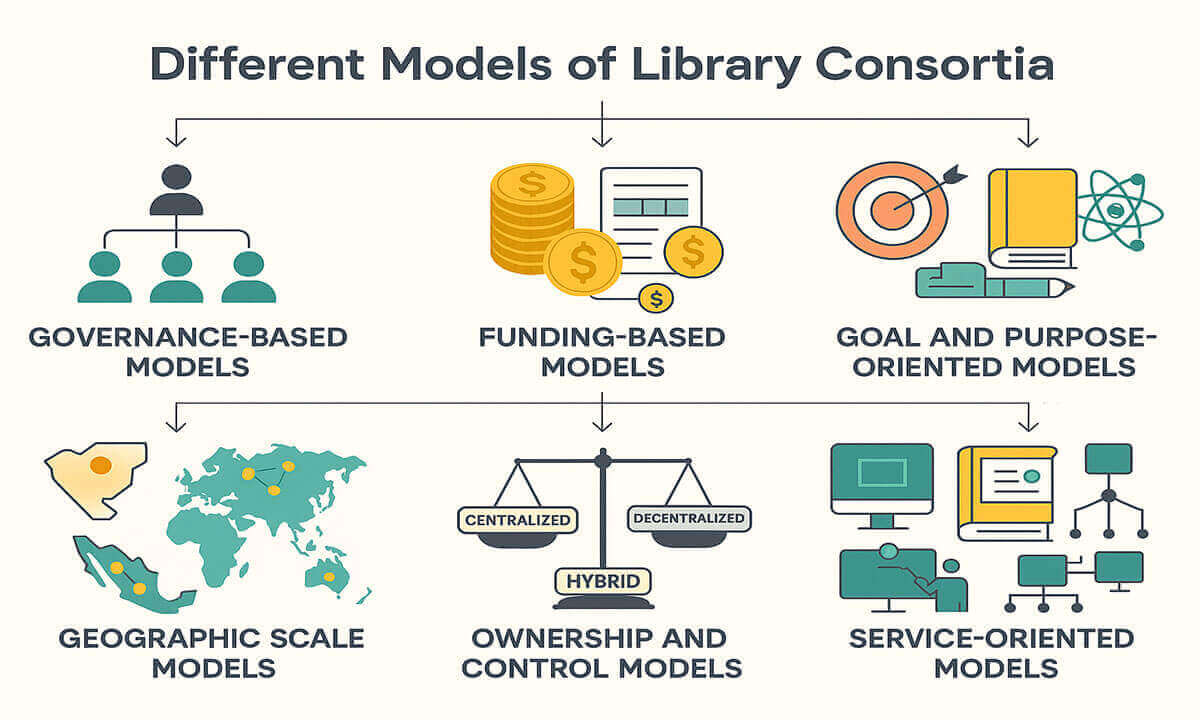

Different Models of Library Consortia:

Library consortia have become essential collaborative frameworks in the modern information age. With the exponential growth of digital resources and rising subscription costs, libraries worldwide face increasing pressure to deliver high-quality resources while staying within limited budgets. Consortia address these challenges by pooling resources, negotiating collectively with publishers, and creating platforms for cooperation. Over the years, different models of library consortia have emerged, each shaped by governance, funding structures, goals, geographic scope, ownership patterns, and services offered. Understanding these models is important because they reveal not only how libraries collaborate but also how such partnerships can be sustained in diverse contexts.

1. Governance-Based Models of Library Consortia: The governance structure of a library consortium determines how decisions are made, how responsibilities are distributed among member institutions, and how collective goals are pursued. Governance is not only a matter of organizational formality but also a critical factor that influences the effectiveness, sustainability, and credibility of the consortium. Well-designed governance ensures that all participating libraries feel represented and that resources are managed transparently.

In many cases, library consortia adopt a committee-based governance system. In this model, representatives from each member institution are elected or nominated to form a governing board or council. This board is responsible for setting policies, negotiating with publishers, monitoring resource usage, and resolving disputes. The advantage of this approach is that it promotes inclusivity and equal participation, giving smaller institutions a voice alongside larger, resource-rich universities. For example, in several national consortia in Asia and Europe, governance boards are composed of academic librarians, IT experts, and senior administrators who together ensure that different perspectives are integrated into decision-making.

Another form of governance is the centralized model, where authority is concentrated in a lead institution or a government agency. Here, the central body takes responsibility for negotiating licenses, allocating funds, and maintaining digital infrastructure. This model often works well in countries where government funding supports national-level consortia, such as in India through initiatives under the INFLIBNET Centre. The centralized approach provides efficiency and speed in decision-making, but it may sometimes limit the autonomy of individual member libraries.

On the other hand, decentralized governance structures allow each participating library to retain significant independence. In this model, consortia act more as facilitators of cooperation rather than as controlling authorities. Libraries decide individually on resource acquisition while joining forces for activities like training workshops, cataloguing systems, or document delivery networks. This model tends to foster innovation and flexibility, but it can also create challenges in achieving collective bargaining power if members are not aligned in their goals.

A more recent development is the hybrid governance model, which combines centralized oversight with participatory mechanisms. For instance, a central body may negotiate contracts with publishers and maintain digital infrastructure, while member libraries have committees to discuss local implementation, training needs, or evaluation of resource usage. This blended approach ensures both efficiency and inclusiveness, balancing the benefits of centralized authority with the need for member participation.

Governance models also vary according to the legal and administrative frameworks within which consortia operate. Some are formally registered as non-profit organizations, which allows them to sign contracts and manage funds independently. Others exist as informal associations of libraries, relying on mutual agreements and shared responsibilities. Formal legal status can strengthen accountability, whereas informal structures may reduce bureaucratic complexity and allow for quicker adjustments to new challenges.

Eventually, governance is the backbone of any consortium. Without clear decision-making processes, accountability, and mechanisms for representation, even well-funded or technologically advanced consortia may struggle to sustain themselves. Effective governance requires transparency, equitable participation, and adaptability. By ensuring that members feel ownership of the consortium’s decisions and policies, governance structures lay the foundation for long-term collaboration and trust.

2. Funding-Based Models of Library Consortia: Funding is one of the most decisive elements that shape the structure and long-term sustainability of a library consortium. No matter how well-designed the governance system is, a consortium cannot thrive without a reliable financial model to support the acquisition of resources, development of infrastructure, and delivery of services. Different funding strategies have emerged worldwide, reflecting the economic realities, policy environments, and institutional capacities of participating libraries.

One of the most common approaches is the centrally funded model, where a government agency or a national educational body provides financial support. In this arrangement, libraries do not contribute directly to subscription costs, which makes it highly inclusive and particularly beneficial for smaller or resource-poor institutions. For example, in Bangladesh, the UGC Digital Library is fully supported by the University Grants Commission, which negotiates with international publishers and provides access to electronic journals and databases for public universities. Similarly, in India, consortia under the INFLIBNET Centre, such as the UGC-INFONET and INDEST-AICTE Consortia, rely heavily on government funding to ensure equitable access across universities. The strength of this model is that it reduces financial inequality among institutions. However, its sustainability depends heavily on political and economic stability, since any reduction in government support can disrupt access for all members.

Another widely used model is the shared budget model, where costs are divided among participating libraries. This contribution may be equal for all members, or it may be proportional based on specific factors such as student enrollment, institutional budget, or actual resource usage. Equal contribution models encourage a sense of fairness but may place a heavier burden on smaller institutions. Proportional contribution models, on the other hand, are considered more equitable because they account for differences in institutional capacity, though they require sophisticated systems for monitoring usage and adjusting payments. Shared budget models also encourage libraries to be more engaged in decision-making since they are directly investing their own funds.

A third approach is the hybrid funding model, which combines central government support with member contributions. For instance, a government may cover the core subscription costs of essential databases, while member libraries contribute additional funds to access specialized subject resources or premium services. This model provides a balance between inclusivity and financial sustainability. It also ensures that members take ownership of the consortium while still benefiting from national-level subsidies. Hybrid models are becoming increasingly common in many developing countries where governments recognize the importance of supporting education but also encourage institutions to share responsibility.

In some cases, consortia are self-funded, relying entirely on contributions from member institutions without government support. These models are usually seen in regional or local consortia, especially in countries where national-level support is unavailable. Although self-funded models encourage strong collaboration and independence, they may struggle to include smaller institutions with limited budgets. Over time, this can lead to inequality within the consortium if wealthier institutions dominate resource access and decision-making.

Subsequently, there are vendor-driven funding arrangements, where publishers or commercial providers initiate the consortium and set pricing models for groups of libraries. While these arrangements can provide immediate access to resources at discounted rates, they may limit the bargaining power of libraries, as the structure is influenced heavily by the commercial interests of vendors.

The choice of funding model is not only a financial decision but also a reflection of the values and priorities of the consortium. Centrally funded and hybrid models emphasize inclusivity and national development, while shared and self-funded models highlight autonomy and responsibility. A sustainable funding framework ensures that resources are consistently available, costs are fairly distributed, and long-term collaboration is possible. Ultimately, successful consortia adapt their funding strategies to the changing economic environment, striking a balance between affordability, equity, and sustainability.

3. Goal and Purpose-Oriented Models of Library Consortia: The goals and purposes behind the formation of a library consortium strongly influence its structure, membership policies, and the types of services it delivers. While financial efficiency and shared access to resources remain central to all consortia, many are built with additional objectives that reflect the academic, cultural, or technological needs of their members. These goal-oriented distinctions give rise to different models of collaboration that can vary significantly in focus and scope.

One common type is the open membership consortium, which allows any eligible institution to join voluntarily. This model emphasizes inclusivity and flexibility, enabling universities, research centers, and even smaller colleges to become part of the network. Open membership encourages wider collaboration, strengthens collective bargaining, and creates opportunities for knowledge sharing across diverse institutions. However, it can also present challenges in governance, as the wide variation in member size and capacity may lead to unequal levels of participation.

In contrast, a closed membership consortium restricts participation to specific institutions, often based on criteria such as government approval, geographic boundaries, or academic specialization. National consortia formed by higher education authorities often follow this approach, ensuring that only recognized institutions are part of the network. For example, consortia led by government education commissions usually restrict membership to accredited public universities. This model promotes stronger cohesion and simplifies management but can exclude independent or private institutions that might also benefit from shared resources.

Another important form is the publisher-initiated consortium, where resource providers take the lead in organizing groups of libraries under special pricing or subscription models. Publishers may offer discounts or package deals if multiple libraries join together, reducing costs for participants while expanding the publisher’s customer base. While this model can be financially advantageous in the short term, it often raises concerns about autonomy, as the consortium’s structure is largely shaped by commercial interests rather than by the shared goals of libraries.

Consortia can also be discipline-specific, focusing on a particular field of study such as medicine, engineering, or law. These specialized consortia emerge when institutions with strong research or teaching needs in a certain area collaborate to secure access to subject-relevant journals, databases, and e-books. For instance, medical library consortia often negotiate for access to clinical databases, biomedical journals, and evidence-based practice tools. This targeted approach ensures that member libraries receive resources closely aligned with their academic mission, but it may limit participation to institutions with similar subject priorities.

Beyond resource sharing, some consortia are formed with the purpose of infrastructure development and professional capacity-building. Such consortia may invest in shared cataloguing systems, interlibrary loan networks, or digital repositories that support long-term preservation of scholarly work. They may also organize training workshops, conferences, and exchange programs to enhance the professional skills of librarians and information specialists. In these models, the purpose extends beyond saving costs to building a stronger collective knowledge ecosystem.

The diversity of goal-oriented consortia highlights that collaboration is not only about acquiring materials at reduced prices but also about aligning libraries with broader academic and societal objectives. Whether the aim is inclusivity, exclusivity, specialization, or professional development, the stated goals shape the identity of the consortium, guide its governance structure, and influence its long-term sustainability.

4. Geographic Scale Models of Library Consortia: Another important way to classify library consortia is by their geographic scope. The scale of operation often determines the resources available, the services offered, and the extent of influence a consortium can achieve in negotiations with publishers or in setting professional standards. Geographic scale models range from small, localized networks to large international collaborations, each with its own strengths and limitations.

At the most immediate level are local consortia, which are formed within a single university system, city, or cluster of neighboring institutions. Their focus is typically on practical resource sharing such as interlibrary loans, cooperative cataloguing, and joint training programs for staff. Because of their small size and proximity, local consortia are relatively easy to manage and can adapt quickly to the specific needs of their members. For instance, a group of colleges in one city may create a shared digital repository or establish a common borrowing system that expands the resources available to all students. The limitation of local consortia, however, is that their bargaining power with publishers remains relatively weak due to the small scale of participation.

Expanding outward, regional consortia bring together institutions from a wider area, such as a province, a state, or even a large metropolitan region. These consortia are more capable of negotiating with vendors and may have greater resources to invest in joint infrastructure projects. In India, examples like ADINET (Ahmedabad Library Network) and MALIBNET (Madras Library Network) demonstrate how regional collaborations can strengthen interlibrary lending, create shared union catalogues, and provide professional training. Regional consortia often serve as stepping stones for the development of national-level initiatives, proving that cooperation at the regional level can inspire larger movements.

At the national level, consortia play a strategic role in shaping the higher education and research landscape of entire countries. INFLIBNET’s UGC-INFONET and INDEST consortia in India or the UGC Digital Library in Bangladesh are prime examples of national consortia that have expanded access to thousands of journals, e-books, and databases across public universities. National consortia benefit from government support and policy backing, which not only makes them financially sustainable but also ensures equity of access across institutions of varying capacities. Their bargaining power with publishers is also considerably stronger than that of smaller networks, often securing discounts and access terms that individual libraries could not obtain on their own.

Finally, at the broadest level, there are international consortia, which bring together libraries from multiple countries. Global collaborations such as the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) and the International Coalition of Library Consortia (ICOLC) demonstrate how institutions can transcend national boundaries to share resources, establish standards, and build global catalogues. These consortia are particularly valuable for promoting cross-border research, facilitating interlibrary loans at the global scale, and encouraging professional cooperation among librarians worldwide. Their reach also enhances their ability to influence publishers and vendors by representing an international user base. However, managing international consortia involves complexities such as varying copyright laws, linguistic diversity, and differences in technological infrastructure across countries.

The geographic scale of a consortium, therefore, has a profound impact on its identity and effectiveness. Local and regional consortia provide agility and close-knit collaboration, national consortia ensure equity and strong bargaining power, while international consortia extend cooperation to a global level. Each scale has unique benefits and challenges, but together they illustrate the rich variety of collaborative possibilities that enable libraries to enhance access, share knowledge, and support research more effectively.

5. Ownership and Control Models of Library Consortia: The ownership and control structure of a library consortium determines how authority, responsibilities, and decision-making powers are distributed among its members. While funding defines how resources are sustained and governance outlines how policies are created, ownership and control decide who has the final authority over the consortium’s operations, negotiations, and resource management. Different approaches to ownership create variations in how centralized or decentralized a consortium becomes, and each model carries its own advantages and challenges.

In a centralized ownership model, a single body or agency—often a government authority, national educational council, or lead institution—takes primary responsibility for managing the consortium. This includes negotiating with publishers, handling finances, maintaining digital infrastructure, and enforcing policies. The centralized approach ensures uniformity in decision-making, consistency in service delivery, and efficiency in managing contracts. For example, national consortia such as India’s INFLIBNET Centre operate under this model, with the government playing a dominant role in funding and management. The benefit of centralization lies in its streamlined structure, which minimizes duplication of effort. However, smaller member institutions may feel less empowered in decision-making, as most authority rests with the central body.

In contrast, decentralized ownership models distribute control more evenly among participating libraries. Here, each institution retains a significant degree of independence in decision-making while still collaborating with other members in certain areas such as cataloguing, training programs, or interlibrary loans. This model often works well in regional or subject-specific consortia where members share common goals but prefer to maintain autonomy over their budgets and resource choices. The advantage of decentralization is flexibility, as institutions can tailor their participation to their own needs. The downside, however, is that it may reduce the bargaining strength of the consortium as a whole, since members do not always present a unified front in negotiations with vendors.

A third approach is the hybrid ownership and control model, which combines centralized authority with participatory mechanisms. In this arrangement, a central body may handle core responsibilities such as contract negotiation and infrastructure management, while member institutions are given authority over certain aspects, such as selecting optional resources or designing training initiatives. Hybrid models attempt to balance efficiency with inclusivity, ensuring that libraries feel ownership while still benefiting from the strategic direction of a central authority. Many successful national and regional consortia today operate under hybrid arrangements because they accommodate diverse institutional needs.

Ownership also has a legal dimension. Some consortia are established as independent legal entities, registered as non-profit organizations or trusts. This gives them the capacity to sign contracts, receive funds, and manage assets directly. Legal independence strengthens accountability and ensures transparency, as the consortium is treated as a separate institution rather than as a program of a single university or government agency. Others exist as informal associations, relying on mutual agreements without legal incorporation. While informal structures reduce bureaucracy and allow flexibility, they may face limitations in areas such as contract enforcement or long-term financial planning.

Another factor influencing ownership is whether a consortium is vendor-driven or library-driven. In vendor-driven arrangements, commercial publishers may take the lead in shaping the structure of the consortium, offering resource bundles to groups of libraries. While this can provide immediate access at discounted rates, it limits the control libraries have over policies and long-term strategies. In library-driven models, on the other hand, member institutions maintain full ownership and control, ensuring that decisions align with academic and research priorities rather than commercial goals.

Therefore, ownership and control models highlight the pressure between efficiency and autonomy. Centralized ownership maximizes coordination and bargaining power, decentralized ownership fosters independence and flexibility, and hybrid ownership seeks to balance both. The choice of model depends on the political, financial, and academic environment in which the consortium operates. What matters most is that ownership structures create a sense of shared responsibility and trust among members, since this collective commitment is what sustains collaboration over time.

6. Service-Oriented Models of Library Consortia: While governance, funding, goals, geography, and ownership define the structure of a consortium, its true value is measured by the services it delivers to members. Service-oriented models emphasize the practical benefits of collaboration, focusing on how libraries can improve access to information, strengthen infrastructure, and enhance professional growth through collective efforts. These models vary widely depending on member needs, but they all share the objective of delivering tangible value to libraries and their users.

The most common service offered by consortia is collective licensing and resource sharing. By negotiating as a group, libraries can secure favorable pricing and access to electronic journals, e-books, and databases that would be prohibitively expensive individually. This service ensures wider access to scholarly materials, particularly for smaller institutions with limited budgets. For example, large national consortia often negotiate “big deals” with publishers, enabling even rural or less-funded universities to access high-quality research materials. Resource sharing also extends to interlibrary loans and document delivery services, where members lend physical or digital materials to one another, broadening the scope of resources available to users.

Another important service is the development of technological infrastructure. Many consortia invest in shared cataloguing systems, union databases, discovery tools, and digital repositories. Shared platforms reduce redundancy, standardize cataloguing practices, and make it easier for users to search across collections. The OCLC’s WorldCat, for instance, is a global catalogue built on consortium principles, enabling libraries worldwide to locate and share materials efficiently. Regional and national consortia also develop digital preservation systems to safeguard scholarly outputs, ensuring long-term access to knowledge.

Professional development and training represent another critical service area. Consortia often organize workshops, seminars, and online courses for librarians, helping them stay updated with new technologies, information management practices, and digital tools. These initiatives not only improve professional competence but also foster a sense of community among librarians. For smaller institutions, training programs provided through consortia are often the only opportunity for librarians to access specialized skills development.

Some consortia also pursue subject-based or discipline-specific services. For example, medical library consortia may focus on negotiating access to clinical databases, evidence-based resources, and biomedical journals, while engineering consortia might prioritize technical databases and patents. By tailoring services to the needs of specific academic disciplines, consortia ensure that the resources they provide are highly relevant to teaching and research priorities.

Additionally, consortia contribute to policy development and advocacy. By representing the collective interests of libraries, they can influence national policies on copyright, digital access, and open educational resources. International consortia, in particular, play an important role in setting global standards for metadata, cataloguing, and digital preservation, ensuring interoperability across systems and institutions.

In some contexts, service-oriented models extend beyond resource access to include collaborative research and innovation projects. Libraries working together under consortia may jointly develop software tools, contribute to open-source platforms, or conduct studies on user needs and information behavior. Such initiatives strengthen the innovation capacity of libraries and align them with broader research goals.

Ultimately, service-oriented models demonstrate that consortia are not only about saving costs but also about creating new opportunities for knowledge access, professional growth, and innovation. By prioritizing user needs and institutional development, these models ensure that collaboration leads to measurable improvements in library services. A strong service orientation also enhances the relevance of consortia, encouraging long-term commitment from members and ensuring that the benefits of cooperation are widely felt across academic and research communities.

In conclusion, Different models of library consortia demonstrate the diverse ways in which libraries collaborate to overcome financial, technological, and institutional challenges. Governance-based models ensure fairness and representation, while funding-based approaches secure sustainability. Goal-oriented structures align consortia with institutional missions, and geographic models highlight the varying scales of cooperation. Ownership and control patterns determine how power and responsibility are distributed, while service-oriented models show the practical benefits of collaboration. No single model is universally superior; rather, the success of a consortium depends on its ability to align with the needs, capacities, and contexts of its members.

As the information landscape continues to evolve, hybrid and flexible models are becoming increasingly common. By combining strengths from different approaches, consortia can remain resilient, relevant, and impactful. Ultimately, library consortia are more than cost-saving arrangements—they are engines of knowledge sharing, professional development, and equitable access, ensuring that libraries remain vital to education and research in the digital age.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is a library consortium?

A library consortium is a cooperative association of libraries that come together to share resources, negotiate with publishers collectively, and provide services that would be difficult or expensive to achieve individually. By collaborating, libraries can expand access to information, reduce costs, and strengthen their professional capacity.

Why are different models of library consortia needed?

Different models exist because libraries vary in size, funding capacity, academic focus, and geographic location. A model that works for a small regional group may not be suitable for a national or international network. Having diverse models allows libraries to collaborate in ways that best meet their unique needs and circumstances.

What is the difference between centralized and decentralized consortia?

In centralized consortia, a central body (such as a government agency or lead institution) manages resource acquisition, negotiations, and infrastructure. This ensures efficiency but may limit member autonomy. In decentralized consortia, each library retains independence and contributes to collaborative activities voluntarily, which provides flexibility but may reduce collective bargaining strength.

How are library consortia usually funded?

Funding can come from multiple sources. Some consortia are fully supported by government funding, ensuring inclusivity across public institutions. Others follow cost-sharing models where members contribute equally or proportionally based on size or usage. Hybrid models combine central funding with member contributions. A few are entirely self-funded or initiated by publishers.

What services do library consortia typically provide?

Consortia provide services such as collective subscription to electronic resources, interlibrary loan, union catalogues, digital repositories, training programs, and professional development opportunities. Some also specialize in discipline-specific resources (such as medicine or engineering), while others engage in advocacy and policy development.

What role do international consortia play?

International consortia, such as OCLC or ICOLC, extend collaboration beyond national borders. They promote global resource sharing, set international standards for cataloguing and metadata, and support cross-border research collaboration. They also strengthen the bargaining power of libraries by representing a large, international user base in negotiations with publishers.

Which model is the best for libraries?

There is no single best model. The effectiveness of a consortium depends on the goals of the member institutions, the availability of funding, and the geographic and political context. For example, government-funded national consortia work well in developing countries, while self-funded or regional consortia may be more suitable where autonomy and local needs are priorities.

How do consortia benefit students and researchers directly?

Students and researchers benefit by gaining access to a much wider range of academic resources than their home institution could afford alone. They also enjoy faster access to materials through interlibrary loans, better-trained library staff, and exposure to modern digital tools and platforms supported by consortia.

Library Lecturer at Nurul Amin Degree College