, family life, and planetary stability. Their developmental stage (marked by identity formation and future planning) can amplify climate-related fears.

- Indigenous Peoples and Land-Connected Communities: Indigenous communities and groups whose cultural identities are deeply tied to land, water, and ecosystems (such as farmers) may experience heightened eco-anxiety (Coffey et al., 2021). For these communities, environmental degradation threatens not only physical survival but also cultural continuity, spiritual practices, and ancestral heritage.

- Scientists and Climate Activists: Individuals who work closely with climate data or are actively engaged in environmental advocacy are also at risk. Scientists and activists frequently exposed to alarming climate projections may experience significant distress, sometimes leading to burnout (Jarrett et al., 2024). Constant engagement with climate realities can intensify emotional fatigue and moral burden.

In sum, eco-anxiety is a multifaceted psychological response rooted in real environmental threats. It differs from generalized anxiety through its environmental focus, moral dimensions, and future orientation, and it intersects with (but remains distinct from) climate grief. Understanding who is most affected enables mental health professionals to provide informed, compassionate, and context-sensitive support.

4 Reasons Eco-Anxiety Is on the Rise:

Eco-anxiety does not arise in a vacuum. It reflects broader political, ecological, and social realities surrounding climate change, which helps explain why it is becoming more visible in clinical practice (Kankawale & Niedzwiedz, 2023). As environmental threats intensify and public awareness increases, many individuals experience climate-related distress not merely as private worry, but as a rational emotional response to global instability. Below are four key drivers contributing to the rise of eco-anxiety.

- Increased Media and Social Media Coverage: The modern information environment plays a significant role in amplifying climate-related distress. Constant exposure to headlines about wildfires, floods, extreme heatwaves, pollution, and biodiversity loss can make environmental threats feel immediate, inescapable, and overwhelming. Shao and Yu (2023) note that repeated media consumption of climate disasters can heighten perceived risk and intensify emotional responses.

Social media, in particular, accelerates the spread of emotionally charged content. Graphic images, urgent messaging, and polarized debates can create a sense of crisis that feels continuous and personal. For clients who regularly consume climate news without structured coping strategies, this saturation may contribute to chronic stress and anticipatory fear.

- Scientific Reports and Climate Projections: Another major contributor to eco-anxiety is the growing body of scientific evidence detailing the severity of climate change. Reports highlighting rising global temperatures, increasing extreme weather events, biodiversity collapse, and long-term planetary risks can provoke deep concern. Pihkala (2020) explains that exposure to alarming climate projections often fuels anticipatory anxiety, especially when individuals contemplate the implications for future generations.

For climate-literate individuals, the emotional impact can be particularly intense. Understanding the data in depth may increase awareness of potential irreversible damage, which can evoke feelings of grief, fear, and urgency. Without supportive frameworks for constructive engagement, scientific awareness may inadvertently intensify distress rather than empower action.

- Personal Experience of Climate Events: Eco-anxiety becomes especially acute when individuals directly experience climate-related disasters. Communities that endure wildfires, droughts, intensified storms, flooding, rising sea levels, or declining agricultural yields often report profound psychological effects. Makeda (2024) emphasizes that lived experience of environmental disruption transforms climate change from an abstract concept into a personal and immediate threat.

In such contexts, eco-anxiety may intertwine with trauma responses. Repeated exposure to environmental instability can undermine a sense of safety and predictability, contributing to chronic vigilance, fear about the future, and diminished trust in long-term stability.

- Government Inaction or Perceived Inadequate Response: Political responses to climate change significantly influence public emotional wellbeing. When governments delay, minimize, or appear ineffective in addressing climate challenges, individuals may feel powerless and betrayed. Kankawale and Niedzwiedz (2023) highlight how perceived institutional inaction can intensify frustration, helplessness, and hopelessness.

This dynamic is particularly pronounced among young people and climate activists who advocate for systemic change. When their calls for action are met with political resistance or slow progress, their anxiety may deepen into moral distress or disillusionment.

Acknowledging these broader drivers during therapeutic conversations can validate clients’ experiences and reduce self-blame. Baudon and Jachens (2021) suggest that recognizing the legitimacy of climate-related fears can serve as a first step toward resilience-building and transforming anxiety into constructive engagement.

5 Risk Factors for Eco-Anxiety:

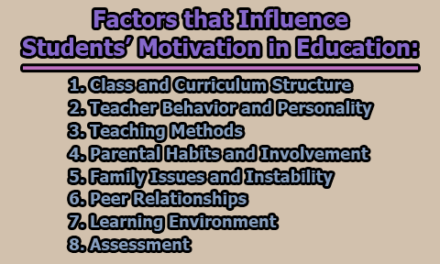

Eco-anxiety does not affect everyone equally. In clinical settings, clients may present with varying intensities and expressions of climate-related distress (Jalin et al., 2024). Personal history, social environment, emotional resilience, and physical context all shape vulnerability. Jarrett et al. (2024) emphasize that understanding these risk factors helps clinicians contextualize and normalize heightened anxiety. Below are five key risk factors that may increase susceptibility to eco-anxiety.

- Living in Climate-Sensitive Regions: Clients with a direct connection to climate-sensitive environments may experience environmental threats more acutely. Individuals in farming communities dependent on rainfall, coastal regions facing rising sea levels, or areas affected by overfishing or land degradation often perceive climate change as an immediate threat to livelihood and identity. Boyd et al. (2024) note that proximity to environmental risk heightens psychological vulnerability because the threat feels tangible and personal rather than distant.

- High Climate Literacy Without Coping Tools: Being well informed about climate science can be a double-edged sword. Sims et al. (2020) suggest that climate literacy may intensify eco-anxiety if individuals lack constructive coping strategies. When knowledge about environmental decline is not paired with opportunities for action, community engagement, or emotional processing, it may increase feelings of despair or helplessness.

- History of Trauma or Mental Health Challenges: Clients with prior trauma exposure or existing mental health conditions may be more susceptible to climate-related stress. Liu et al. (2025) indicate that preexisting vulnerabilities can amplify responses to environmental threats, potentially leading to overwhelming distress. Climate change may act as an additional stressor layered onto unresolved emotional challenges.

- High Media Immersion: Continuous engagement with disaster news and polarized climate debates can magnify fear and helplessness. Shao and Yu (2023) emphasize that excessive media consumption may reinforce perceptions of imminent catastrophe, contributing to chronic stress responses. Clients who lack boundaries around news intake may find their anxiety escalating over time.

- Social Isolation: Social support plays a crucial protective role in emotional regulation. Clients who lack supportive communities with whom they can share and validate climate concerns may experience compounded distress. Brophy et al. (2022) highlight that social isolation can intensify feelings of alienation and despair, particularly when individuals believe others do not take their environmental concerns seriously.

Understanding both the societal drivers and individual risk factors of eco-anxiety allows mental health professionals to respond with empathy and clarity. By contextualizing clients’ distress within real-world influences and personal vulnerabilities, clinicians can help reduce shame, validate emotional experiences, and guide individuals toward resilience-building strategies.

5 Psychological Symptoms Associated With Climate Anxiety:

Eco-anxiety does not present in a single, uniform way. Instead, it manifests across emotional, cognitive, and behavioral domains, with varying intensity depending on the individual. For some clients, climate anxiety may feel like a persistent background concern that surfaces occasionally. For others, it may escalate into a chronic and disruptive psychological state that interferes with sleep, concentration, relationships, and decision-making. Hogg et al. (2021) identify several core categories of psychological symptoms commonly associated with climate anxiety. Understanding these patterns allows clinicians to better assess, validate, and support affected individuals.

- Affective or Emotional Symptoms: At its core, eco-anxiety is deeply emotional. Clients frequently report feelings of fear, sadness, grief, anger, frustration, or helplessness in response to environmental degradation (Hogg et al., 2021). Fear may center on extreme weather events, biodiversity loss, food insecurity, or political inaction. Sadness and grief may arise from witnessing damaged ecosystems or anticipating irreversible loss.

These emotional responses are often layered and complex. For example, a client may simultaneously feel fear about the future, anger toward institutions, and guilt about personal consumption habits. Recognizing these emotional layers is essential, as they reflect meaningful engagement with real-world concerns rather than irrational distress.

- Rumination and Persistent Thoughts: Another common symptom category involves cognitive patterns, particularly rumination. Clients may experience repetitive, intrusive thoughts about climate change, ecological collapse, or worst-case future scenarios (Hogg et al., 2021). This persistent mental replaying of environmental threats can heighten anxiety and make it difficult to disengage from distressing content.

Rumination often intensifies when individuals consume large amounts of climate-related information or feel uncertain about solutions. Over time, these repetitive thought cycles may impair concentration, disrupt work or academic performance, and interfere with restorative downtime.

- Behavioral Changes and Avoidance: Eco-anxiety can also influence behavior. Some clients may significantly alter their daily habits in response to environmental concerns. While many changes (such as reducing waste or conserving energy) are adaptive and values-driven, others may become excessive or avoidance-based (Hogg et al., 2021).

For instance, clients might avoid traveling due to carbon footprint concerns, withdraw from conversations about climate issues because they feel overwhelmed, or disengage from long-term planning because the future feels uncertain. In more severe cases, eco-anxiety may contribute to social withdrawal or burnout, particularly among activists or environmentally conscious individuals.

- Anticipatory Anxiety About the Future: A defining feature of climate anxiety is its future orientation. Clients often experience anticipatory anxiety; worry about what may happen rather than what is currently occurring (Hogg et al., 2021). These fears may include concerns about extreme weather events, ecosystem collapse, resource scarcity, or geopolitical instability driven by environmental pressures.

Importantly, this anxiety frequently extends beyond personal safety. Many individuals express deep concern for their children, future generations, vulnerable communities, and the planet as a whole. This broad moral horizon distinguishes eco-anxiety from more self-focused forms of anxiety. The weight of imagining an uncertain or unstable future can feel emotionally exhausting and destabilizing.

- Eco-Guilt: Eco-guilt is another significant psychological symptom. Clients may feel personally responsible for contributing to environmental degradation through everyday behaviors such as travel, consumption, or energy use (Hogg et al., 2021). Even when individuals take meaningful pro-environmental actions, they may perceive their efforts as insufficient relative to the scale of the problem.

This sense of moral responsibility can intensify distress, particularly in individuals who hold strong environmental values. If left unaddressed, eco-guilt may lead to shame, self-criticism, or perfectionistic standards regarding sustainability.

Recognizing these emotional, cognitive, and behavioral symptom patterns allows clinicians to frame eco-anxiety as a coherent and understandable psychological response. Tingley (2023) emphasizes that normalizing these reactions (rather than pathologizing them) can help clients accept and acknowledge their distress. From this foundation of validation, individuals are better positioned to develop healthier coping strategies, cultivate resilience, and channel their concern into constructive action.

The Role of Hope in Managing Eco-Anxiety:

Historically, hope has sometimes been dismissed as naïve optimism or wishful thinking; an unrealistic attempt to soften harsh realities. However, contemporary psychological research suggests that hope is far more robust and transformative than mere positive thinking. Murphy (2023) describes hope as a powerful psychological resource that strengthens emotional endurance and supports adaptive coping in times of uncertainty. Rather than denying difficulty, hope allows individuals to face challenges with sustained motivation and meaning.

Within the field of positive psychology, hope has been consistently linked to improved emotional regulation, goal-directed behavior, and resilience. Ciarrochi et al. (2015) demonstrate that cultivating hope can help individuals manage distress more effectively, remain engaged in valued pursuits, and maintain motivation even under adverse conditions. Hope, in this sense, is not passive; it fosters agency and encourages constructive engagement.

When applied to eco-anxiety, hope functions as a vital counterbalance to despair. Climate-related distress can easily evolve into hopelessness, especially when individuals perceive environmental problems as overwhelming and systemic. Bury et al. (2020) emphasize that hope can serve as a psychological antidote to paralysis by despair. Importantly, hope does not minimize the seriousness of climate change. Instead, it provides the emotional stamina required to remain involved in long-term environmental action.

Marlon et al. (2019) further note that hope supports continued engagement with climate issues. Without hope, individuals may disengage, deny, or emotionally shut down. With hope, however, they are more likely to participate in collective solutions, advocate for change, and adopt sustainable behaviors. Hope supplies both perspective and energy; it reframes climate action as meaningful rather than futile.

Public speakers such as Lyn Stoler, in her TEDxManhattanBeach talk, offer deeply reflective insights into the psychological dimensions of climate distress. Her perspective underscores that acknowledging climate fear does not negate hope; rather, it can coexist with it. Betrò (2024) similarly suggests that hope enables individuals to accept the gravity of environmental threats while maintaining belief in the possibility of meaningful change. This dual awareness (realism combined with commitment) can help clients channel eco-anxiety into purposeful environmental protection and restoration efforts.

Active Hope (A Practical Framework):

A particularly influential framework for transforming eco-anxiety into constructive engagement is the concept of active hope. Introduced by Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone (2012) in their book Active Hope, this approach reframes hope as something we practice rather than something we passively possess.

Macy and Johnstone (2012) define active hope as acknowledging the reality of global challenges, envisioning the future we wish to create, and taking deliberate steps toward that future. As they state, “it is something we do rather than something we have” (p. 3). This definition highlights hope as an intentional process grounded in action and participation.

Active hope consists of three interconnected elements:

- Facing reality with mindfulness – Clients are encouraged to acknowledge climate change honestly without denial or avoidance. Mindfulness practices can help them remain present with difficult emotions without becoming overwhelmed.

- Envisioning desired outcomes – Rather than focusing solely on catastrophic predictions, individuals are invited to imagine the kind of world they wish to help build. This future-oriented vision nurtures meaning and direction.

- Taking purposeful action – Even small, values-based steps (such as community engagement, sustainable lifestyle adjustments, or advocacy) can restore a sense of agency.

Through this framework, eco-anxiety shifts from paralyzing fear to meaningful engagement. Active hope blends resilience, emotional awareness, and committed action. It does not promise guaranteed outcomes, nor does it ignore uncertainty. Instead, it encourages individuals to “show up” for the work of environmental care even when results are uncertain and agency feels limited.

Renée Lertzman contributes to this conversation in her TED talk, “How to Turn Climate Anxiety Into Action.” She explores how emotional responses to climate change (such as fear, grief, and avoidance) are natural human reactions. Drawing from psychological insights, she emphasizes creativity, relational connection, and emotional processing as pathways toward sustainable engagement. Her perspective reinforces the idea that action emerges not from suppressing anxiety, but from working compassionately with it.

So, hope is not the opposite of realism; it is the companion of resilience. In the context of eco-anxiety, hope provides emotional regulation, motivation, and direction. Through frameworks such as active hope, clinicians can guide clients toward acknowledging environmental realities while cultivating agency and constructive participation. By reframing eco-anxiety as a source of meaningful engagement rather than paralysis, hope becomes a powerful catalyst for psychological wellbeing and environmental action.

5 Promising Research-Based Coping Strategies:

While the drivers of eco-anxiety (such as climate change, political inaction, and environmental degradation) may feel vast and beyond individual control, psychological research reminds us that our internal responses remain adaptable. Ágoston et al. (2022) emphasize that although we cannot always change external realities, we can shape how we interpret and respond to them. Developing intentional coping strategies can reduce emotional overwhelm, restore agency, and strengthen resilience in the face of environmental uncertainty. Below are five evidence-based strategies that can support clients experiencing eco-anxiety.

- Build Inner Resilience Through Mindfulness and Self-Care: Mindfulness-based practices have been widely shown to enhance emotional regulation and stress tolerance. Techniques such as meditation, breathwork, compassionate self-reflection, mindful movement (e.g., yoga or walking meditation), and journaling can help clients observe their climate-related fears without becoming consumed by them (Pérez-Aranda et al., 2021).

Mindfulness fosters present-moment awareness, which can counteract the anticipatory anxiety often associated with eco-distress. Rather than spiraling into catastrophic future scenarios, clients learn to anchor themselves in what is happening now. Self-compassion practices are particularly important, as they help reduce eco-guilt and perfectionism by encouraging kindness toward oneself in the face of global challenges.

Consistent self-care (adequate sleep, balanced routines, emotional check-ins) also provides the psychological stamina needed to remain engaged with climate concerns without burnout.

- Proactive Environmental Action: Taking meaningful, values-aligned action can significantly reduce feelings of helplessness. Tingley (2023) highlights that proactive environmental behaviors (such as reducing personal carbon footprints, supporting sustainability initiatives, participating in local clean-up efforts, or advocating for policy change) can restore a sense of agency.

When individuals perceive that their actions matter, even in small ways, their emotional response shifts from paralysis to empowerment. Proactive engagement reframes eco-anxiety as a motivational signal rather than a debilitating force. Importantly, clinicians can help clients focus on sustainable, manageable actions rather than perfectionistic standards that may increase stress.

- Cultivate Supportive Connections: Social connection plays a powerful role in buffering stress. Turğut and Öztürk (2024) emphasize that joining environmental groups, climate support circles, or community-based sustainability projects can provide emotional validation and collective resilience.

Sharing concerns with others who understand climate distress reduces isolation and normalizes emotional reactions. Community engagement also reinforces the idea that climate action is not an individual burden but a collective effort. This sense of belonging and shared purpose can significantly reduce anxiety while increasing motivation and hope.

- Connect With Nature: Parreira and Mouro (2023) highlight the restorative benefits of spending time in natural environments. Regular exposure to green spaces (such as parks, forests, riversides, or gardens) can reduce stress, improve mood, and enhance overall wellbeing.

Ironically, while environmental degradation can be a source of anxiety, connection with nature can also be a source of healing. Direct engagement with natural environments often strengthens emotional bonds with the planet, which may inspire constructive environmental action rather than avoidance. Time in nature can foster gratitude, perspective, and a sense of interconnectedness that supports resilience.

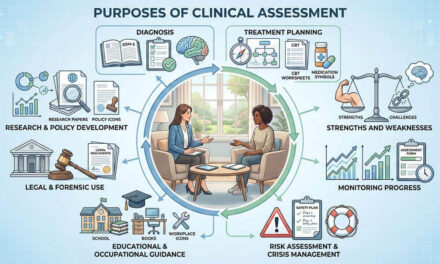

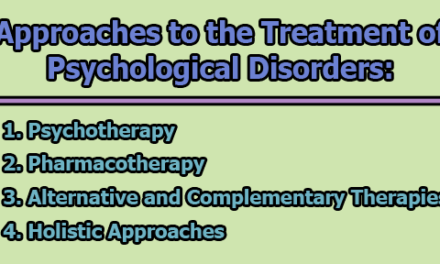

- Therapeutic Interventions: Structured psychological support can be particularly valuable for clients experiencing intense eco-anxiety. Ikiz and Carlson (2025) note that evidence-based therapeutic approaches (such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), grief counseling, art-based therapies, and group support interventions) can help individuals process complex climate-related emotions.

- CBT may assist clients in identifying and challenging catastrophic thinking patterns.

- ACT can help them accept difficult emotions while committing to values-driven action.

- Grief counseling addresses climate-related mourning and anticipatory loss.

- Art-based therapies provide nonverbal pathways for expressing fear, sadness, and hope.

- Support groups create safe spaces for shared reflection and empowerment.

Therapeutic work can reframe eco-anxiety as an understandable response to environmental realities, guiding clients toward meaning-making rather than avoidance.

Thus, although the causes of eco-anxiety may feel immovable, research shows that individuals can cultivate adaptive coping responses. Through mindfulness, proactive engagement, social connection, nature immersion, and structured therapeutic support, clients can transform environmental distress into resilience and purposeful action. These strategies do not eliminate the climate crisis—but they empower individuals to meet it with psychological strength, clarity, and hope.

How Positive Psychology Can Help With Climate Distress:

Positive psychology offers a constructive and empowering framework for addressing eco-anxiety. Rather than focusing solely on pathology or symptom reduction, positive psychology emphasizes strengths, gratitude, meaning, resilience, and wellbeing (Seligman, 2010). In the context of climate distress, this approach shifts attention from fear and helplessness toward growth and purposeful engagement. Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al. (2024) suggest that positive psychology provides an optimistic yet realistic lens through which individuals can reinterpret eco-anxiety; not as a weakness, but as a signal of care and commitment.

Importantly, positive psychology does not deny the seriousness of the climate crisis. Instead, it acknowledges the reality of environmental threats while encouraging adaptive responses. Eco-anxiety frequently arises from a perceived loss of control in the face of vast global challenges (Rehling, 2022). Climate change is often described as a wicked problem; a term introduced by Rittel and Webber (1974) to describe complex social and policy issues characterized by incomplete, contradictory, and evolving requirements. Wicked problems lack simple solutions, making them inherently frustrating and destabilizing.

This complexity can intensify feelings of powerlessness. When individuals perceive that the scale of climate change far exceeds their personal capacity to influence it, anxiety and despair can emerge. Positive psychology addresses this imbalance by creating space for agency and intentional action. Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al. (2024) highlight that even small, consistent pro-environmental behaviors (such as reducing waste, supporting sustainable initiatives, or participating in local environmental projects) can restore a sense of control and purpose. These actions reinforce the idea that while no single individual can solve climate change alone, meaningful contribution is still possible.

- Strengths and Meaning-Making: A core pillar of positive psychology involves identifying and applying personal strengths. Clients can be guided to reflect on qualities such as perseverance, compassion, creativity, or leadership and explore how these strengths might be directed toward environmental engagement. This strengths-based perspective fosters empowerment rather than paralysis.

Meaning-making is another central component. Baudon and Jachens (2021) suggest that reframing eco-anxiety as evidence of deep care for the planet can transform distress into purpose. Instead of interpreting anxiety as a sign of fragility, clients can view it as an expression of moral concern and ecological commitment. This shift in narrative helps integrate climate awareness into a broader sense of identity and values.

Practices such as mindfulness, compassion cultivation, and resilience training further support emotional regulation. These tools help individuals tolerate uncertainty and remain engaged without becoming overwhelmed. In this way, positive psychology strengthens both internal coping capacity and external action orientation.

- The Role of Social Connection: Positive psychology also emphasizes the importance of relationships and social belonging in promoting wellbeing (Hodges & Gore, 2019). Climate anxiety often intensifies in isolation, particularly when individuals feel that others do not share or validate their concerns. By engaging in environmental groups, sustainability initiatives, or climate dialogue circles, clients can shift from solitary distress to collective empowerment (Baudon & Jachens, 2021).

Social connection provides validation, shared purpose, and emotional support. Collective engagement reframes climate action as a communal effort rather than an individual burden. This sense of belonging not only reduces anxiety but also enhances motivation and resilience.

Consequently, positive psychology reframes eco-anxiety from a paralyzing condition into a potential catalyst for growth. By cultivating strengths, fostering meaning, encouraging small but meaningful action, and strengthening social connection, individuals can transform climate distress into resilience and constructive engagement. Rather than eliminating anxiety entirely, this approach integrates it into a broader narrative of purpose, connection, and commitment to building a more sustainable future.

In conclusion, Eco-anxiety is not a sign of fragility or irrationality; it is a psychologically coherent and morally grounded response to the realities of climate change. As research increasingly affirms, climate distress reflects an awareness of genuine ecological threats rather than exaggerated fear (Boluda-Verdú et al., 2022; Pihkala, 2020). For many clients, the intensity of eco-anxiety mirrors the depth of their care for the planet, future generations, and the integrity of natural systems. Recognizing this can reduce shame and self-criticism while reframing distress as evidence of empathy and ethical engagement.

At the same time, without supportive frameworks, eco-anxiety can become overwhelming; especially given the scale and complexity of climate change as a “wicked problem” (Rittel & Webber, 1974). Positive psychology offers an important counterbalance by encouraging individuals to cultivate strengths, resilience, and meaning (Seligman, 2010; Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2024). Rather than minimizing the crisis, this approach fosters agency through small, constructive actions and values-driven engagement.

Hope plays a particularly central role in this transformation. As Murphy (2023) and Ciarrochi et al. (2015) suggest, hope is not passive optimism but a dynamic psychological resource that sustains motivation and emotional regulation. The practice of active hope, as described by Macy and Johnstone (2012), provides a grounded framework for acknowledging reality while intentionally participating in change. Through mindfulness, resilience-building, and purposeful action, clients can shift from paralysis toward meaningful engagement (Baudon & Jachens, 2021).

Ultimately, the antidote to eco-anxiety is not denial or disengagement. It is connection; connection to oneself through emotional awareness, connection to supportive communities, and connection to the Earth through restorative engagement. When climate distress is met with compassion, collective action, and active hope, it can become not only manageable but transformative. In this way, eco-anxiety may serve as a catalyst for deeper commitment, shared resilience, and sustained efforts toward a more sustainable and life-affirming future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is eco-anxiety?

Eco-anxiety is a form of emotional distress related to concerns about climate change and environmental degradation. It can include fear, sadness, anger, guilt, and worry about the future of the planet. It is not considered a mental disorder, but it is increasingly recognized as a valid psychological response to real environmental threats.

Is eco-anxiety the same as general anxiety?

No, while eco-anxiety shares symptoms like worry and restlessness, it is specifically triggered by environmental concerns. It often includes moral, existential, and future-oriented dimensions that distinguish it from general anxiety.

Why are more people experiencing eco-anxiety today?

Increased media coverage, scientific reports, personal experiences of climate disasters, and perceived political inaction have made climate change feel more immediate and personal. Social media exposure and global awareness also amplify the emotional impact.

How can positive psychology help with eco-anxiety?

Positive psychology focuses on strengths, resilience, meaning, gratitude, and constructive action. Instead of denying climate concerns, it helps individuals channel their distress into purposeful engagement, personal growth, and sustainable coping strategies.

What is “active hope”?

Active hope is the practice of acknowledging environmental challenges while intentionally taking steps toward positive change. It involves facing reality, envisioning a better future, and engaging in meaningful action rather than waiting passively for solutions.

Can eco-anxiety be beneficial?

Yes, in moderate levels. Eco-anxiety can signal deep care for the environment and motivate positive change. When managed effectively, it can lead to pro-environmental behaviors, community engagement, and personal growth.

What practical coping strategies can reduce eco-anxiety?

Helpful strategies include:

- Mindfulness and emotional regulation practices

- Limiting excessive media consumption

- Spending time in nature

- Joining supportive environmental communities

- Taking small, manageable pro-environmental actions

- Seeking professional therapeutic support when needed

How can I prevent burnout while staying engaged in climate action?

Balance action with self-care. Set realistic goals, share responsibilities within a community, schedule breaks from climate-related content, and focus on what is within your control. Sustainable activism requires sustainable wellbeing.

Should therapists treat eco-anxiety differently from other anxieties?

Therapists should validate eco-anxiety as a rational response to real-world issues. While standard therapeutic approaches like CBT or ACT can help, incorporating meaning-making, values exploration, and community engagement can be especially beneficial.

What is the key message for managing eco-anxiety?

The goal is not to eliminate concern for the planet, but to transform distress into resilience and constructive action. Through connection, hope, and purposeful engagement, eco-anxiety can become a catalyst for growth rather than a source of paralysis.

References:

- Ágoston, C., Csaba, B., Nagy, B., Kőváry, Z., Dúll, A., Rácz, J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2022). Identifying types of eco-anxiety, eco-guilt, eco-grief, and eco-coping in a climate-sensitive population: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042461

- Banwell, N., & Eggert, N. (2023). Rethinking ecoanxiety through environmental moral distress: An ethics reflection. The Journal of Climate Change and Health 15, Article 100283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2023.100283

- Baudon, P., & Jachens, L. (2021). A scoping review of interventions for the treatment of eco-anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189636

- Betrò, S. (2024). From eco-anxiety to eco-hope: Surviving the climate change threat. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1429571

- Boluda-Verdú, I., Senent-Valero, M., Casas-Escolano, M., Matijasevich, A., & Pastor-Valero, M. (2022). Fear for the future: Eco-anxiety and health implications, a systematic review. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 84, Article 101904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101904

- Boyd, C., Jamieson, J., Gibson, K., Duffy, M., Williamson, M., & Parr, H. (2024). Eco‐anxiety among regional Australian youth with mental health problems: A qualitative study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 18(12), 1022–1031. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.13549

- Brophy, H., Olson, J., & Paul, P. (2022). Eco-anxiety in youth: An integrative literature review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 32(3), 633–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13099

- Bury, S., Wenzel, M., & Woodyatt, L. (2020). Against the odds: Hope as an antecedent of support for climate change action. British Journal of Social Psychology, e12343.

- Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P., Kashdan, T., Heaven, P., & Barkus, E. (2015). Hope and emotional well-being: A six-year study to distinguish antecedents, correlates, and consequences. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(6), 520–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1015154

- Coffey, Y., Bhullar, N., Durkin, J., Islam, S., & Usher, K. (2021). Understanding eco-anxiety: A systematic scoping review of current literature and identified knowledge gaps. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 3, Article 100047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100047

- Cosh, S., Ryan, R., Fallander, K., Robinson, K., Tognela, J., Tully, P., & Lykins, A. (2024). The relationship between climate change and mental health: A systematic review of the association between eco-anxiety, psychological distress, and symptoms of major affective disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 24, Article 833. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-06274-1

- Cunsolo, A., & Ellis, N. (2018). Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nature Climate Change, 8, 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2

- Hickman, C. (2020). We need to (find a way to) talk about … eco-anxiety. Journal of Social Work Practice, 34(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2020.1844166

- Hodges, J. M., & Gore, J. S. (2019). Social connections and well-being: With whom do you identify and why? Psychological Studies, 64(4), 436–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-019-00506-1

- Hogg, T., Stanley, S., O’Brien, L., Wilson, M., & Watsford, C. (2021). The Hogg eco-anxiety scale: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Global Environmental Change, 71, Article 102391. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/rxudb

- Ikiz, B., & Carlson, J. (2025). Neural pathways to resilience: Leveraging neuroscience to understand and mitigate eco‐anxiety. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1547, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.15347

- Jalin, H., Sapin, A., Macherey, A., Boudoukha, A., & Congard, A. (2024). Understanding eco-anxiety: Exploring relationships with environmental trait affects, connectedness to nature, depression, anxiety, and media exposure. Current Psychology, 43, 23455–23468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06098-y

- Jarrett, J., Gauthier, S., Baden, D., Ainsworth, B., & Dorey, L. (2024). Eco-anxiety and climate-anxiety linked to indirect exposure: A scoping review of empirical research. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 96, Article 102326, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2024.102326

- Kankawale, S., & Niedzwiedz, C. (2023). Eco-anxiety among children and young people: Systematic review of social, political, and geographical determinants. MedRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.12.19.23300198v2

- Liu, J., Shi, Y., Xie, S., Xing, L., Wang, L., Li, W., & Zhao, X. (2025). Meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal cohort studies on the impact of childhood traumas on anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 374, 443–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2025.01.067

- Macy, J., & Johnstone, C. (2012). Active hope: How to face the mess we’re in without going crazy. New World Library. https://www.activehope.info/the-book

- Makeda, K. (2024). The psychological effects of environmental degradation on human well-being. International Journal of Humanity and Social Sciences, 2(5), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.47941/ijhss.1886

- Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Léger-Goodes, T., Herba, C., Bélanger, N., Smith, J., & Marks, E. (2024). Meaning making and fostering radical hope: Applying positive psychology to eco-anxiety research in youth. Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frcha.2024.1296446

- Marlon, J., Bloodhart, B., Ballew, M., Rolfe-Redding, J., Roser-Renouf, C., Leiserowitz, A., & Maibach, E. (2019). How hope and doubt affect climate change mobilization. Frontiers in Communication, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2019.00020

- Murphy, E. (2023). Hope and well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 50, Article 101558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101558

- Niedzwiedz, C., & Katikireddi, S. (2023). Determinants of eco-anxiety: Cross-national study of 52,219 participants from 25 European countries. European Journal of Public Health, 33, Supplement 2. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckad160.069

- Orrù, L., Taccini, F., & Mannarini, S. (2024). Worry about the future in the climate change emergency: A mediation analysis of the role of eco-anxiety and emotion regulation. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030255

- Parreira, N., & Mouro, C. (2023). Living by the sea: Place attachment, coastal risk perception, and eco-anxiety when coping with climate change. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1155635

- Pérez-Aranda, A., García-Campayo, J., Gudé, F., Luciano, J., Feliu‐Soler, A., González-Quintela, A., López-Del-Hoyo, Y., & Montero-Marín, J. (2021). Impact of mindfulness and self-compassion on anxiety and depression: The mediating role of resilience. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 21(2), Article 100229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2021.100229

- Pihkala, P. (2020). Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability, 12(19), 7836. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12197836

- Pihkala, P. (2022). The process of eco-anxiety and ecological grief: A narrative review and a new proposal. Sustainability, 14(24), 16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416628

- Rehling, J. (2022). Conceptualising eco-anxiety using an existential framework. South African Journal of Psychology, 52(4), 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/00812463221130898

- Renna, M., O’Toole, M., Spaeth, P., Lekander, M., & Mennin, D. (2018). The association between anxiety, traumatic stress, and obsessive–compulsive disorders and chronic inflammation: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 35, 1081–1094. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22790

- Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1974). Wicked problems. Man-Made Futures, 26(1).

- Seligman, M. (2010). Flourish: Positive psychology and positive interventions. The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, 31(4), 1–56. 272–280.

- Shao, L., & Yu, G. (2023). Media coverage of climate change, eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior: Experimental evidence and the resilience paradox. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 91, Article 102130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102130

- Sims, L., Rocque, R., & Desmarais, M. (2020). Enabling students to face the environmental crisis and climate change with resilience: Inclusive environmental and sustainability education approaches and strategies for coping with eco-anxiety. International Journal of Higher Education and Sustainability, 3(2), 112–131 https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHES.2020.10035343

- Tingley, J. (2023). Exploring a momentary eco-anxiety induction technique using a mixed-methods approach. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.22215/etd/2023-15682

- Turğut, F., & Öztürk, M. (2024). Interventions for the treatment of eco-anxiety. Current Approaches in Psychiatry, 17(2), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.18863/pgy.1508265

- Usher, K., Durkin, J., & Bhullar, N. (2019). Eco-anxiety: How thinking about climate change-related environmental decline is affecting our mental health. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(6), 1233–1234. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12673

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College